As a clinician, your therapeutic presence can play a pivotal role in making a Whole Health visit successful. Therapeutic presence is how a clinician offers care. This overview summarizes 10 ways for a clinician to enhance their presence during a Whole Health visit.

Key Points:

- Through your therapeutic presence, you can bring Whole Health more fully into all your Veteran encounters, even with limited time during visits and virtual visits. This is also possible regardless of your specialty.

- There are many ways to be more present. Some examples include: fostering engagement, listening well, bringing more empathy and compassion, honoring differences in perspectives, and not letting time constraints interfere with what you can do.

Introduction

“The best effort of a fine person is felt after we have left their presence.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

This overview focuses on bringing Whole Health into your patient encounters through your therapeutic presence.

What you, as a unique individual, bring into your care of Veterans makes an important difference, above and beyond the interventions you prescribe, the procedures you do, or the referrals you make.

We all know clinicians who seem to be especially gifted when it comes to taking care of others. Their patients love them and have especially good outcomes. These clinicians are engaged in their work and seem to really enjoy it. When it comes to the art of healing, they are Michelangelo.

We also know colleagues who struggle to do well by their patients. Their patient satisfaction scores may be lower. They may not feel like they are making as much of a difference in their patients’ lives. They may find their work unenjoyable. They are at high risk for burnout. Not necessarily through any fault of their own, they may be in survival mode; for them, the art of healing may seem like an unreachable ideal.

How do you keep moving in the direction of being the best clinician—the best healer—you can possibly be? How do you bear witness each day to human suffering and yet still find fulfillment and meaning in your work?

Most research studies in medicine focus on variables we can quantify. Specific variables, like drug doses or length of stay in a hospital, are easy to measure because we can assign numbers to them. However, other non-specific variables have a substantial impact on outcomes too, whether they are measurable or not.

A 2006 study reviewed the National Institutes of Health’s 1985 data of a group of 9 psychiatrists who were treating depression.[1] The original study reviewed how much depression scores changed when psychiatrists prescribed the antidepressant imipramine versus placebo. When the data was revisited nearly 20 years later, researchers also broke results down based on each individual psychiatrist’s outcomes. That is, they evaluated for whether or not patients did better with depression depending on which of the 9 different psychiatrists they saw. Instead of the treatments, the providers themselves became the variables.

All other things being equal, outcomes depend on which psychiatrist offered treatment. Some patients noted significant improvement in their symptoms when prescribed medication and a smaller subset experienced improvement on placebo. Meanwhile, other patients described worst outcomes regardless of whether a medication or placebo treatment was prescribed.

As clinicians, we strive to make a positive impact on our patients' outcomes, like the psychiatrists in the study who noted improvement in their patients. For that to happen, we need to present the best version of ourselves at every visit.

It is not only about what you offer—prescriptions, procedures, handouts, etc.—but also about how you offer it.

How can your therapeutic presence—the “power of you”—support Whole Health? This overview summarizes 10 of the best-researched options we have for enhancing therapeutic presence. As you review them, keep asking how you can bring them more fully into your practice. At the end of the overview we will briefly discuss research on adapting this approach to telehealth visits. The 10 suggestions are as follows:

- Leave More Room in Your Toolbox

- Engage Your Patients

- Listen

- Practice With Compassion

- Honor Different Perspectives

- Focus On The Positives

- Learn From Mentors and Role Models

- Manage Expectations

- Use Your Time Wisely

- Model Healthy Behaviors In Yourself

Tip #1. Leave More Room in Your Toolbox

Tools are important in practice. We need to have something to fall back on as we are working with human suffering. Some of the nuts and bolts of our practices include the following:

- Gathering a chief complaint and a history of present illness

- Reviewing the problem list and medical history

- Forming a differential diagnosis

- Gathering data through physical examination and diagnostic studies to rule in (or rule out) possible problems

- Offering solutions and sharing our expertise

Those are important steps and we try to follow many of them already, but perhaps there is still more we can do, including the following:

- Apply all that you are doing to your own self-care. Identify your own Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP). Complete a Personal Health Inventory (PHI). Create your own Personal Health Plan (PHP). Refer to “Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care” for more details.

- If you are not dealing with an emergency, try to include at least a quick discussion about what really matters in every visitwith Veterans.

- Similarly, talk at least a little about how they are doing with self-careat each visit. The Passport to Whole Health and Whole Health Education website offer resources related to each self-care topic.

- If Veterans do not have a PHP, try to get them working on one, even if, for the time being, that only means looking over the Circle of Health and thinking about what they would like to talk about at a future visit.

- If they do have a PHP, check in with them about it and ask what they need in terms of next steps.Even if you cannot take those steps with them, you can help them think about who else can.

- When you can, discuss Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH). The Passport to Whole Health, chapters 14-18, focus on CIH as does “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part III: Complementary and Integrative Health.” Start by learning about the therapies that are now covered by the VA (the List 1 CIH Approaches). These include: acupuncture, meditation training, tai chi, yoga, therapeutic massage, clinical hypnosis, biofeedback, and guided imagery. Know how Veterans can access these therapies at your site. In terms of supplements, it helps to know what is on the VA formulary, such as fish oil, various vitamins and minerals, and melatonin. It is up to you to decide whether or not you want to recommend these therapies, but regardless of your perspective, you need to be able to have a conversation with Veterans about what they are and what is known about their efficacy and safety.

HOW DO I DECIDE WHAT TO RECOMMEND IN A PLAN?

