Humans have survived over the generations because we were closely attuned to the world around us. It is important to do our “inner work,” but we must balance that with being attuned to our external world, our surroundings, as well. Surroundings, though not often featured in clinical discussions, is an important aspect of self-care in the Circle of Health. Topics related to surroundings, which can inform Personal Health Plans (PHPs) include where we live, where we work, and how the external world affects our emotions. Other topics include avoiding toxins, spending time in nature, and seeking health care in facilities that are truly healing spaces. This overview builds on Chapter 6 of the Passport to Whole Health.

Key Points

- Research in the field of epigenetics indicates that our surroundings have the power to affect us at the level of our genes, through a variety of biochemical mechanisms.

- Optimal healing environments—the surroundings that are most conducive to health and well-being—require a balance between internal, interpersonal, behavioral, and external forces that influence our health.

- The Veteran Handout “Assessing Your Surroundings” can guide Veterans and clinicians as they incorporate Surroundings into PHPs.

- When you consider living spaces, keep topics like homelessness, clutter, neighborhood crime, pests, and the presence of weapons in mind, in addition to other specific attributes of someone’s home.

- Elements of a healthy work environment include good ergonomics, taking breaks, and an absence of workaholism as well as good relationships with colleagues and fine-tuning the attributes of the work space itself.

- People are exposed to thousands of potential toxins every day. Through healthy lifestyle choices and avoiding exposures as much as they are able, they can decrease their overall toxic burden.

- Healing spaces can have a favorable impact on patient outcomes. Pay attention to lighting, noise, art, temperature, other factors that research indicates can support healing.

Meet the Veteran

A man is not rightly conditioned until he is a happy, healthy, and prosperous being; and happiness, health, and prosperity are the result of a harmonious adjustment of the inner with the outer of the man with his surroundings. —James Allen

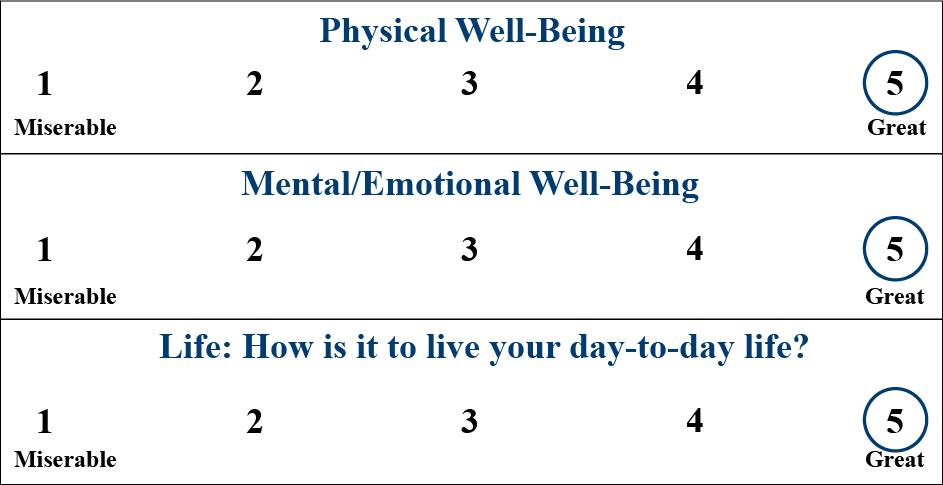

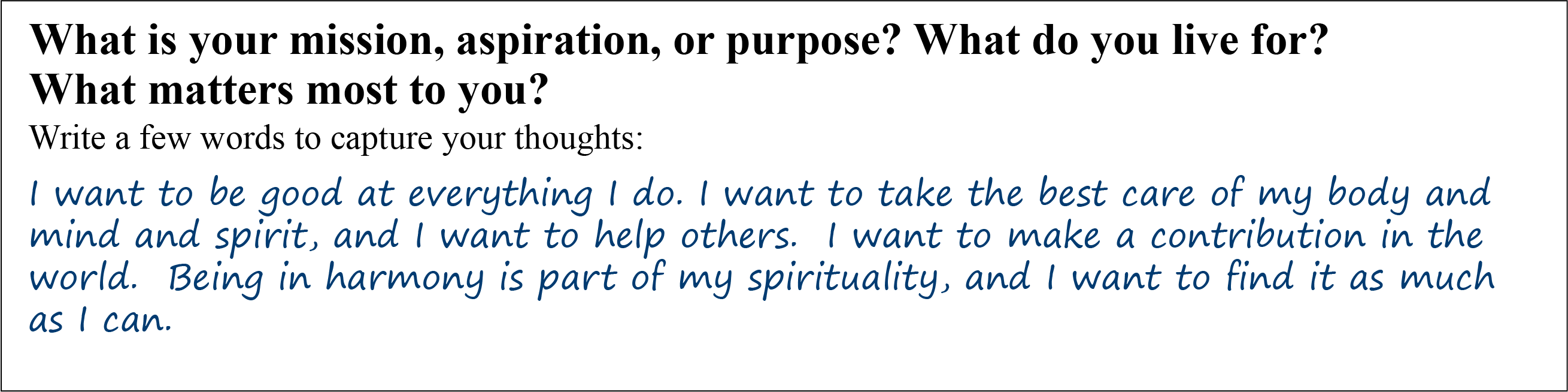

You are meeting Andre, a 30 year-old Marine Corps Veteran who is new to the VA system. He arrives at his visit with a completed Brief Personal Health Inventory (PHI). As you review Andre’s PHI, you are struck by the following:

He rates himself 5/5 on all the vitality signs.

He has a unique answer for the question designed to capture Mission, Aspirations, and Purpose (MAP).

