For centuries, people have seen mind and body as being divided, or separate. This is not the case; research makes it clear that both influence each other in many different ways. This overview focuses on the mind-body connection and how it can be used in a Personal Health Plan (PHP) to enhance Whole Health. This overview builds on the materials from Chapter 12 of the Passport to Whole Health. The first part discusses the history of the mind-body connection. The second part describes a number of specific mind-body applications, many of which are offered within the VA, including psychotherapies, breathing exercises, biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, meditation, and imagery. Research regarding the efficacy and safety of these approaches is summarized, and practical tools and resources are provided to help clinicians more fully integrate these approaches into practice.

Key Points:

- Mind and emotions play a key role in health. Research in psychoneuroimmunology, neuroplasticity, epigenetics, and the placebo effect are beginning to elicit the many ways in which mind and body interconnect.

- Using a combination of practices to elicit the relaxation response can be extremely beneficial.

- Options include, but are not limited to, breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training, clinical hypnosis, imagery, biofeedback, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, arts therapies, and therapeutic journaling.

- Tailor choices of mind-body approaches to the specific needs and preferences of each individual patient. It can help to be familiar with the latest research for various mind-body approaches.

Meet the Veteran: Matt

Matt is a 35-year-old Navy Veteran who has been struggling for the past several years with depression, unexplained bowel difficulties, headaches, and PTSD. During his tour of duty, he suffered an injury and recovered well. Unfortunately, a fellow soldier was killed in the same event. On some nights, when he thinks about the past and “what he could have done,” he drinks too much alcohol. This is occasional, however, and his wife and family are less concerned about substance abuse than they are about his nightmares, low mood, and tendency to withdraw from his family at unpredictable times. Matt finds that he struggles with irritability when he first gets home from work. He feels guilty and upset about his behavior, after the fact, but he has difficulty letting go of the stress he experiences during the day.

Matt’s clinic team introduced him to Whole Health, and Matt agreed to complete a Brief Personal Health Inventory (PHI). Reviewing it helped them direct the conversation with him in several ways:

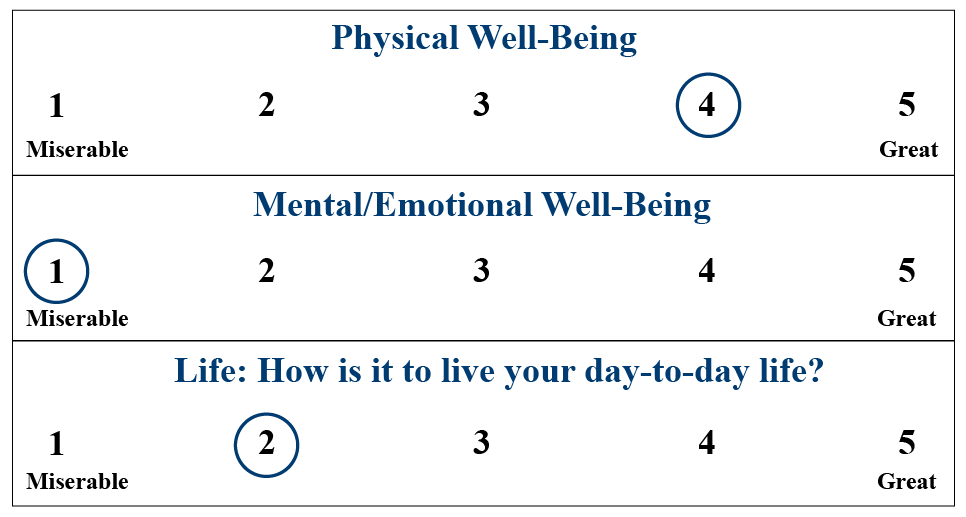

1. On his Vitality Signs, Matt feels he is doing much better physically than emotionally and in general.

He denies suicidal ideation, but he is worried about what could happen if he cannot find better ways to cope.

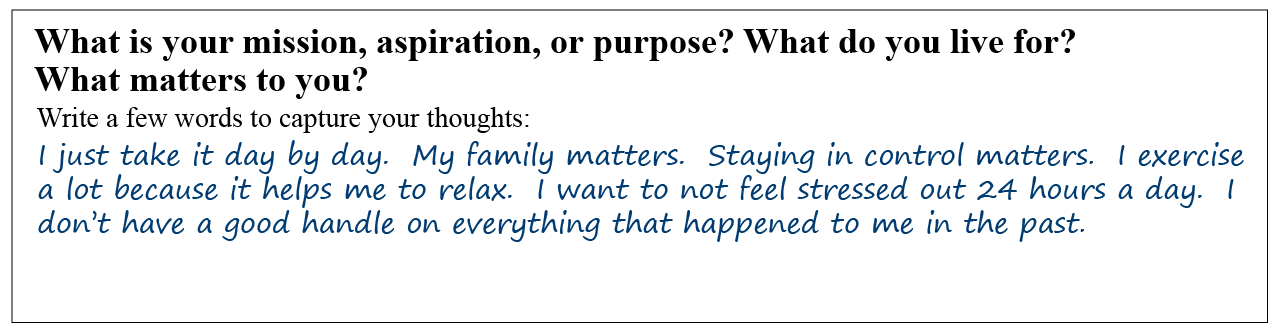

2. He would benefit from being able to take a little more time to go over the Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP) questions:

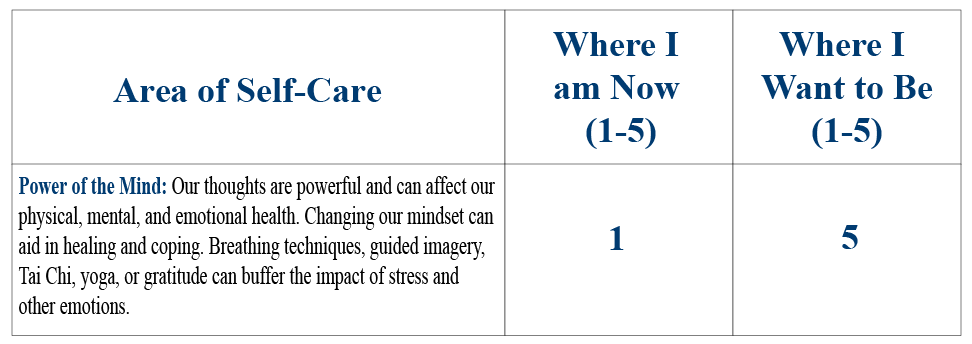

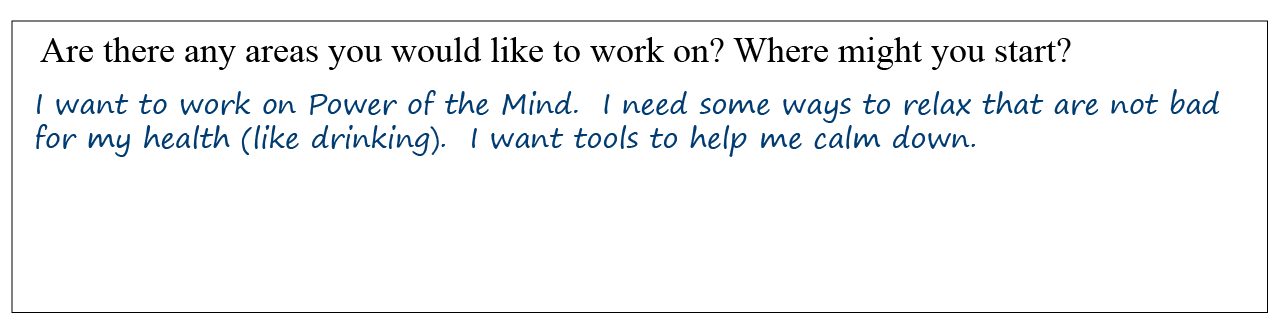

3. There is wide variation in his self-care ratings. For some, he seems to feel he is doing very well, but for others, there is a large discrepancy between where he is and where he wants to be. In it, he notes he is highly interested in focusing more on the Power of the Mind, as shown below.