When you are first learning about Whole Health and CIH approaches you may wonder how to decide what tools to use and when. What you and your Veterans decide to put into a PHP can be influenced by many factors, including the following:

- Evidence-based medicinein context. Of course, let information be evidence-informed as much as possible, but do not exclude options you think have promise, just because conclusive research findings are not yet available. In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association,[2]Braithwaite describes how six dangerous words, “There is no evidence to suggest,” if used without care, can discount the potential benefits of many therapies. The phrase also undermines the shared decision-making process, because it can lead some clinicians to immediately discount something a patient is interested in. Choosing the most suitable interventions requires both weighing the evidence andpractically determining, through firsthand knowledge about your patient, what is most likely to help them as an individual.

- Drawing from other ways of knowing. In addition to scientific understanding, it is likely that you will also guide the creation of PHPs based on other “ways of knowing,” such as your past experiences, pattern recognition, and gut feelings.

Numerous studies support the link between intuition and nursing expertise.[3] It has been suggested that with more expertise, clinicians begin to use different ways of knowing in order to handle challenging situations.[4] Five stages are described in a nurses transition from a novice to an expert, and these stages can be applied to professionals in other areas as well.

- In the novice stage, learning comes through instruction. You follow rules regardless of the context of a given situation.

- Advanced beginners begin to tailor their responses more carefully to the specific situation they are addressing.

- In the competence stage, actions are organized in terms of long-range plans that are broader in scale. A person begins to focus on the larger context.

- Proficient professionals view each situation as a whole. There is more synthesis of analytical thinking and intuitive understanding; it is easier to think in terms of the big picture.

- Experts have a more fluid and intuitive understanding than people in the other stages. They act naturally, almost without needing to analyze, particularly in more familiar situations. Intuition becomes more important. Decisions are informed not by anxiety (as is true for novices) but by a broader array of emotions.

Consider what stage you are at in your professional development. What ways of knowing do you rely on?

- Using the ECHO mnemonic. Using the ECHO mnemonic (Efficacy, Cost, Harm, Opinions) can help you decide whether or not a particular therapy—be it CIH or conventional—is worth trying.

- Efficacy. What does the research tell us about how well the intervention works? Are research findings significant enough to be clinically meaningful? Evidence-based medicine is relevant here.

- Cost. Is the therapy cost-effective? How much would a patient have to pay out of pocket for this therapy? Would services be covered at all by insurance or other social programs? How easy is it to access someone who offers the therapy?

- Harm. What does the research tell us about the potential for harm? How well can a given therapy mesh with other therapies a patient is currently receiving, (e.g., potential interactions between medications and dietary supplements)?

- Opinions. Is the therapy acceptable to a person when it comes to his/her personal opinions, beliefs, and culture? What sources of information are informing a person’s opinions? (To get a better sense of culture’s influence on health care, see the resources at the National Center for Cultural Competence.

Use the ECHO mnemonic to decide whether or not a particular therapy (conventional or complementary) is a good fit.

To learn more about ECHO, refer to “The ECHO Mnemonic” in the Passport to Whole Health.

- Searching for root causes. For people with a complex array of chronic medical issues, try to tell whether any seminal events are at the root of some their symptoms or concerns. For example:

- A poor diet can be linked to obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and any number of other clinical problems.The same same links are noted between insufficient physical activity, substance use, stress, poor sleep, and mental health issues, like depression. Consider how poor gut function and inflammation might contribute to ill health as well. (Refer to “Digestive Health” and related Whole Health tools to learn more.)

- Past trauma influences health, be it physical, sexual, or emotional. It is striking, for example, how often people with myofascial (connective tissue) pain can benefit from working through past traumas.

- Sometimes it can help to take a step back and approach a person’s array of health issues from different framework. For instance, considering a patient's case in terms of Traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, or naturopathy may offer new insights. (To learn more about these and other approaches, see the tool,“Complementary Approaches in the VA: A Glossary of Therapies and Whole Health Resources for Learning More.”)

- Asking the patient. Sometimes, it is as simple as asking the patient, “What do you think would help you the most right now?” or “What do you think is going on?” Whole Health is about patient-driven care; as the leading experts on themselves, patients co-create the PHP with you.

- Drawing from your personal experience. You can discuss and recommend CIH approaches more effectively if you have had direct experience with them yourself. Try them out as part of your self-care. Patients view their clinicians as much more believable if the clinicians seem to be practicing what they are preaching. For example, a group of patients who watched a video of a physician recommending diet and exercise found her much more convincing if she had a bike helmet and an apple on her desk.[5]

Tip #2. Engage Them

Mindful Awareness Moment

Take a moment to answer the following questions:

- In a year, how much time do you have to interact with any given patient?

- What percentage of the time do you think your patients follow your recommendations?

What approaches do you think are most effective to support behavior change? Education and information? Peer pressure? Telling them about what can go badly if they don’t make the change (threatening)? Focusing on how the change is connected to their core values? (Hint: The Whole Health Approach favors the last answer, though education is invaluable as well.)

We know that people follow through with taking their medications as prescribed about 50% of the time.[6][7][8] This number can drop to as low as 20% for people with chronic conditions. When the focus is lifestyle or behavioral change, about 20-30% of people follow through with clinician recommendations.[9] However, this number can increase to 70% if a person practices a behavior, such as supervised exercise, with a group of peers.[10]

Patient engagement has been referred to, even more than physical activity or healthy eating, as “The Blockbuster Drug.” If a Veteran engages, it starts to seem as though anything is possible, and the Whole Health Approach can fully work its magic.

If patients are disengaged, then no matter how elegant and elaborate the PHP might be, creating it is a waste of time. Engagement is defined as “…the desire and capability to actively choose to participate in care in a way uniquely appropriate to the individual, in cooperation with a healthcare provider or institution, for the purposes of maximizing outcomes or improving experiences of care.”[11] Sounds great, but how do you encourage people to become more engaged?

