The Obesity Epidemic

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the prevalence of obesity in adults in the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey was 42.4% with no significant differences between men and woman or by age group.[1] The prevalence for both obesity and severe obesity was highest in non-Hispanic Black adults compared with other race- and Hispanic-origin groups. The etiology of obesity is multifactorial including genetic, psychosocial, behavioral, and environmental factors. Obesity is a chronic disease requiring a lifetime of prevention, treatment, and maintenance.

Overweight is determined by calculating the body mass index (BMI, defined as the weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Overweight is defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, obesity as a BMI of >30 kg/m2.

Useful Tools

- BMI Calculator

- Basal Metabolic Rate(calories needed to maintain current weight)

Many large epidemiologic studies have shown a relationship between all causes and cardiovascular mortality with increasing BMI.[2][3] Obesity in adulthood is also associated with a striking reduction in life expectancy for both men and women. Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of several chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, gout, heart disease, stroke, dementia, GERD, osteoarthritis, cancer, kidney disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Other reports have found higher disability and health care expenditures for patients who are overweight and obese.

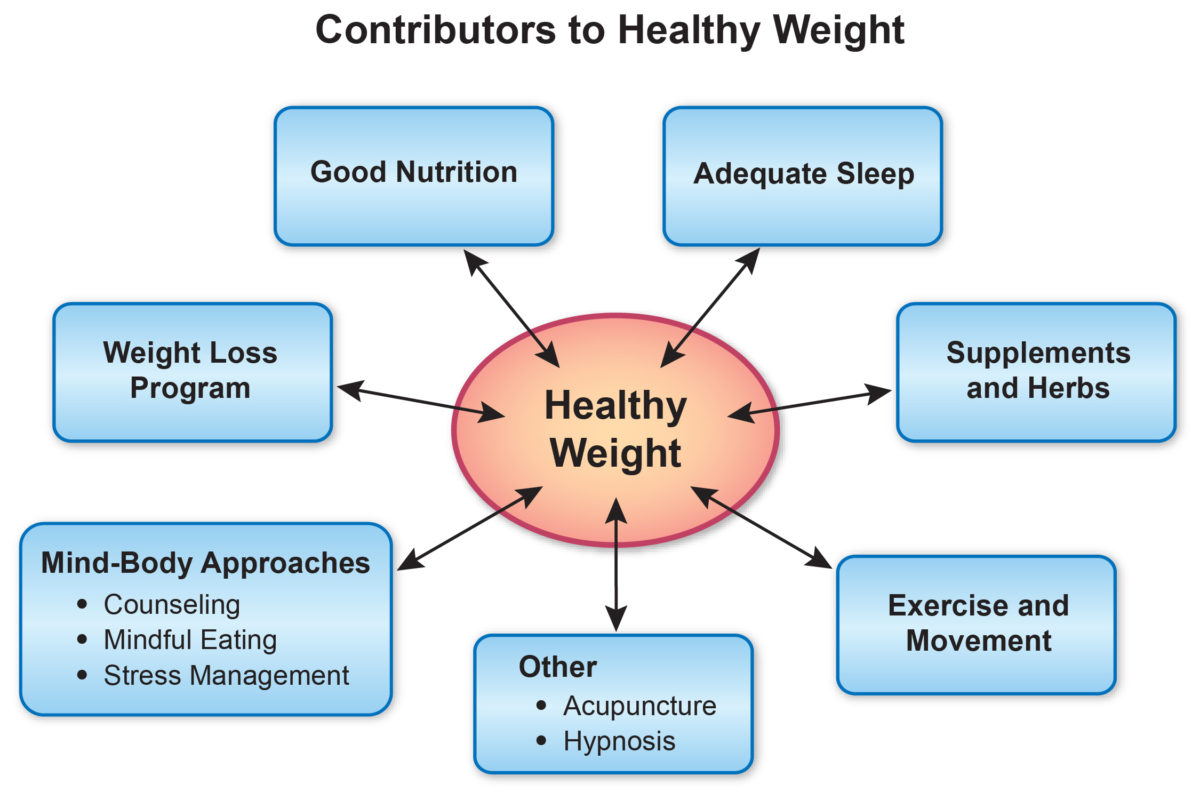

Approaches to Weight Loss

Changing the way patients approach weight loss can help them be more successful in the long-term. Most people who are trying to lose weight only focus on the goal of weight loss. However, setting the right goals and focusing on lifestyle changes such as following a healthy eating plan, watching portion sizes, being physically active, decreasing sedentary time, reducing stress, and getting enough sleep are much more effective.