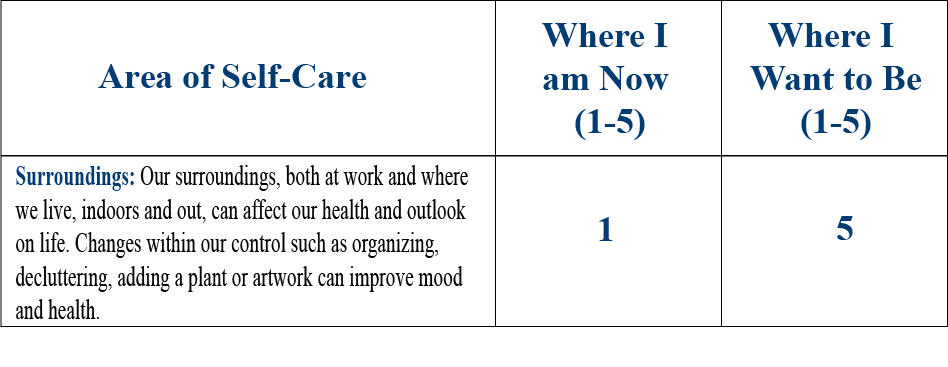

Andre gives himself a 4/5 or a 5/5 on every self-care item but one.

The final question on Andre’s PHI verifies that “Surroundings” is his highest priority for his PHP.

Surroundings is not necessarily a topic that comes up in much detail during a clinician’s training. How do you create a PHP that focus on this aspect of self-care?

Introduction

Surroundings powerful influence on health has been recognized for as long as humans have had systems of healing. In most indigenous healing systems around the world, healers (shamans, medicine men and women, etc.) have explained and treated disease, at least in part, using elements from the natural world. For millennia, Chinese Medicine has emphasized the importance of environmental contributors to ill health. This includes the “Six Pernicious Influences”—heat, cold, wind, dampness, dryness, and summer heat—which are thought to cause imbalances in body, mind, and spirit.

Sometime around 400 BCE, Hippocrates wrote On Airs, Waters, and Places, which highlighted the influence of surroundings on health. He noted,

Whoever wishes to investigate medicine properly, should proceed thus: in the first place to consider the seasons of the year, and what effects each of them produces, for they are not at all alike, but differ much from themselves in regard to their changes. Then the winds, the hot and the cold, especially such as are common to all countries, and then such as are peculiar to each locality. We must also consider the qualities of the waters, for as they differ from one another in taste and weight, so also do they differ much in their qualities.

The Biophilia Hypothesis asserts we are hard-wired to be closely attuned to the world around us. In part, because it was vital to our ancestors’ survival, but we are still drawn to locations that allow us to thrive.[1] Our health is contingent not only on what takes place internally, but how we are influenced by our external world through the sensory information, the media, our interactions with others, weather and climate changes, what we eat and drink, etc.

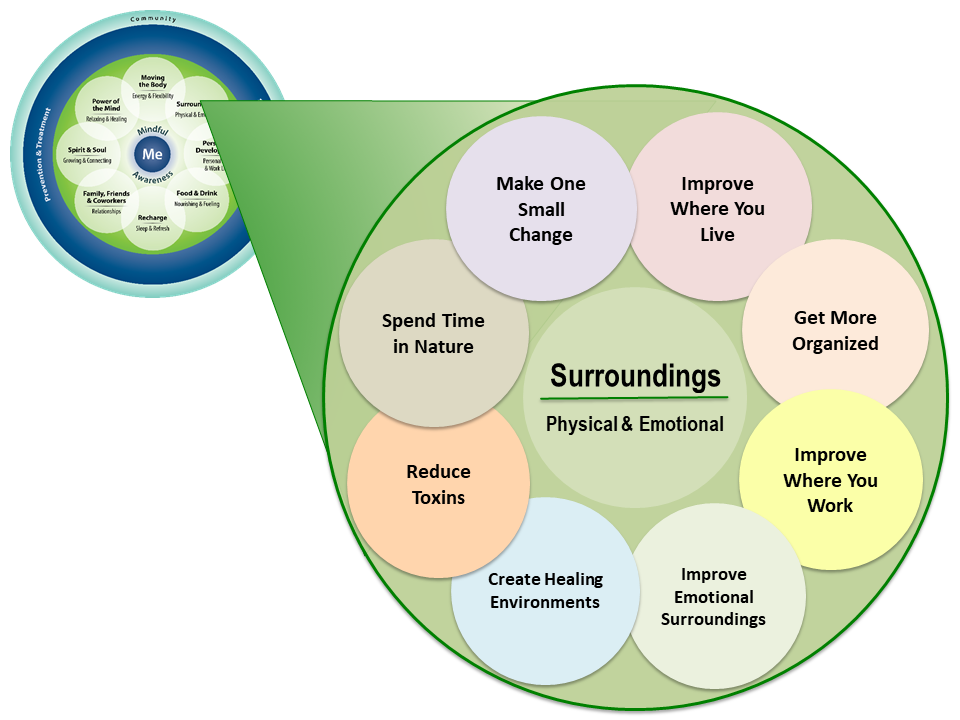

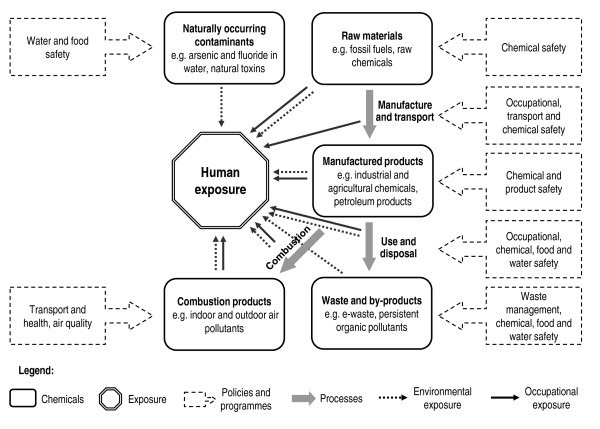

In the Whole Health Skill-Building Courses for Veterans, Figure 1 is used to give Veterans a framework for thinking about Surroundings and incorporating goals for that aspect of self-care into their PHPs.

After discussing some important general topics related to surroundings like epigenetics and optimal healing environments, this overview will explore the topics shown in Figure 1 in greater detail. For a general introduction to Surroundings, refer to Chapter 6 of the Passport to Whole Health.

Epigenetics

Environment is thought to contribute to 80% of our risk of disease[2]. We know that in pairs of identical twins, one twin may express a trait or have a particular disorder, while the other does not. Why the difference? Each twin’s environment—his or her surroundings—plays a significant role. One twin may have had more sun exposure. One may have smoked, while the other one did not. One may have exercised more, or have had less exposure to a particular toxin in the environment, such as cigarette smoke.

