Recharge is different from other areas of self-care in the Circle of Health. Sometimes, rather than requiring that a person “do something,” enhancing Whole Health may involve not doing something. Recharge can involve taking a break, or a vacation. Of course, a major focus for Recharge in many Veterans’ Personal Health Plans (PHPs) is sleep, which is essential to good health. This overview builds on the material in Chapter 9 of the Passport to Whole Health, focusing on how sleep is influenced by all of the areas of the Circle of Health.

Key Points

- Good sleep has a multitude of health benefits; conversely, insomnia can be quite harmful to health and can contribute to decreased lifespan and risk of multiple chronic diseases.

- As you work with Veterans to help them improve their sleep, there are many options. Goals related to self-care, such as dietary changes or creating activity plans can help, as can working with stress using various mind-body tools, including those offered by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I).

- Professional care can also play an important role when it comes to Recharge. Dietary supplements (several are discussed), acupuncture, and pharmacotherapy all have their place, as do a number of other approaches.

Meet the Veteran

Carl, a 62-year-old retired Air Force non-commissioned officer, presents with complaints of poor sleep. His symptoms began when he took a job that required him to work night shift after he retired from active duty. He describes difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. He occasionally has disturbing dreams relating to his service in Operation Desert Storm. He has undergone polysomnography in the past, and it demonstrated mild obstructive sleep apnea, but he declined treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

He reports difficulty falling asleep unless he takes medication. He has tried multiple over-the-counter agents but feels groggy in the morning whenever he takes them. About three years ago, he was prescribed zolpidem 10 milligrams and initially found it to be effective. However, he has been using it essentially continuously for at least 18 months, and lately he has found it to be less effective. As a result, he has increased his dose to two tablets. His primary care physician has become concerned about the increased dose, and the pharmacist has expressed concerns about continued usage at this dose. Carl recently experienced a fall during a sleep-walking incident in which he sustained minor injuries.

Carl lives with his wife in a small single-family home. He spends his time doing woodworking in his home shop. He consumes at least 12 cups of coffee daily, noting, “We always keep a pot on during the day.” He usually watches TV in the evening, when he may drink one to three beers. He typically falls asleep briefly in his recliner. He is very concerned about local politics and spends at least an hour each evening on the computer doing social-networking and related activities. He has a variable sleep schedule and watches TV in bed until he dozes off, but he is often awakened by the television between 3 and 4 a.m. He used to be an earlier riser, but now he sleeps until 8 or 9 a.m., especially if he had a bad night of sleep the night before. He does not exercise regularly and has gained 30 pounds in the past year. He is often tired and irritable during the day. He feels depressed and states, “I wonder how it could ever have gotten so bad.”

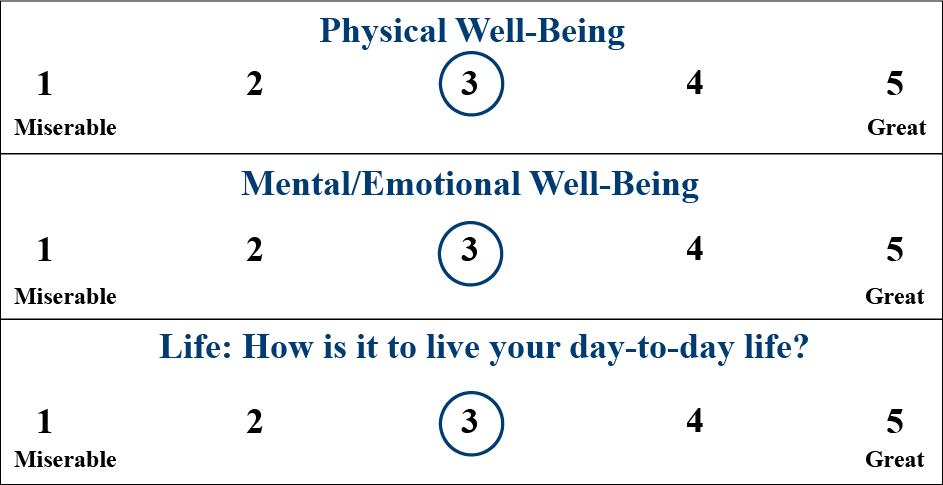

Carl is asked to complete a Brief PHI. His Vitality Signs are all in the mid-range:

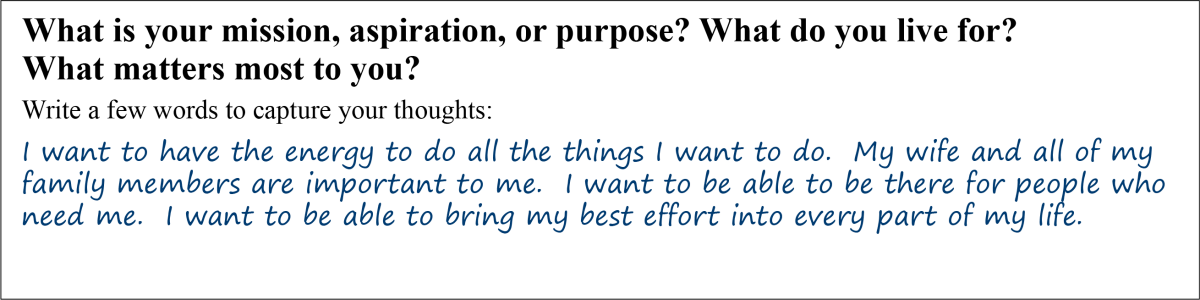

His Mission, Aspirations, and Purpose (MAP) answers focus on having enough energy to be there for his loved ones:

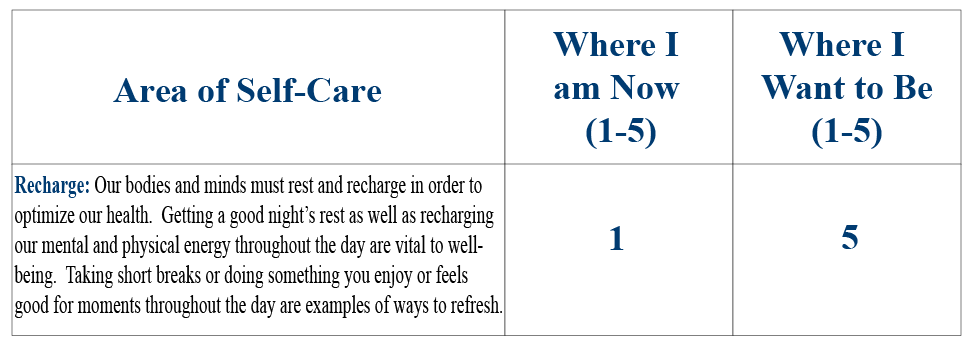

Carl has a variety of ratings for “Where I am Now” on the second page of his PHI. He makes it clear that sleep is where he wants to focus, though.

