Moving the Body is one of the most popular Whole Health self-care topics Veterans will choose as they create their Personal Health Plans (PHPs). This overview focuses on the benefits of physical activity and ways to support people who want to increase their activity levels. It highlights the latest research related to exercise and other forms of activity, and it specifically discusses the potential roles of yoga, tai chi, Pilates, walking, and running. Moving the Body can improve flexibility, balance, and coordination, as well as strength and endurance. Even a few extra minutes of activity each day has potential benefits. This overview elaborates on what is covered in Chapter 5, “Moving the Body” in the Passport to Whole Health.

Key Points

- Physical activity is beneficial for a multitude of health issues, and it is one of the most powerful approaches to prevention we have as well.

- When starting an activity program, a person should take their current level of fitness into account. If a person is at risk or has not been active recently, they should see a provider before they begin a new activity plan.

- Mindful awareness can be helpful when it comes to Moving the Body. Tuning into the body is a common way to cultivate mindful awareness, and this helps people to both tune into any symptoms they might have as well as to focus on what feels most helpful when it comes to various forms of activity.

- There are many different forms of yoga, and hatha yoga, which involves various body positions, is one of the most familiar in the West. This approach has the benefits seen with other forms of physical activity and may have others as well, particularly in terms of cultivating mindful awareness. It seems to be helpful to people with nonspecific low back pain, cardiovascular disease, mental health, type 2 diabetes, and perhaps PTSD.

- Tai chi and qi gong, which involve (among other aspects) gentle movements that are performed in a very specific way, also show a number of potential health benefits, especially in terms of fall prevention and improved balances.

- It is helpful to become familiar with various resources you can share with Veterans on this topic, including various apps and websites.

Meet the Veteran

People say that losing weight is no walk in the park. When I hear that I think, yeah, that’s the problem.

—Chris Adams

Javier is a former paratrooper who served multiple tours in the Gulf War. During his service, he experienced multiple injuries to his joints, muscles, and bones. While he cannot remember how all of these injuries happened, he does recall many “hard hits” to his body while parachuting. After some of these impacts, he was not able to get up without assistance.

After completing his military service in 1991, Javier’s previously good state of health began steadily deteriorating. He now has chronic, debilitating bilateral knee and low back pain. He underwent arthroscopic knee surgery, which was complicated by both a post-operative wound infection and an allergic reaction to antibiotics. Soon after, he gained massive amounts of weight, and he eventually developed severe sleep apnea requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with supplemental oxygen. He began binge eating and rationalized his behavior by telling himself that it did not interfere with his normal functioning as a public school teacher, and it was better than using any drugs or alcohol. He does not take his prescribed extended-release oxycodone.

Things began to change after Javier “hit rock bottom,” passing out in front of his students due to sleep deprivation and exhaustion. Around this time, he remembered how a yoga class had previously made his back feel great. However, when he went looking for local yoga classes, he felt intimidated by the intensity of the classes. Luckily, Javier heard that his local VA was offering yoga classes, and he decided to establish care there so that he could see what his options were.

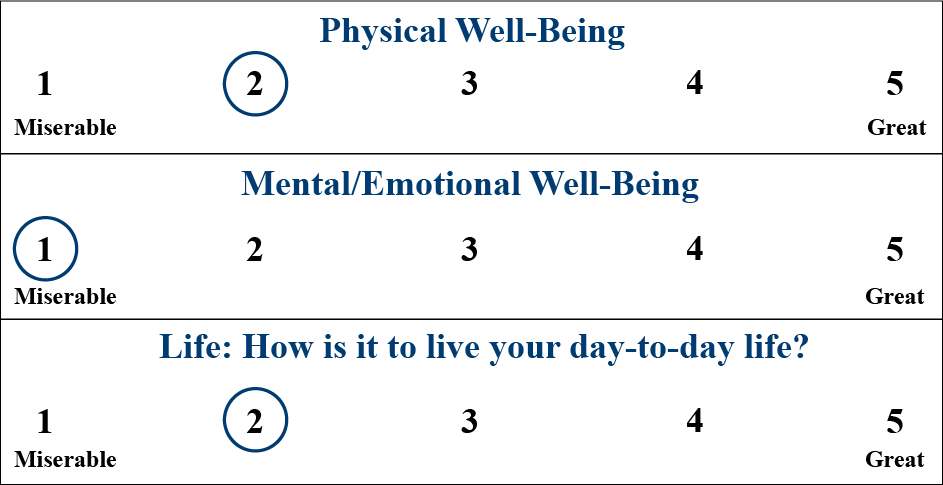

His provider asked him to complete a Brief Personal Health Inventory (PHI) prior to his visit. A few things stood out. First, his vitality signs were fairly low:

He denies being suicidal, but his provider felt compelled to check. His answer to the next question is reassuring along those lines.

What do you live for? What matters to you? Why do you want to be healthy?

Write a few words to capture your thoughts:

I love my kids. I have to be around for my family. I want to not hurt, mostly because I want to be the dad and husband they deserve.