Epigenetics was first defined by the biologist Conrad Waddington in the 1950s as the study of how information, in addition to our DNA sequences, influences genetic expression. Over time, it has become increasingly clear just how susceptible our genes are to changes in our surroundings. Epigenetic changes are tied to the development of cancer, occurring long before cancer actually develops. They also precede autoimmune diseases and type 2 diabetes.

Epigenetic information takes three different forms. These include:

- DNA methylation. Methyl groups are attached to the nucleotide cytosine in the DNA. Methyl groups can be copied when DNA is and they can also be erased. More variability in DNA methylation is tied to more aggressive leukemias and lymphomas,[3][4] as well as risk of breast cancer.[5] There are also links to autoimmune diseases[6] and obesity.[7]

- Histone modification. Histones are proteins found in cell nuclei that serve as “spools” for DNA to wind around to form nucleosomes. Without them, it would not be possible for all of a cell’s DNA to fit into the cell nucleus. Histones can be modified in over 200 different ways, to alter the genetic expression of the DNA associated with them.

- Changes of higher order chromosome structure. An example of this type of epigenetic information is the way nucleosomes cluster together near a cell’s nuclear membrane. This type of epigenetic information gives a cell instructions based what type of a cell it is. In liver cells, certain genes are unwrapped from histones and activated, but they would not be in a skin cell or cell from other types of tissues.

Particularly fascinating has been epigenetic research indicating that environmental exposures can have intergenerational effects.[2] One’s environment not only influences their gene expression, but also the gene expression of their descendants. For example, under normal circumstances, agouti mice are genetically destined to have yellow fur and the mouse equivalent of obesity. However, this phenotype—how their genes are expressed—can be changed by what their mothers are exposed to while pregnant. A mouse can develop to be dark-furred and non-obese, despite its agouti genetic profile, if its mother is fed foods containing methyl donors (e.g. onions, garlic, beets) prior to giving birth.[8] In humans, mothers who smoke cause epigenetic changes in their babies.[9] Methylation changes in sperm cells have been found to carry down through generations in autistic fathers and their autistic sons.[10][][11] Parents who experience starvation are more likely to have children with type 2 diabetes[12]. Prenatal stress a mother experiences is linked to the development of a variety psychological problems in her child[13].

Epigenetics is currently one of the hottest areas of medical research out there. It may soon be possible to personalize the clinical management of a number of health issues; such as obesity, where eating patterns can be shaped based on a person’s personal epigenetic profile. The epigenetics of other disorders, such as PTSD,[14] mood disorders, [15] asthma,[16] and various cancers[17], is also a promising area of research[18]

Never underestimate the power of surroundings on health. Epigenetics research demonstrates numerous ways in which our environment changes us at the genetic level.

Optimal Healing Environments

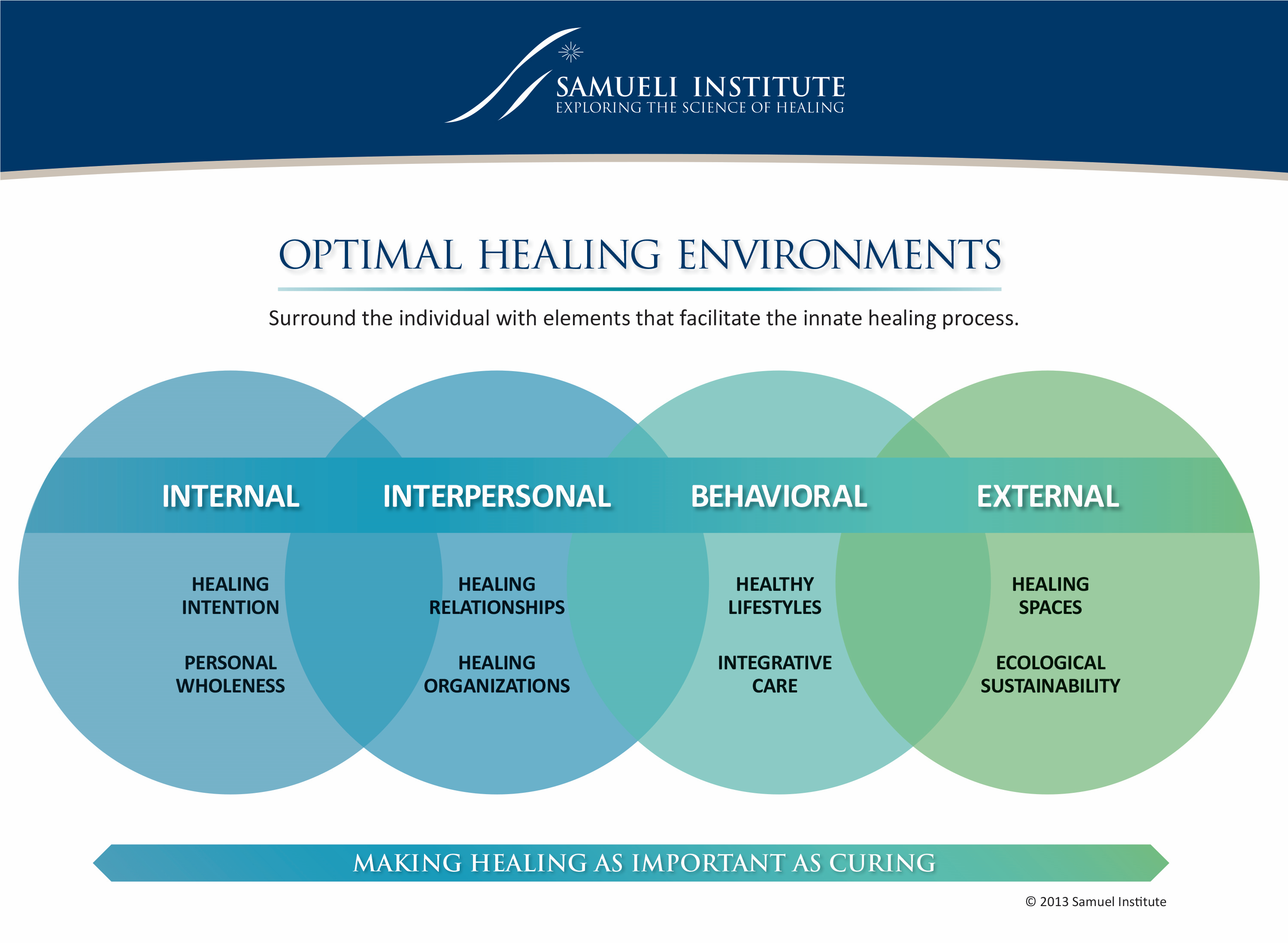

We have looked at the influence of Surroundings at the molecular level in terms of epigenetics. What about at the “macro” level? In 2004, the Samueli Institute put forth a series of monographs outlining what an “optimal healing environment” (OHE) is and how any home, workplace, institution, or larger group can move closer toward being one. [19]

There are eight key elements of an OHE, as follows:[20]

- Healing intention. Conscious development of intention, awareness, and expectation, including the belief that healing can occur.