The combination of a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity is recommended, because it produces weight loss that also may result in decreases in abdominal fat and increases in strength and cardiorespiratory fitness.[4] The initial goal of weight-loss therapy should be to reduce body weight by 5%-10% from baseline as this can have significant impact on health parameters.[4] With success, and if warranted, further weight loss can be attempted.

Weight loss should be about one to two pounds per week for a period of six months, with the subsequent strategy based on the amount of weight loss needed. The pacing of weight loss differs among individuals, and expectations should be realistic. Women, in particular, have difficulty losing more than one pound per week. One pound of weight loss requires a weekly deficit of 3,500 kcal from diet or exercise. A diet that is individually planned to help create a deficit of 500 to 1,000 kcal daily should be an integral part of any program aimed at achieving a weight loss of one to two pounds per week. Working with a nutritionist is ideal to develop this plan. A healthy approach to weight loss will include some or all of the following approaches:

- Good nutrition

- Diet or weight loss programs

- Exercise and movement

- Supplements and herbs

- Medication review

- Mind-body therapy

- Adequate sleep

- Acupuncture

- Hypnosis

Healthy Nutrition

General principles of a healthy diet include the following:

- Aim for a plant-based diet. The risk for many diseases is decreased with an intake of 8-10 servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Many plant-based proteins are complete and balanced sources of amino acids.

- Consume 20-35 grams of fiber daily.

- Choose a variety of whole grains and aim for carbohydrates low in glycemic index.

- Moderate fat in diet (25%-35% of total calories). Limit saturated fats. Avoid intake of trans-fatty acids (e.g., hydrogenated vegetable oils found in margarines, commercially fried and baked foods).

- Moderate sugar intake. Consume natural sugars in small amounts; avoid artificial sweeteners.

- Moderate salt intake. Choose and prepare foods with less salt. About 2,400 mg of sodium is recommended per day.

- Increase intake of omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3s reduce inflammation and risk for heart disease. Sources include fatty cold water fish, walnuts, flax, fortified eggs.

- Most adults need approximately 2 L of fluid per day. Many people eat when their bodies are actually giving them cues to drink.

- Eat intelligently. Establish regular patterns of eating; exercise portion control.

- Eat when hungry. Stop eating when full

Additional Reading on Nutrition

- Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy: The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healthy Eating, Walter Willett, (2005)

- Eat, Drink, & Weigh Less, Mollie Katzen and Walter Willett, (2007)

- Superfoods Healthstyle, Steven Pratt and Kathy Matthews, (2006)

- Eating Well for Optimal Health, Andrew Weil, (2000)

- Food Rules, Michael Pollan, (2009)

- The Obesity Code, Jason Fung, (2016)

Sugar Cravings/Reactive Hypoglycemia

While addiction to alcohol and caffeine are widely recognized, it is not well appreciated that many people are addicted to refined sugar. Reactive hypoglycemia is a term used to denote an exaggerated fall in the blood glucose concentration that results from excessive insulin secretion in response to a high-carbohydrate meal or high sugar load.

In his 2011 text Nutritional Medicine, Gaby explains that reactive hypoglycemia presents most frequently with one of two clinical responses in the body: adrenergic and neuroglycopenic.[5] When excessive insulin secretion occurs, blood glucose levels drop too fast and the body compensates by releasing adrenaline and other hormones that raise blood sugar. This results in a “fight or flight response” and symptoms of anxiety, panic, hunger, palpitations, tachycardia, tremor, sweating, and abdominal pain.[5] If the blood glucose peak falls slowly over a matter of hours, patients have delayed symptoms of headache, fatigue, and memory impairment.[5] Symptoms of reactive hypoglycemia tend to occur or become worse in the late morning and late afternoon or if a meal is missed. Symptoms are typically resolved by eating.