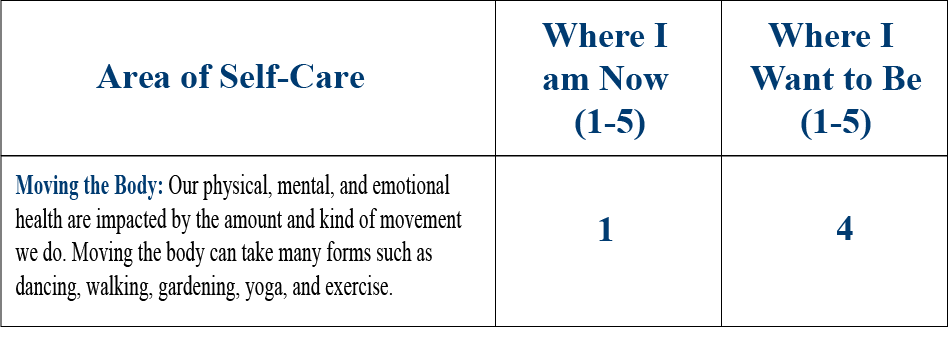

Javier’s answers on the “Where You Are and Where You Would Like to Be” section of the PHI were variable, ranging from 1 out of 5 (Food and Drink, Moving the Body) to 5 out of 5 (Professional Care and Spirit and Soul). Javier is clear that he wants to work on Moving the Body as his top priority right now.

When asked why he chose a 4 as “Where I Want to Be,” he says, “I doubt I even have it in me to get back up to a 5 like I was in the Marines. My body is broken.”

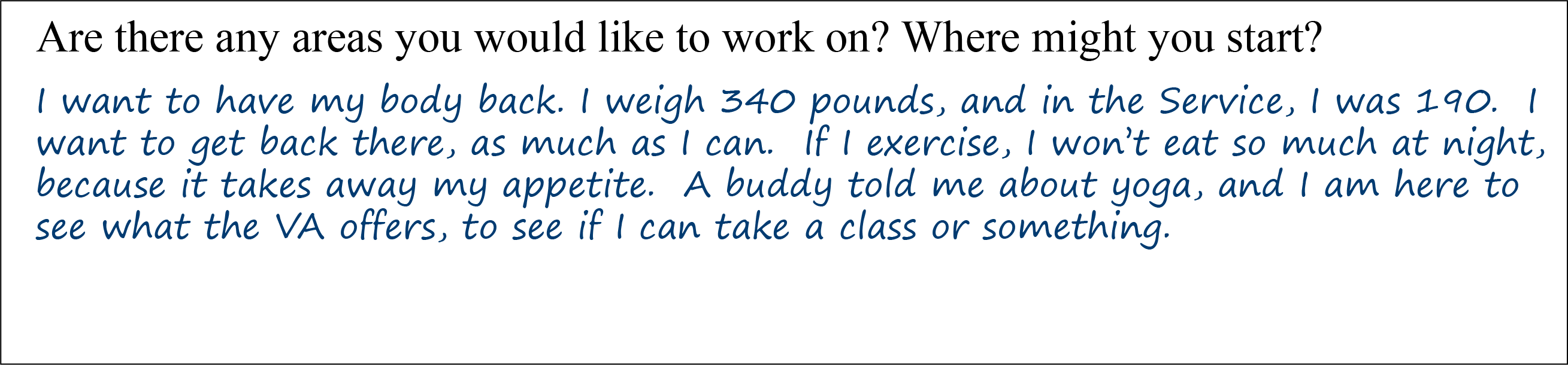

Finally, he helps write the Personal Health Plan (PHP) with his answer to the last PHI question:

How can Moving the Body serve Javier? What are some examples of various types of activity Veterans can consider, and how can they be recommended? What is important to know about safety? This overview answers questions about how to realistically bring physical activity into a PHP. It discusses different ways to move the body, including some that tend to be classed as complementary approaches. Benefits, harms, and suggestions for making referrals for these practices will be highlighted.