- Personal wholeness. Self-care practices on the part of the clinician and the patient.

- Healing relationships. A therapeutic alliance predicated on compassion, love, and the interconnectedness of all is of key importance.

- Healing organizations. Institutions, communities, and social groups buy into creating/being OHEs.

- Healthy lifestyles. Health promotion is fundamental, with self-healing and social support as important elements.

- Integrative care. The best conventional and complementary approaches are used.

- Healing spaces. Physical and natural surroundings—light, air, color, temperature, sound—also contribute to health.

- Ecological sustainability. The most “macro” level of all. A healing environment also supports the health of the larger environment—ecosystems, the climate, and the well-being of our planet as a whole.

The Samueli Institute created a graphic that illustrates how these eight elements fit together (Figure 2). Note that many of these, including relationships, healthy lifestyles, and integrative care –in addition to surroundings– are also components of the Circle of Health. Whole Health. How can you make your home and your workplace OHE’s? How can you help your patients do the same? How do you support the creation of OHE’s at the institutional level?

Mindful Awareness Moment

Different Perspectives on Surroundings

Spend a few minutes thinking about your practice environment.

- Start by visualizing where you practice from a patient’s eye view.

- What is it like to check in, to interact with a receptionist, or to be admitted through the emergency department?

- Imagine the perspective of a patient sitting in your waiting area, about to have a visit with you, their clinician. What would this patient notice?

- How is the lighting?

- What colors are the walls and furnishings?

- What about the noise level? Is there music playing?

- How is the temperature?

- Are the chairs comfortable?

- Are there any antiseptic smells (or other smells)?

- Are there interesting and up-to-date magazines to read?

- How tasteful is the art on the walls?

- Are there any natural elements (plants, windows, fountains)?

- Is there a TV in the waiting room? What shows are likely to be on?

- Ask the same questions about the spaces where patients meet with you, be it a hospital room, an exam room, an office, etc. What sort of impression does your practice space make? What is good about the space? Where is there room for improvement?

- Now, consider the healing environment where your work from your perspective.

- How do you feel about where you practice, in terms of the eight elements of an OHE listed above? Take a moment to consider how each one fits in for your Surroundings.

- Is it possible to set healing intentions and focus on personal wholeness, for yourself and your patients?

- How easy is it to foster healing relationships in this environment?

- Is your organization—your department or section, your hospital, your clinic—supporting the creation of OHEs? Why or why not?

- Is your workspace comfortable, with good ergonomic support, sufficient lighting, and clean air?

- Are you able to practice in an environmentally friendly way?

- Is the overall work situation good for you? Do you feel supported by your colleagues? Do you feel respected? Do you have any “toxic” colleagues?

- Do you look forward to being in your work environment each day, or do you dread it?

- What is one thing you could do right now to make your surroundings more healing, both for you and for patients?

Assessing Surroundings

For someone like Andre, it will help to go into more detail about Surroundings as part of the Whole Health Assessment. One way to do this is to use the questionnaire, “Assessing Your Surroundings.” This questionnaire covers five areas: Home, Work, Toxins, Senses, and Emotions. It can be a springboard into conversations about how to incorporate Surroundings into the PHP.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Assessing Your Own Surroundings

- How is your home environment? What one thing could you change, right now?

- How about your work environment?

- What sort of emotional surroundings do you experience each day?

- How much do your surroundings –physical and emotional– affect your well-being?

- How important are your surroundings to you, compared to the other seven areas of self-care (the other green circles within the Circle of Health)?

Consider completing the “Taking Stock: Assessing Your Surroundings” tool yourself.

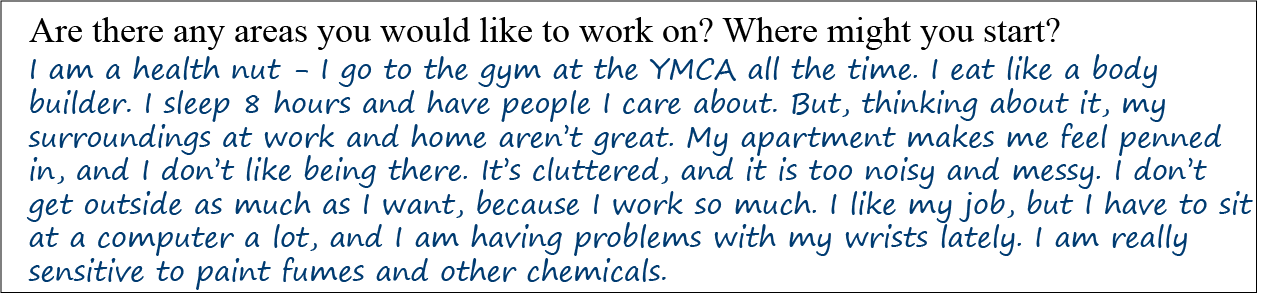

When Andre completes the “Taking Stock” form, several possible areas arise that could receive more attention in his PHP.

- Home. Andre lives alone. He rents apartment that he does not like. The cost of living is high in the city where he lives, so he has to he keeps room temperatures cold in the winter. He lives in a neighborhood that has a lot of crime. His home is cluttered, but he keeps it clean. He is not a hoarder. Sometimes he sees roaches. He has a smoke detector. No air conditioning, but fans work to cool down his apartment. He drinks filtered water.