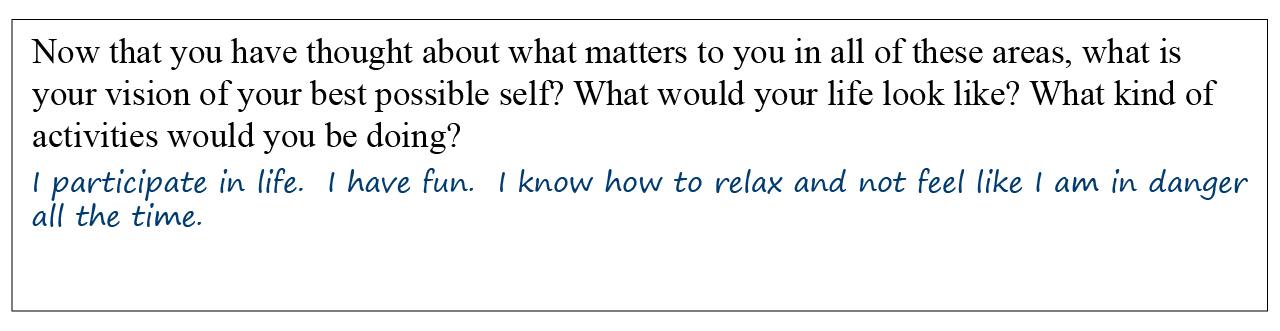

4. Matt’s final answers provide some initial guidance about what to discuss with him first. He makes it clear Power of the Mind is his highest priority.

What can you do to support Matt with his work on Power of the Mind? Fortunately, there are a number of options you can consider.

History of Mind-Body Connection

The idea that our mind and emotions play a critical role in our health dates back to Greek and Roman antiquity. The Greek and Roman forefathers of Western medicine viewed the mind and body as an integral whole. This connection was also found in Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine dating back more than 2,000 years. Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, believed that good health depended on a balance of mind, body, and environment. He considered patients’ environments and attitudes in his approach to treatment. He also believed in the body’s natural ability to re-balance itself, writing that “The natural healing force within each one of us is the greatest force in getting well.”

In the 17th century, Descartes’ philosophy of mind-body dualism was introduced. This model, which influenced the modern biomedical model of health and illness, emphasized the scientific study of the body in isolation, separate from the mind. Unlike the mind-body integration that was maintained in Eastern medicine, this development in the Western world led to the separation of the physical body from the mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. This resulted, in part, in a mechanistic and reductionistic orientation that continues to influence much of the modern biomedical model used today.[1] The separation of mind from body has led to many scientific gains, such as the discoveries of bacteria and antibiotics, as well as inventions, such as the stethoscope, microscopy, blood pressure cuff, and refined surgical techniques. Other levels of healing, however, have often gone unexamined and unaddressed.

The idea of a connection between the human mind and the physical body was first re-introduced at the end of the 19th century, as stress and mental states were increasingly considered to influence physical health. The work of George Beard, Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung, amongst others, introduced the concept that one’s mental life can have a profound impact upon physical health. Carl Jung, for example, said “The separation of psychology from the premises of biology is purely artificial because the human psyche lives in indissoluble union with the body.”[2] Interest in the power of the mind to affect physiological processes has grown during the past few decades, especially after Eastern healing approaches were introduced into Western medicine and culture. Increased attention has been placed on mind-body techniques, such as meditation practices and the importance of controlling thinking patterns related to oneself and one’s environment.[3] This has led to more value being placed in an individual’s active participation in his or her own healing through the development of inner resources.

Making use of the Power of the Mind requires a clinician to break out of the perspective of mind-body dualism that has been the focus of many health professionals’ training. Perhaps it is best not to become bogged down in terms of what constitutes mental health versus what constitutes physical health; the key is Whole Health, the health of the entire individual.

Placebo effect

Research studies began demonstrating the connection between the mind and body as early as the 1940s. Henry Beecher coined the phrase “placebo effect” after discovering in World War II that pain experienced by wounded soldiers could be controlled with saline injections.[4] The placebo effect has been widely studied and demonstrates that factors, such as expectation and suggestion, can have specific physiological effects on the body. Examples include intracellular repair of genetic mutations, cellular and antibody immune responses, wound healing, blood clotting, pain reduction and natural healing of infectious agents.[5] Placebo effects have been associated with both hypnosis and psychotherapy in general.[6] Research on the placebo effect indicates that it can be used to reduce pain,[7] improve sleep,[8] and relieve depression.[9] It can also ameliorate the symptoms of a wide variety of other conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),[10] asthma,[11][12][13] Parkinson’s disease,[14] heart ailments,[15] and migraine and other types of headaches.[16][17] These findings point to the importance of perception and the brain’s role in physical health.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH)

NCCIH’s mission is to explore complementary and integrative healing practices, as well as to disseminate information about them to the public. The 2012 National Health Interview survey reported that over 32% of US adults and nearly 12% of children are using complementary approaches.[18] NCCIH’s original scheme assigned complementary therapies into 5 different classes. It has since been changed to just 3 categories, but to stay consistent with past VA documents, the 5-category system is used here:

- Mind-body medicines are behavioral, psychological, social, and spiritual approaches that facilitate the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms. Included are such practices as meditation, biofeedback, hypnosis, imagery, art and dance therapies, relaxation therapies, breathing practices, etc

- Biologically-based practices are created from items found in nature such as vitamins, herbs, special diets, foods, and supplements.

- Manipulative and body-based practices include massage, chiropractic care, and reflexology.

- Energy medicine has as its base the belief that bodies have energetic fields that can be worked with to improve health and wellness. Examples of these practices include tai chi, Reiki and others such as therapeutic touch.

- Whole medical systems are healing systems that have been established over time, often in different cultures. Examples include Ayurvedic medicine, Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathic medicine.

For further information on NCCIH’s categories, please refer to the website. For additional information on the therapies listed above, as well as many others, refer to the “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part III: Complementary and Integrative Health for Veterans” and related Whole Health tools.

Recent advances in knowledge

Recent advances in the fields of psychoneuroimmunology, neuroplasticity, and epigenetics have provided a deeper perspective on how brains and physiology are interconnected, bi-directional, and able to change throughout life in response to experience. The mind and thought patterns not only influence mood and behavior, but also have a direct impact on physiology. They change neural connections in the brain, influence immune system functioning, make people more resilient to stress, and even affect the expression of genes.

Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)

Over the past decades, there has been extensive research demonstrating psychosocial influences on the development and course of various medical illnesses. The work of Robert Ader and others in the field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) has been instrumental in showing the bi-directional interactions between brain, behavior and the immune system. PNI represents a shift from the predominately biomedical paradigm towards establishing a biological basis for how the mind can influence the body through biological processes.

PNI research has recognized that the nervous and immune systems communicate through a common biochemical language that involves shared neuroendocrine hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, and their receptors.[19] It has been found that immune system health and physical health in general are influenced by psychological processes, including learning, psychological stress, emotions, and sensation, through neural and endocrine pathways. The immune system can selectively up- and down-regulate its responses under different conditions. For example, acute stress generally is associated with enhanced immunity, and long-term or chronic stressors are linked to suppressed immune function.[20] Emotional states can also influence immunological and inflammatory parameters.

Candace Pert’s research found that neuropeptides and neurotransmitters act directly upon the immune system, suggesting a mechanism through which emotions and immunology are deeply interdependent.[21] She asks, “Is the peptide first, or the emotion?”[21] One study found that experimentally induced negative mood is associated with suppression of the immune system, and positive mood is associated with enhancement of chemotaxis, a measure of immune function.[22] These relationships are especially relevant to immunologically-mediated health problems, including infectious disease, cancer, autoimmunity, allergy, and wound-healing.[23] Interestingly, patients with PTSD have been found to exhibit a number of immunological changes such as increased circulatory inflammatory markers, increased reactivity to antigen skin tests, lower natural killer cell activity and lower total T lymphocyte counts.[24]

In the past decade, the brain-gut axis has become an increasing focus of psychoneuroimmunological research. There is a growing volume of data to indicate that the immune system is a major communication pathway between gut microbes (complex ecosystem with a diverse range of organisms and a sophisticated genomic structure) and the brain, and may play an important role in stress-related illness.[25] Further understanding of the brain-gut axis has the potential to provide new areas for development for psychotropic medications.[26] Bidirectional relationships between the immune system, nervous system, and psychological processes likely exist in certain disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Stress can affect IBD, and IBD is associated with an increased risk of psychological difficulty.[27]

Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity, also known as brain plasticity, refers to the changes in neural pathways and synapses in the brain that occur throughout life as a result of changes in behavior, environment, and neural processes as well as through bodily injury.[28] The brain is no longer believed to be a physiologically static organ. Rather, research has shown that the brain’s physical structure (anatomy) and functional organization (physiology) alters in response to experience. A number of factors change neuronal structures and functions, including stress, adrenal and gonadal hormones, neurotransmitters, growth factors, certain drugs, learning, environmental stimulation and aging.[29]

Adult neurogenesis, the generation of new neurons in adult brains, is an interesting phenomenon of neuroplasticity. In a 2012 review article, Davidson and McEwen document how many forms of stress promote excessive growth in sectors of the amygdala, whereas effects on the hippocampus tend to be opposite.[30] They highlight the effect of specific interventions designed to decrease stress and promote prosocial behavior and well-being on brain structure and function. Additionally, a number of studies have linked meditation practice to differences in cortical thickness or density of gray matter. For example, participants trained to meditate over an 8-week period experienced increased left prefrontal cortex activation in their brain, an area associated with greater positive emotional states, deeper ability to concentrate, and stronger resilience following a stressful challenge.[31]

Research has also examined changes in brain activity before and after receiving cognitive therapy.[32][33][34] Meta-analyses have concluded that cognitive therapy for mood and anxiety disorders was associated with changes in brain regions consistent with neural models of affective regulation and self-regulation.[35][36][37] This suggests that cognitive therapy alters brain functioning associated with affect regulation, problem solving, and self-referential and relational processing. For example, Ochsner and Gross[37] found cognitive therapy to be associated with changes in regions that are involved in the regulation of negative affect, including the ventral and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and the right ventrolateral and inferior and frontal cortices.

Refer to “Mindful Awareness” and related Whole Health tools for information on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of meditation. Refer to “Recharge” for more information on neuroplasticity.

Epigenetics

Epigenetics describes heritable alterations in gene expression that do not involve DNA sequence variation and are changeable throughout a person’s life. Epigenetic research indicates that genes are dynamic in their expression and respond to physical stimuli such as stress, diet and exercise.[38] Epigenetics may inform why the pattern of aging is different between two genetically identical twins. In a 2016 review on epigenetics and aging, Pal and Tyler concluded that the human life span is largely epigenetically determined rather than being genetically predetermined. Diet and environmental influences impact life span through changing the epigenetic information.[39] A study published in the Journal of Psychoneuroendocrinology provides evidence that developing the mindfulness skill of maintaining a non-judgmental, open presence to the present moment without being carried away by thoughts, emotions, or perceptions can potentially influence gene expression. Kaliman and colleagues found that after 8 hours of mindfulness practice, meditators showed a range of genetic and molecular differences compared to nonmeditators, including altered levels of gene-regulating machinery and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory genes, which in turn correlated with faster physical recovery from a stressful situation.[40] The discovery that bodies and brains change throughout life in response to mental experience suggests that positive changes can be nurtured through mental training.

Research in epigenetics neuroplasticity, and psychoneuroimmunology make it clear that our minds and our bodies are not separate from one another. In fact, they are in a dynamic dance, constantly influencing one another. It is because of this changeability that mind-body approaches can bring about changes for people.

Mind-Body Applications

The remainder of this overview focuses on those practices generally included under the category of “Mind-Body Medicines” by NCCIH, as well as some other well-documented interventions that also utilize the power of the mind. Following an introduction to mind-body applications, there will be reviews of the literature on 13 different techniques as well as ways in which to incorporate them into your practice, when appropriate. The 13 techniques are divided into 2 categories: Relaxation Strategies and Emotional Healing Strategies.

It is possible to adapt, interweave, and integrate core mind-body principles and certain mind-body techniques in the course of a regular office visit.

Introduction to mind-body applications

Mind-body techniques offer patients the following:

- Greater control with their treatment

- Cost-effective therapeutic alternatives

- Effective options for managing chronic conditions and psychological disorders

- Methods for maintaining wellness.

John Astin conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses of research on mind-body techniques and found there is considerable evidence of efficacy for several mind-body therapies in the treatment of multiple health problems. These include coronary artery disease, headaches, insomnia, incontinence, chronic low back pain, cancer-related symptoms and cancer treatment-related complaints, as well as for improving post-surgical outcomes.[41] There was moderate evidence of efficacy for mind-body therapies in the area of hypertension and arthritis. Considerable evidence also exists for the effectiveness of mind-body therapies for the treatment of psychological conditions.[1] For example, refer to the overview “Depression,” the Whole Health tool “Depression,” “ and “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).”

In March 2011, the Defense Center of Excellence published Mind-Body Skills for Regulating the Autonomic Nervous System: Defense Centers for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury.[42] Admiral Mike Mullen, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Guidance for 2011, stressed the need for a “holistic” approach to caring for service members and their families. This report indicates that incorporating an assortment of mind-body approaches for regulating the autonomic nervous system may be more effective than just using one mind-body skill on its own.

The Mind-body Skills for Regulating the Autonomic Nervous System report also highlights that an especially promising use of mind-body skills is in the area of PTSD recovery. An important component of healing from trauma is to learn how to regulate physiological arousal in response to reminders of the trauma and ongoing life stressors, to effectively regulate affective arousal, and to learn to be more present in day-to-day experiences. The new VA-DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines for PTSD recognizes the benefit of many mind-body modalities as ways to augment other treatment approaches of PTSD symptoms, particularly with symptoms related to hyperarousal. Mind-body Skills for Regulating the Autonomic Nervous System notes that many approaches show promise for treating a variety of disorders, including anxiety, depression, headaches, chronic pain and insomnia.[42] It is noted that there is also substantial research indicating specifically that mindfulness meditation practices are effective for decreasing depression, anxiety, panic disorders, and substance abuse, among other problems.

Kim and colleagues reviewed the literature regarding mind-body practices for PTSD.[43] They included practices that are covered in this module such as meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Overall, they found that mind-body practices were a viable intervention for improving many PTSD symptoms, including intrusive memories, high-arousal states, and avoidance.

Relaxation Strategies

Extensive research indicates that relaxation therapies can beneficially influence the physiology of the body, reducing stress and boosting mood. Strong evidence supports

employing relaxation therapies to address a variety of medical and psychological difficulties. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program defined relaxation techniques as the following:[44]

…a group of behavioral therapeutic approaches that differ widely in their philosophical bases as well as in their methodologies and techniques. Their primary objective is the achievement of nondirected relaxation, rather than direct achievement of a specific therapeutic goal. They all share two basic components:

- Repetitive focus on a word, sound, prayer, phrase, body sensation, or muscular activity.

- The adoption of a passive attitude toward intruding thoughts and a return to the focus.

These techniques induce a common set of physiologic changes that is the opposite of the fight-or-flight response, which results in decreased metabolic activity, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and slowed brain waves. Relaxation techniques may also be used in stress management (as self-regulatory techniques)

Stress and the relaxation response

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) includes the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. It is responsible for the unconscious regulation of internal organs and glands. The sympathetic branch is responsible for up- and down-regulation of many body functions. Most notably, it mediates the fight-or-flight response, which arises when the body experiences stress (i.e. challenges or threats that lead to adaptive demands). Hormones are released, pulse and breathing rates increase, and blood vessels narrow in the parts of the body that are not needed to take action in an emergency. However, if the body remains in a stress state for a long time, emotional or physical damage can occur. Parasympathetic activation (sometimes referred to as the “rest and digest” or “feed and breed” response) is used to minimize the physiological response to stress.

Herbert Benson, a cardiologist and mind-body medicine pioneer, examined the physiological and psychological effects of Transcendental Meditation® (TM) on TM practitioners.[45] One of his most interesting findings was that the TM practitioners activated the parasympathetic branch of the ANS during their meditations. He described this phenomenon as the “relaxation response.” It is the body’s natural state of relaxation, as opposed to the state of hyperactivity of the nervous system associated with the fight-or- flight response.[46] Benson went on to publish additional results that indicated mind-body practices such as meditation, yoga, autogenic training, and hypnosis all elicit the relaxation response. As such, they decrease oxygen consumption, respiratory and cardiac rate, and muscle tone, while increasing alpha rhythm brain activity and skin resistance.[47]

Research has shown that regular elicitation of the relaxation response can result in the alleviation of many stress-related medical disorders.[48] It can work to counteract the harmful effects that chronic stress can have on our bodies due to the exposure to fluctuating or heightened neural or neuroendocrine responses. The relaxation response has been found to be effective for the following:[48]

- Anxiety

- Mild and moderate depression

- Anger and hostility

- Insomnia

- High blood pressure

- Premenstrual symptoms and menstrual cramps

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Functional bowel disorders

- Chronic pain

- Temporomandibular joint disorder.