In 2017, Higgins and colleagues looked at 722 studies focused on engagement, and identified 5 key elements (forming the acronym “PACT-E”) that make engagement more likely:[11]

- Personalization. The more you tailor care to individuals—to their values or personal experiences—the more they will engage.[12] When people feel their care centers on them, they are less likely to die from a major event like a heart attack,[13]they trust their care team more,[14]and they are more likely to take their medications as prescribed.[15]

- Access. People need access to good information, guidance, and tools. They also need to have means to access care, including transportation to visits, or the social and financial support needed to follow through with the plan. A resource needs to be near enough that they can access it, and it needs to be available too; referring someone to another clinical or CIH practitioner only works if they have openings in their schedule. If something is not covered or costs too much, adherence to the treatment plan falters. PTSD, mobility limitations, or anxiety may keep a person from leaving home to seek care.

- Health literacy can also contribute to access challenges. Health literacy is a complex concept. It has been defined as “…the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”[16] A study of 502 Veterans, ranging in age from 22 to 82, found low, marginal, and adequate health literacy in 29%, 26%, and 45% of the Veterans, respectively.[17] If a person does not understand their health problems, cannot figure out how to take medications or supplements, or does not know how to make use of technology to access online resources, that can prevent them from following through with their PHP.

- Commitment. Commitment to a plan is essential. If your Veterans help create the plan, they will be more committed to implementing it. If they create the plan based on their MAP, so much the better. You can always gauge commitment on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being as committed as possible. If they are below 7, it might be time to shift gears and create a different goal or plan. Try to focus on their highest priorities first too; that is, do not focus on stress management practices if the source of their stress is actually that they are homeless and need help with that. Medical conditions, such as depression,[18]substance misuse,[19]dementia,[20]and severe fatigue can decrease motivation and engagement.

- Therapeutic Alliance. This is is one of the outcomes of having a strong therapeutic presence. Continuity of care, good communication, and knowing someone well can all support a strong therapeutic alliance.

- Environment (surroundings). Receiving care in a healing environment influences whether or not a person follows through with the plan. Refer to “Informing Healing Spaces Through Environmental Design: Thirteen Tips” for guidance on what makes health care facilities into optimal healing environments.

Tip #3. Listen

Part of therapeutic presence is generously receiving information ,not just actively giving advice. Attention is one of the greatest gifts we can offer. You know a visit is successful if a patient comments, “Wow, I have never had a doctor (or nurse, counselor, etc.) listen to me like this before.”

It is also a successful visit if you spend at leasthalf of the alloted time listening. The importance of listening may seem self-evident, but studies indicate that listening is a therapeutic agent in its own right. It strengthens clinician-patient relationships.[21] Studies indicate there is room for improvement among clinicians. For example, an often-cited 1984 study found that the average doctor interrupts a patient within the first 18 seconds of the patient talking.[22] A similar study 18 years later found that family physicians redirected their patients 23 seconds after the patients began to explain the reasons for their visit.[23]

It may sound simple, or even trite, but … do not interrupt! If you mindfully observe yourself during a Whole Health visit, you will find that it is very tempting to start talking about the plan early in the visit. Be strong! You might set a timeframe for yourself, such as waiting until the last 1/3 of the visit time before you discuss your specific recommendations or create a plan. When Veterans have time to share, they often start to write their PHPs themselves, based on what they realize as they talk to you.

When clinicians hear about the study findings related to doctors interrupting patients, they (justifiably) point out that, due to time constraints, interruptions are often a necessary evil. However, this may not be as much of a problem as we tend to assume. In a Swiss study, a group of internists were asked not to interrupt after asking the question “What brings you to the clinic today?” during 335 patient encounters.[23] The average length of time that patients spoke was 92 seconds, and the median was 59 seconds. 77% finished their statement in 2 minutes, and only 2% (we know who they are!) spoke more than 5 uninterrupted minutes. In every single situation, the physicians in the study reported that the information they collected was relevant.

One of the first things to remember, as you construct a PHP, is that doing so does not require you to be overly directive.

If possible, get out of the habit of feeling you are responsible for driving the conversation. As Epictetus put it, “We have two ears and one mouth so we can listen twice as much as we speak.”

In a study of people suffering with chronic back pain, researchers asked participants about the most important elements of a good back consultation.[24] You might imagine that one of the highest priorities would have been to get pain medications or diagnostic studies. This was not the case. Patients’ top priorities included the following:

- An explanation of what was being done and what was found

- Understandable information on the cause

- Receiving reassurance

- Discussing psychosocial issues

- Discussing what can be done

But the most important part of “Good Back-Consultation?” That the specialist listened to the patient and took them seriously. That is, they “felt heard” by their provider.

Tip #4. Practice with Compassion

In a 1973 study, 40 students from the Princeton Theological Seminary were asked to give either a nonspecific presentation on jobs for seminary students or a presentation focused on the biblical parable of the Good Samaritan, in which a man who is wounded by thieves and left by the side of the road receives help from a person from Samaria, after two others have passed him by.[25]

Researchers planted an actor in the alley along the route students had to take to reach the room where they were to give their presentation. The actor, laying in the middle of the alley way, moaned when someone approached. If someone asked him if he was okay, he was supposed to mention needing medications to help him breathe, which he hadn’t been able to take. Researchers wanted to see if students, including those who were asked to lecture about the Good Samaritan, would actually stop to be Good Samaritans when the opportunity arose.

Researchers varied the conditions of the study in terms of how rushed the students were made to feel getting to the lecture:

- Group I was not rushed, and 60% of them stopped to help.

- Group II was moderately rushed. 43% stopped to help, and the others walked by.

- Group III was very rushed. Only 20% stopped, and one person actually jumped over the “suffering” person.

It did not end up mattering which of the two different lectures students were asked to give; the time factor seemed to be what influenced helping behavior the most. Of course, this begs the question, how much do time constraints decrease clinicians’ compassion toward their patients? How much less compassionate do we become when we are running behind?