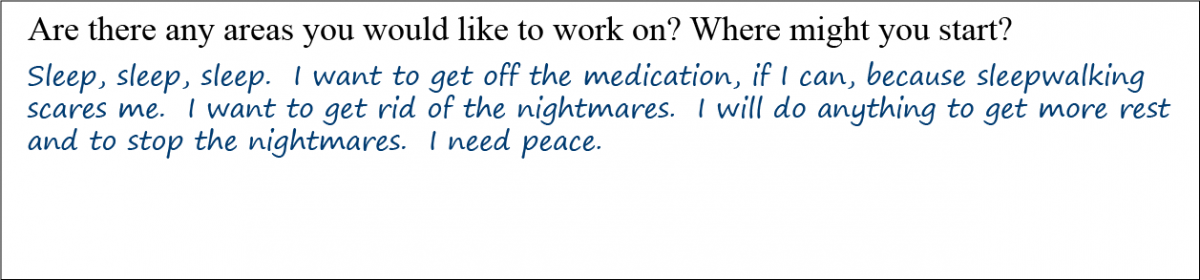

The final question on Andre’s Brief PHI is actually a great springboard into having a conversation with him about options.

Introduction

If there’s a secret to a good night’s sleep, it’s a good day’s waking.[1]

—Rubin Naiman

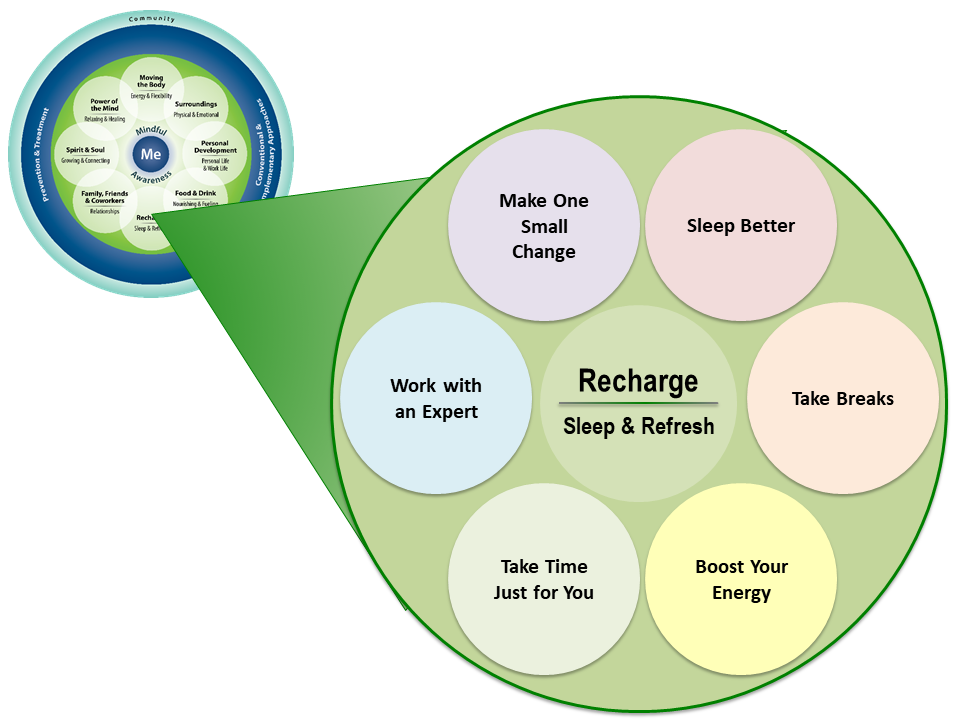

The purpose of this review is to build on Chapter 9, “Recharge: Sleep & Refresh” in the Passport to Whole Health. How is it possible to help someone like Carl find the peace he wants? In the Whole Health skill-building courses for Veterans, “subtopics” are provided to help them zero in on areas they could consider when it comes to creating their Personal Health Plans (PHPs). Figure 1 shows the subtopics for the Recharge circle.

This overview will focus on the “Sleep Better” and “Work with an Expert” circles, providing an evidence-informed examination of how VA providers can support Veterans with healthy sleep using the Whole Health approach. The incidence of sleep disorders in Veterans is higher than for the general population and is often associated with other comorbidities, including depression, suicide, and pain. A recent review showed that more than 40% of women Veterans have insomnia.[2] According to the National Veteran Sleep Disorder Study published in 2016, there was a six-fold increase in the prevalence of sleep disorders between 2000 and 2010. [3]

What is insomnia?

Insomnia is defined as inadequate sleep duration or nonrestorative sleep. In surveys, insomnia may be defined by questions such as, “Do you have difficulty falling asleep?” or “Do you have difficulty staying asleep?” In the sleep literature, insomnia is a term that often is used to describe long sleep latency; people with insomnia take longer to fall asleep, they have frequent awakenings, or both.[4] The most essential element in the care of patients with sleep complaints is the subjective data they provide, and the most commonly used research scale for subjective evaluation of insomnia is the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI)[5], which can be a useful part of the Whole Health Assessment when you are working with someone who wants to focus on Recharge.

Objectively, studies of people with insomnia show that they have modest increases in how long it takes them to fall asleep compared to people without insomnia. They spend more time awake during the night, and they have slight decreases in total sleep time when compared to controls.[6] In extreme cases, patients may complain of being awake when physiologically they are actually asleep. This is known as sleep state misperception.[6]

Types of insomnia

Insomnia can be grouped into three different types depending on the duration of the problem: transient, acute and chronic.

Transient insomnia

Transient periods of sleep disturbance associated with situational stress are a universal human experience. The annual incidence of transient situational insomnia is estimated to be as high as 85%.[4]

Acute insomnia

When insomnia persists more than a few nights, but less than a month, it is classified as acute insomnia. Severe acute insomnia is a significant risk factor for the development of chronic insomnia, but it is unclear if intervention in acute insomnia, including behavioral and pharmacological means, can reduce the risk of the development of chronic insomnia.[7]

Chronic insomnia

Chronic insomnia is defined as insomnia that persists for more than a month. Chronic insomnia affects an estimated 9% to 30% of the general population.[4], and 27% to 54% of military personnel and Veterans. [8]

Insomnia Complications

Cardio-metabolic disease

Chronic insomnia has been shown to be a risk factor for a multitude of cardio-metabolic conditions including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart-disease and stroke.[9][10][11]

Mood and depression

While irritability is a common complication of acute or short-term insomnia, insomnia can be a marker for more serious psychiatric illnesses. A prodromal period of insomnia is a robust predictor of incipient depression.[12] In patients with depression, insomnia is associated with a greater risk of relapse and a decreased response to treatment.[13] Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to significantly improve response rates to pharmacotherapy for depression and helps get at the root causes of it, as the patient and therapist work together to problem-solve around why sleep is poor and how it can be improved.[14] CBT-I is discussed more below.