Eliciting the relaxation response has also been found to be effective, at least in part, in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias, postoperative anxiety and pain, the side effects of cancer treatment, as well as in preparation for procedures and diagnostic tests.[48]

1. Breathing techniques.

Breathing techniques are also known as rhythmic breathing, deep breathing, abdominal breathing, or diaphragmatic breathing.

Technique. Andrew Weil, M.D., is an internationally known integrative medicine physician who has promoted the use of breathing techniques for health. He states on his website, “Practicing regular, mindful breathing can be calming and energizing and can even help with stress-related health problems ranging from panic attacks to digestive disorders.”[49]

Breathing techniques are considered mind-body interventions within complementary medicine and are used commonly for a variety of medical problems. For example, in the National Health Interview Survey of 2007, it was found that 24% of the adults surveyed with severe headaches/migraines, as well as 19% of adults with neurological conditions, used deep breathing exercises.[50]

Clinical applications. In some breathing techniques, the goal is to deepen the breath. Deep breathing is marked by expansion of the abdomen rather than the chest when breathing, as opposed to shallow breathing. Shallow breathing, also known as thoracic or chest breathing, is the drawing of minimal breath into the lungs, usually by drawing air into the chest area using the intercostal muscles. When the lung expansion occurs through movement of the lower body, breathing is typically referred to as “deep.” Movement of the abdomen with inhalation is seen or felt in deep breathing. In shallow breathing and higher lung expansion of rib cage, this is typically not present.

Shallow breathing can often accompany psychological difficulties such as anxiety, panic attacks, and stress. This is typically a result of sympathetic nervous system hyperarousal, often referred to as the fight-or-flight response. One way to promote parasympathetic dominance is with the use of slower, diaphragmatic breathing. This can be easily taught to patients during a visit.

Evidence. Breathing techniques are portable, easy, and safe. They are an economical way to practice relaxation. Practice in breathing techniques utilizes awareness of breathing rate, rhythm, and volume. According to the NCCIH,

Deep breathing involves slow and deep inhalation through the nose, usually to a count of 10, followed by slow and complete exhalation for a similar count. The process may be repeated 5 to 10 times, several times a day. [50]

There are many other useful techniques, which can be adjusted to the comfort of the individual user. For more information, refer to “Breathing.”

Often, breathing is not used as the sole intervention. It may be combined with other techniques including biofeedback, hypnosis, imagery and other relaxing strategies. In many forms of meditation, practitioners direct their attention to some intentional process like the breath.

Research has shown that decreasing breathing rate can aid in lowering blood pressure. The Food and Drug Administration has approved a relatively simple respiration monitor that facilitates slowing one’s breathing rate for the reduction of blood pressure.[51] A review of research on several specific breathing techniques found a trend toward improvement in asthma symptoms; however, the authors felt that this was not significant enough to draw reliable conclusions.[52] Breathing exercises and/or breathing retraining have been used with hyperventilation as well. A review of 7 randomized controlled trials found a trend toward improvement in symptoms with breathing techniques but not enough evidence for firm conclusions.[53] With painful conditions, breathing practices can serve both as relaxation and a distraction away from painful sensations. In one review, Anderson and Bliven found moderate evidence for the use of breathing for the treatment of chronic, non-specific low back pain, as well as for improving quality of life.[54] Another study suggests that it was only when breathing practice was combined with relaxation that it was found to benefit the individual with chronic pain.[55]

A recent meta-analysis focused on the efficacy of using breathing exercises to improve post-operative functioning and quality of life in patients with lung cancer.[56] The researchers found that breathing exercises may significantly improve both pulmonary functioning post-surgery, as well as improve quality of life for lung cancer patients. Techniques utilized included teaching controlled breathing by allowing slow, even breaths on the inhale and having an extended exhalation through pursed lips (like blowing out a candle).

Refer to “Breathing” for more information.

Try It for Yourself: Breathing Techniques

- Abdominal breathing. Take a minute or two to practice breathing in by expanding the belly outward. Let the belly expand on the inbreath before the chest does. The shoulders should not have to move. Take 10 slow, deep abdominal breaths.

- The 4-7-8 breath. Widely taught by Dr. Weil, this breath involves breathing in for the count of 4, holding the breath for the count of 7, and exhaling for the count of 8. You can adjust the speed of each breath based on how fast you count. When a person does this for the first time, they should do it seated or lying down and only for a few breaths, as it can make some people fell a bit giddy or light-headed. This is an easy technique to teach patients.

2. Progressive muscle relaxation

Technique. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a technique that has been extensively researched. It was developed by Edmund Jacobson in the early 1920s to monitor and control the state of muscle tension in the body. He wrote several books on the subject and claimed that anxiety is caused by skeletal muscle contractions.[57] In its original form, PMR taught relaxation of approximately 30 different muscle groups. The technique was shortened by Bernstein and Borkovec in 1973 and has been abbreviated even further today for use in clinical practice.[58]

Clinical applications. PMR is typically taught as a two-step relaxation practice to reduce stress and build awareness of sensations of tension and deep relaxation in 14 muscle groups.

- The first step in the PMR practice is to create tension in a specific muscle group, noticing what tension feels like in that area.

- The second step is to then release this muscle tension and begin to notice what a relaxed muscle feels like as the tension drains away.

By moving through the body, alternately tensing and relaxing different muscle groups in a certain order, one gains skill at recognizing and differentiating between the associated feelings of a tensed muscle and a completely relaxed one. When muscle tension is reduced, pain decreases.[59] When PMR is first taught, it is often recommended to create tension and relaxation several times in the same muscle group. With each contraction and release, muscle tension decreases further. Body awareness is enhanced, and relaxation is deepened. Through repetitive practice, a person can then induce physical muscular relaxation at the first signs of physical tension that accompanies stress. After the practice, there may be one or two areas that a person finds is still tense, requiring the need to go back over that area or muscle group to tense and relax one or two more times. Refer to “Progressive Muscle Relaxation” to learn more about this technique and how to teach it to your patients.

Evidence. PMR was originally used to treat symptoms of anxiety, but more recently it has been found to be effective for treating a wide variety of clinical conditions. It has been extensively studied for treatment of insomnia and headaches. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine concluded, based on 17 studies, that PMR was 1 of only 3 nonpharmacologic treatments empirically supported for treatment of chronic insomnia. It has been shown to help relax the body and mind at bedtime, allowing one to fall asleep more easily and to have a more restful night’s sleep.[60] It also has been found helpful in managing chronic neck pain.[61]

- A meta-analysis of 29 studies of the use of PMR for a variety of conditions found PMR to be an effective treatment for tension and migraine headaches and tinnitus.[62][63] It also improved tolerance of cancer chemotherapy.[62] There is also evidence that PMR is an effective treatment in reducing psychological distress in cancer patients and improving well-being in patients with inflammatory arthritis and IBS.[64][65][66]

- PMR can be readily adapted to minimize the risk of triggering pain in injured or painful areas. A person can simply avoid tensing up those specific areas of the body. Another adaptation of PMR is progressive relaxation (PR), which includes sequential relaxation of muscles, without muscle contraction. This is helpful for individuals that find the muscle tightening process of PMR difficult due to their specific health problems, such as recent surgery, pain, fibromyalgia, etc. PR is preferred by some people because they find it uncomfortable to contract muscles that are already tense.

- Refer to “Progressive Muscle Relaxation” and “Progressive Relaxation” for more information.