The terms pity, sympathy, empathy, and compassion are sometimes confused with one another in health care. It may help to think of the 4 terms existing on a spectrum,[26]from least helpful to a patient to most helpful:

- Pity, which is a feeling or discomfort at another’s distress, is often laced with a sense of being superior to the one who is suffering.

- Sympathy(“fellow feeling”) is about “feeling sorry” for another person’s hurt. One does not necessarily understand the other person’s perspectives or emotions, however.

- Empathyinvolves a greater level of understanding about another person’s situation, perspective, and feelings. When you feel empathy toward someone, you experience some of their pain for yourself, and there is a sense of the shared human experiences that are common to most people. Empathy is the ability to truly put yourself in another person’s shoes. Functional MRI imaging has shown that when we empathize with someone’s feelings, our brains actually activate the same neural networks that are active when we are directly experiencing those emotions for ourselves.[27] One way empathy contrasts with sympathy is that the person feeling empathy does not lose sight of whose feelings are whose. This may not be true for people who experience sympathy.

- Compassiongoes even further. Compassion is, “…the sensitivity shown in order to understand another person’s suffering, combined with a willingness to help and to promote the wellbeing of that person, in order to find a solution to their situation.”[28] Compassion happens when you feel empathy and do something about it.

Therapeutic presence is built upon compassion.

While many studies focus on empathy, some argue that compassion is a better concept to use in a health care context, since clinical practice most certainly involves not only feeling empathy but also doing something to help.

Regardless of which term is used, we know that caring deeply for your patients makes a difference. A 2013 review of 7 studies involving over 3,000 patients and 225 physicians concluded, “There is a relationship between empathy in patient-physician communication and patient satisfaction and adherence, patients’ anxiety and distress, better diagnostic and clinical outcomes, and strengthening of patients’ enablement.”[29] A 2016 review confirmed these findings and noted that additional studies indicate that empathy boosts health status, improves clinical outcomes, and makes patients more likely to rate their therapeutic relationships more positively.[30] More empathic clinicians deal with fewer malpractice claims and have greater job satisfaction as well.

In a 2011 study, 350 patients with colds were randomized to receive either no visit, a standard visit, or an enhanced visit. In the enhanced visit, clinicians paid particular attention to being as empathic as possible.[31] It was found that the 84 people who rated their providers as having prefect empathy scores had markedly better outcomes. Their colds resolved a day faster than the other groups’, and they rated their symptoms as less severe.

How do you cultivate greater empathy and compassion? Here are a few suggestions.

- Start by helping learners not to lose their innate empathy. A sobering 2008 study found that medical students’ empathy levels dropped markedly over their 4 years of training.[32]

- Compassion increases when one practices contemplative practices, such as loving-kindness, (also referred to as metta, or compassion), meditation. Mindfulness interventions with a loving-kindness component seem to increase self-compassion among health care workers and likely increase ability to be compassionate toward others in the process.[33] Chapter 10 of the Passport to Whole Health features a Loving Kindness Meditation you can use.

- Empathy is difficult to teach, but courses that focus on enhancing self-awareness, communication, and relationship-centeredness are thought to help clinicians be more empathic. Ekman and Krasner list 15 different courses that may be of benefit in a 2016 review.[30] Training in cultural humility, emotional self-awareness, and meaning making also increases a person’s empathy. Training in Motivational Interviewing likely helps as well.[34]

- Narrative medicine may also support cultivation of empathy and compassion.[30] For more information, refer to the Whole Health tool “Narrative Medicine.”

- Cultivating resilience and reducing burnout can also help.[35] For more information on resilience, and its shadow side, burnout, refer to “Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care.”

Tip #5. Honor Different Perspectives

When adequate information is not available, the good physician, who is always a good observer, will make appropriate decisions with inadequate information (the art of medicine).[36]

–J Willis Hurst

There are many different sources of knowledge, and there is great variation in how people determine if something is true or not.

We become very attached to our truths, and it is human nature to experience strong emotions (even fight or flight), if those truths are questioned. The key is to be aware of this in ourselves and to keep in mind that this happens for our patients as well. Honor the fact that people’s perspectives differ, while being clear on what you believe and why.

This a good time take a mindful awareness moment to explore this in more depth.

Mindful Awareness Moment

HOW DO YOU KNOW?

Take a moment and think of a statement you know to be true. Some examples:

- The sky is blue.

- Beethoven is a great composer.

- Avoid touching the pancreas during surgery if at all possible.

Now take a moment and ask yourself a series of questions:

- How do you know this statement is true? Where did the information come from? Did someone else tell you? Did you read it somewhere? Did you learn it through your senses, through direct personal experience?

- Suppose someone walked up to you and told you they disagreed with your truth. What would your response be? Would you feel any emotions? Would you want to argue with them? Why would you have that particular response?

The next time you have a conversation with a patient, try to be aware of moments where he or she expresses a belief that you disagree with. What do you notice? Do you feel an urge to correct them? How do you respond if they question your authority or knowledge?

When we ponder these issues, we are entering the realm of epistemology. Epistemology involves questioning what knowledge is and how we decide if something is true for us or not. When it comes to enhancing your therapeutic presence, thinking about this issue is essential.

Patients have more access to information than ever before. We, as clinicians, are no longer the keepers of “secret wisdom.” As of 2013, 81% of U.S. adults were using the Internet. Of those using the Internet, 59% reported searching for health information online within the past year, and 35% say they have gone online to try to make a diagnosis for themselves or someone else.[37]

There are many other sources of information beyond the Internet. We can learn by reading facts, making observations, having direct experiences, and being taught by others. We can also learn by being part of a culture or religious group and through stories and narratives. Many people also trust in the knowing that comes through instinct, intuition, or flashes of insight.