Accidents

Insomnia is associated with 7.2% of all workplace accidents and 23.7% of the costs of workplace accidents, resulting in a combined yearly expense of $31.1 billion dollars.[15]

Suicide

In a study of sleep and suicide risk in Veterans, poor sleep quality was significantly associated with suicidal ideation.[16] It was reported in 39% of Veterans interviewed. “Short sleepers” were more likely to have attempted suicide in the preceding year. The combination of insomnia and alcohol use was particularly predictive of suicide risk. Another study showed that sleep disorder prevalence correlated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in military personnel than did depression or hopelessness. [17]

Self-Care and Sleep

Moving the Body

Physical exercise is an important tool for addressing multiple sleep-related issues, including insomnia. It has been observed to have multiple beneficial effects on sleep including decreasing sleep latency, increasing slow wave sleep, and delaying onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, possibly because it increases body temperature.[18] Since sleep quality as measured by the percentage of deep non-REM (slow wave) sleep declines with age, exercise may be a particularly helpful foundation for a self-care plan for insomnia that affects older patients.[19]

Physical activity during the day helps the mind-body unit transition into sleep at night.

A systematic review of the effect of exercise training in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems reviewed six trials involving 305 study participants aged 40 or greater.[20] All studies used the self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to asses sleep quality. Study participants were assigned to either moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or high-intensity resistance training. Those assigned to the exercise groups had improved PSQI scores and reduced sleep latency, but they did not differ in reported sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, or daytime functioning.

A Cochrane Review of physical exercise for sleeping problems in adults aged 60 or greater found only one study that met criteria for inclusion in the review.[21] In this research, study participants were randomized to either 16 weeks of moderate intensity endurance exercise (four 30-40 minute sessions per week of either brisk walking or low-impact aerobics) or a wait-listed control condition. Compared with people in the control group, those who randomized to exercise reported increased PSQI global sleep scores at 16 weeks (p<.001) as well as improved sleep quality and sleep onset latency.[22]

In a 2018 study assessing the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality, 2,649 people aged 45-86 years old were evaluated in a cross-sectional fashion. Greater amounts of physical activity and less sedentary behavior were associated with higher sleep efficiency and a lower likelihood of evening chronotype (being overactive in the evening). This paper even demonstrated that “weekend warriors” compared to predominantly inactive people, were more likely to have higher sleep efficiency. The authors did not find any associations between physical activity and sleep duration in this study. [23]

While many of these studies discuss the benefits of general aerobic activity on sleep quality, it is helpful to recognize some specific forms of movement have also been shown to support healthy sleep. Tai Chi is one such example. A 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis analyzed results from 11 trials, totaling 994 subjects. Practicing Tai Chi on average of 1.5 to 3 hours each week for a total of 6 to 24 weeks led to improved PSQI scores in both healthy individuals and those with chronic conditions (including fibromyalgia, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease). [24] In addition to Tai Chi, the practice of Qigong has been shown to improve sleep quality. One particular series of Qigong movements that has been studied in relationship to insomnia is called “Ba Duan Jin”, often translated as “Eight Section Brocade”. As explained in a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 trials (randomized controlled trials and prospective controlled trials), Ba Duan Jin Qigong was found to significantly improve PSQI scores, including significant improvements within the subscales of subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, sleep disturbance and daytime dysfunction. [25]

Another form of movement that has been shown to enhance sleep quality is yoga. In a pilot study of 20 individuals with chronic primary insomnia, an eight week intervention of daily yoga was associated with improvements in self-rated sleep efficiency and total sleep time, and decreases in sleep latency and wakefulness after sleep onset.[26] A randomized trial of yoga in 139 adults over age 60 who lived in the community evaluated several mental health indicators, including sleep. Yoga led to statistically significant improvements in all parameters, including global PSQI scores, rating of sleep latency, sleep efficiency and daytime function.[27] A systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 studies of yoga interventions involving 649 study participants found that while the studies were generally small and hampered by mixed methodological quality, yoga appeared superior to other more conventional physical activity interventions in improving general self-rated health status, aerobic fitness and strength. In addition, a significant improvement in multiple self-reported sleep measures, including improved PSQI scores, decreased sleep latency and increased sleep duration were reported.[28]

Refer to “Yoga” for additional information.

For most adults with sleep complaints, exercise is a useful element of a personal health plan (PHP). Given the low risk, low cost, and myriad of other health benefits of physical activity, it should be strongly recommended to all patients with sleep complaints as a part of a comprehensive approach.

SURROUNDINGS

The sleeping environment can have a major effect on sleep quality. One of the first-line interventions to promote healthy sleep is a collection of behaviors and suggestions related to the sleep environment, known as “sleep hygiene.” In 1971, Dr Peter Hauri coined this term and developed a set of “rules” based primarily on his clinical observations of patients with poor sleep. Since then, there have been countless variations on these rules and depending on the study different sleep hygiene practices are included. A few common sleep hygiene suggestions as they relate specifically to the sleep environment[29] include the following:

- Eliminate noise from the bedroom

- Maintain a regular bedroom temperature (not excessively warm, nor excessively cold)

- Eliminate bedroom clock

- Use bedroom only for sleep (ie, not as an office space or place to watch TV).

- Sleep in a comfortable bed

- Minimize light levels

The intention of these and other recommendations to be discussed in later sections is to avoid behaviors that interfere with a normal sleep pattern and engage in behaviors that are conducive to healthy sleep. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of sleep hygiene education on insomnia found that there was a significant improvement in sleep quality, though the effect size was small to medium. [30] While not all of the individual components of sleep hygiene have been studied in isolation, there are a few that have been found to be more supported by empirical data over time. In particular, the well-studied areas related specifically to the sleep “surroundings” include electronics usage and associated light exposure.

Allergens and sleep environment

Indoor air quality problems can result in respiratory allergies and, potentially, exacerbation of sleep-related breathing problems. While research is limited on this topic, it stands to reason that maintaining a dust-free and clean bedroom is important. The use of a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter in the bedroom can further ensure good indoor air quality. Ensuring fresh air in the bedroom by slightly opening a window can mitigate the effects of outgassing from furnishings and building materials, especially in new homes. Hidden sources of mold and other allergens, such as dust mites in carpets and old bedding, should be eliminated or thoroughly cleaned. Bedding should be as good-quality as possible and cleaned frequently.

Electromagnetic fields (EMFs) such as those generated by electrical appliances and home electronics can affect sleep in a dose-related fashion.[31] Animal studies have shown that EMFs in the 50 to 60 Hz range suppress melatonin secretion by the pineal gland.[32] For this reason, it is wise to minimize—and whenever possible, eliminate—electrical appliances and electronics in the bedroom. Electronic devices that connect to the alternating current electric supply of the home should be kept as far away from the head of the bed as possible. Instead of a plug-in clock radio on the bedside table, a small battery-powered electronic clock is preferable. In many cases, the clock can also result in behavioral activation due to clock-watching, so it is optimal for the clock to be moved across the room, as far away from the head of the bed as possible.