Practically, reactive hypoglycemia is a clinical diagnosis. A blood glucose level below 70 mg/dL at the time of symptoms and relief after eating will confirm the diagnosis. The oral glucose tolerance test is no longer used to diagnose reactive hypoglycemia because the test can actually trigger hypoglycemic symptoms. People who have reactive hypoglycemia frequently crave refined sugar or other simple carbohydrates, and they may also complain of many of the symptoms listed above. Eating these foods provides a temporary relief of symptoms as the blood glucose rises, but this also tends to trigger another episode of rebound hypoglycemia and carbohydrate cravings. This repetitive cycle can lead to overeating and obesity.[5]

The symptoms of reactive hypoglycemia, including the sugar cravings, can be managed with dietary modifications. Patients will feel best and have less rebound hunger if they eat several small meals and snacks throughout the day, no more than three hours apart. It is also necessary to eat a well-balanced diet including lean and nonmeat sources of protein, complex carbohydrates (low glycemic index), and fruit and vegetables. It is best to avoid or limit foods with high sugar content, especially on an empty stomach. These include refined sugars as well as natural sugars such as fruit juice, honey, and molasses. Alcohol should be minimized and patients should be counseled to eat food when consuming alcohol. With these dietary changes, many people will have withdrawal symptoms for two to three days until their bodies resume normal blood glucose control.

Diet & Weight Loss Programs

There are dozens of diets available to promote weight loss. In general, most diets work because there is an overall reduction in daily intake and calories. Some diets work better for some patients, however. For example, a low-carbohydrate diet is helpful for someone with insulin resistance or diabetes, while a low-fat diet might be helpful for someone with dyslipidemia. In general, the anti-inflammatory diet is helpful for most health conditions. A dietician can help patients determine which diet is best for them.

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

The Atkins diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet. The premise is that carbohydrates increase insulin levels and induce metabolic changes that cause weight gain.

The South Beach diet is a spin-off of the Atkins diet. The South Beach diet allows “good” carbs based on glycemic index and therefore is more balanced than the Atkins diet.

Low-Fat Diets

The Ornish diet is a low fat, high fiber, vegetarian diet. In addition to weight loss, this diet proposes to reverse and prevent heart disease.

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis including 68,128 participants assessed the effect of low-fat diets compared to other weight-loss dietary interventions. The results showed that low-carbohydrate interventions led to significantly greater weight loss than did low-fat interventions. Low-fat diets led to a greater weight decrease only when compared with usual diets.[6]

Balanced Diets

The Zone diet uses a “40-30-30” rule. The diet consists of 40% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 30% fat. It advocates only sparing use of grains and starches. The yet-unproven theory behind the Zone diet is that a balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats maintains insulin levels “in the zone” and therefore minimizes fat storage and inflammation.

The Weight Watchers approach is to assist members in losing weight by forming helpful habits, eating smarter, getting more exercise and providing support. A point system for food is used and daily targets typically assign a 1,000 kcal deficit. Local support groups as well as online programs are available.

The Anti-Inflammatory diet. A number of medical conditions are linked to too much inflammation in the body including heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic pain, inflammatory bowel disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Any long-term, healthy eating plan should try and incorporate the principles of the Anti-Inflammatory diet. The pertinent aspects of this diet include the following:

- Avoiding trans-fats

- Limiting fats that are high in omega-6-fatty acids including many saturated fats

- Increasing monounsaturated fats and omega-3 in the diet

- Aiming for 8-10 servings of fruits and vegetables

- Eating at least 30 grams of fiber daily

- Choosing whole grains whenever possible

Food-intake recording and regular weigh-ins were both identified as important aspects of weight loss planning and maintenance by successful members of the National Registry.

Of note, one 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that diets higher in protein may be effective in maintaining weight loss.[7] More research is needed to draw definitive conclusions about the best dietary approach for long-term maintenance of a healthy weight.

For more information, refer to the “Anti-Inflammatory Lifestyle” handout and the “Choosing a Diet” Whole Health tool.