If a clinician derives truth through one perspective, and a patient derives it from another, there is the potential for some disagreement, for an “epistemological clash.” An important part of writing PHPs is being able to collaborate so that neither patient nor clinician has to compromise too much in terms of what they believe. These are times where you need to bring out your best diplomacy skills.

Consider the following whenever a difference in opinion (an epistemological clash) arises:

- Be clear on why the other person believes what he or she does. Was someone they know helped by a particular therapy? Did they see something in the media? Did they hear about it from a friend?

- Know your own thoughts and feelings about a particular issue. If you are feeling strong emotions around differences in beliefs between yourself and your patient, it is important to explore why. Some ways of knowing are based on logic and rationality, but how we feel about what we know might not be rational. We have all seen discussions of treatment plans become heated.

- Share what you know about a given therapy, test, etc. Educating and offering your experience is one of the main reasons why people come to see you, after all. In order to do give your informed opinion, you need to do your homework so that you have adequate knowledge to offer.

- Consider whether you would suggest alternatives to what your patient is doing or may want to do. Ask yourself how you would bring up those other options in the conversation.

Of course, being understanding of a person’s beliefs and why he or she has them does not mean compromising your own. Find a balance. Share your beliefs while recognizing that personalized care is also about respecting where a person is coming from, not just recommending the treatments you think are best.

“The ordinary patient goes to his doctor because he is in pain or some other discomfort and wants to be comfortable again; he is not in pursuit of the ideal of health in any direct sense. The doctor on the other hand wants to discover the pathological condition and control it if he can. The two are thus to some degree at cross purposes from the first, and unless the affair is brought to an early and happy conclusion, this divergence of aims is likely to become more and more serious as the case goes on.”

—Wilfred Batten Lewis Trotter

Tip #6. Focus on the Positives

“The findings of this investigation show that there is a point in being positive: patients who present with minor illness show greater satisfaction and are more likely to have recovered from their illness within two weeks if they receive a positive rather than a negative consultation.”[38]

—KB Thomas

Most clinicians are trained to find the problem and fix it. This is important, but many conditions cannot simply be fixed—especially chronic ones. An important aspect of the Whole Health Approach is to focus on what is right as well.

What are a person’s strengths? What areas of the Circle of Health are they doing well with? What gives them resilience? Focusing on the positive can have important health benefits for your patients, strengthen your connection with them, and prevent you from becoming cynical or burnt out.

The following are 4 ways to focus on the positive and may be helpful to you as you cultivate your therapeutic presence: Using the Aspirations Model; bringing in Positive Psychology; enhancing optimism; and practicing gratitude.

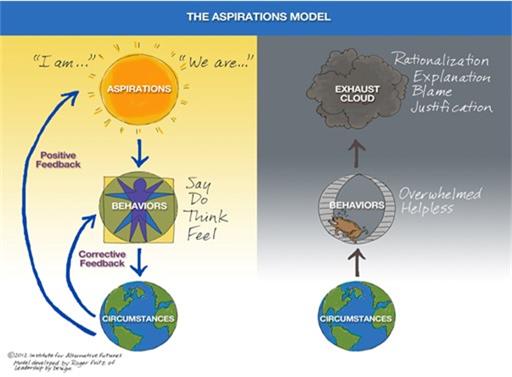

USING THE ASPIRATIONS MODEL

A key element of Whole Health clinical teaching is the Aspirations Model. The Aspirations Model was created by Institute for Alternative Futures, found at the Alternative Futures Association website. The group works with various organizations to help them center their work on their vision of the future, on their Aspirations.

The right side of the Aspirations Model, illustrated in Figure 1, represents an all-too-common way that we might experience some part of our lives, be it our health, our home environment, or our work. We play a defensive game, reacting over and over again to circumstances we are beset by until we feel trapped like a hamster on a wheel. This can lead to a sense of disempowerment and weariness (the “exhaust cloud”). Many patients are at a high risk for feeling this too, given that they have so many different chronic health issues that keep them constantly seeking help.

Alternatively, looking at the left side of the diagram, it is possible to focus on our aspirations—where we would like to be. We ground our day-to-day choices and actions on those aspirations. We may ask mindfully, at any given moment, how much our actions in the present are leading us to our desired outcomes. This requires not only responding skillfully to circumstances that confront us, but also shifting our behaviors to be better aligned with our values.

Collaborating with patients to create their mission statement is one way to focus on aspirations. You can provide better care if you know individualized, values-informed reasons for why they want to be healthier. You might feel more invested in someone’s outcomes if you know what really matters to them. Aspirations hone in on the “Why” of what we do, and that is the essence of Whole Health.

Figure 1. The Aspirations Model.

Reprinted with permission from Institute for Alternative Futures.[39]

With a clear goal in mind, and with the freedom to dream and aspire to something more, a person can experience positive change. And if clinicians focus on and practice according to our own aspirations, our experiences and work can also change for the better. We can make positive changes for our teams, clinics, and hospitals. The Aspirations Model can inform the workings of an entire Whole Health System.

BRINGING IN POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Physicians learning to do Integrative Health consultations are encouraged, when they are creating PHP’s with patients, to highlight what their patients are doing right. Even if there are times when the only positive thing you can come up with to say is, “Thanks for taking the time to show up,” that is something. People come to a visit because they believe that it will make a difference in some way. You never know how much time and energy a person may have invested simply to come in and be seen

Always take a moment to voice to patients what they are doing well and what they have working in their favor. This improves patient outcomes.

Focusing on what someone does well—their positive attributes and strengths—is at the core of Positive Psychology, which was first introduced in 2000.