- Work. He likes his job in telephone sales, but he is pretty competitive, and he thinks that makes his fellow salespeople not like him. He works in a cubicle that is very noisy. He has not taken the time to decorate it. He has had carpal tunnel syptoms lately from using his computer. He takes a total of 10 minutes of breaks a day, he works through his lunch. His office environment has some natural light, and is never too cold or hot.

- Toxins. Andree does not know of any military exposures from his time in Iraq. His neighbor smokes, and he really hates it. No environmental allergies, but he tries to avoid gluten. He thinks there is some asbestos in his building, but they have supposedly taken care of it.

- Senses. His living space is neither comfortable nor peaceful. His sleep is poor because of noise and a lot of light coming through his bedroom curtains. His apartment has radiators that do not work well, and he hates to pay for electricity for portable heaters. He wishes he had more light. No plants, okay furniture. He does not have any art or photographs on the walls.

- Emotions. Andre reports being happy once a week, usually after a he makes good sale at work, or if he has a date that goes well. No experiences of violence at home or at work. He does not have any close friends or family who are local. He says he spends too much time online and he gets caught up following the news, even though it stresses him out. He works 60-70 hours a week, because he works on a commission. No vacations in the past year. Too tired at the end of the day for hobbies.

The next five sections explore various aspects of Surroundings in greater depth. Note that all the circles highlighted in Figure 1 are covered at some point.

1. Home: Improving Living Conditions

He is happiest, be he kin or peasant, who finds peace in his home. –Goethe

When you are helping a Veteran create a PHP focused on Surroundings, it is helpful to start with a discussion of their living situation. Do they have a home? Who lives with them? What is it like to live there? How clean and organized is it? How comfortable is it? According to the National Center for Healthy Housing, a healthy home should be all of the following[21]:

- Dry

- Clean (refer to the discussion on clutter, collecting, hoarding, and squalor later in this section)

- Pest-free

- Safe

- Contaminant-free (refer to “Section 3. Exposures and Toxins” below)

- Ventilated

- Maintained

Back to basics: Homelessness

Before people can focus on their home environment, they need to have a home in the first place. Always keep homelessness in mind as you are exploring Surroundings with a Veteran. Here are some key facts on homelessness:

- Lifetime prevalence of homelessness in the United States has been estimated to be between 5% and 14%.[22]

- Veterans comprise 11% of the adult homeless population. As of 2017, an estimated 40,000 Veterans are homeless on a given night, 15,000 of those are unsheltered or living on the street[23]. Male Veterans are 30% more likely to be homeless than men who are not Veterans.

- Female Veterans are twice as likely to be homeless[24] than other women. 8% of VA homeless services users (2011-2012 data) are women, and 21% of them have dependent children.[25]

- 73% of homeless people have unmet health needs.[26] An estimated 40% of homeless people are dependent on alcohol, 25% are dependent on drugs, and mental illnesses are common as well, with a prevalence of 11% for depression, 23% for personality disorder, and 13% for major psychotic illness.

- Homeless Veterans have four times the odds of seeking care at emergency departments (EDs) than non-homeless Veterans. Homeless ED users were more likely to have a diagnosis of drug use disorder (odds ratio [OR] = 4.12), alcohol use disorder (OR = 3.67), or schizophrenia (OR = 3.44) in the past year.[27]

- A review of 31 studies found that homeless Veterans are more likely to be older, better educated, male, married, and insured when compared with other homeless adults in the U.S[28].

- Fortunately, the federal strategic plan to decrease homelessness in the United States has made a difference. Through the efforts of the VA, homelessness among Veterans declined by 50% between 2010 and 2017[23].

Resources for Homeless Veterans

- Information on homelessness programs and initiatives through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

- VA drop-in centers, supported housing, and work therapy options

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs success stories about homeless Veterans. Inspiring accounts of Veterans who have faced homelessness and prevailed

- The National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. Has a helpline available to support Veterans needing homelessness resources and support. Contact at 1-800-VET-HELP or 1-800-838-4357.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Homeless Veterans Aid Line. Contact at 1-877-4AI-DVET or 1-877-424-3838.

Clutter, collecting, hoarding, and squalor

In his PHI, Andre expressed concern about the level of clutter in his home. Some people simply need guidance or encouragement related to tidying up, but for others, the situation may be more complex. A home visit might help assess the severity of the problem, if appropriate.

Hoarding

An estimated 5% of people fit the criteria for being hoarders.[29] Hoarding is included in the fifth Diagnostic and Statistics Manual (DSM-5) as a discrete diagnosis. Hoarders are not just collectors; they are not just dealing with clutter or challenges with being organized.[30] Their living spaces are cramped, unsanitary, and potentially dangerous. The key characteristic of hoarding behavior is that it interferes with a person’s quality of life and normal functioning. In roughly half of hoarders’ homes, items such as the sink, tub, stove, or shower are not used because they are full of accumulated objects.[31]

Hoarding behavior seems to begin for many in the teen years after a traumatic or stressful event, and it typically worsens in middle age.[31] It has been linked to genetics, neurocognitive functioning, avoidance tendencies, and personality traits[32]. Hoarding runs in families, and 75% percent of the time, it is associated with other mental health issues, such as depression, alcohol abuse, anxiety, or dementia. Hoarding behavior is viewed by many as being closely related to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and people who have OCD and are hoarders have worse outcomes than people with OCD who do not hoard. Hoarders seem to experience negative emotions more intensely and to have lower tolerance for them[33].

If a Veteran mentions dealing with a lot of clutter, it is worth exploring whether or not he or she meets criteria for hoarding behavior. Unfortunately, diagnosing it is easier than effectively treating it. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are now thought to be more helpful than previously assumed,[34] and cognitive behavioral therapy is helps too.[34] A small study found venlafaxine to be helpful[35]. Forcible cleaning and organizing by a family member or other concerned party does NOT improve the situation, primarily because most people who hoard do not view their behavior as problematic. Furthermore, they tend to refill a newly cleaned space with new hoarded items. One tragic outcome of hoarding behavior is that hoarders experience a high level of rejection by family members; it is on par with the rejection experienced by schizophrenics.[31] For more on hoarding, check out the information available through the National OCD Foundation.