Online Programs and Applications to Record Food and Physical Activity

- Calorie Count at Verywell

- MyFitnessPal’s

Moving the Body

Physical activity should be part of a comprehensive weight-loss therapy and weight-control program because it:

- Modestly contributes to weight loss in overweight and obese adults

- May decrease abdominal fat

- Increases cardiorespiratory fitness

- May help with maintenance of weight loss

Engaging in activity at least 150 minutes per week ensures health and fitness benefits, but this amount might not be adequate for weight loss. According to the National Weight Control Registry, a person in ongoing weight loss needs to exercise for approximately 60 minutes per day (about 400 calories expended daily).[8] Maintenance of weight loss requires 60-90 minutes of exercise per day if total calorie intake is not changed.[4]

Small changes in physical activity can have a significant impact over time. These can include walking or biking for transportation, parking further away from an entrance, and taking the stairs when possible. Some people find it helpful to use a pedometer or device that counts each step a person takes. Although 10,000 steps per day (5.0 miles) are recommended by some to be the benchmark for a healthy lifestyle, individual goals can also be set. Some early research suggests that yoga may also be considered a safe and effective movement practice to reduce BMI in overweight and obese individuals.[9] Exercise is a vital component to any program, yet most weight loss occurs through reducing total calories and improving nutrition.

Dietary Supplements & Herbal Remedies

Note: Please refer to the Passport to Whole Health, Chapter 15 on Dietary Supplements for more information about how to determine whether or not a specific supplement is appropriate for a given individual. Supplements are not regulated with the same degree of oversight as medications, and it is important that clinicians keep this in mind. Products vary greatly in terms of accuracy of labeling, presence of adulterants, and the legitimacy of claims made by the manufacturer.

There are a large number of supplements that are marketed for weight loss. In most cases, their effects are exaggerated, unrealistic, and not based on scientific evidence.

Their effects can be organized into the following three categories:

- Appetite suppressants

- Thermogenic agents

- Digestion inhibitors

Few weight loss supplements, however, have demonstrated both effectiveness and safety in clinical trials. The following four supplements are safe and can be recommended to patients attempting weight loss.

Multivitamin

Food cravings can be triggered by the human body’s lack of a certain vitamin or mineral. Taking a daily multivitamin reduces the likelihood of deficiency and may help with cravings.

Fiber (appetite suppressant and digestive inhibitor)

The role of dietary fiber in preventing and managing obesity in people is strongly supported by epidemiological and physiological studies. Additionally, increasing dietary fiber intake is safe and provides many health benefits. This includes reducing risk for developing coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes. Furthermore, increased consumption of dietary fiber improves serum lipid concentrations, lowers blood pressure, improves blood glucose control in diabetes and promotes regularity.[10] Fiber supplementation in obese individuals can also enhance weight loss. A 2017 review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials found that over the course of 2-17 weeks, soluble fiber supplementation reduced BMI by 0.84, body weight by 2.52 kg, body fat by 0.41%, fasting glucose by 0.17 mmol/L, and fasting insulin by 15.66 pmol/L compared with placebo.[11] Foods high in fiber typically have a lower glycemic index and increase satiety. Patients should obtain a daily dietary fiber intake of 20-35 gm through diet or nutritional fiber supplements including psyllium, guar-gum, methyl cellulose, or ground flax seed. These can be taken at a dose of 1 tbsp in 8-10 oz of water daily or 1 tsp in 6-8 oz of water before each meal.