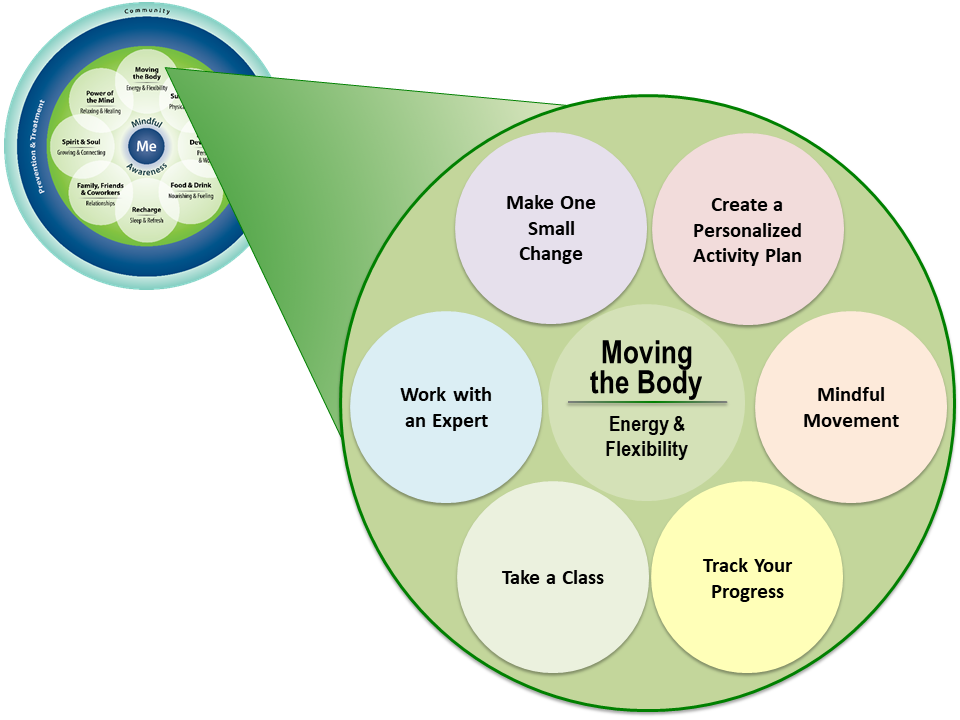

In the Whole Health Skill-Building Courses for Veterans, the diagram in Figure 1 is used to guide Veterans as they consider which topics related to Moving the Body they could add to their PHPs.

Benefits of Being Active

What if there was one prescription that could prevent and treat dozens of diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity? Would you prescribe it for your patients? Certainly.”[1]

—R.E. Sallis

It is difficult to find a component of health that physical activity does not have the potential to improve. In fact, there is a vast and growing field of research on how working one’s body can improve well-being, longevity and many medical conditions.[2][3]

In general, physical activity refers to any activity which moves the skeletal muscles of the body and increases energy output, whereas exercise refers to structured and repetitive physical activity with a specific intent—usually to improve some component of physical fitness.[4][5] Physical fitness refers to the development of specific skills including strength, flexibility, endurance, balance, and agility.[4] Presumably, similarly matched physical activity and exercise forms (e.g., walking briskly for a job versus walking briskly for exercise) have equivalent health effects. Accordingly, both exercise and unstructured physical activity have important health benefits and should be strongly encouraged.

Research shows that higher levels of physical activity are linked to seemingly countless benefits. These include, but are certainly not limited, to the following[6]:

- It lowers all-cause mortality rates[5][7] and increases life span.[8] Lack of physical activity, on the other hand, increases our risk of developing cardiovascular disease, cancer (e.g. of the colon and breast), type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.[5][9]

- Regular exercise mitigates the negative effects of aging, even if a person does not start exercising until later in life.[2] A 2018 trial found it improves overall physical function in long-term nursing home patients.[10]

- Numerous prospective epidemiologic studies have found that physical activity reduces our risk of dementia.[11] A recent study found that routine exercise (tai chi, resistance training, aerobic, and multicomponent) all improved cognitive function of community-dwelling adults over age 50, regardless of their baseline cognitive status.[12]

- There is also evidence that exercise preserves our ability to perform our activities of daily living and improves higher order skills (executive functioning) in both children and adults.[13] Our attention span, processing speed, and memory are also enhanced by exercise.[14] Kids who exercise perform better academically in many areas.[15]

- It has mental health benefits.[16][17] A 2013 Cochrane review found that exercise is moderately more effective than control interventions for symptoms of depression but not more effective than psychological or pharmacological therapies.[18] Consistent exercise decreases symptoms of both depression and anxiety,[19][20] but it is not clear how useful exercise is for major depression.[21] Even in the absence of a history of depression or anxiety, exercise is associated with increased psychological well-being,[22] and promotes brain cell growth.[23] It improves mental well-being in people with HIV and helps with ADHD.[24][25] It helps with cognitive function in schizophrenia.[26]

- It facilitates better sleep, though findings in this regard are variable.[27][28] It benefits people with obstructive sleep apnea.[29]

- It reduces pain. Exercise has moderate to strong evidence supporting its use for musculoskeletal pain.[30] An overview of Cochrane Reviews, while noting the need for more research, suggested that “physical activity and exercise is an intervention with few adverse events that may improve pain severity and physical function , and consequent quality of life” for people with chronic pain.[31] It is beneficial for low back pain.[32] A 2017 review found that aerobic and muscle strengthening exercises reduce pain and improve global well-being and quality of life, along with helping with depression, in fibromyalgia.[33] A 2018 Cochrane review noted there is at least slight improvement in physical function depression, and pain in osteoarthritis.[34] Walking markedly improved function in people with knee arthritis after 9 months.[35] Another review noted there is low-quality evidence showing benefit for exercises for hand osteoarthritis.[36]

- It is safe and beneficial in pregnancy, including for promoting overall wellness, managing appropriate gestational weight gain, and possibly preventing blood pressure and blood sugar problems.[37]

- It helps prevent or improve many other chronic health problems, including[38]:

- Cardiovascular disease and other circulatory disorders[39][40]

- Cancer (e.g. colon, breast, prostate, and renal). A 2017 “systematic review of systematic reviews” concluded exercise should be recommended for all forms of cancer because of “clinical, functional, and in some populations, survival outcomes.”[41] It improves quality of life in cancer survivors.[42] It does not increase cancer-related fatigue, but it is not clear if it decreases it either.[43]

- Type 1 and type 2 diabetes[44][45][46]

- Hypertension[35]

- Obesity[47]

- Osteoporosis[48]

- Stroke prevention and post-stroke recovery[49][50]

- Multiple sclerosis[51]

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease[52]