The field of positive psychology is about valued subjective experiences: well-being, contentment, and satisfaction (in the past), hope and optimism (for the future), and flow and happiness (in the present). At the individual level, it is about positive individual traits: the capacity for love and vocation, courage, interpersonal skill, aesthetic sensibility, perseverance, forgiveness, originality, future-mindedness, spirituality, talent, and wisdom. At the group level, it is about the civic virtuesand the institutions that move individuals toward better citizenship: responsibility, nurturance, altruism, civility, moderation, tolerance, and work ethic.[40]

A 2013 meta-analysis of 39 studies with 6,139 participants concluded that Positive Psychology interventions led to improvements in subjective well-being and psychological well-being that, while small, were both significant and sustainable.[41] Specifically, benefit was found in the reduction of depressive symptoms. More studies are needed, but Positive Psychology interventions seem to be quite safe.

ENHANCING OPTIMISM

Optimism is one important aspect of Positive Psychology. Optimism reflects the extent to which people expect, in general, that their futures will turn out well. Higher levels of optimism correlate with many health benefits, including the following:[42]

- Better sense of well-being in times of adversity

- Higher levels of engagement, less avoidance or disengagement

- Greater likelihood of taking more steps to protect one’s health

- Better overall physical health

- More success with relationships

- Higher income because higher levels of educations are pursued

One review concludes, “…the behavioral patterns of optimists appear to provide models of living for others to learn from, and we know that optimism, in general, improves health outcomes.”[42]

A reasonable amount of optimism can improve the quality of care we offer. Simply saying “I am optimistic that you will get better” in a PHP may have a significant impact.

PRACTICING GRATITUDE

Gratitude, which is associated with habitually “…focusing on and appreciating the positive aspects of life,” can also be good for one’s health. (Refer to “Creating a Gratitude Practice”) Focusing on what you appreciate about each Veteran you see can help you relate to him or her better. Gratitude is associated with a number of benefits, including:[43][44]

- Higher levels of alertness, determination, attentiveness, vitality, and enthusiasm

- Increased time spent exercising

- More sleep that is of better quality

- Fewer physical symptoms, including headaches, coughing, and pain

- Better immune function

Tip #7. Learn from Mentors and Role Models

Mindful Awareness Moment

Here is a simple mindful awareness moment. Answer the following:

- Who is the most gifted healer you know?

- Why did you choose them?

- How do they demonstrate therapeutic presence?

How can you be more like them?

Mentors and role models can help you cultivate your therapeutic presence in a number of different ways.

- Having them in your life makes you more resilient.[45]

- Receiving good mentoring and role modeling allows you to pay that same experience forward; you can role model for future generations of healers.

- Good mentoring, according to one recent review, led to better relationships with colleagues and improved networking. It also made people more confidentand better-able to manage stress. It gave people a sense of being supported.[46]

For help finding a role model, check out the role model finder at Academy of Achievement. and fill in their simple questionnaire. You can read about well-known people who answered the questions the same way you did.

Here are suggestions from some people who have been practicing Whole Health for quite some time:

- Learn to protect your own energy. Imagine that you are in your circle and your patient is in theirs. Don’t stay totally out of their circle, or you won’t connect. Don’t go totally into their circle, or you will get too caught up in all their suffering. Put one foot in their circle, and let the dance begin!

- Start with a few concrete goals—one diet change, one exercise, one breathing/meditation, etc. Some people throw too many suggestions at folks, and it overwhelms them. Give them 1 or 2 suggestions, but save others for a follow-up visit.

- Rely on your resources. Use handouts, blurbs, and spiels about things you recommend frequently to save time. Train your teammates to help with education and skill building.

- Be an advocate on a patient’s journey toward wellness, but do not hesitate to (gently and compassionately) call them out on maladaptive, irresponsible behaviors. Sometimes it works, sometimes it backfires. Put your best motivational interviewing skills to work. Ask questions like these: Do you feel that behavior is helpful for you?” and “What purpose does it serve?

- Balance getting the work done with the need to keep learning.

- Reflect on the stories patients tell What do they really need? Be careful not to get so caught up on your own ideas for what you think they should do that you lose track of theirs.

- You have to model Whole Health yourself if you want to be effective.

- Take breaks. Give yourself a momentary pause between Veteran visits to hit the reset button. Pause to ask what you need, from time to time.

- Compassion for others begins with compassion for yourself.

Tip #8. Manage Expectations

If you are the average person driving on the road and you are hit from behind, you have a 10% risk of developing whiplash neck pain. If you are a demolition derby driver, hit behind hundreds of times a year, your risk is only 0.25%.[47] Why the difference? There are probably many factors, but one is expectation.

Both patient and clinician expectations can influence outcomes.

Expectations affect health. Chronic pain patients who know they are receiving a dose of morphine through an IV experience pain relief twice as quickly as similar patients who do not know the infusion has been given. Conversely, if a person receiving pain medication is told it is going to be turned off, their pain returns hours before pain returns for people who got medication but were not aware it was discontinued. The same holds true for people with anxiety who do or do not know the status of when a diazepam infusion is started or stopped.[48]

Even studies with open-label placeboes find that expectations lead to clinical benefits. For example, a 2016 trial involving 97 people with chronic low back pain found that people who received a placebo—and they were told it was a placebo—for 3 weeks had an average drop of 1.5 points in their pain rating on a 10-point rating scale.[49] Controls’ pain scores only changed an average of 0.2 points. Usually a change of at least a point is thought to be clinically meaningful in studies like this.

Patients’ expectations give power to the placebo effect, but what about clinician expectations? A multicenter study focused on 9,900 patients who were referred by 2,800 different physicians for either acupuncture or “usual care” for chronic pain. When everything else was controlled for, outcomes for both treatment groups were better if referring physicians had high expectations that the interventions would work.[50] Physicians’ expectations were associated with better outcomes for both pain intensity and physical functioning, even though researchers ensured that there was no overlap between provider expectations and other variables, such as baseline pain levels, illness duration, co-morbidities, and age. That is, it was not that the doctors consistently rated the patients with the worst symptoms as the ones who would not benefit, and yet their feelings about the usefulness of the treatment still seemed to affect outcomes. Overall, the degree of change in outcomes was relatively small in terms of being clinically meaningful, but statistically, the fact that provider expectations made such a difference was noteworthy.