Appropriate timing of light exposure is essential for optimal sleep. The use of bright indoor lighting and electronic screens, televisions, computers, hand-held devices and smartphones during the evening can result in delayed sleep onset due to suppression of melatonin secretion.[33] Individuals with delayed sleep phase syndrome are particularly susceptible to this effect.[34] Melatonin suppression in the brain is most sensitive to blue spectrum light. This light is commonly produced by flat screens.[35] Technology to block the blue light, such as blue-blocking glasses or screens or the use of apps which decrease blue levels, should be considered if exposure cannot be eliminated. Avoiding suppression of melatonin secretion in the evening by bright light is an important step in self-care of healthy sleep, insomnia prevention, and treatment.

A cross-sectional study of 9,846 adolescents aged 16-19, evaluated the relationship between quantity of screen time (including television, computer, cell phone, tablet) and quality of sleep. Participants who had a total of four or more hours of screen time after school were more likely to have a sleep onset latency of 60 minutes or more. In addition, all daytime screen use of two or more hours as well as screen use within one hour before bedtime was significantly associated with a sleep deficit of two or more hours. [36]

Another study involving 855 hospital employees and university students assessed the association between in-bed use of electronic social media and sleep quality. Individuals who used even small amounts of social media in bed were found to have a shorter duration of sleep during the weeknights. Those participants who used social media for an hour or more in bed were also found to have higher levels of anxiety and insomnia. [37]

Strategies to Increase Endogenous Melatonin to Improve Sleep

- Ensure a dark environment for sleep. Shift workers, in particular, should use eye covers or extra curtains on windows to reduce light exposure.

- Avoid exposure to screens from computers, TVs, tablets, and cell phones before bed. The blue light they emit can inhibit melatonin.

- Keep all electrical devices (e.g. cell phones, clock radios, and computers) at least 3 feet from the head of the bed while sleeping. Avoid electric blankets.

- Eat vegetables and fruits. They contain the nutrient building blocks for melatonin production.

- Keep the sleeping environment cool.

Light therapy

While light from electronics at night may be detrimental to healthy rest, certain types of light at certain times of day may be helpful for improving sleep quality. This practice has been termed “light therapy.” A randomized controlled trial assessed the effect of bright light therapy on non-seasonal major depression and found that both light therapy alone and light therapy in conjunction with fluoxetine were helpful in decreasing depressive symptoms. Therapy included use of 10,000 lux intensity light for 30 minutes once daily for 8 weeks. [38] One meta-analysis of light therapy for older adults with cognitive impairment suggests there may be a small benefit from light delivered in a certain way. Specifically, the studies included in this analysis suggested that light intensity may range from 210-10,000 lux with morning exposure for a period of 1-10 weeks. [39]

POWER OF THE MIND

Each of us literally chooses, by way of attending to things, what sort of universe he shall appear to himself to inhabit.

—William James, 1842-1910

Mind-body approaches can be extremely helpful in addressing insomnia and can be foundational in developing a PHP that addresses insomnia and related conditions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is regarded as the gold standard for the treatment of insomnia.[40] It is important to acknowledge that cognitive behavioral therapy was once considered an alternative therapy. As the research has shown it to have superior results, it has moved into the mainstream therapy. This is particularly true in the VA, where it is widely available. CBT-I uses a combination approach to address behavioral and cognitive issues that interfere with sleep. From a behavioral perspective, interventions include sleep restriction, stimulus control, and relaxation.

- In sleep restriction, the goal is to temporarily limit the time a person sleeps (especially during the day) in order to increase the homeostatic sleep drive. This is something that anyone who has been chronically sleep-deprived (as in residency training) is intuitively familiar with.

- Stimulus control seeks to minimize the impact of behavioral stimulation on arousal mechanisms. Examples include using the bed only for sleep, removing electronic devices like televisions and hand-held devices from the bedroom, relaxation routines prior to bedtime, and removing the alarm clock from the bedside table to avoid clock watching. Sleep hygiene, discussed earlier, is linked closely with this.

Relaxation involves using various mind-body tools to more successfully attain a relaxed state that is more conducive to sleep. The cognitive component of CBT-I addresses beliefs or feelings about sleep that cause behavioral arousal and interfere with sleep. A good example is the tendency to exaggerate the effect of a bad night’s sleep on the following day, “If I don’t get to sleep, I’ll never get through tomorrow.” Another example is the emotional reaction that can occur with early morning awakening. Simply advising a patient that no one sleeps straight through the night and that awakenings are a natural part of sleep organization can help. Suggesting that they replace anger or frustration over their awakenings with gratitude for being able to spend the time in their sleeping area also might be of benefit.

CBT-I has been shown to be as good as or better than medications in short-term studies of insomnia; furthermore, patients treated with CBT-I continue to maintain and, in many cases, improve even further after the treatment is completed. In a systematic review comparing the effectiveness of CBT-I with standard sleep medications, CBT-I was noted to have more durable long-term benefits.[41] Another review found that CBT had a significant and larger positive effect on sleep quality in college students compared to sleep hygiene education and relaxation/mindfulness/hypnosis training. [42] One meta-analysis demonstrated that even CBT-I conducted via the internet (instead of in-person), may also yield salutatory effects on anxiety and depression associated with insomnia. [43]

Current data supports cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as one of the most effective nonpharmaceutical therapies available for promoting a healthier sleep-wake cycle.

One drawback of CBT-I is that it is not always easily accessible, though it is offered much more commonly through the VA than through other care providers. For more information about this and a number of other mind-body options for improving sleep, refer to, “Hints for Encouraging Healthy Sleep.”

Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” [44] By cultivating an awareness of a person’s relationship to various aspects of their health, mindfulness practices allow for the possibility of a shift from habitual (and perhaps unhealthy) ways of living to a different (perhaps healthier) approach to their life. So how might a mindfulness meditation practice facilitate a sleep pattern conducive to restfulness? One study suggests that the salutatory effects of mindfulness result from these practices increasing both moment-to-moment awareness as well as an attitude of acceptance/”letting go” when faced with situations or thought patterns perceived as stressful or challenging. [45] Garland, and colleagues propose that mindfulness acts on both physiological arousal and cognitive arousal, ie, both the physical/chemical shifts in the body that lead to increased wakefulness at bedtime as well as the worry/fear/anxiety thoughts processes that often follow physiological arousal. [46]

This approach to healthy sleep has been studied in a variety of populations. A 2016 randomized controlled trial used a 6-week mindfulness intervention called Mindful Awareness Practices (MAPs) and assessed its effect on older adults, average age 66.3 years). The MAPs group showed significant improvement compared to the sleep hygiene education (control) group in outcomes related to insomnia symptoms, depression symptoms, fatigue interference, and fatigue severity. [47] A systematic review of the 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) curriculum found that there was a significant increase in sleep quality. [48] A review of 6 randomized controlled trials of varied mindfulness-based interventions in cancer survivors suggested that preliminary evidence points to healthier sleep in this population, though more studies are necessary. [49]