- Pulmonary hypertension[53]

- Heart failure[54]

- Renal failure (especially blood pressure management)[55]

- Intermittent claudication (pain in the legs from poor blood flow)[56]

- Psoriasis[57]

- Erectile dysfunction[58]

While physical activity is beneficial to health, sedentariness is associated with negative health effects.[7] According to the World Health Organization, inactivity is a leading cause of non-communicable diseases and poses a rapidly increasing health burden globally.[62] Forms of inactivity such as prolonged sitting contribute to the development of and diabetes.[63]

Overall, there seems to be a linear relationship between physical activity and overall health status,[5] with increases in health benefits seen at all stages of activity.[7] However, the greatest incremental benefit of physical activity is noted when we increase from no activity to some activity.[7]

Evaluating our Exercise Paradigm

Aerobic exercise… and beyond

In recent decades, much attention has been paid to the importance of aerobic exercise for disease prevention and health promotion. Aerobic exercise refers to activities that stimulate the heart and lungs and, in doing so, improve our ability to utilize oxygen. This emphasis is reflected in most national and international recommendations and guidelines for exercise.[2] Indeed, aerobic fitness in particular has been strongly associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular disease,[64] which remains the number one cause of death in adults worldwide.

In addition to aerobic exercise, research also strongly supports including other forms of fitness for health and disease prevention, especially resistance/strength training and flexibility exercises.[3] Studies show that if we are inactive, we lose 3-8% of our muscle mass each decade while replacing muscle tissue with increased body fat.[65] Even just ten weeks of resistance training can counter this process by increasing muscle mass and reducing body fat composition.[66]

Data also suggests that musculoskeletal fitness is strongly predictive of general health even in the absence of aerobic fitness.[5][67][68][69] This may be particularly important for the elderly for whom musculoskeletal fitness is strongly associated with maintenance of functional status and lower risk of developing diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), arthritis, coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke.[70] Moreover, studies show that resistance training is both safe and achievable in geriatric patients.[71] In light of our aging society, consider recommending resistance training in addition to (or if they prefer) as an alternative to aerobic exercise. Examples of resistance exercises are listed below.

Interestingly, resistance training can be turned into an aerobic exercise by incorporating the following suggestions:

- If using free weights, hold the weights in both hands and exercise both sides at the same time.[72]

- Vary resting time between sets during resistance training. This could mean starting with 45 seconds of rest between weight lifting sets, then shifting to 30 seconds of rest between sets, and ending with 20 seconds of rest between sets. This will theoretically result in increased aerobic capacity and a higher heart rate during the exercise period.

- Add plyometric exercises to a resistance training routine. Plyometric exercises include jumping lunges, squats, burpees, and depth jumps and can keep your heart rate elevated for up to 50 minutes after completing your exercise routine.[73] Studies have even shown that these exercises have comparable effects on the heart to sprint interval cycling.[74]

- Consider velocity training. This means lifting lighter weights with more repetitions to increase cardiac output.

Examples of Exercise

Aerobic Exercise

- Walking

- Dancing

- Jogging

- Cycling

- Swimming

- Tennis

- Cross-Country Skiing

Resistance Training

- Free weights and weight machines

- Resistance Bands

- Exercises using our own body weight (push-ups, squats, etc.)

- Medicine Balls

- Calisthenics

- Suspension Training

- Plyometric exercises

The risks of usual exercise

There is some evidence that physical exercise can increase our risk of developing coronary events and musculoskeletal injuries, but the overall benefits of exercise clearly outweigh these risks.[3][16] For individual patients, these risks and benefits should be carefully balanced. When we consider that death is a possible adverse event from an exercise intervention, our exercise prescriptions should be accompanied by a strong commitment to preventing harm.

Currently, there is no research distinguishing whether these adverse events of exercise occur in experienced or inexperienced individuals. There is also a paucity of research into what factors might reduce the incidence of exercise-related harms.[3] Accordingly, when providing exercise prescriptions, we may consider Hippocrates’ aphorism to “first do no harm.”

The incidence of exercise-related injuries in those engaged in moderately intense exercise are probably around 1% per month,[75] with highest rates amongst participants in resistance training, where up to 25-30% of participants report injuries that prompt them to seek medical attention.[76]

Injury rates due to exercise are much higher in military training, with estimates between 6-30% of trainees being injured per month depending on the type of training.[] One study found that 25% of men and 55% of women had an injury requiring an outpatient visit during 8 weeks of basic training.[78] Musculoskeletal injuries are a leading health concern for our military population and often result in chronic health issues.

Excessive or extreme exercise may be harmful in select patient populations.[79] Sudden cardiac death is a well-known risk associated with competitive athletics but is actually quite rare, with about 1 death per 100,000 marathoners.[80] Acute elevation of cardiac enzymes and adverse myocardial remodeling has been observed amongst marathoners, ultra-marathoners, triathletes, and long-distance cycle racers.[81]

There have also been recent attempts to define exercise addiction and/or dependence,[82] which, like overtraining, may be associated with negative effects on mood.[83] There is a well-known association between exercise dependence and eating disorders.[82] In particular, the triad of disordered eating, amenorrhea and osteoporosis is another important condition associated with impulsive and harmful behaviors related to excessive exercise.[84]

Musculoskeletal injuries are a leading health concern for military populations, often with lasting effects on health.