Probiotics

Recent studies suggested that manipulation of the composition of the microbial ecosystem in the gut might be helpful in the treatment of obesity. Such treatment might consist of changing the composition of the microbial communities of an obese individual by administering beneficial microorganisms, commonly known as probiotics. Recent systematic reviews show that lactobacillus and bifidobacterium probiotic strains may reduce adiposity, body weight, and weight gain.[12][13] A 2018 review and meta-analysis included 957 participants across 15 studies with probiotic interventions ranging from 3-12 weeks. This review found that taking probiotics significantly reduced body weight, BMI and fat percentage compared to placebo.[14]

Camellia sinensis—green tea (thermogenic agent)

A systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1,226 participants found camellia sinensis to be effective for weight reduction and weight maintenance. Proposed mechanism of weight reduction is that it stimulates fat oxidation and energy expenditure. Doses included 270-1,207 mg daily (250 mg extract=1 cup).[15][16] A more recent meta-analysis showed the administration of green tea catechins with or without caffeine is associated with statistically significant reductions in BMI, body weight, and waist circumference; however, the clinical significance of these reductions is modest at best.[17] Use of green tea (not green tea supplements) for weight loss is unlikely to be harmful and appears to have a small benefit in weight loss.

The following supplements are found in commercial weight loss products. Most are lacking efficacy and safety data although some of them are known to be unsafe. Evidence does not support recommending these supplements to patients.

| Supplements | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|

| Ephedra[4,16,18] | Effective | Not safe |

| Chromium picolinate[4,16,19] | Not likely effective | Unknown |

| Conjugated Linoleic Acid[4,16,20] | Not likely effective | Unknown |

| Chitosan[4,16,21,22] | Slightly effective | Safe |

| Hoodia[4,16,23] | Not likely effective | Unknown |

| Bitter Orange[4,16,24] | Unknown | Not safe |

| Glucomannan[4,16,25] | Unknown | Safe |

| Garcinia (hydroxycitric acid)[4,16,26] | Unknown | Unknown |

| L-Carnitine[4,27,28] | Possibly effective | Safe |

| Pyruvate[4,29] | Unknown | Safe |

| Ginseng[4,30] | Unknown | Unknown |

| Guar gum[4,16,31] | Not effective | Safe |

| St. John’s Wort[4,32] | Unknown | Unknown |

Some other recent reviews and meta-analyses have assessed efficacy of other supplements and botanicals that may assist with achieving a health weight:

- Alpha-lipoic acid. Small, statistically significant, short-term effect on weight loss compared with placebo, with participants on average losing 1.27kg more than the placebo group.[33]

- A review of 33 studies showed no significant change in weight in overweight or obese participants

- Cocoa/dark chocolate. No significant effect on body weight, BMI, or waist circumference. Subgroup analysis did reveal significant reduction of body weight and BMI with a dose greater than/equal to 30 gm/day and a duration of treatment for 4-8 weeks.[34]

- A review of 45 randomized controlled trials found that supplementation with whole flaxseed at an amount greater than or equal to 30 gm/day for 12 weeks or more led to significant reduction in body weight, BMI, and waist circumference, particularly in overweight or obese participants.[35]

- A review and meta-analysis of 14 studies revealed that ginger intake contributed to a statistically significant decrease in body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, hip ratio, fasting glucose and insulin resistance index, while significantly increasing HDL cholesterol levels.

- Vitamin D. A review and meta-analysis of 11 studies showed a significant decrease in BMI and waist circumference. Supplementation took place from 1-12 months in these studies. [36]

Medications[33][34][35][36]

Orlistat is the only approved medication for long-term use in the treatment of obesity. It works by inhibiting fat absorption, but can lead to diarrhea when fat is consumed and there are vitamin deficiencies.

Phentermine and diethylpropion are appetite suppressants approved for use in the United States as adjuncts in the treatment of obesity. These agents demonstrate a modest weight loss benefit when combined with dietary modifications and exercise. No current evidence is available on the long-term risks and benefits of these medications.

Belviq (lorcaserin hydrochloride), was approved by the FDA for the treatment of obesity in 2012. Belviq works by activating the serotonin 2C receptor in the brain. Activation of this receptor may help a person eat less and feel full after eating smaller amounts of food.

Other medications including fluoxetine and topiramate are used off label for weight loss treatment, though the long-term benefits are also unclear. The combination drug Qysmia (phentermine and topiramate) was approved for weight loss by the FDA in 2012.

Unfortunately, drug treatment of obesity, despite short-term benefits, is often associated with rebound weight gain after the cessation of drug use and side effects from the medication. Occasionally medications that are used to treat other conditions might contribute to weight gain. Although it is not always possible to change therapies, a review of medications for the patient trying to lose weight can be helpful.