When reviewing literature specifically assessing mindfulness-based interventions for insomnia, the evidence is similarly positive. Both MBSR and a modified 8-week MBSR plus CBT-I program entitled “Mindfulness Based Therapy for Insomnia” (MBTI) have been shown to be associated with decreased sleep latency and total wake time (time awake at night) as well as increased total sleep time (time asleep at night). [50] A 2016 systematic review of 18 studies related to mindfulness-based interventions for insomnia supported the hypothesis that mindfulness training may have a healthy influence on sleep quality. In fact, this type of intervention was shown to decrease insomnia severity and sleep disturbance in not only healthy individuals, but also those with chronic disease and older adults. [46]

Meditation involves focusing one’s awareness in a non-judgmental, non-striving way, on the present moment. This may supported by the use of a mantra, the breath, or something else that brings the mind repeatedly back to the present moment. This focused attention reduces activation of multiple neural pathways in the brain, allowing for more efficient transition into sleep.

MBSR was compared to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of chronic primary insomnia in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 30 study participants who were stratified by gender and then randomized in a ratio of 2:1 to either an eight-week MBSR intervention or pharmacotherapy (eszopiclone 3 milligrams nightly for eight weeks). Validated self-report measures such as the PSQI sleep diaries and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) as well as objective validated surrogates for sleep (wrist actigraphy) were used. A follow up subjective assessment was performed at five months. All study participants met criteria for diagnosis of insomnia. All sleep measures improved significantly (p<0.05) in both groups when baseline measures were compared to those taken at eight weeks post-intervention. However, the MBSR group was more likely to no longer have insomnia at the conclusion of the eight weeks and at five months than the pharmacotherapy group. Participants assigned to the MBSR group were much more satisfied with their treatment at five months as well.[51]

Finally, MBSR has been compared to CBT-I in a group of cancer patients with insomnia. The study was a randomized, partially-blinded trial involving 111 study participants. Sleep diaries and actigraphy were used to measure the primary outcome measures, which included sleep onset latency, time awake after sleep onset, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency. Secondary outcomes included self-rated sleep quality, sleep beliefs, mood, and stress. CBT-I was better than MBSR in the primary outcome measures, both immediately and at the conclusion of the eight-week programs, but the differences were not significant statistically (p<0.35). At three-month follow-up, MBSR was equivalent to CBT-I. Both groups experienced reduced stress and mood disturbance (p<0.001). Although the authors conclude that CBT-I is superior to MBSR in the treatment of insomnia, another interpretation of the data would suggest that the interventions are roughly equal.[52] This is important, because MBSR may be more available than CBT-I.

In summary, it would appear that multiple mindfulness-based interventions are valuable in the treatment of insomnia and that mindfulness can be an important part of a PHP. For more information, as well as tools that can be used in practice, refer to “Mindful Awareness” and “Power of the Mind” in the Whole Health Library.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Mindfulness Sleep Induction Technique

The majority of sleep onset insomnia is due to the intrusive thoughts of a racing mind. The next time you have trouble initiating sleep, give this a try:

Begin with abdominal breathing.

- Place one hand on your chest and the other on your abdomen. When you take a deep breath, the hand on the abdomen should rise higher than the one on the chest. This insures that the diaphragm is expanding, pulling air into the bases of the lungs. (Once you have this mastered, you do not have to use your hands).

- Take a slow deep breath in through your nose for a count of 3-4, and exhale slowly through your mouth for a count of 6-7. (Your exhalation should be twice as long as your inhalation). This diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the vagus nerve, which enhances the “relaxation response” Allow your thoughts to focus on your counting or the breath as the air gently enters and leaves your nose and mouth.

- If your mind wanders, gently bring your attention back to your breath.

- Repeat the cycle for a total of 8 breaths.

- After each 8-breath cycle, change your body position in bed and repeat for another 8 breaths.

It is rare that a person will complete 4 cycles of breathing and body position changes before falling asleep.

Guided imagery

According to the Academy of Guided Imagery, the term “guided imagery” refers to “a wide variety of techniques, including simple visualization and direct suggestion using imagery, metaphor and storytelling, fantasy exploration and game playing, dream interpretation, drawing, and active imagination where elements of the unconscious are invited to appear as images that can communicate with the conscious mind.” [53] For insomnia, it is often used to help a person relax more deeply. Since behavioral hyperarousal is a key contributor to the development and perpetuation of chronic insomnia, developing a greater capacity for relaxation can be helpful in improving sleep.

Guided imagery has proven useful as a self-care modality for improving sleep. In a study of 41 people with insomnia, subjects were randomized to one of three conditions: 1) no instructions, 2) general distraction, and 3) specific imagery distraction. The imagery distraction group rated their sleep onset latency as significantly shorter than the general distraction (p<0.05) or no instruction group p<0.01).[54]

Guided imagery audio programs are commercially available on CD and in MP3 form and can be utilized in a wide variety of settings to good effect. Guided imagery has been widely utilized within DOD and VHA to address posttraumatic stress in troops returning from deployment. It has been shown to be effective and widely accepted, and it is now a part of the “List I” group of complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches that will be covered by VA (for what indications and how often is not yet clear).

Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) is widely used as treatment for disabling nightmares in the setting of PTSD.[55] IRT helps practitioners to create detailed nonfrightening outcomes within common, recurrent nightmares. This therapy has been shown to be as effective as prazosin for decreasing nightmares, and when IRT is combined with CBT-I, studies have shown even greater treatment outcomes related to sleep quality and posttraumatic stress symptoms. [56] Under the direction of a trained therapist, the emotional impact of disturbing dream content can be dissipated.[57]

Guided imagery also has been shown to be effective in managing symptoms of fatigue. Patients with thyroid cancer undergoing radioactive iodine therapy listened to a guided imagery CD once daily for 4 weeks. When compared with the control group, symptoms of fatigue were found to be significantly decreased. [58] Similarly, patients with multiple sclerosis were found to have decreased fatigue with the use of guided imagery. [59]

In summary, guided imagery for sleep and posttraumatic stress can be an effective therapeutic approach to include in a PHP.

Breathwork

Conscious manipulation of breathing is a powerful psychophysiological intervention. It improves the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and it reduces behavioral hyperarousal.[60] One study showed that by practicing breathing at a rate of 6 breaths per minute for 20 minutes prior to going to sleep, participants were able to decrease sleep latency and number of awakenings, while increasing sleep efficiency. [61] Other key components to therapeutic breathing that have been shown to activate the parasympathetic nervous system and thus support easeful sleep include practicing abdominal breathing, as well as maintaining an inhale-to-exhale ratio of 1-to-2. [62]

Refer to “Breathing” for more information.