Mindful Awareness

Tuning in to Your Body

An important consideration for any exercise or physical activity program is how one listens to his or her body. While most of us have an intuitive sense of what we mean by “listening to” our body, we may frequently overlook this body-centered attention during physical activity. Alternatively, we might view discomfort and injury as expected side effects of athletic training, once again ignoring our body awareness. However, with a bit of reflection, most patients will agree that somatic and visceral attentiveness is important and can be cultivated through practice. One way to develop this mindful awareness of the body is by engaging in complementary and integrative health (CIH) movement practices such as yoga and tai chi.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Pause for a moment. Bring your awareness to your physical body. You may want to do a body scan. That is, take a moment to survey each part of your body. Bring your awareness to your feet, ankles, legs, abdomen and lower back, chest, and so on as you move up to your head. Reflect on the following:

- How do you feel physically?

- Now focus on your feelings. How do you feel emotionally?

- What about your thoughts right now—are they positive, negative, neutral?

- When did you last engage in any physical activity? Today? Yesterday? Last week? Longer ago?

- Might your level of physical activity explain, in part, how you feel physically and emotionally right now (whether positive or not so positive)?

- Is it time to engage in some movement?

- What will you do? When will you do it? How long will you do it?

- Is there an activity you have not done previously that you want to try in the future? If so, what is your first step in making that happen? When will you start the ball rolling regarding this new activity?

It seems that exercise-as-usual might affect one’s mindful awareness of the body in paradoxical ways. On the one hand, exercise may deepen and enrich one’s feeling and awareness of the body. For example, as a result of their training, many athletes report a newfound awareness of their breathing and posture. On the other hand, exercise may solidify patterns of ignoring and suppressing important biological cues. For example, “That crushing left chest pain is just weakness leaving my body.” The exercise itself is the same in both cases, but the outcome is very different. We might recognize this polarity within our own experience of exercise or in that of our patients. Moreover, it is very possible that ignoring pain cues contributes to a portion of the military training injuries mentioned above.

Many medical providers have seen the stoic patient who downplays symptoms and presents late for medical attention. Although this trait is sometimes associated with a “macho” personality, patients of all genders exhibit it. This behavior may not merely be due to an absence of knowledge about the signs and symptoms of illness; it may also represent an overt belief system or subtle relationship dynamic between the patient and his or her embodiment, the relationship they have with their physical self. Good providers can recognize such tendencies and modify diagnostics, treatments and recommendations accordingly, especially in the context of a long-term therapeutic relationship.

And what about the other extreme of body awareness? Again, many clinicians will recognize the type of patient who may be overly sensitive to their bodily feedback. Certainly such patients might prematurely withdraw from activity that is uncomfortable and/or need reassurance that they are okay. Guiding such patients to appropriate physical activity may also require certain sensitivity on the part of the clinician.

True to the Whole Health approach, an exercise program that includes mindful body awareness is probably more advantageous than the typical exercise plan. At the very least, mindful approaches to exercise can empower patients to perform other physical activities more efficiently and develop self-efficacy, self-awareness, and a greater capacity for self-healing.

How might we maximize the benefits and reduce the risks of physical activity? What range of options is available? The following is an evidence-based survey of several approaches to moving the body, with special attention to more mindfulness-based approaches. This is certainly not an exhaustive list; rather, it is a starting point for this discussion.

Yoga

Background

Yoga is an ancient system of contemplative practice that has become very influential in contemporary culture. Originating in India, where it has been practiced for millennia, yoga may be considered historically both a classical school of Indian philosophy and a multifaceted “psychospiritual technology.”[85] Today, yoga usually refers to a diverse set of exercises based on traditional practices that involve the body, breath, and mind. A typical yoga class in the United States will focus on the physical postures (or asanas) of yoga, with varying amounts of attention to breathing, relaxation, and/or meditation.

The recent increase in popularity of yoga in the United States is remarkable. A 1998 survey found that 3.8% of all U.S. adults used yoga in the previous 12 months.[86] Fourteen years later, the 2012 National Health Interview Survey found that number had risen to 9.5%.[87]

Benefits

Yoga has been found to help with a number of different health issues,[88] including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. It also seems to be helpful for mental health in general and with mood disorders. [89][90] Preliminary evidence supports its use with PTSD.[91] It also helps adults with type 2 diabetes improve glycemic outcomes and decrease complication risks and helps to control hypertension.[88][92]

Some of the most-reviewed research is for nonspecific low back pain. A 2017 Cochrane review noted low to moderate evidence of small to moderate improvements.[93] A 2014 review of systematic reviews, conducted by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, concluded that at this time there is good evidence to support yoga for improving functional outcomes in patients with chronic, nonspecific low back pain. Importantly, a 2017 trial found that Veterans with chronic low back pain had benefit from yoga even though they had “fewer resources, worse health, and more challenges attending yoga sessions” than others in the community.[94] A 2017 Cochrane review also found there is low to moderate evidence supporting yoga for back pain, but it is not clear how whether it is superior to other forms of exercise.[93] Yoga also shows promise for improving sleep,[95] menopausal symptoms,[96] COPD,[97] asthma,[98] and sexual function.[99] Cochrane concluded there is “moderate-quality evidence” that supports yoga to improve quality of life, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and sleep in women with breast cancer.[100] It can help as an adjuvant therapy for neurological problems like multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer disease, and neuropathy.[101] There are also benefits for functional status and fall prevention.[102][103] This list is by no means complete, and more research is needed in various areas.