Squalor

In contrast to hoarding, where accumulated objects may lead to unsanitary conditions, squalor specifically involves the accumulation of refuse (garbage) in the home.[36] In a review of over 1,100 cases of people living in squalor, half of them were elderly, and they commonly struggled with dementia, alcoholism, or schizophrenia as well.[37] Questions from the “Environmental Cleanliness and Clutter Scale,”[38] (ECCS) can help, assess for squalor. Scoring 12 or higher on the ECCS scale suggests a person lives in squalor.

Key questions the ECCS focuses on include:

- How easy is it to move around the dwelling?

- Accumulation of garbage. How much refuse is there in garbage cans, the kitchen sink, etc.?

- Collection of “items of little obvious value.” Do they have huge numbers of plastic backs, old newspapers, pieces of thread, or other such items?

- Cleanliness of floors, carpets, furniture, bathrooms, and the kitchen. Are things hygienic?

- Presence of odors. Is there a foul smell?

- Presence of vermin. Did you see anything scurrying around when you visited their home?

The website, Squalor Survivors, has suggestions for how to help people living in squalor.

Living Conditions: Other Considerations

Pests

Whether someone is living in squalor or not, ask about pest control, if appropriate. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a number of resources on dealing with different pests. In the past several years, bed bugs, in particular, have made a comeback in many American homes.[39] The CDC website has a patient information page on bed bugs. Good resources for health care professionals include the educational materials at the University of Kentucky Entomology website.

Accident prevention

In addition to reminding people about having smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, be sure to assess for fall risk, if possible. A good VA resource for this is the Falls Toolkit.

Weapons

As you think about surroundings, be sure to ask Veterans if they have any weapons at home. Death certificate reviews from nine states indicate that male Veterans are 6% more likely to commit suicide with firearms than non-Veterans, and the likelihood is 18% higher in female Veterans.[40] ALWAYS ask about suicide risk. When appropriate, pass along the number for the Veterans Crisis Line: 1-800-273-8255.

2. Work Conditions

Surroundings at work, both physical and emotional, also influence health. Employed Americans with children have workdays that are an average of 8.8 hours long.[41] It is important, knowing that a significant proportion of many people’s lives are spent at work, to ensure that work surroundings are as healthy as possible. Having a job at all is good for one’s health, and factors like work safety, ergonomics, and relationships with coworkers matter as much as the physical attributes of a person’s workspace. If a person has a job that they find stimulating, and they have a lot of autonomy at work too, 34% decrease in their odds of dying[42]. Of course, dealing with the demands of work can lead to problems. For more information, refer to “Workaholism.”

Back to basics: Unemployment[41]

Having an income, much like having shelter, is a fundamental need. Data for 20 million people indicates that not having a job markedly increases mortality; the hazard ratio is 1.63.[43] Unemployment also contributes significantly to chronic illness, including many mental health problems.[44] The relative risk of suicide in those who have become unemployed in the past five years, as compared to those who are employed, is 2.50.[45]

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics,[41] the unemployment rate for Veterans who have served since 2001 is 4.5%, and the rate for all Veterans was 3.7% in 2017. Unemployment for women Veterans is slightly higher at 4.1%. Of the 370,000 unemployed U.S. Veterans in 2017, 37% were over the age of 55. Veteran unemployment rates have dropped by over 1/3 since 2013.

24% of Veterans who have served since September 2001 reported having service-connected disability as of August 2017, but their employment rates were equivalent to those of Veterans with no disability.[41] For more information about opportunities for Veterans refer to Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment website.

Ergonomics and repetitive use injuries

Keep ergonomics in mind as you think about surroundings. Ergonomics is, as the CDC puts it, “the scientific study of people at work.”[46] Its goal is to reduce problems related to repetitive use of muscles, muscle overuse, and poor posture. The goal of ergonomics is to enhance health at work by improving the quality of the workspace environment and tailoring tasks and tools to an employee’s capabilities and limitations. Ergonomics changes can support individual employee’s health and well-being, and they can also lead to a more sustainable workforce[47].

Mindful Awareness Moment

Notice your body position right now, as you are reading this material. How are you doing from an ergonomics standpoint?

- Are there any parts of your body that feel fatigued?

- Your neck?

- Your lower back?

- How do your hands feel turning pages or using a mouse or a keyboard?

- Are your eyes fatigued?

- How are the ergonomics of other places where you spend a large proportion of your time?

- For workspaces, either at home or at work?

- What about for where you sleep?

Think of one positive change you can make, and set a goal.

Study findings regarding the efficacy of ergonomic interventions are mixed, but they find moderate benefit for some conditions, such as work-related neck problems. Chair-based interventions seem to help reduce musculoskeletal symptoms,[48]. There is less data supporting ergonomic interventions for the upper limbs, [49] and it is not clear that ergonomic positioning or equipment help for carpal tunnel syndrome.[50] A 2015 review of 28 studies related to ergonomics and health care concluded that ergonomic interventions, in general, improved outcomes for health care workers[51] overall.

Various work-related interventions are safe to try, and they are worth discussing with Veterans who have work-related problems. For people like Andre who work at a computer we know that ergonomics is worth offering[52]. For more information, check out the “Improving Work Surroundings through Ergonomics” tool. It offers specific suggestions for common work-related problems.

3. Exposures & Toxins

We are exposed to thousands of toxins daily, including air pollutants, pharmaceuticals in our drinking water, heavy metals, and pesticides. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that at least 12.6 million people die each year because of preventable environmental causes, almost a quarter of all yearly deaths[53] worldwide.

A 2011 systematic review found that in 2004, 4.9 million deaths (8.4% of the total number worldwide) and 86 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) were attributable to specific environmental exposures.[53] The biggest culprits were smoke from solid fuel use, second-hand smoke, occupational exposures, chemicals involved in acute poisonings, and air pollution. Indoor air pollution, specifically, has been linked to 3.5 million deaths each year[54]. The authors note, however, that many chemicals known to cause harm could not be included in their review due to lack of data; we simply do not study all the potentially harmful compounds we are already using.