Tip #9. Use Your Time Wisely

One of the first questions clinicians ask when they initially hear about the Whole Health Approach is, “How much more time will this take me?” As the Good Samaritan study (described earlier) showed, being rushed chips away at our compassion. It is already difficult to see patients, serve on committees, deal with reminders and metrics, and still manage to find a good balance between work and other aspects of our lives.

Clinicians who are rushed are less likely to offer personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care.[51] Research indicates physicians with high-volume practices and shorter visit lengths prescribe more drugs. Shorter interviews contain less prevention and health-promotion activity as well. Addressing these behaviors requires mindful awareness. You must be able to pause and recognize when you are reaching for a prescription pad or relying on a “quick fix” because of time pressures. What if there were other, equally efficient things you can do to Whole Health more fully into the equation without losing time in the process? Remember, your job is not necessarily to fix the issue so much as to empower them to make changes. Motivational Interviewing skills, which most VA clinicians have learned, are helpful here. (For more information, see a List of Motivational Interviewing Resources from the Center for Evidenced-Based Practices.)

How much time one can give to a Whole Health visit will vary based on where you practice and what type of health professional you are. However, even in 5-10 minutes in the emergency department or during an acute-care visit, it is possible to offer a few quick suggestions. Moreover, Whole Health Care can become a group effort—by a trans-disciplinary team. If a Whole Health Partner or Whole Health Coach has already helped a Veteran complete a PHI, explore MAP, and outline some initial PHP goals, this expedites the process and simplifies future clinical visits. If you know that your teammates have various other aspects of self-care covered, you can focus on the specific skills and knowledge you are able to contribute. As they say, “It takes a village to do Whole Health.”

Whole Health is much more a matter of perspective than a matter of how much time is available. The Whole Approach may lead to a visit with different content, but that does not mean the visit necessarily has to be longer. Simply shifting the focus of the visit—what you choose to talk about—can change everything. Bringing more of a therapeutic presence to the visit, using all the tips offered in this overview, can take your interactions with Veterans in new directions but not necessarily cost you time.

Here are some suggestions (based on hard-won experiences of colleagues who practice Whole Health) regarding Whole Health and time use:

- Set agendas

Set the agenda right from the start of the visit. The average patient has 3 concerns to address during a primary care visit, despite the fact that he or she may be asked to identify just one when the visit begins. Explore what your patient’s concerns are right away—not when your hand is on the door to leave. Remember, as they share their concerns, not to interrupt! Some clinicians will set a three-concern limit early in a visit, if possible. A 2007 study found that if clinicians ask the question, “Is there somethingelse?” versus “Is there anythingelse?” unmet concerns are decreased by 78%.[52] As an added bonus, clarifying agenda is likely to lead to greater patient satisfaction.

Although we all dread long written lists, they do have a number of advantages. First, they are testimony that the patient is engaged in his or her health care and in the visit, since the patient has taken some time to think ahead and write down his or her concerns. Second, a list makes it easier to negotiate what is reasonable to cover at this particular visit. You don’t have to spend time uncovering the patient’s agenda because the patient has penned it out for you. In my personal experience, people with written lists rarely fail to identify otherwise hidden concerns… The conversation could start this way: “I see you have a list today. I am pleased you have thought ahead about what we might cover at our appointment. Let’s take a minute to look at the list together and make sure we cover the most important items today.[53]

- Prioritize

Working together with the Veteran and the rest of the team, come up with just a few priorities during each visit. When it comes to the PHP, what matters most? Yes, you want patients to achieve their MAP, and yes, there are probably 10 or more suggestions you could offer them at any given time. Pace things; it is okay to introduce these suggestions gradually, and ideally, the patient should be the one who is bringing them up. Take advantage of follow up visits, if you can. Many patients do best if you just change just one variable at a time. Collaborating on decision-making with the patient is crucial.

- Take small steps

Research tells us that even small steps can bring about significant health improvements. For example:

- A 2%-5% weight loss can significantly reduce cardiovascular risk and risk of developing diabetes.[54]

- A 5 mm Hg drop in blood pressure makes a significant difference in outcomes.[52]

- 15-30 minutes of brisk walking daily can lower heart disease risk by 10%.[52]

- When the major health protective behaviors are evaluated, few Americans are ever found to be following them. Only 3% of American adults meet the 4 key goals of being a nonsmoker, being physically active, being at a healthy weight, and eating 5-plus servings of fruits and vegetables a day.[55] Focusing on any one of those 4 items can make a big difference in overall health.

Research also suggests that changing just one behavior may have a positive influence on many others,[56]so don’t underestimate the power of even the shortest PHP.

- Use SMART goals

Creating a SMART goal can happen fairly quickly, and SMART goals are excellent additions to a PHP. “SMART” stands forSpecific, Measurable, Action-Oriented, Realistic and Timed. SMART goals are featured heavily in many VA programs. For a quick overview, refer to the SMART Goals section of the El Paso VA Health Care System website. You can also refer to “How to Set a SMART Goal.”

- Make good use of follow-up visits

If you see a person regularly, consider discussing a different component of the Circle of Health each visit, at least briefly. For instance, a self-care topic can easily become something you discuss while you conduct a physical examination. Even if certain areas of the Circle of Health are not closely linked to the specific work you do, simply asking how it is going for them with implementing their PHP can be valuable. Continuity makes a significant contribution to a therapeutic relationship.[57] - Make use of shortcuts

Use Whole Health Education materials, Veteran handouts, and CPRS templates or forms to save time. Arrange it so different people on your team can help them with different skills. Different members of a Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) can teach breathing exercises, some gentle stretches, or how to do therapeutic journaling, for example. Unless you have a lot of time, you cannot and should not try to cover every area of the Circle of Health in one visit. Typically, it works best to choose just one area of focus.