Studies can be challenging to interpret, because there are so many different types of yoga interventions. Yoga research is limited mainly by heterogeneity of yoga interventions and difficulty blinding controls.[104][105][106]

Yoga has novel effects compared to usual exercise,[107] and there may be ways that yoga is superior to usual exercise for particular aspects of health.[107][108] Preliminary data demonstrates that yoga practice is associated with increased mindfulness traits[109][110] and decreases in stress levels.[87][110][111] Yoga practice consistently demonstrates enhancement of physiologic markers of relaxation, such as alpha wave activation on EEG and decrease in serum cortisol.[112]

Risks

Like exercise in general, the risks of yoga exercise seem to vary greatly by type of yoga and factors specific to practitioners.[113] Generally, adverse events due to yoga were found to have a 12-month prevalence of 4.6% and a lifetime prevalence of 21%, but serious events are rare (<2% of injuries).[114] Practice of the headstand, shoulderstand and lotus position, along with advanced breath practices, have produced a higher proportion of injury reports. [113] Certain outlying styles, such as Bikram yoga, which is performed vigorously in hot, humid rooms, are associated with more adverse events. [113] Patients with glaucoma should avoid inverted poses. Patients with osteopenia should avoid forceful practices. All participants should practice under the guidance of a qualified teacher.[113]

Making a referral

- Keep in mind that yoga is safe for healthy people.

- Yoga may share many of the benefits of other types of exercise.

- Yoga has demonstrated novel effects compared to aerobic exercise, such as increased mindfulness and increased physiologic relaxation.

- There is fair evidence that favors using modified yoga programs to treat non-specific low back pain, to prevent falls, and to preserve functional status for those at risk of decline.

- The type of yoga matters; when in doubt, try it out for yourself before you make recommendations.

- Look for certified teachers with the Yoga Alliance, who bear the designation of Registered Yoga Teacher (RYT).

- Consider the longevity of the studio, school or center a teacher is from.

- Learning yoga from books or audiovisual media is traditionally cautioned against; encourage patients working from media to seek out an in-person teacher.

Yoga Therapy

Yoga therapy (sometimes called therapeutic yoga) is yoga that is oriented specifically towards healing. Historically, the therapeutic aspects of yoga have been formalized by yoga’s sister system of medicine, Ayurveda.[115] For more information, see the section on “Ayurveda” in the Passport to Whole Health. Yoga therapy arose in recent years as practitioners sought to integrate current biomedical perspectives and yoga’s therapeutic aspects. Yoga therapy now has an international professional organization, the International Association of Yoga Therapists, as well as a peer reviewed journal and numerous training programs. A growing number of yoga teachers, yoga therapists and more conventionally-credentialed health-oriented practitioners are contributing to this developing paradigm. Research on the health effects of yoga usually does not differentiate yoga and yoga therapy, but the distinction is important. Most of the clinical trials using yoga employ an explicit therapeutic intent, as well as modifications of normal yogic exercise.

Making a referral

- Consider referring significantly injured or debilitated patients to a qualified yoga therapist rather than a regular yoga class.

- Refer to therapists who are experienced and actively practicing therapeutic yoga themselves.

- Choose therapists who have additional training and credentialing in health care professions, such as nursing or medicine.

Tai Chi

Background

Tai chi (also known as t’ai chi ch’uan or taijiquan) is an ancient Chinese martial art that has received considerable attention in recent years for its health effects. This system has its roots in Taoist philosophy, and the abbreviated form of its name tai chi also refers to an important concept from this view; it is literally translated as “supreme ultimate.” Tai chi has deep historical associations also with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) particularly in regard to theory and practice of harmonizing the energy or qi (pronounced “chee”) within the body.

In its contemporary form, tai chi is recognized by its slow, graceful gestures and soft flowing movements coordinated with the breath, conducted standing with slightly bent knees. The exercises are often poetically named (e.g., “grasping the bird’s tail”), and the rhythmic movements invite peace and clarity of mind.

Given its relationship to many of the martial arts traditions of Asia, tai chi’s many health effects are suggestive of the health potential of other martial arts forms. Although historically tai chi’s role in self-defense was more integral, many contemporary schools and teachers have de-emphasized the martial aspect of tai chi while underscoring the health and healing intentions. Tai chi is sometimes classified as an “internal” martial art due to its emphasis on internal processes of the practitioner, while more externally forceful martial art forms, such as karate, are classified as “external” martial arts.