3. Autogenic Training

Technique. Autogenic Training (AT) is a relaxation technique developed by the German psychiatrist Johannes Heinrich Schultz in 1932. Autogenic means “generated from within.” AT is considered a form of self-hypnosis. It involves a series of simple, self-instructed mental exercises to increase relaxation without having to go through a hypnotic induction performed by a clinician. It is a technique recommended when stress is a contributing factor in producing or maintaining health issues.[67]

Clinical applications. More specifically, the practice of AT involves thinking several specific phrases to oneself to produce a relaxed feeling of warmth, heaviness, and emotional calm throughout the body. These phrases are stated silently to oneself in a non-striving, detached way, which fosters the parasympathetic quieting of the body (the relaxation response). At the core of AT is a set of standard exercises which focus on six physical manifestations of relaxation in the body:

- Heaviness in the musculoskeletal system

- Warmth in the circulatory system

- Awareness of the heartbeat

- Slowing down the breath

- Relaxing the abdomen

- Cooling the forehead

These exercises build weekly, starting first with relaxation of the peripheral extremities. Next, regulation of the heartbeat and breathing patterns is included. Lastly, relaxing the stomach, cooling the forehead, and feeling overall peace in the mind and body are added. Not all individuals using AT will experience all these sensations. Instead, they may report the overall effects of relaxation, such as reduced heart rate, lessening of muscular tension, slower breathing, reduced gastrointestinal activity, improved concentration, lessened irritability, improved sleep, and more.[68]

Try It for Yourself: Tune in to Your Body

Try feeling each of the six Autogenic Training manifestations as you read through this. If you have difficulty, start by just focusing on one specific part of the body, like your hands.

- Musculoskeletal system. Allow yourself to feel heaviness in the muscles and bones. Can you tune in to specific bones or muscles?

- Warmth. Focus on blood flow. It might help to focus on your hands or feet at first. Can you make them warmer?

- Pulse. Can you tune in to your pulse? Where do you feel it?

- Breathing. Note your respiratory rate. Take a few slow deep breaths to slow it down, as you feel comfortable.

- Abdomen. Imagine your abdomen softening, like melting snow. Feel the breath in the abdomen, as you practiced in the breathing exercises, above.

- Forehead. Allow your forehead to cool down. You might imagine an ice cube melting on it, or a gentle breeze blowing across it.

Evidence. Empirical data supports the effectiveness of AT. In a meta-analysis of 60 studies, Stetter and Kupper found significant positive effects of AT treatment when compared to controls for clinical outcomes for a number of diagnoses, including the following [67]:

- Tension headache

- Migraine

- Mild-to-moderate essential hypertension

- Coronary heart disease

- Bronchial asthma

- Somatoform pain disorder (unspecified type)

- Raynaud’s disease

- Anxiety

- Mild to moderate depression

- Functional sleep disorders

Krampen demonstrated that patients receiving both AT and cognitive therapy for treatment of moderate depression showed the best outcome at follow-up.[69] AT has been found to be useful in the treatment of IBS by enhancing self-control.[70] It can also been used as an important adjunct in reducing symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease.[71] AT can be considered a helpful adjunct to other types of treatment for mood and anxiety disorders, such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy or psychopharmacological treatment.

Refer to “Autogenic Training” for more information.

4. Hypnosis

Technique. The term hypnosis comes from the Greek word hypnos which means “to sleep.” Hypnosis has been used in medicine for millennia, with ancient texts from Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome all describing practices that are considered hypnotic. In the late 1700s, hypnotism was led out of the realms of the occult into scientific study with the work of the Austrian physician, Franz Mesmer, to whom we owe the word “mesmerism” and its derivative “mesmerize.” In the 20th century, Milton Erickson revolutionized the practice of hypnosis, and the vast majority of clinicians practicing hypnotherapy today use some form of the Ericksonian approach.

Erickson viewed hypnosis as a method of calming and quieting the conscious mind so that one could access and work directly with the subconscious. Because the body “hears” everything that enters the subconscious mind, hypnosis became viewed as a method for accessing and influencing subconscious effects on the body.[72]

Clinical applications. Hypnosis involves accessing a trance state of inner absorption, concentration, and focused attention. This is established by using an induction procedure that usually includes instructions for relaxation to produce an altered state of consciousness.[73] Trance is considered a naturally occurring state that is induced by mental concentration. Attention is narrowly focused and relatively free of distractions, and the body experiences physical relaxation. This is similar to everyday experiences such as daydreaming, losing yourself in a book or movie, or getting lost in thought while driving and missing your exit. Refer to “Clinical Hypnosis” to learn more about self-hypnosis.

Hypnosis uses two strategies during the trance-like state to create changes in sensations, perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. First, mental imagery and symbolism are used to accomplish the goal of the hypnosis session. For example, a person with IBS may be asked to imagine what her or his abdominal pain looks like. If the person imagines it as being a very red, pulsing object that is hot and sharp in texture, the patient may be encouraged in hypnosis to visualize this image changing, with colors and textures shifting to those that are more representative of a healthy state (perhaps a cool blue). Other examples include preparation for surgery, such as imagining the surgery going smoothly and visualizing a successful outcome and quick recovery time. Hypnosis can also be used as an adjunct to other treatments. For example, a cancer patient may focus on imagery related to chemotherapy working more effectively. This can potentially boost white blood cell production and activity.

The second hypnotic strategy involves the use of suggestions. The therapist and the person in the trance use ideas and suggestions to support the goals of the session. The expectation is that those suggestions can have a powerful impact on the mind. They are most effective when the patient is a) relaxed, receptive, and open to the suggestions, b) able to experience visual, auditory, and/or kinesthetic representations of the suggestions, c) able to anticipate and envision that these suggestions will result in future outcomes.

Evidence. The American Society of Clinical Hypnosis (ASCH) is the largest, multi-disciplinary, national organization dedicated to research and training in clinical hypnosis. Members represent the disciplines of medicine, psychology, social work, and dentistry.

ASCH has compiled the research evidence for the use of hypnosis for certain conditions.[74] (Please refer to the ASCH website for more details). They state that there is empirical support for hypnosis being used for the following medical problems:

- Gastrointestinal disorders (ulcers, IBS, colitis, Crohn’s disease)

- Dermatologic disorders (eczema, herpes, neurodermatitis, itching, psoriasis, warts)

- Surgery/anesthesiology

- Acute and chronic pain (back pain, cancer pain, dental anesthesia, headaches, and migraines, arthritis or rheumatism)

- Burns

- Nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy and pregnancy (hyperemesis gravidarum—severe and excessive vomiting during pregnancy)

- Childbirth

- Hemophilia

- Allergies, asthma

- High blood pressure

- Raynaud’s disease

- Dentistry related conditions

ASCH also states that there is significant evidence that hypnosis may also be helpful in these psychological conditions:

- Trauma

- Anxiety and stress management

- Depression

- Bed-wetting (enuresis)

- Sports and athletic performance

- Smoking cessation

- Obesity and weight control

- Sexual dysfunctions

- Sleep disorders

- Concentration difficulties, test anxiety and learning disorders

Refer to “Clinical Hypnosis” for more information.

5. Imagery

Technique. Imagery, also known as visualization, guided or directed imagery, or even self-hypnosis, is an ancient practice and “one of the world’s oldest healing resources.”[75] Imagery is found across cultures, including in Native American and other indigenous traditions. Certainly, imagery and hypnosis are related, and imagery could be considered a subunit of hypnosis.[76]

Clinical applications. Therapeutic visualization and imagery techniques often begin by engaging in some form of relaxation. This is followed by the development of a visual image, such as a pleasant scene that enhances the sense of relaxation. Depending on the situation and clinical need, these images may be generated by the patient or suggested by the practitioner. A session might include having the patient imagine coping more effectively with the stressors in his or her life.[75]

The word “imagery” suggests that the therapy relies primarily on the visual sense, but clinical imagery typically includes multiple senses. For example, in a visualization of a relaxing place like a beach, sensory experiences might also include the warmth of the sun, the sound of the waves, the feel of the sand against bare toes, the smell of the ocean, and the feel of a pleasant breeze against the cheek. Imagery can use emotions as well, such as imagining feeling calm and peace while enjoying the beach. Using multiple senses is an advantage in guided imagery, as some individuals find it easier to imagine a scene using one sense compared to others.

Imagery is generally used in 3 ways as outlined by the Academy of Guided Imagery:[77]

- Relaxation and stress reduction, which is easy to teach, easy to learn, and almost universally helpful to patients/clients. An example would be using the imagery of the beach scene described above to foster a sense of increased peace and ease.