Yoga Nidra

iRest® Yoga Nidra (Integrative Restoration Institute www.iRest.us) is a secularized practice of yogic meditation. The practice involves the invocation of deep relaxation, attention training, the development of self-management tools, and learning to proactively engage emotions, thoughts, joy, and awareness.

iRest was initially piloted at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and is now widely available in military and VHA facilities. iRest has applications as a complementary approach in the treatment of PTSD, traumatic brain injury (TBI), chronic pain, chemical dependency, depression, anxiety, and sleep-related issues including insomnia, as well as for enhancing well-being and resiliency[63]. Large-scale trials of iRest are not yet available, but small case series have been presented. iRest has been embraced by the Veteran and military community.[64] The U.S. Army Surgeon General and the Defense Centers of Excellence (DCoE) recommend iRest for the management of chronic pain and PTSD in military and Veteran settings.

A pilot study of the effect of iRest® Yoga Nidra on sleep complaints and daytime sleepiness in clinicians in a military medical center demonstrated a trend toward improvements in waking somnolence, as measured by the Epworth Scale. It was also well-accepted.[65] Additional studies, utilizing wrist actigraphy to measure sleep parameters, are underway.[65]

iRest includes many aspects of rational-emotive and cognitive behavioral therapy, which are helpful for those experiencing sleep disorders and insomnia, including deep relaxation, stimulus control, and paradoxical intention. iRest can form a foundation for self-care management for a variety of stress-related problems including insomnia and chronic pain. iRest is highly suitable for delivery in a group setting. Refer to the www.irest.us website for more information.

Mind-Body Bridging

A pilot study of a brief mind-body intervention in Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sleep disturbance evaluated 63 Veterans with self-reported sleep disturbance. Study participants received Mind-Body Bridging (MBB) or an active sleep education (sleep hygiene) control. MBB is a novel and emerging form of awareness training that teaches various awareness skills to help the individual calm the mind and relax the body. In addition, MBB teaches a person to become aware of mind-body states that are characterized by a heightened state of self-centeredness, including rumination, contraction of awareness, and body tension. Interventions were conducted in two sessions, once per week. Multiple patient-reported outcomes were used. Sleep disturbance decreased in both groups. MBB performed significantly better not only in terms of sleep, but in terms of PTSD symptoms, which remained unchanged in the sleep hygiene group. Overall mindfulness increased in MBB, while it remained unchanged in the control.[66]

FOOD & DRINK

Foods can have significant impact on quality of rest. The “rules” of sleep hygiene (discussed in the “Surroundings” section above) also include recommendations related to type and timing of food and drink consumption. Examples include eating a light bedtime snack to avoid going to bed hungry. In addition, being intentional about caffeine, alcohol and nicotine consumption throughout the day also plays an important role in maintaining a healthy resting pattern. [29]

Caffeine has objective effects on sleep onset and sleep quality even in individuals without sleep complaints.[67] Caffeine half-life usually increases with age,[68] so amounts that may have been tolerated early in life may result in insomnia later.

Alcohol is often consumed in the evening in an attempt to self-medicate for insomnia. Although alcohol may result in a more rapid sleep onset, this comes at a cost of increased sleep disruption in the second half of the night. With repeated exposure to alcohol at bedtime, the sleep-promoting effect may wane while the sleep disruption in the second half of the night worsens.[69] This gradually results in hypersomnolence during waking hours.

Certain types of food and drink we consume may also lead to physical conditions with poor sleep as a secondary outcome. For example, many foods, such as chocolate, tomatoes, onions, fats, and alcohol, can reduce lower esophageal sphincter pressure and contribute to nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux, delaying sleep onset, and triggering awakenings.[70][71] . Being overweight or obese is linked to sleep apnea.

Drawing attention to the impact of foods, caffeine, and alcohol is an important component of building a PHP that promotes healthy sleep.

SPIRIT AND SOUL

Honoring one’s self by reflective writing can have meaningful benefits and can be helpful in developing a PHP. Setting aside a few minutes each evening to record personal observations, worries, joys, and pleasures can ease the burden of “racing thoughts” that interfere with sleep onset. Refer to “Therapeutic Journaling” for more information.

RECHARGE

Although recharging requires a healthy sleep-wake cycle, it does not stop there. It also requires that we take breaks from our work routine. For more ideas on how to incorporate short and long breaks Refer to “Taking Breaks: When to Start Moving, and When to Stop”.

With a good night’s sleep and appropriate use of breaks, it is easier to explore our personal work-life balance and keep fine-tuning it. For more information, refer to “Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources.

Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches

According to data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 45% of adults with insomnia symptoms had turned to complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches in the past year.[74] The 2002 NHIS found that 65% of those using CIH for sleep had tried at least one herbal remedy.[75] Many patients do not disclose their use of complementary therapies, so clinicians ask their patients about them. Clinicians should also have sufficient knowledge to help guide patients [76].

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy, the use of aromatic oils from plant compounds, has been studied as an insomnia intervention. It is low-risk and may improve sleep quality. In a single blinded, randomized crossover pilot study of 10 study participants with insomnia defined by a PSQI score of five or greater, either lavender oil or sweet almond oil (the control) was administered by a vaporizer during sleep. The results were confounded by some of the study participants turning off the vaporizer upon going to bed, but nonetheless, significant improvement in the primary outcome measure (PSQI) was seen in those who inhaled lavender oil.[77] In another study of patients hospitalized with ischemic heart disease, lavender oil aromatherapy was associated with statistically significant (p<. 001) improvements in self-rated sleep quality, as measured by a self-rating scale. In this study, a few drops of lavender oil were placed on a cotton ball on a bedside table about 20 centimeters from the sleeping study participant’s head.[78]

Dietary supplements: Nonherbal compounds

Supplements that may be beneficial for sleep include minerals, vitamins, botanicals, and precursors of neurotransmitters thought to be involved in the regulation of sleep onset.

Note: Please refer to the Passport to Whole Health, Chapter 15 on Dietary Supplements for more information about how to determine whether or not a specific supplement is appropriate for a given individual. Supplements are not regulated with the same degree of oversight as medications, and it is important that clinicians keep this in mind. Products vary greatly in terms of accuracy of labeling, presence of adulterants, and the legitimacy of claims made by the manufacturer.

Magnesium. Magnesium is an essential element that is often deficient in the standard American diet. Supplementation is well tolerated as long as renal function is normal and excessive accumulation does not occur. Magnesium has multiple physiological effects including sedative, anticonvulsant, antihypertensive and muscle-relaxant properties. Magnesium also may enhance the production of melatonin by the pineal gland.[79] Magnesium supplements are available in multiple formulations that differ mainly in terms of their likelihood of causing loose stools. Amino acid chelates of magnesium (chelated magnesium) are less likely to cause diarrhea. A typical dose is 300 milligrams two times daily.

Precautions: The first toxic side effect of magnesium is diarrhea. If this occurs, reduce the dose.

Vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 is a cofactor in synthesis of multiple neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin and melatonin. B12 deficiency can result in depression and other neuropsychiatric disturbances. B12 supplementation has been reported to improve insomnia in a variety of settings.[79] B12 deficiency can be diagnosed through direct measurement of serum levels. In the face of low normal serum levels, an elevated methylmalonic acid (MMA) level suggests biochemical insufficiency and can be used as a more sensitive test. Supplementation can be accomplished through oral or sublingual methylcobalamin tablets dosed at 1 milligram daily, although in severe deficiency a period of parenteral therapy with cyanocobalamin may be appropriate.

Precautions: B12 is adequately excreted in the urine and rarely causes side effects except in renal failure.

L-Tryptophan. L-Tryptophan is an essential amino acid found in foods rich in protein including eggs, dairy, chicken, fish, tofu, soy, and nuts. Some studies have shown that taking L-tryptophan as a supplement may lead to increased sleepiness and decreased sleep latency. The typical dose to assist with sleep is 1 gram taken 20 minutes before bedtime. [80]

Precautions: In 1989 a batch of contaminated L-Tryptophan caused eosinophilia myalgia syndrome. Since then, that has not been a concern with this supplement. The most common side effects include GI symptoms such as gas, reflux, nausea, and vomiting, as well as headaches or dizziness. There is also a potential risk for serotonin syndrome as L-Tryptophan increases serotonin levels in the brain. Consider using with caution when taking other medicines that increase serotonin levels. [80]

Melatonin. Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland in response to declining light levels. Its release is suppressed by light. It acts as the principal circadian signal transducer. Exogenous melatonin has been used for insomnia with varying results. A systematic review and meta-analysis of melatonin looked at 19 studies involving 1683 study participants with “sleep disorders”. Melatonin treatment significantly reduced sleep onset latency by 7 minutes, increase prolonged subjective sleep time by 8 minutes, and modest improvements in sleep quality. [81] Melatonin is especially effective in the setting of delayed sleep phase syndrome.[82] A review and meta-analysis of five trials including 91 adults and four trials including 226 children found that melatonin treatment advanced mean endogenous melatonin onset by 1.18 hours (95% CI 0.89-1.48) and clock hour of sleep onset by 0.67 hours (95% CI 0.45-0.89).

Melatonin is well tolerated; complaints of headache, nausea, and drowsiness have been noted by small numbers of study participants. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that timed use of melatonin for delayed sleep-wake cycle disorder, which often is the case in the people suffering from jet lag. [76]

Melatonin should be taken about 45 minutes before bedtime. The typical dose is 1-3 milligram(s), taken orally. Lower doses, such as 0.3 milligrams, may be more effective than higher doses. Sublingual tablets avoid first-pass metabolism and may be more effective than oral dosing.[83] Melatonin is now available through the VA Formulary.

Precautions: Short-term use of melatonin is generally well-tolerated. It can theoretically affect blood pressure as well as testosterone and estrogen levels. Long-term use may lead to increased risk of bone fractures, and thus it is likely best used in the short-term and on an as needed basis. [83]

Dietary Supplements: Herbal remedies

Herbs can be of benefit in addressing sleep complaints and insomnia. In contrast to pharmaceutical hypnotics, herbal remedies are generally free of significant respiratory depressant effects and generally have favorable toxicological profiles. Herbs have a widespread tradition of use, but rigorous well-controlled studies are generally not available for most herbs used for insomnia and sleep disturbances.[79] [84]

Kava kava. Kava is derived from the dried rhizomes of the shrub Piper methysticum, which is native to the South Pacific, where the endogenous population has used the herb medicinally for centuries. Clinically, it was initially described as having a calming and relaxant effect with no impairment of consciousness. In contrast to many herbs, the psychotropic effects of kava are well understood and are related to substances called kavapyrones or kavalactones.[85] Kavapyrones act centrally as skeletal muscle relaxants and anticonvulsants. Pharmacologically relevant actions include gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) channel modulation and weak direct GABA agonist activity. Although primarily used for anxiety, kava may be useful in treating anxiety-related insomnia.[86]

At this point, however, high quality randomized controlled trials have not yet been conducted to show a clear association between kava kava and sleep quality. [87] Potential benefits of kava in treating anxiety and depression must be evaluated in light of the risk of hepatic and neurological toxicity when used long term and in high doses. Because of reports of hepatic toxicity, kava has been withdrawn from the market in much of the world, although it continues to be available in the United States. Individuals who use kava should be monitored appropriately for hepatic toxicity via liver function testing.[85]

Precautions: High doses of kava for prolonged periods of time have been associated with hepatotoxicity and liver failure. For this reason, this supplement has been taken off the market in Switzerland, Germany and Canada. More common side effects are gastrointestinal-related. Extrapyramidal side effects are also possible.

Valerian. Valerian is derived from the dried roots of Valeriana officinalis, a small flowering shrub native to northern Europe. It has long been used for insomnia. Valerian is the herbal sleep remedy for which the greatest evidence base exists.[86] Valerian is recognized as being indicated for the treatment of insomnia and restlessness by the German Commission E. Pharmacologically, it appears to increase the availability of GABA in the synaptic cleft. Clinically, it seems to work best after 2-4 weeks of nightly administration two hours before bed. Dosage can be in the form of a tea made from 2-3 grams of dried herb or as an ethanolic extract at doses of 600 milligrams. Safety appears to be good with only mild adverse effects such as headache or morning grogginess reported in small numbers.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of valerian for sleep analyzed the results of 16 placebo-controlled clinical trials involving 1,093 patients.[88] While methodological problems and variability among the studies made comparison difficult, the available evidence suggests that valerian may improve sleep quality without producing side effects. Moreover, it may be uniquely suited for longer-term treatment of chronic insomnia. It may need to be taken for a few weeks before it takes effect.

Precautions: Prolonged use of valerian can result in a benzodiazepine-like tolerance, which requires a slow taper when discontinuing. It is best not to use valerian and benzodiazepines in combination. Common side effects include headache and gastrointestinal intolerance.

Chamomile. Chamomile is derived from a member of the Aster family, Matricaria recutita, and it is one of the most commonly utilized herbal remedies in the United States. It is usually taken as a tea and is thought to be beneficial for indigestion and nervousness. It may be helpful with insomnia. A randomized controlled trial of chamomile in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) suggested that it might be effective in treatment of mild to moderate GAD.[89] Chamomile occupies a place in English and United States herbal practice similar to that occupied by valerian in German practice. It is quite safe but can cause allergic reactions in people with allergies to other members of the Aster family, such as ragweed.

Precautions: The main side effect of chamomile is that it can trigger allergic reactions in some individuals.