Qi gong

Qi gong (also known as qigong, chi gung or chi kung) is another practice closely related to tai chi. The name of this system refers to a process of “cultivation of vital energy,” and its practices involve harmonizing and regulating the energy (or qi) internally through the use of posture, breathing and mental attention. It is said that tai chi is an expression of qi gong. Given this close relationship, some have argued that research about tai chi and qi gong should be considered a unified process.[116]

Benefits

The body of evidence supporting the health benefits of tai chi/qi gong is fairly robust. The strongest evidence for tai chi as a medical intervention is for fall prevention in the elderly, where it reduces falls by 43-50%.[117][118][119][120] This effect is most likely mediated by improvement in balance and muscular strength. Similarly, tai chi is likely helpful in both preventing and treating osteoporosis.[121][122] A recent review found tai chi shows promise for reducing fatigue.[123] Another review noted more research is still needed regarding tai chi and its effects on chronic pain.[124] Tai chi may also be beneficial for mood disorders[125] and improving psychological well-being.[117][121][126][127] A 2018 study found that tai chi is equivalent to pulmonary rehabilitation when it comes to outcomes for patients with COPD.[128] Qigong shows promise for helping people with cancer manage their symptoms, though more study is needed.[129]

Somewhat surprisingly, tai chi has an aerobic component.[121][130] Numerous physiologic benefits of tai chi have been observed including lowering of heart rate, blood pressure, and cholesterol.[121] Qi gong was found to beneficially enhance steroid secretion patterns and mental health in aging men. [131]

Risks

There is likely very low risk of harm doing tai chi. Given tai chi’s aerobic component, the general risks of aerobic exercise, as noted earlier, should be considered.

Making a referral

- Tai chi is a safe and beneficial form of exercise when practiced under the guidance of a qualified teacher.

- The benefits of tai chi may be particularly suited to an aging population.

- Tai chi has an aerobic component in addition to increasing strength and balance.

- Tai chi has strong evidence for preventing falls and increasing psychological well-being.

- Other martial arts classes also have health benefits.[132]

Pilates

Background

Pilates is a method of exercise that emphasizes controlled, coordinated movements and integration of the musculoskeletal system. Joseph Pilates (1880-1965), who suffered from debilitating illness as a child but recovered dramatically by adulthood, developed it in the early twentieth century. True to its therapeutic roots, Pilates is often offered in hospitals and therapeutic settings. It is explicit in its aim to develop aspects of physical fitness such as strength, flexibility and endurance, along with mental and neurological aspects, such as concentration and control.

Pilates classes typically focus on developing balanced muscular strength, especially in the postural and accessory muscles of the trunk, i.e., “the core.” The movements also target neuromuscular integration through use of the breath and attention to precision of movement. It uses a variety of specific apparatuses towards these ends. The system is appropriate for all stages of life and contains modifications for various levels of fitness.

Benefits

There is fair evidence that the Pilates method can improve flexibility and balance.[133][134] It may also help with muscle endurance.[1][135] It seems to show promise for low back pain, but it is not clearly superior to other forms of exercise. It is better than no exercise for women with breast cancer.[136] Evidence of clinically-oriented outcomes is lacking.

Risks

Pilates is a low-risk activity when performed correctly, and there are few reports of adverse events due to the Pilates method.

Making a referral

- Pilates is safe and likely helpful in improving balance, flexibility, and strength.

- In the hands of an experienced teacher or therapist, there is potential for Pilates to facilitate other aspects of musculoskeletal health.

- Look for instructors who have completed training through the Pilates Method Alliance.

Walking

Walking is man’s best friend.

—attributed to Hippocrates

Background

Walking has a somewhat unique combination of attributes to make it an excellent public health goal; it is accessible, safe, inexpensive, well tolerated, effective, requires no special equipment, and is amenable to structured promotion programs.[137][138]

Benefits

Walking programs can significantly improve cardiovascular risk, weight, and other cardio-metabolic indicators.[139] A 2018 review suggests there is need for more research, but the evidence base supporting walking for mental health is growing.[140] While most research about the effects of walking have been from epidemiologic studies, brisk walking (3-4 miles per hour) does fit the profile of a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise.[137]

Nordic or pole walking, which is basically walking with the use of ski poles or something like them, has received recent research attention and may have benefits over standard walking due to increased aerobic demand.[141][142] This practice might also decrease the risk of falls, and it is beneficial for people with cardiovascular disease.[143]

Pedometers are one way of motivating walking behavior. One caution is that inexpensive pedometers vary widely in estimating steps.[144] Programs that promote “10,000 steps” motivate participants to meet this signature number of steps daily; this corresponds to walking about five miles. Meeting this requirement meets or exceeds physical activity recommendations and likely improves health.[139] A 2018 review explored what is the optimal “running dose” for cardiovascular risk and noted that following the standard guidelines of 150 minutes/week of moderate or 75 minutes per week of vigorous exercise per week is reasonable.[39]

Risks

Walking is generally well-tolerated. However, special modifications should be considered. Patients with conditions such as memory impairment should be supervised as they walk. Walking tracks (which eliminate or reduce obstacles, inclines, uneven surfaces, and effects of adverse weather conditions) should be considered when balance issues are a concern.

Making a referral

- Due to its relatively low-impact nature, walking may be ideal for people who are weak, debilitated, or convalescing.

- Brisk walking (3-4 miles per hour) is an excellent moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Target 30-60 minutes per day.

- Nordic walking (with poles) may have health advantages over regular walking.

- Pedometers are effective for motivating walking behavior. Poor-quality pedometers may be inaccurate and thus misleading.

- Targeting 10,000 steps per day is a good starting “dose” for walking.