- Take advantage of the team approach

Whole Health Care is not a solo endeavor for any one clinician, even if they know the patient best and see her or him the most. Have the patient decide who will be on his or her Whole Health team. That includes health care professionals, and it also includes loved ones who can offer support. Remind the Veteran that the PHP travels with him/her. It keeps evolving as a Veteran moves through the system.

THE FIVE-MINUTE PERSONAL HEALTH PLAN (PHP)

You can cover a lot of ground in a Whole Health encounter in just 5 minutes. Experiment with the following. It might help to take a family member, friend, or colleague through the process first.

- Take 1 minute to review the Personal Health Inventory (PHI).

- What is most salient to you?

- What does the Veteran care about most?

- What are his or her key values?

- Take 1 minute to think about the person’s Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP). In one sentence, how would you summarize that?

- Take 1 minute to ask them which part of the Circle of Health they do best with, and which part they want to set a goal to improve.

- Take 1 minute to generate a simple SMART goal. You can use the “How to Set a SMART Goal” tool.

- Use the remaining time to discuss follow up.

- When will they check back in with your or another team member?

- What additional information do they need? (E.g., handouts, websites, taking a skill-building course)

- Who else would be helpful? Do you need to make some referrals?

- How can their family and friends support them?

VA colleagues who have been using the Whole Health Approach for the past several months/years will tell you that it is entirely possible to spend 10 to 15 minutes on creating a PHP and feeling it was done well, with compassion, good communication, and engagement. And a patient does not have to start from scratch at every visit. They may only complete a PHI once a year or so.

Experiment! Even if there is a time investment up front as you are first learning, the benefits are well worth it. One of them is being able to feel more fulfilled with your work.

Tip #10. Model Healthy Behaviors Yourself

One of the most fundamental elements of therapeutic presence is modeling healthy behaviors yourself. This doesn’t mean you have to do everything perfectly, but it does mean you should be able to speak about self-care approaches and CIH from personal experience. The overview, “Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care” delves into why self-care in a clinician’s life has such powerful effects for clinicians and patients alike, and offers an array of tips on how to do it.

Applications In Telehealth

With the Covid-19 pandemic, the V adapted to limitations on face-to-face contact with the expansion of virtual visits. Following increased patient interest in virtual visits, which improve access for patients with transportation issues or long commutes to clinic, the VA has decided to continue offering virtual care for the foreseeable future. For many clinicians, this shift away from in-person contact has complicated the process of establishing a therapeutic presence. After all, physical connection is one of the easiest ways to demonstrate a provider's desire to connect with a veteran and understand their perspective. Yet, even in the absence of hand-shakes, hugs, and physical exams, recent studies have shown that clinicians can establish therapeutic presence even in a telehealth setting. In fact, during Covid-19, they have sometimes created more personal connection, primarily due to shedding of personal protective equipment during video visits.[58]The recommendations below have been created by the Academy of Communication in Healthcare and are designed to facilitate human connection during telehealth visits. Academy of Communication in Healthcare

1. Since you are entering the patient's home environment rather than the sterile environment of a medical office, this facilitates a discussion of what matters to the patient. Begin the visit by taking more time to get to know the patient and resist the urge to immediately ask about the chief complaint. Telehealth psychology patients and providers have frequently noted that virtual visits can allow for a more trusting and open environment between the two parties by breaking down the vertical power dynamic of doctor and patient. In this more comfortable environment, patients may be more willing to discuss details about their personal life.

2. Remove barriers to a direct visual connection throughout the visit. This includes avoiding other online communication during the visit and maintaining eye-contact through the visit. Adjust lighting prior to the visit and ensure your face is visible through the meeting. Additionally, ask the patient if anything can be done to optimize audio or visual settings at the onset of the visit. You may notice that you are even more attuned to a patient's non-verbal cues in this setting because the focus is entirely on their faces.

3. Take time to set the agenda, and remember to focus on what matters most to the patient. The virtual encounter can already make a clinical interaction feel less legitimate, so it is especially important that you ensure that patients have addressed their needs by the end of the visit. Even if negotiation is required (using statements such as "Perhaps we could se up another visit to discuss this additional issue so that we can give it the attention it deserves"), patients will appreciate that you have acknowledged all of their concerns.

4. In the absence of physical connection, it is even more important to practice verbal communication skills that demonstrate empathy. The "PEARLS" mnemonic can provide you with some tools to convey empathy. PEARLS stands for partnership, emotion, apology and appreciation, respect, legitimization, and support. Legitimizing the patient's concerns is especially important in a virtual setting since it reiterates that you are in this together despite connecting from two very different locations.

In addition to these recommendations, many of the tips mentioned about for face-to-face visits can also be modified to fit a virtual setting. Telehealth has established a permanent place in clinical medicine, and providers who build meaningful relationships in a virtual setting will make a greater impact on their patients while also experiencing more personal satisfaction about these encounters.

Conclusion

This overview has explored 10 tips for enhancing your therapeutic presence. Using a process that parallels the Whole Health Approach, you are encouraged to choose one of these, set a goal (create your “Therapeutic Presence PHP”) and start working on that goal for a set period of time. Share what you are doing with a friend or colleague. Practice listening without interrupting. Do a loving kindness meditation daily. Meet with a mentor or role model. Take time exploring your own values and beliefs. Practice self-care. Experiment with the different tips you have received. You will not only have a more powerful therapeutic presence, but you will probably enjoy your work more too.

Author(s)

“Therapeutic Presence” was written by J. Adam Rindfleisch, MPhil, MD, (2014, updated 2021).