A Whole Health approach to skin health incorporates a variety of lifestyle practices (including diet, movement, and sleep), supplements, herbs, mind-body approaches, elements from health systems such as Chinese medicine and Ayurveda, along with conventional Western medicine. Evidence supporting the benefit of healing modalities that used to be considered “alternative” continues build. Patients and health care clinicians are looking for and finding that many of these practices can augment their journeys toward optimal health, and that includes skin health.

The Whole Health program emphasizes mindful awareness and Veteran self-care along with conventional and integrative approaches to health and well-being. The Circle of Health highlights eight areas of self-care: Surroundings; Personal Development; Food & Drink; Recharge; Family Friends, & Co-Workers; Spirit & Soul; Power of the Mind, and Moving the Body. The overview below shows what a Whole Health clinical visit could look like and how to apply the latest research on complementary and integrative health (CIH) to skin health.

Meet the Veteran

Amy is a 22-year-old female college student. Without any way to pay for further education, she started to work at a fast food chain after high school. Later, she enlisted in the GI bill and is now struggling to meet the demands of university classes. This has become increasingly more difficult for her due to an increased intensity of her eczema. As a young child, Amy had trouble with eczema. As she got older, it seemed to become less of a problem. She has had occasional flares—especially at the changes of seasons. In general, these flares have been mild compared to her childhood eczema. When she initiates treatment with topical steroids at the beginning of a flare, she is generally able to control it. She also suffers from seasonal allergies each spring, and has a strong family history of allergies, asthma, and hay fever.

A couple of months after starting classes at the university, Amy had a really bad flare of eczema that has not been easily controlled with her typical regimen of topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment twice a day for 1-2 weeks followed by hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment twice a day until the flare subsides). She usually takes long, hot showers which seem to temporarily ease the itching. Her use of moisturizers is spotty as she often is in a hurry once she gets out of the shower. She occasionally uses a small amount of lotion randomly throughout the day. Amy is particularly itchy at night. She finds herself distracted in classes which she attributes to the itching and to the lack of good quality sleep. She has been limiting her exercise because sweating stings the inflamed areas, and because she is really tired. She is beginning to wonder if she can pull off getting through college and fulfilling her dream of becoming an engineer and designing safer mobile military bases.

Personal Health Inventory

On her Personal Health Inventory (PHI), Amy rates herself a 2 out of 5 for her overall physical well-being and a 2 for overall mental and emotional well-being. When asked what matters most to her and why she wants to be healthy, Amy responds:

“I want to feel confident that I can make it through the demands of college and beyond. I want to feel proud of myself and to be a role model for young women in my community. I’d like to be both physically and mentally strong and to spend time with my friends and family.”

For the eight areas of self-care, Amy rates herself on where she is, and where she would like to be. Amy decides to first focus on the areas of Recharge and Food and Drink by getting more sleep, bringing her lunch to campus, and drinking more water.

For more information, refer to Amy’s PHI.

Introduction

Note: The terms atopic dermatitis and eczema are used interchangeably in this document and refer to chronically itchy and inflamed skin which may be accompanied by hay fever and/or asthma. This overview focuses primarily on eczema as one of the most common skin disorders, and a separate atopic dermatitis Whole Health tool is available for it, as are tools for psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, skin cancer, acne, and rosacea.

Atopic dermatitis, or eczema, is a chronic and relapsing dermatitis that typically shows up during infancy or early childhood. It affects 5%-20% of the childhood population around the world and appears eczema is becoming more common. The incidence in the United States is 11%. It is more prevalent in developed nations and has been found to be associated with higher household education levels, higher household income levels, smaller family size, urban location, and non-Caucasian ethnicity.[1] Eczema is grouped into three age categories: infantile, childhood, and adult. In infants, the face and extensors are typically involved. Childhood and adult eczema tend to affect the flexural areas and is characterized by chronic inflammation with dry, scaly, thickened skin. People with eczema typically have lowered thresholds for skin irritants. Heat and perspiration are the most common offenders, with wool and emotional stress close behind.