Running

Background

Running or jogging is, of course, a more conventional form of exercise. Running has received recent attention as far as its role in human evolution. There are numerous aspects of human physiology and anatomy that suggest the human body was optimally designed for running long distances. It is thought that this ability to run great distances was a prime advantage in early human history and possibly a major distinguishing feature of our species.[23][145]

Benefits

Exercise routines involving running are central to the conventional paradigm of exercise. Much of the general exercise literature is relevant to running. Running has been found to increase generation of nerve cells in the hippocampus, the brain memory center.[146]

Of note, equivalent energy expenditures of walking versus running are associated with similar improvement in cardio-metabolic variables; however, running achieves the target in less time.[147]

Risks

As noted previously, there is an increased risk of musculoskeletal injuries and coronary events with traditional forms of exercise.

Common musculoskeletal injuries related to running include plantar fasciitis, ankle sprains, hamstring strains, shin splints, stress fractures, iliotibial band syndrome, Achilles tendonitis, and runner’s knee.

Runner’s knee, or patellofemoral pain syndrome, involves excessive lateral tracking of the patella, which results in anterior knee pain.[148] Mechanisms for lateral patellar tracking may include over-pronation of the foot (with compensatory internal rotation of the femur) and relative weakness of the vastus medialis obliquus muscle in the quadriceps muscle group.[149][150] Hamstring tightness and dysfunction of the iliotibial band may also play a part in patellofemoral pain syndrome.[151][152]

To reduce the risk of patellofemoral pain syndrome, consider recommending avoidance of downhill running during the early stages of running.[153] It may also be worth advising the purchase of shoes that counter some patients’ tendencies to pronate. Similarly, orthotics can reduce pronation and, as a result, decrease the likelihood of developing patellofemoral pain syndrome.[154] Consider suggesting avoidance of high intensity interval training until pain resolves.[155] Encourage stretching before and after activities. Finally, provide optional exercises for strengthening the vastus medialis muscle. This may include cross-training with cycling.

Making a referral

- Evidence suggests that distance running may be a more physiologically correct form of exercise for our species.

- If you are short on time, running may be “more bang for your buck” compared to less intense forms of exercise.

- Routine pre-participation exams and advice should be provided to patients beginning running activities, especially in the context of comorbidities.

Back to Javier

Javier’s provider recommended a yoga teacher. Javier began to take weekly classes at his local VA and received additional teaching and coaching him via instructional videos and online chats. He started feeling better “almost immediately” after starting to practice. His teacher was blunt with Javier, telling him that if he didn’t change the way he was living, he would be at a high risk of dying young and leaving his family behind. This discussion led Javier to see that his behavior was totally inconsistent with his deep love for his family, and his motivation to be well.

Javier participated regularly in his prescribed yoga training program, which involved a “clean” plant based eating program, “dynamic tension” yoga exercises performed with a heart rate monitor, and guidance with modifying yoga poses to his particular needs. As he felt healthier, he was encouraged to read more about other ways to improve his health. He quickly lost weight through this program, dropping a staggering 100 pounds during the first year of his new lifestyle. He also eventually stopped needing crutches and knee braces to walk.

Today Javier’s pain is “manageable” without medication. He practices yoga daily and teaches yoga 4 evenings a week at the local VA, in addition to his day job. He has been working on other areas of self-care as well, and has markedly improved his sleep, nutrition, and stress level. He states that before his yoga program, “health was just what happened to me.” After adding physical activity back into his life, he realized that he is in control of his health. Now, as a result, he is able to share an active lifestyle with his family. Most importantly, he can more fully be there for them in the ways that matter most to him.

Whole Health Tools

Resources

- American College Of Sports Medicine

Excellent source of guidelines, recommendations and research on exercise. - American Council on Exercise

Non-profit “committed to enriching quality of life through safe and effective exercise and physical activity.” - Physical Activity Guidelines for America

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines and educational materials on physical activity. - CDC: Physical Activity

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s physical activity guidelines. - Yoga For Vets

Non-profit organization dedicated to help war Veterans “cope with stress of combat through yoga instruction.” - iRest in the Military

Branch of the Integrative Restoration Institute’s presentation of yoga-based practices in support of active duty military and Veterans. - Warriors at Ease

Training, certification and resources that bring “the healing power of yoga and meditation to military communities around the world.” - Yoga Warriors International

Large multifaceted program offering evidence-based yoga and mindfulness practices “to alleviate symptoms of combat stress, post-traumatic stress disorder and increase the resilience of critical task performers.” - The Huffington Post – How Yoga is Making its Way Into Our Military

An article discussing yoga’s emerging role in the U.S. military. - The International Association of Yoga Therapists

Professional organization with numerous publications and other resources dedicated to establishing “yoga as a recognized and respected therapy.” - Tai chi: A gentle way to fight stress

Basic information about tai chi from renowned Mayo Clinic. - Tai chi: A gentle way to fight stress

Basic video description of tai chi - Horse Stance Exercise

Instruction on a basic tai chi exercise from UW Health Integrative Medicine. - Pilates Method Alliance

Authoritative source of professional information and certification.

Author(s)

“Moving the Body” was written by Surya Pierce, MD and updated by Sagar Shah, MD (2014, updated 2018).