- Active visualization or directed imagery where the patient is encouraged to imagine desired therapeutic outcomes while in a relaxed, open state of mind. Examples include feeling more confident in a situation that is stressful, optimizing performance in some activity or sport, or visualizing a tumor shrinking.

- Receptive or insight-oriented imagery, where images are invited to enter conscious awareness where they are interactively explored to gather more information about a symptom, illness, mood, treatment, situation or possible solution. For example, if a naturally arising image for someone’s headache is a hard, black box, the individual can begin to interact with the image—perhaps opening the black box, shrinking the black box, changing the color of the box or asking questions of the black box.

Evidence. There are studies suggesting that imagery or guided imagery can be helpful in a variety of situations and conditions including stress management, preparation for surgery or procedures, pain, anxiety, depression, cancer, fatigue, childbirth, improving athletic performance, managing chronic illness, nightmares, etc.[78][79] In one systematic review focused on arthritis and other rheumatic diseases, improvement was found in pain and function across studies reviewed.[80] In systematic reviews addressing musculoskeletal pain and non-musculoskeletal pain and imagery, Posadzki and colleagues concluded that the data is encouraging but not conclusive.[81][82] One challenge in the research is that imagery is often combined with relaxation, and it is difficult to separate their effects. Studies might evaluate imagery in combination with other mind-body techniques. Over the years, research on imagery has found that it does indeed reduce stress and affect the immune system; this includes improving white blood cell counts.[83][84][85][86][87][88]

Mental rehearsal of single or complex motor acts, not accompanied by actual movement, is called kinesthetic imagery or sometimes motor imagery. Research has explored the benefits to performance when rehearsal of physical activity is performed by the self rather than merely observing someone else doing that activity in imagination. Several meta-analyses[89][90] have focused on whether this type of imagery could improve athletic performance. When a program includes both mental rehearsal of motor acts, as well as physical practice itself, performance does appear to be improved. This type of kinesthetic imagery has been used successfully to assist with physical performance across a broad range of areas, including teaching laparoscopic techniques to surgeons, playing piano, and improving soccer performance.[91][92][93] More recently, a meta-analysis found the use of motor imagery helpful for upper extremity motor rehabilitation after stroke.[94]

It is possible for nearly anyone to use this technique. Some individuals may prefer the assistance of a trained professional to help guide them in the use of imagery for their concern. Many psychotherapists, psychologists and sometimes other trained professionals can assist patients with using imagery for themselves. Those who might be especially skilled would be providers who are trained specifically in imagery or clinical hypnosis. Other providers who may incorporate imagery into their work include physical/occupational therapists, psychiatrists, nurses, and integrative medicine clinicians. Two well-known organizations providing training are the Academy for Guided Imagery and the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis. In addition, there are many imagery recordings available both in retail stores and on the Internet for a variety of health and wellness concerns.

Contraindicated imagery. It is not advised to use guided imagery with individuals who

- Are actively psychotic

- Experience hallucinations, delusions, delirium, dementia, or have difficulty separating fantasy from reality

- Feel that imagery would be in conflict with religious or spiritual beliefs

- Have a history of unprocessed trauma (which can arise suddenly during a session)

It is always important for the clinician considering using imagery to know the individual well.

Refer to “Guided Imagery” for more information

Try It for Yourself: The Power of Imagery

Note: Only do these exercises if you do not have any of the contraindications listed above.

- Imagine that you are holding half of a lemon in your hand.

- Make use of all your senses. Feel its weight in your hand. Note the bright yellow color. Smell it. Does it make any sounds?

- Now taste it. Lick the exposed surface of the fruit. Take a bite. How does it taste?

- Note your body’s response. Did you pucker up? Did your mouth water?

6. Biofeedback

Technique. Clinical biofeedback emerged as a discipline in the late 1950s, and since that time, it has expanded dramatically, as research into various biofeedback applications have demonstrated promising results. Biofeedback studies offered a concrete demonstration of the mind-body link in studies where participants were trained to alter body functions, such as brain wave patterns and heart rate. These physiological measures previously had been believed to be outside of conscious control.

The Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB) the Biofeedback Certification Institution of America (BCIA), and the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) approved the following definition of biofeedback in May 2008 [95][96][97]:

Biofeedback is a process that enables an individual to learn how to change physiological activity for the purposes of improving health and performance. Precise instruments measure physiological activity such as brainwaves, heart function, breathing, muscle activity, and skin temperature. These instruments rapidly and accurately “feed back” information to the user. The presentation of this information—often in conjunction with changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior—supports desired physiological changes. Over time, these changes can endure without continued use of an instrument.

More simply stated, biofeedback is a process in which people are taught to improve their health and performance by using signals from their own bodies. They are taught to consciously make changes in their physiology. With practice, it is possible to continue to make those physiological changes without the presence of the biofeedback equipment. In some settings, biofeedback can be used as the solitary treatment. In most clinical practice settings, however, it is used in conjunction with other treatments such as relaxation therapies. Biofeedback frequently enhances the effectiveness of other treatments by helping individuals become more aware of their own role in health and disease. Refer to “Biofeedback” for more information.

Clinical applications. The types of biofeedback that are most typically used clinically are respiration, heart rate, muscle tension (surface electromyogram), sweating (Galvanic skin response), skin temperature, and brain waves (electroencephalogram). The process of feeding back brainwaves is typically called neurofeedback.

Evidence. The use of neurofeedback to reduce intractable seizures has been investigated over the past 40 years. This is especially meaningful when one considers that one third of patients with epilepsy are not helped by medical intervention. In a meta-analysis, neurofeedback was found to benefit people with uncontrolled seizures.[98]

The management of headache using biofeedback has been found to be helpful by the United States Headache Consortium (USHC) in their evidence-based assessment of treatments (2000).[99] This group was independently formed by many diverse medical organizations including the American Academy of Neurology, American Headache Society, and the National Headache Foundation. Their “Grade A evidence” rating (i.e. treatments that had multiple well-designed randomized controlled trials revealing a consistent pattern of positive findings) was given to thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, as well as electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback. They stated that these treatments can be considered as options for the prevention of migraine.

Does Biofeedback Work? The effectiveness of biofeedback in the treatment of physical and mental health problems has undergone considerable scientific scrutiny. A rating system for efficacy for biofeedback was created and adopted by the Boards of Directors of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB) and the International Society for Neuronal Regulation (ISNR). These 5 levels are listed here from strongest to weakest efficacy:

- Level 5: Efficacious and specific

- Urinary incontinence in females

- Level 4: Efficacious

- Anxiety

- Attention Deficit Disorder

- Headache-adult

- Hypertension

- Temporomandibular disorders

- Urinary incontinence in males

Level 3: Probably efficacious

- Alcoholism/substance abuse

- Arthritis

- Chronic pain

- Epilepsy

- Fecal elimination disorders

- Headache-pediatric Migraines

- Insomnia

- Traumatic brain injury

- Vulvar vestibulitis

Level 2: Possibly efficacious

- Asthma

- Cancer and HIV, effect on immune function

- Cerebral palsy

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depressive disorders

- Diabetes mellitus

- Fibromyalgia

- Food ulcers

- Hand dystonia

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Mechanical ventilation

- Motion sickness

- Myocardial infarction

- PTSD

- Raynaud’s disease

- Repetitive strain injury

- Stroke

- Tinnitus

- Urinary incontinence in children

Level 1: Not empirically supported. This designation includes applications supported by anecdotal reports and/or case studies in non-peer reviewed venues.

- Autism

- Eating Disorders

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Spinal Cord Injury

Refer to Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB) website for further information regarding the criteria for this rating system.

In some settings, biofeedback can be used as the solitary treatment. However, in most clinical practice settings, it is used in conjunction with other treatments, including other relaxation therapies. Biofeedback can enhance the effectiveness of other treatments by helping individuals become more aware of their own role in influencing health and disease; it can be quite empowering to patients. Biofeedback is often favored by patients who enjoy working with various types of technology.

7. Meditation

Technique. The history of meditation is a very rich one, with the earliest written records of its use found 2,500 hundred years ago in the Hindu Vedantism culture of India. One of the most famous meditation teachers, Siddhartha, also known today as the Buddha, lived from 563 to 483 BC, according to tradition. Forms of meditation have arisen in many cultures and geographic locations, and while methods and practices vary they share certain underlying principles. For example, there are meditation practices within Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, among others. Yoga practices are often included under the rubric of meditation.