When thinking about surroundings and health, it can be less overwhelming if one focuses on reducing total chemical burden; that is, focus on specific ways to reduce just one or a few exposures at a time. Exposures a person could minimize can include anything from cigarette smoke or wood smoke to chemicals used in farming and car exhaust. One can eat foods that are less likely to contain pesticide residues, avoid bisphenol A in beverage containers, or use more “green” household cleaning products, for example. For more information specifically about toxins in food, refer to the “Food Safety”. Chapter 6 of the Passport to Whole Health includes a clinical tool on “Detoxification” that discusses what we know about popular ways to “detox” the body.

The diagram in Figure 2 conceptualizes the various types of exposures we might encounter in our day-to-day lives.[53] Again, working to reduce any one of these may be beneficial.

The number of potential environmental toxins is vast. Fortunately, there are a number of resources that can be helpful. If you or a patient would like a place to start, consider the National Library of Medicine Toxtown website. This site has user-friendly images that not only show the user potential sources of toxin exposure but also link to reliable government sources of additional information.

The National Library of Medicine’s Medline website includes a well-done introduction to environmental health and links to key resources. Check out the “Related Health Topics” list on the right side of the screen. Topics include air pollution, drinking water, mold, and noise, and water pollution.

To obtain specific information and find reliable resources about specific toxins, Toxnet (offered through the United States National Library of Medicine website) is an excellent database to use. Users can enter any chemical or other substance of concern and receive information and resources about it. Among the databases searched is the HAZ-MAP database, which describes, in detail, how to handle occupational exposures to various compounds. Toxtown, mentioned earlier, also contains a searchable list of toxins at Chemicals and Contaminants.

Remember, as you discuss exposures with Veterans, ensure that they have been asked about the following:

Encounters during time in service (and elsewhere) to radiation:

- Exposure to Agent Orange or other chemical weapons

- The presence of shrapnel in their bodies

- Encounters during time in service (and elsewhere) to radiation.

Environmental Exposure Resources

Water quality

- United States Geological Survey: A Primer on Water Quality

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Drinking Water Frequently Asked Questions

Moisture and mold

- National Library of Medicine mold resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention information on mold

- World Health Organization Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality Information on “Dampness and Mould.”

Electromagnetic fields (EMFs)

- Nice summary of the research related to known health effects. This is a controversial topic.

Idiopathic Environmental Intolerances (IEI’s)

Our patient, Andre, notes that paint fumes and other chemical odors elicit various symptoms for him. He is likely one of 12-30% of people who have idiopathic environmental intolerance (IEI) to airborne chemicals.[55]

IEIs have been given many names, ranging from sick building syndrome to multiple chemical sensitivity. Gulf War syndrome shares similar characteristics. Some key points to know about working with these challenging conditions include the following:[56][57]

- Many organizations do not recognize IEI-related disorders as “official” diagnoses.

- Theories about the etiology of these problems abound. Some focus on biochemical pathways, while others emphasize the relationship between IEIs and mental health-related issues.

- IEIs are chronic, with reproducible symptoms that are often elicited with low levels of multiple, unrelated chemicals. Symptoms are reproducible and can involve any number of organ systems.

- These disorders have any number of triggers; common examples include off-gassing from appliances, ink, exhaust fumes, and chlorinated water.

- Many different symptoms are associated with IEIs, which makes treatment especially complex.

- The best ways to treat these disorders is avoidance, which can be quite challenging if a person is experiencing symptoms related to items in or near their homes. Biomolecular approaches (medications, supplements) do not seem to be particularly effective for IEIs, according to large-scale surveys of people with these conditions. Mindful awareness and mind-body practices, are generally viewed by patients as the most helpful approaches they have tried.

- These problems can resolve over time, but not for everyone.

- For additional information that can be used for both patients and clinicians, refer to “An Integrative Approach to Environmental Intolerances: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity and Related Illness.”

4. Sensory Input and Health

When you think of a healing environment, what comes to mind? A spa? A Japanese garden? Perhaps a corner of your house? Few of us would immediately think of a clinic or hospital. But that view is beginning to change as health care organizations are becoming aware of the growing body of evidence that shows the benefits of a healing environment, and are incorporating ideas generated by such studies into new facilities. [58]

Healthy food for the senses: simple approaches

We know that our sensory environments have a significant impact on health[59]. Light levels affect mood and sleep quality.[60] Loud noises can influence blood pressure and heart rate for hours after a person hears them. Music can have a variety of effects, including calming, depending on the type of music and individual preferences[61]. Choosing the right color can change the feel of a space; cool tones slow the autonomic nervous system, while warm tones activate it.[62] Art—particularly art that features the natural world—improves patient outcomes.[63] A 2014 Cochrane review reported that additional studies are needed, but there is no harm in changing sensory surroundings to support health[64]. A 2014 systematic review concluded that the “built environment” of a hospital plays an important role in outcomes, particularly when it comes to audio and visual aspects[65] of a space.

In discussing sensory input with Veterans, take a moment to ask them to describe their living and work spaces in more detail. Explore topics covered in section four of the “Assessing Your Surroundings” questionnaire. These include:

- Light (light levels during the day and during the night)

- Noise (traffic, sirens, neighbors)

- Color

- Temperature (sufficient heating and air conditioning)

- Presence of nature (plants, aquariums, views outside)

- Smells

People often have a number of great ideas about improving their sensory surroundings, if they are simply given a bit of encouragement. Examples include the following:

- Buying light-opaque curtains or a sleep mask

- Wearing earplugs to bed

- Painting a room or adding more art to the walls

- Buying an electric heater or fan

- Buying a plant or fresh flowers

- Walking in a local park

- Opening windows

- Having smokers cut back and/or smoke outdoors

- Cleaning with less noxious household products

- Changing humidity levels to decrease mold growth

Sensory inputs and beyond in health care settings

Environmental design draws from evidence-based findings regarding what aspects of a health care environment can enhance health, above and beyond what is “done to” patients in terms of tests and procedures. It factors in the following areas, among others, as fundamental aspects of OHEs[66]:

- Patient choice and control

- Enhancing human connection

- Reducing negative sensory inputs

- Ensuring patients can find their way around a given site

- The presence of art and subject matter that is most healing

- The role of color in healing environments

- The importance of light and sound levels for healing

- Music and healing

- Drawing nature into health care settings

For more detailed information about each of these, along with a synopsis of research findings and specific guidelines for how you, as a clinician, can use environmental design in your own practice refer to, “Healing Spaces and Environmental Design” in Chapter 6 of the Passport to Whole Health. There is also “Informing Healing Spaces through Environmental Design: Thirteen Tips,” a tool that goes into more detail regarding research findings.