Medications That Might Promote Weight Gain [4]

- Antipsychotics (olanzapine, clozapine, risperidone)

- Antidepressants (SSRIs, tricyclics, lithium)

- Antiepileptics (valproate, gabapentin, carbamazepine)

- Diabetes agents (insulin, sulfonylureas)

- Steroid hormones (OCPs, corticosteroids)

- Miscellaneous (beta

Mind-Body Approaches

Counseling

Research has demonstrated the importance of regular visits with a physician or dietician when actively pursuing weight loss. Behavioral interventions, including motivational interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), should be adjunct therapies for any treatment plan. This is particularly true for any individual in which active mental health issues affect eating.[4][37]

Motivational Interviewing

The AHRQ National Guideline Clearinghouse recommends motivational interviewing to assist patient self-management in chronic disease care. Remember the 5As (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) of motivational interviewing. The Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) website contains resources for clinicians.

Mindful Eating

Eating patterns can also contribute significantly to the progression of obesity and must be addressed as part of any weight loss plan. Mindful awareness training is one way to shine a light on one’s relationship with food and the process of eating. Through mindful awareness practice, patients often develop an increased awareness of their bodies including the feeling of satiety and non-hunger reasons for eating.

The nature of our society is such that we often let our eating get out of our control for one reason or another. We eat quickly so that we can get back to work; we eat fast food because it is convenient and quick; we eat at restaurants because we are too tired or busy to cook for ourselves, and we eat processed food because it is cheaper and more accessible than fresh produce. Sometimes we eat foods with lower nutritional value because they taste good and give us an immediate burst of energy. Our bodies are hard-wired to like sugar and fat. However, because of the way we eat, we often don’t even notice or enjoy the flavors of our food. The practice of mindful eating is one way to recognize and then perhaps interrupt these habitual cycles. A 2018 review and meta-analysis of 18 publications on mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) for weight loss revealed that the mean weight loss was 6.8 lbs at post-treatment and 7.5 lbs at follow-up. This study concluded that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are effective in reducing weight and improving obesity-related eating behaviors in overweight and obese individuals.[38]

Overeaters Anonymous is a 12-step program to address compulsive eating. It addresses physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. More information, including how to find a local chapter, is available at Overeaters Anonymous website.

Mindful Eating Exercise

- Approach food with a desire to experience all it has to give you.

- Take the time to be aware of every sensation you get from each piece of food.

- Start with how you feel before you eat. Notice how hungry or full you are, and what made you choose the food you are eating.

- Notice how the food looks—the color, textures, and arrangement on your plate—and how the food smells.

- Take a single bite and focus on the sensation as it hits your tongue—the temperature, texture, and initial taste.

- Continue to focus on that single bite, chewing carefully and appreciating each sensation as it comes to you.

- When you are finished with that bite, pause to reflect on what emotions or thoughts you have about the food and about what pleasure you got from it.

- Wait to pick up another bite of food until you take that reflective pause.

- Start over with the next bite; continue to be aware of your food in these ways.

Online Resources for Mindful Eating

Additional Reading For Mindful Eating

- Women, Food and God, Geneen Roth (2010)

- Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life Thich Nhat Hanh and Lilian Cheung (2010)

- Eating Mindfully: How to End Mindless Eating and Enjoy a Balanced Relationship with Food Susan Albers (2003)

Stress Management

The stress response is the generalized response to any factor that has the potential to overwhelm the body’s compensatory ability to maintain homeostasis. Part of this response involves metabolic changes such as increasing cortisol levels that increase abdominal adiposity and insulin resistance. Stress may also affect food choice, both through lack of time for food preparation and by increasing preferences for higher-fat, energy-dense foods, thereby promoting positive caloric intake. On the deficit side, stress has been shown to reduce participation in leisure time physical activity; again potentially favoring positive caloric intake.