Although ancient, meditation is subject to a great deal of current interest. Hundreds of research studies have been conducted on both the physiological and psychological effects of meditation practice. Meditation is often classed as a mind-body technique and listed as a complementary approach. Research in meditation has increased dramatically with the coming of age of mindfulness meditation in the past few decades. Of note, there were fewer than 80 published articles on mindfulness as of 1990, and that number increased to 1,200 articles featured in PubMed by October of 2013.[100]

Defining—and therefore studying—meditation is difficult, given the broad scope of meditation types, lineages, styles, and goals. “Meditation” can be considered an “umbrella” term that includes a wide diversity of practices. Meditation comes from the Latin “meditari” meaning to engage in contemplation or reflection. Generally, in psychology, meditation refers to a practice in which the mind is trained to maintain focused attention for any number of reasons, including to enhance relaxation or develop positive psychological states.

Clinical applications. More recently, some researchers and writers have conceptualized meditation research as being two-pronged:

- Types of meditation that are more focused on concentration practices, such as Transcendental Meditation® (TM) or the relaxation response

- Those that are based in mindfulness practice, such as Zen meditation and Vipassana

TM was brought to the United States in the 1960s by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of India and was studied by Herbert Benson, a cardiologist who did pioneering research in the field of mind-body medicine.[45] Examining the physiological and psychological effects of meditation, he described the common features of concentration practices. He found that these practices led to the relaxation response, a quieting of the sympathetic nervous system. He distilled these commonalities of concentration practices to 4 components:

- A mental device on which to focus attention (eg, a mantra or the breath, etc)

- A passive attitude toward distracting thoughts (i.e. thoughts will arise but rather than repressing or following them, allowing them to pass away)

- Decreased muscle tone (i.e. settling into a comfortable position to minimize muscular effort)

- A quiet environment (limiting distractions in the place of meditation, etc).

The most common application of mindfulness in use in health care settings today is the popular 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR). Informed by Vipassana meditation, MBSR was designed to be a secular practice. Mindfulness Meditation encourages present-moment awareness; self-regulation is enhanced by having a person focus on immediate experience. In addition, it is characterized by a nonjudgmental awareness. People are encouraged to be curious, open and accepting as they focus their sensation on the breath, parts of the body, or a simple task like eating or walking. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an adaptation of the MBSR program; it is used for prevention of relapses of depression.

For further information on mindfulness training, please refer to “Mindful Awareness,” “Bringing Mindful Awareness into Clinical Work,” “Mindful Awareness Practice in Daily Living,” “Practicing Mindful Awareness with Patients: 3-Minute Pauses,” and “Going Nowhere: Keys to Present Moment Awareness.”

Evidence. Generally, meditation has been researched and clinically applied to many different types of problems, including medical and psychological conditions. A number of studies have focused on stress. In a meta-analysis on meditation and its impact on medical illness, Arias and colleagues,[101] states that

…the strongest and most beneficial effects of meditative practices occur in the domain of psychological health/functioning, as well as in the physical parameters of disease conditions that are strongly influenced by emotional distress and where the physical symptoms can perpetuate emotional distress. These findings support the hypothesis that meditative treatments have a multifaceted effect on psychologic as well as biologic function, and that secondary physical benefits may occur via alterations in psychoneuroendocrine/immune and autonomic nervous system pathways.[101]

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, meditation programs were found to be helpful for psychological stress and well-being.[102][103] Researchers found that meditation programs can result in small to moderate reductions of some of the negative dimensions of psychological stress. They can improve symptoms of anxiety and depression, which are common problems of Veterans and comorbidities with substance use and PTSD. Other reviews and meta-analyses have also found meditation helpful to anxiety,[104][105][106] and mood. MBCT has good evidence supporting its use in the prevention of relapses of major depression.[107][108] More recently, there is preliminary evidence that combat Veterans with PTSD can be helped by engagement in a group MBCT.[109] It also appears that mindfulness-based interventions may be helpful for chronic pain management.[110][112] Increasing evidence suggests that mindfulness meditation may also assist with improving insomnia, delivered through either MBSR or Mindfulness Based Treatment for Insomnia (MBTI) a meditation-based program for individuals suffering from chronic sleep disturbance.[113]

Research of mindfulness practices has been applied to many health problems such as cancer. For cancer patients, it has been found that there is an improvement in mental health and stress[114][115][116] and improved sleep and mood.[117] To date, meditation appears to be helpful for chronic disease symptoms in epilepsy, tinnitus, peripheral neuropathy and multiple sclerosis.[118] In another meta-analysis on standardized mindfulness interventions in healthcare, the authors concluded, “The evidence supports the use of MBSR and MBCT to alleviate symptoms, both mental and physical, in the adjunct treatment of cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, depression, anxiety disorders and in prevention in healthy adults and children.”[119] Recently, Katterman and colleagues in a systematic review found that mindfulness meditation was helpful in decreasing binge eating and emotional eating, in individuals with those problems.[120]

Studies have explored the biochemical correlates to meditation. A meta-analytic review suggests that meditation might have a positive impact on increased telomerase activity.[121] Chiesa and Serretti systematically reviewed the neurobiological changes as a result of mindfulness meditation.[122] They concluded that,

Electroencephalographic (EEG) studies have revealed a significant increase in alpha and theta activity during meditation. Neuroimaging studies showed that MM practice activates the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and that long-term meditation practice is associated with an enhancement of cerebral areas related to attention.[122]

The concentration meditation practice of TM was found to reduce both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in a meta-analysis.[123] A systematic review found a positive trend in favor of the benefits of mindfulness interventions across a range of psychological, physiological, and psychosocial outcomes including anxiety, depression, mental fatigue, blood pressure, perceived health, and quality of life post transient ischemic attack and stroke.[124]

Try It for Yourself: Meditation

As you may have already noted, this curriculum has many different Mindful Awareness moments, and most of them are intended to elicit the relaxation response and heighten awareness. For this exercise, try a simple challenge.

Count 10 long, slow abdominal breaths without your mind wandering away from the task.

If you notice your mind wandering gently bring your awareness back. If you have lost count, simply start again. Many people find it hard even to focus for 3 full breaths without distraction. Remember though, that the ability to catch your mind wandering and gently bring it back is a key component of meditation practice.

Don’t judge. Don’t strive. Just stop, observe, let it go, and return, as often as needed.

In summary, meditation is considered a safe and potentially efficacious complementary method for treating certain illnesses, stress-related difficulties, and non-psychotic mood and anxiety disorders. Refer to “Meditation” for additional information and more detailed reviews of research related to mindful awareness training.

Seven different Power of the Mind tools are featured above, and there are many more. Find out which ones are available where you work. If interested, choose a few techniques (breathing is a popular one) you can offer yourself. There is an increasing body of research supporting the use of these approaches.

Emotional Healing Strategies

Henry Maudsley said, “The sorrow that hath no vent in tears may make other organs weep.” Healing emotionally upsetting experiences through the use of specific therapeutic techniques improves physical and mental health, enhances immune function, and results in fewer visits to medical practitioners.[125] This section focuses on clinical techniques to use the power of the mind to heal traumatic and stressful experiences and better manage negative emotional states that may be negatively affecting health. This is of particular importance in the Veteran population, where there is a high prevalence of PTSD, depression, and other mental health issues.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Technique. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). In the last few decades, there has been a growing recognition that the mind has a powerful influence over emotional and physiological states. The development of CBT in the mid-1950s by Ellis and Beck was built on the principle that thinking patterns, not just external events and people, influence a person’s feelings and behaviors. Extensive research involving CBT has shown that maladaptive thoughts are causally linked to emotional distress and problematic behaviors. It is the most widely studied form of psychotherapy.

CBT emphasizes developing the capacity to analyze one’s thinking, identifying patterns of thought that cause suffering and distress and modifying these thoughts to create more realistic and positive ways of thinking that foster a greater sense of well-being and happiness. The field of CBT is widely used within the VA.