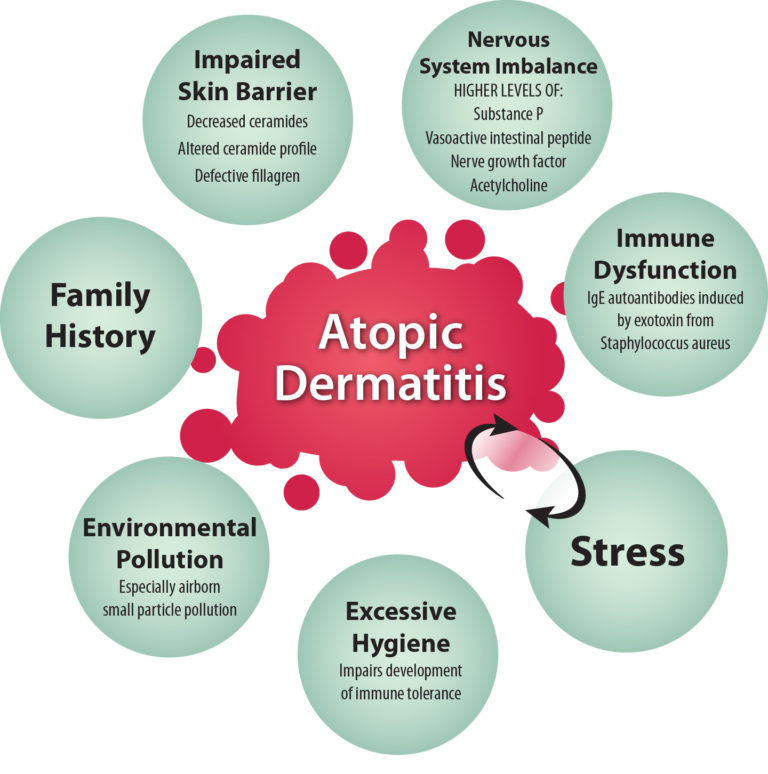

There are many factors at play in the development of eczema. Family history (especially maternal history) is a strong predictive risk factor, but there appear to be many environmental factors as well. The hygiene hypothesis was introduced in 1989 and postulates that exposure to microorganisms helps people develop stronger immune systems, and without this exposure, the development of immune tolerance is hindered. This has been supported by multiple studies including one that looks specifically at hygiene practices. It appears that more-frequent washing and the use of chemical household cleaners increases the risk of developing atopic dermatitis.[2] Environmental pollution—particularly aerosolized small particle pollutants such as pollution from traffic and factories—also appears to play a role in the development of eczema. In a study of 3,000 school children in West Germany the exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) was correlated with increased risk of eczema.[3] Similarly, a study of 5,000 children in different cities in France found a positive correlation with fine-particle pollution.[4]

Patients with eczema have identifiable immune dysfunction and are at a higher risk for developing viral infections of the skin, fungal infections of the skin, and increased colonization with staphylococcus aureus with potential secondary infection.[5] Exotoxins secreted from S. aureus have been found to act as classic antigens as well as superantigens inducing IgE specific antibodies that cross link with proteins in the skin. Concentrations of these IgE autoantibodies have been positively correlated with severity of atopic dermatitis.[6]

Patients with eczema have shown to have imbalances in the nervous system as well. They have higher levels of vasoactive intestinal peptide, nerve growth factor, and substance P—compounds involved in producing the sensation of itch and in IgE mediated sensitization to allergens.[7] The sensory hypersensitivity seen in patients with atopic dermatitis causes people with this condition to interpret light stimulation as itch rather than light touch.[8] This is significant because the act of scratching itself can lead to the release of substance P (which leads to release of histamine) and proinflammatory cytokines[9] which help to propagate the itch-scratch cycle so characteristic of this disorder.

Additionally, skin affected by eczema has been shown to have increased levels of acetylcholine.[10] Patients with eczema experience itching with exposure to acetylcholine while normal controls experience a burning sensation.[11] Additionally, one of the roles of acetylcholine is to activate sweat glands. Interestingly, people with eczema have a decreased ability to deliver sweat to the surface of the skin in response to heat when compared to normal controls, and a protein made and secreted by sweat glands can be found in the dermis of affected skin, suggesting that the abnormal sweat response may play a role in inducing inflammation in this condition.[12][13] This helps explain why heat and sweat are so irritating to people with eczema.