Herbal Teas. Herbal teas are traditionally taken in the evening one to three hours prior to sleep. Widely available examples include “Sleepy Time,” a mixture of chamomile, spearmint and lemongrass and “Organic Bedtime Tea,” a combination of valerian, chamomile and passionflower, with licorice, cardamom and cinnamon added as flavorings. As with all teas, a single bag is usually steeped in a cup of hot water until the tea is brewed to taste.

Whole Medical Systems+

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Acupuncture is the most familiar component of TCM in the West. However, it is important to recognize that as a whole medical system, acupuncture is but one component in an approach that is inherently focused on lifestyle-based wellness and prevention practices. The theoretical basis for acupuncture is based on the concept of qi, a life force that is conceptualized to flow in channels or meridians in the body. The flow of qi in these meridians can be affected by insertion of fine needles at certain points on the body, thus helping correct imbalances that are postulated to result in physical or psychological symptoms. This conceptualization also includes neurohumoral mechanisms more consistent with current Western physiological models.

Acupuncture is widely utilized to support healthy sleep. In a systematic review of 46 randomized trials involving 3,811 study participants, acupuncture was shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of insomnia.[28] A Cochrane review of acupuncture for insomnia analyzed 33 trials with 2,293 participants[90]. Although acupuncture was associated with improvement in sleep measures, effect sizes were small, and the studies had methodological problems that limited their ability to draw reliable conclusions. Most recently, a systematic review assessing acupuncture’s association with sleep quality analyzed 30 studies involving a total of 2363 participants. Results showed that acupuncture improved Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores significantly more than placebo/sham as well as pharmacotherapy. [91] Refer to Passport to Whole Health Chapter 18, “Whole Medical Systems,” for more about TCM and acupuncture.

Homeopathy. Homeopathy is often used to treat insomnia. Homeopathic preparations are widely available over the counter, and homeopathic physicians often treat insomnia. According to a systematic review of homeopathy for insomnia published in 2010,[92] four RCTs comparing homeopathic medications to placebo have been published. All involved small numbers of patients, had high withdrawal rates, and were statistically underpowered. Nonetheless, a trend toward benefit was demonstrated. No RCTs of treatment by a homeopathic physician have been reported, but observational studies suggest a benefit. Refer to Passport to Whole Health Chapter 18, “Whole Medical Systems,” for more about Homeopathy.

Pharmacotherapy

In 2016, the American College of Physicians published a review of the literature related to pharmacological approaches to insomnia. The review, funded by the US Department of Health and Human Service’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, included 35 randomized controlled trials. Findings pointed to low-to-moderate strength evidence that eszopiclone, zolpidem, and suvorexant improved short-term sleep outcomes compared to placebo. Evidence for other commonly used prescription medicines including benzodiazepines, melatonin agonists, and anti-depressants was insufficient or low strength. [93] Other evidence does suggest that low dose trazodone may also be effective for both primary and secondary insomnia. [94]

Sleep medications may be useful for transient and short-term insomnia and may be helpful in preventing them from progressing into chronic insomnia. However, sleep medications have only modest effects compared to placebo.[95] When conventional zolpidem (Ambien) 10 milligrams and 4 doses of eszopiclone (Lunesta) were compared to placebo, only higher doses of eszopiclone (2.5 and 3 milligrams) led to statistically significant improvements in sleep. The magnitude of the difference, while statistically significant, was small. For example, for eszopiclone at a 3 milligrams dose, the difference was only about 7 minutes, and this was the largest difference for all the sleep medications and doses tested. The primary outcome measure, latency (time) to persistent sleep (LPS) improved with both eszopiclone 3 milligrams and zolpidem compared to placebo. However, it only reduced LPS by 15.9 minutes. Side effects were more pronounced in the higher dose eszopiclone and zolpidem treatment compared to placebo.[95] In fact, over 50% of the benefit of sleep medications is likely to be attributable to the placebo effect.[96]

The literature also points to several significant concerns about initiating pharmacotherapy related to medication side effects. The American College of Physicians review referenced above reported that potential harms of these medications can include: confusion, dizziness, memory loss, morning sedation, falls, fractures, and motor vehicle accidents. These medications are also associated with increased all-cause mortality. In addition, these pharmaceuticals often lead to tolerance and dependence. [93] These concerns are particular germane to the elderly population. [97] Other increased risks associated with these medicines include behavioral parasomnias (sleep walking, sleep-related eating, etc), worsening of untreated sleep apnea, and interactions with alcohol. All of these side effects must be considered in the risk–benefit analysis. A meta-analysis of sedative-hypnotic use in older people found the number needed to treat was 13 while the number needed to harm was 6.[96]

Back to Carl

After meeting with his VHA health care clinician, Carl came up with several specific changes that have had significant benefits regarding his sleep and overall well-being. First, he has reduced his caffeine intake by gradually switching to decaffeinated coffee. Second, he and his wife agreed to redo their bedroom. They gave the TV in the bedroom to a local homeless shelter and bought a new mattress and good-quality cotton linens. They ripped up the old wall- to-wall carpet and discovered beautiful oak floors beneath, which Carl was able to restore easily. They try to leave the bedroom window open a little for fresh air.

Carl decreased his television watching in the evening and has been able to avoid napping after dinner. Instead of spending time on the computer doing social media, he does his community activism in person. He used his woodworking skills to build raised beds for a community garden.

For a time, Carl had trouble doing without his sleeping medication, but then he found that an herbal combination containing valerian and other botanicals was a good substitute. He has cut out beer except when he bowls with his new friends in the bowling league he and his wife just joined. He limits himself to just one or two drinks.

Even if he has an occasional bad night, he gets up at 6:30 a.m. each morning and goes for a walk-jog. He has lost 15 pounds and feels “10 years younger.” His wife wants to take some yoga classes at the local YMCA, and he thinks he may tag along. He is planning to run in a charity fun run in the spring. He adds, “Although I am sleeping a lot better, it is about so much more than sleep. With these changes I feel like I am more in control of my health. In a real way, I feel like I have my life back.”

Whole Health Tools

Resources

- The National Sleep Foundation website

- Information about iRest® Yoga Nidra

- The Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.

- A tremendous resource for information on herbs and supplements. Mobile apps are also available. A subscription fee may be required.

- Online MBSR courses through the Oasis Institute at the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine

- Guided Imagery programing

- Guided Imagery programing, which can be streamed for free!

- University of Wisconsin Mindfulness Program guided practices including body scan, breath awareness, yoga, tai chi, and practices for children

Publications

- Insomnia by Rubin Naiman, PhD. In: Rakel D, ed. Integrative Medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:74-85. Excellent review of an integrative approach to insomnia.

- Healthy at Home: Get Well and Stay Well Without Prescriptions by Tieraona Low Dog, M.D. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2014. Chapter 4 “Calming the Nerves, Strengthening the Nervous System” offers the perspective of a master herbalist on insomnia and related topics.

Author(s)

“Recharge” was written by John W. McBurney, MD (2014) and updated by Vincent Minichiello, MD. (2018