Techniques used in CBT include keeping a record of negative feelings, thoughts, behaviors, and beliefs so that one can learn how to accurately identify them. These are known as thought records. The goal of the thought record is to help people develop the ability to notice and observe automatic thoughts about themselves, other people, and life events. Through this observation, a person can begin to identify inaccurate, negative, or maladaptive thoughts that can lead to dysfunctional behaviors. A person can then choose to replace these negative thoughts with adaptive thoughts that are more helpful, a technique known as cognitive restructuring. These techniques are practiced by the patients themselves under the supervision of a therapist.

Many disorders are associated with common dysfunctional thought patterns. Depression is linked to negative beliefs and thoughts of hopelessness and helplessness. Anxiety disorders are linked to maladaptive cognitions related to future possibility of danger or threat. Panic disorder misinterprets the physical symptoms associated with anxiety as harmful. Social anxiety is associated with fear of embarrassment and humiliation, while generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder are characterized by excessive obsessions, worry about future undesirable events or the consequences of worry itself.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is widely available in the VA and has strong research supporting its use for many challenging-to-treat conditions.

Distorted thinking can precipitate and maintain psychopathology and can be associated with poorer coping with chronic medical issues. Many psychological disorders can be treated and prevented through examining thought patterns and restructuring to be more accurate. Cognitive distortions, patterns of exaggerated or irrational thought, are believed to perpetuate the effects of psychopathological states, especially depression and anxiety. Burns identified a list of main cognitive distortions. They include the following [126]:

- All or nothing thinking

- Overgeneralization

- Filtering

- Disqualifying the positive

- Jumping to conclusions

- Magnification and minimization

- Emotional reasoning

- Should statements

- Labeling

- Personalization

- Blame

For further descriptions of these cognitive distortions, refer to “Working with Our Thinking.”

Evidence. Hofmann et al. conducted a comprehensive meta-analytic study of CBT.[127] They identified 269 meta-analytic reviews that examined CBT for a variety of problems. They found that the efficacy of CBT for anxiety disorders was consistently strong. Large effect sizes were reported for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and at least medium effect sizes for social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medium to large CBT treatment effects were reported for somatoform disorders, including hypochondriasis and body dysmorphic disorder. They found strong support for CBT of bulimia and anger control problems. CBT was found to demonstrate superior efficacy as compared to other interventions for treating insomnia. In fact, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) was developed as a specific protocol to treat insomnia and sleep difficulties. As a stress management intervention, CBT was more effective at reducing general stress than other treatments.

The meta-analytic literature of CBT for depression and dysthymia was mixed as some research suggested strong evidence while others reported weak findings. Many studies indicate that distorted thinking can precipitate and maintain depression.[127] Restructuring distorted thinking has been found to be an effective short-term treatment and intervention for relapse prevention in depressed patients.[128] A recent review summarized more than 75 clinical trials for cognitive therapy for unipolar depression concluding that it is superior to placebo; CBT is also equivalent to other treatments, including antidepressant pharmacotherapy.[129] Cognitive therapy also seems to be superior to pharmacotherapy and similar to other psychotherapies in its effectiveness when it comes to reducing the risk of relapse of depression after discontinuation of treatment.[130] Research has shown that CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety.[131]

In short, all of these common mental health conditions are characterized by thought patterns that are unhelpful and potentially modifiable through CBT.

Hofmann et al. cited that effect sizes of CBT for treatment of addiction and substance use disorders ranged from small to medium, depending on the type of substance abuse.[127] CBT was found highly effective for treatment of cannabis and nicotine dependence, but less effective for treatment of opioid and alcohol dependence. For treatment of psychotic disorders and schizophrenia, CBT was found in this review to be effective for treatment of positive symptoms and secondary outcomes, but less effective than family intervention or psychopharmacology for chronic symptoms or relapse prevention. For treatment of chronic medical conditions, chronic fatigue and chronic pain additional research is needed.

2. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

In recent years, cognitive behavioral therapies have been deeply influenced by the rise of acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions. Steven Hayes, a main researcher in this area, has reflected that these therapies focus on changing the function of psychological events that people experience, rather than changing or modifying the events themselves.[105] One of these interventions is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

ACT uses acceptance, mindfulness techniques, commitment to values, and behavior activation techniques to produce psychological flexibility. ACT was developed in the 1980s by Hayes, Wilson and Strosahl. A cardinal feature of ACT is its differing approach towards negative thoughts. Rather than directly changing the content (eg, accuracy) of negative thoughts, ACT methods emphasize changing the function of thoughts by encouraging patients to adopt a different awareness of and relationship to their thoughts.[132] This altered relationship focuses on neutralizing (defusing) thoughts with a variety of techniques rather than repressing or changing them. Various “cognitive defusion” techniques help patients to see the “…bad thought as a thought, no more, no less…”[133] and no longer have their behavior driven by experiential avoidance or dysfunctional behavior.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ost of ACT found that it is probably efficacious for chronic pain and tinnitus, possibly efficacious for depression, psychotic symptoms, OCD, mixed anxiety, drug abuse and stress at work, and experimental for nicotine dependence, borderline personality disorder, trichotillomania, epilepsy, overweight/obesity, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and ovarian cancer.[134] ACT is not yet a well-established intervention for chronic disease/long-term conditions.[135] Ost found that ACT did not lead to significantly higher effect sizes than other cognitive or behavioral therapies in randomized studies with direct comparison of these forms of therapy.[134]

Refer to “Working with Our Thinking” for more information.

3. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing

Technique. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) was introduced by Dr. Francine Shapiro in 1989. It was presented as a new treatment for traumatic memories and PTSD, with later expansion to other anxiety disorders and phobias. EMDR is generally a multi-session intervention which uses bilateral stimulation, often in the form of eye movements, taps, or sound, with the goal of processing distressing memories, reducing symptoms, and enabling patients to develop more adaptive coping mechanisms. There is an 8-step protocol that includes having patients recall distressing images while receiving one of several types of bilateral sensory input, including side-to-side eye movements. Initially used for adults, EMDR has been found to be useful with children as well.

Evidence. One controversy about EMDR is whether the bilateral stimulation (eg, eye movements, etc) adds a specific benefit to the treatment. A recent meta-analysis of just this issue found that in both clinical and laboratory settings, eye movements (compared to no eye movements) had a medium effect size, which suggests an advantage for using eye movements over not doing so.[136] The exact psychophysiology of bilateral stimulation is still largely unknown.

Another controversy is whether EMDR is better than other treatments for decreasing distressing memories or anxiety. To date, studies show that when EMDR is compared to no treatment, patients are better off with EMDR treatment than without. When compared to no treatment or to nonspecific therapies, EMDR is again shown to have positive effects. Results have been consistent across studies that use different measures, and focus on a variety of complaints.[137][138] Research suggests that EMDR is of similar efficacy to other exposure therapies and more effective than medication alone or treatment as usual.[139][140][141][142] [143]A meta-analysis compared CBT to EMDR and EMDR treatment appeared slightly superior to CBT.[144]

There is also some suggestion that EMDR might be effective in reducing pain including postoperative pain, and chronic nonspecific back pain when accompanied by trauma.[138][145]

For additional information on EMDR and other treatments for PTSD, refer to “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)”.

4. Cognitive Processing Therapy and Prolonged Exposure Therapy

Techniques. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)[146] and Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE)[147] are two of the most widely studied psychological treatments for PTSD. Both CPT and PE have been found to produce clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms in multiple randomized controlled trials.[148][149] Although these treatments share many common factors, the focus of CPT is on changing maladaptive thoughts, while the main mechanism of PE is exposure exercises.

More specifically, CPT typically involves 12 sessions that directly work on modifying maladaptive thoughts that have developed following the traumatic incident, such as those about safety, trust, control, self-esteem, other people, and relationships. Working towards developing a more balanced and healthy appraisal of the traumatic event, oneself, and the world helps to promote recovery from PTSD.

PE, on the other hand, involves 8-15 sessions during which a patient talks through the traumatic memory by doing repeated imagined exposure exercises. In addition, the patient does in vivo exposure exercises, to activate the fear associated with the trauma and provide a corrective experience. Over time, this exposure leads to the habituation/extinction of conditioned fear responses.

Evidence. Evidence was found for concurrent change in PTSD and depressive symptoms during CPT.[150] PE has been found to reduce anger, guilt, negative health perceptions and depression.[151]