The skin barrier is also disturbed in patients with eczema. People with this condition have been shown to have increased trans-epidermal water loss and decreased ability to retain water in the epidermis.[14] Ceramides are fatty substances that make up a large part of cell membranes and play a significant role in maintaining hydration in the skin. The skin of people with eczema has been shown to have both decreased levels of total ceramides in the outer epidermis, but also an altered profile of the ceramides present.[15] More recently, fillagren—a protein important in maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier—has been found to be defective in the skin of people with atopic dermatitis as well as other conditions characterized by an impaired skin barrier.[16] Fillagren helps protect from environmental insults as well as water loss through the skin.[17]

Along with the physical symptoms of this condition, atopic dermatitis carries a significant emotional burden as well. There have been many studies looking at the effects atopic dermatitis has on quality of life and psychosocial status. It is clear that there are significant decreases in quality of life and self-esteem as well as increases in sleep disturbances, depression, and anxiety for both the patients and parents of patients with this condition.[18][19][20][21] The fact that stress worsens symptoms of atopic dermatitis can result in a downward spiral, with stress from the atopic dermatitis worsening the flare, which can worsen stress. Societal costs of eczema are also significant and include direct costs due to treatments and health care visits as well as indirect costs from lost days of work and disability claims.[22][23][24]

Conventional Approaches

Conventional therapy for eczema typically involves avoidance of irritants and allergens and good skin hydration practices. Topical immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids and tacrolimus/pimecrolimus are typically the mainstay of treatment for mild to moderate flares, while UV phototherapy and a combination of antihistamines can help minimize more significant flares. Appropriate use of antibiotics, either topical or systemic, is important when secondary infection is present. Very severe flares may warrant the use of systemic corticosteroids or other systemic immunosuppressive or biologic agents

Adequate skin hydration is the most basic aspect of care for both prevention of eczema flares and for treatment of active disease. This begins with minimizing contact with irritants—including hot water. Both frequency and duration of bathing should be limited, and the lowest water temperature tolerable to the patient should be used. Generous amounts of thick cream or ointment should be applied to the skin immediately after bathing while the skin is still slightly damp. A good rule is to look for an emollient that is scooped from a tub or squeezed from a tube. Lotions contain higher water content and are generally not occlusive enough to help retain moisture in the skin. Creams that contain ceramides (which are deficient in eczematous skin) can be especially helpful. Specific over-the-counter products include Aveeno Eczema Therapy, Cetaphil, Curel, and CeraVe. Soaps should be pH neutral. Specific brands include Dove, Earth Friendly, Pears natural glycerin soap, Clearly Natural glycerin soap, and South of France glycerin soap. Caution is warranted with personal care products that contain fragrances as these can be irritating.

Self-Care

Moving the Body

Regular exercise is an important part of any healthy lifestyle. Studies looking at the effects exercise has on systemic inflammatory markers have found that a variety of inflammatory markers decrease with exercise.[25][26] While there do not appear to be any studies looking critically at the effect exercise has on atopic dermatitis specifically, studies evaluating effects on anxiety and depression are favorable.[27][28] Since these mood concerns are often present in patients with eczema, it is worth recommending a personalized exercise plan—especially to patients who have concomitant anxiety and/or depression. One caveat is that for many people with eczema, heat and sweat exacerbate symptoms of itching, and people with atopic dermatitis may limit exercise for this reason. It is important to counsel these people about how to minimize overheating and sweating: swimming, keeping exercise to a moderate level, exercising in a cool environment, exercising with a fan, and having cool towels or a spray bottle on hand. For some people, chlorine may also exacerbate symptoms of eczema. Seeking out a nonchlorinated or saline pool may be helpful. Rinsing immediately after swimming along with good skin hydration practices are especially important for people with eczema who would like to continue swimming. Yoga in particular might be a good place to start since many yoga practices incorporate mindfulness which can help with depression and anxiety.[29][30] Other movement practices that may be helpful include qi gong, Pilates, walking, and strength training. These can be done in a cool environment, and it is relatively easy to control levels of sweating. For more information, refer to “Moving the Body,” as well as related tools, such as “Prescribing Movement” and “Yoga.”

The guidelines in the table below are a good place to start, but ideally a personal exercise plan should be created and takes into consideration severity of symptom exacerbation and tolerance for exercise.

The World Health Organization’s Age-Based Guidelines for Exercise [31]

| Age | Duration | Exercise |

|---|---|---|

| 5-17 | 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day | Strength training 3 times per week |

| 18-64 | 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week | Strength training at least 2 times per week (Ideal: 300 minutes of moderate or 150 minutes of vigorous activity per week) |

| 60+ | Same as for the 18-64 year group, but add activities that improve balance | 3 times per week |