The epidemiological literature linking stress to weight gain has produced inconsistent results. One recent meta-analysis evaluated 14 cohort studies and found no significant relationship between stress and adiposity (69% of the analyses), but among those with significant effects, more found positive than negative associations (25% of the analyses vs. 6%).[39]

Based on our current understanding of the physiologic impact of stress on the body, a comprehensive lifestyle plan for weight management should include strategies for stress management. There are many other approaches that can be incorporated into one’s lifestyle such as hobbies, music (either performing or listening), physical activity, spending time in nature or with companion animals, yoga, etc.

Sleep

Both epidemiologic and clinical studies have shown that short sleep duration is consistently associated with development of obesity in children and adults.[40]

Consecutive sleep restriction (four hours per night) elevates the sympathetic nervous system and increases evening cortisol production, which has been shown to increase food intake and the accumulation of abdominal fat.[41] Sleep debt is associated with lower levels of leptin secretion.[42] Leptin is secreted from fat cells and transmits energy (fat energy) balance messages to the hypothalamus (brain center for hunger). As leptin levels decrease, the hypothalamus interprets the message that the fat cells need more food, and directs the body to eat more. Sleep restriction also leads to a significant increase in ghrelin, a hunger hormone produced and secreted from the stomach. Higher circulating ghrelin levels stimulate hunger and food intake (once again by the hypothalamus).[43] Sleeping fewer hours also results in more waking hours for food intake and calorie consumption.

Compared to individuals who work during the day, shift workers are at higher risk of a range of metabolic disorders and diseases including obesity. At least some of these complaints may be linked to the quality of the diet and irregular timing of eating, however, other factors that affect metabolism are likely to play a part, including psychosocial stress, disrupted circadian rhythms, sleep debt, physical inactivity, and insufficient time for rest and revitalization. There is increasing data showing the chronobiological aspects of food intake, such as time of day, meal frequency and regularity, and also circadian desynchronizations in shift work may affect energy metabolism and weight regulation.[44] In light of this information, patients should be advised to do the following:

- Limit shift work when possible

- Adopt a regular bedtime routine that mimics the natural circadian rhythms of the body and allows for 7-8 hours of sleep

- Limit night-time eating

- Eat regular meals

- Eat breakfast

Sleep Recommendations from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- Infants (3-11 months): 14-15 hours

- Toddlers: 12-14 hours

- Preschoolers: 11-13 hours

- School-age children: 10-11 hours

- Adults: 7-8 hours

Other approaches

Acupuncture

It has been observed that acupuncture depresses the appetite by activating the satiety center in the hypothalamus and boosting sympathetic activity through an increase in the concentration of serotonin in the central nervous system of obese people. Acupuncture can also stimulate the auricular branch of the vagal nerve, which has been shown to increase tone in the smooth muscle of the stomach, thus suppressing appetite.[45]

Although many studies have looked at the relationship between acupuncture and weight loss, most have been of poor quality. Non-standardized treatment protocols, lack of adequate controls and blinding, and short duration (<12 weeks) make these studies difficult to interpret. A 2020 review and meta-analysis of 12 studies demonstrated an association between auricular (ear) acupuncture and significant weight and BMI reduction.[46]

Hypnosis

There have been two meta-analyses conducted that look at the effect of hypnosis on weight loss.[47][48] They concluded that adding hypnosis as an adjuvant to CBT increased the amount of weight loss. A RCT conducted by Stradling and colleagues looked at hypnosis for stress reduction or energy-intake reduction and compared these groups to one that used dietary advice alone.[49] This study demonstrated that all three groups lost 2%-3% of their body weight at three months. However, by 18 months, only the group that received hypnosis for stress reduction had a significant weight loss relative to their baseline. This evidence suggests that hypnosis may be a useful treatment for obesity.

Prevention

Obesity is very difficult for many patients to reverse and is best treated early through prevention. Individuals should be weighed at all routine office visits and regularly at home. An anti-inflammatory diet with regular physical activity should be recommended. Counseling of overweight and obese patient should include discussions about health risks and should reinforce the importance of physical activity even if weight loss does not seem possible.

Authors

“Achieving a Healthy Weight’ was written by Jacqueline Redmer, MD, MPH, and updated by Vincent Minichiello, MD (2014, updated 2020). Sections were adapted from “Healthy Weight.”