The power of nature[67]

Whenever you create a PHP with a Veteran, consider whether or not spending more time in nature—time in green spaces—would be helpful. There is good support in the medical literature for spending time in parks, gardens, and other areas of natural beauty. Here are some examples of some relevant studies:

- An analysis of data from the US Nurses’ Health Study found that those with the highest quintile of “cumulative average greenness” near their home had a 12% lower rate of all-cause nonaccidental mortality than nurses in the lowest quintile[68]. A review of 12 studies that involved millions of people around the world found a correlation with “higher residential greenness” and mortality from cardiovascular disease, but it noted more data were needed to determine if there was a reduction in all-cause mortality[69].

- Prevalence of 15 out of 24 different “diseases clusters” was lower for people living within a 1 kilometer of green spaces, in a study that included data for over 345,000 people in the Netherlands[70]. Depression and anxiety were affected more favorably than other disorders, and there were also benefits for neck and back complaints, asthma, migraines and vertigo, diabetes, and medically unexplained physical symptoms, as well as other health issues. The benefit was strongest for people with low socioeconomic status and children.

- Urban green spaces have favorable impacts on physical activity, mental health and wellbeing, and social contact, in addition to all the ecological benefits they confer[71]. Mental well-being is associated with both number of green spaces and acreage of green spaces, in a way that supports a dose-response relationship[72].

- Time in outdoor environments reduces stress, according to a 2018 review that looked at heart rate changes, blood pressure changes, and self-report measures[59].

- A 2016 review concluded that, while studies were limited, there was a suggestion of an association between exposure to nature and healthier childhood cognitive development and adult cognitive function[73]. People with dementia who are in care facilities seem to have less agitation if they spend time in a garden[74].

- Green exercise, which is activity in a natural setting, increases self esteem and mood, particularly for people with mental illness. Any sort of green environment has benefit, but the presence of water leads to even greater effects[75]. In a review of 13 trials, 9 of them showed that green exercise had more benefits than indoor exercise when it came to increases in energy and revitalization and decreases in depression, tension, confusion, and anger[76].

- Nature Deficit Disorder, a term coined by Richard Louv, was described based on a concern that limited exposure to the natural world has a profound negative impact on children (and people in general[77]).

5. Emotional Surroundings

It was only from an inner calm that man was able to discover and shape calm surroundings. —Stephen Gardiner

Many aspects of physical surroundings influence Whole Health. The same is true for emotional surroundings. As you talk with Veterans about their emotional well-being, take time to explore what in their surroundings brings them happiness. It will vary from person to person. It may be a particular attribute of a place, or the memories associated with it. Introverts may be more comfortable in surroundings where they have more solitude[78]; extroverts may feel better in groups of people. An activity like climbing might be a joyful experience for one person and a terrifying one for someone else. Mindful awareness can be useful, because we need to know what ours emotional states are and why before we can begin to set emotional surroundings-related goals.

Surroundings influence emotions, but the reverse is also true. Data from thousands of people, compiled by groups like the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, suggests for most people, happiness does not depend significantly on external circumstances. Wealth, in particular, is a poor predictor.[79] More optimistic, altruistic, and generally happy people are less likely to be affected by challenging external circumstances; their emotional health allows them to handle their surroundings and stay healthy. [80][81][82][83]

Mindful Awareness Moment

Noting Emotional Surroundings

Part One. Pause for a moment and assess your current internal emotional state.

- What emotions are you experiencing in this moment?

- Where do you feel those emotions in your body?

- If you had to assign those emotions a color, sound, or texture, how would you describe it?

Part Two. Now, take a moment to assess your emotional surroundings.

- If there are people around you, do you have a sense (through their spoken language or body language, or even based on your intuition) what they are feeling?

- Does your current location allow you to feel at ease, or do you feel tense or as though you have to be on your guard? Why?

- How does this location influence how you feel? Is there anything about this place that influenced the emotional state you identified in part one of this exercise?

What is one thing you could do to make your current location more supportive of positive emotions?

It can be helpful to have a patient take a minute or two to list what makes them happiest. Then, have them list a few sources of unhappiness. Bringing awareness in this simple way can inform how they write their PHP. How might a person bring in more joy, and how might they decrease sources of sadness, fear, and anger? Perhaps more importantly, can they learn to work constructively with their emotional responses to the outside world, whatever those responses might be? That is the focus of many meditation practices.

Here are a few simple suggestions for improving emotional surroundings.

Incorporate more humor

Humor can be an important aspect of healthy emotional surroundings. Even before Norman Cousins described how he used humor for his own healing in 1975, humor was noted for having healing benefits.[84] For example, laughter leads to increases in heart and breathing rates and oxygen consumption, reduced muscle tension, decreased cortisol, and improved immune function.[85][86] Refer to “The Healing Benefits of Humor and Laughter,” for more information.

Bring pets into the picture

One potential contributor to emotional surroundings is the presence of pets and other animals. Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is known to decrease heart rate, pain, anxiety, and depression, and pet ownership is known to have a number of health benefits.[87][88] For more information, check out the “Animal-Assisted Therapies” tool.

Note the influence of media and technology and information overload

We live in an era of information overload (also known as infobesity, infoxication, information glut, data smog…yikes, information overload is happening in this very sentence!). Information overload is linked to poorer memory.[89] In prehistoric times, it served people well to seek and pay close attention to new information; this is not so helpful when we have almost unlimited access to billions of webpages, tweets, texts, and emails.

In the media, the estimated ratio of negative to positive content has been estimated to be roughly 17:1. That is, there are 17 times more negative stories than positive ones in the news.[90] People in the media know they sell more newspapers and have higher ratings if they focus on the negative. As they say, “If it bleeds, it reads.”

The bottom line is when you ask people about their surroundings, remember to ask about their virtual surroundings, which can have a significant effect on stress, mood, and overall perceptions of the environment. Many people find it helpful to periodically do a media/information fast.” Simply unplug for a period of time. For more information, refer to the “Media/Information Fast”.

Assess if person is a highly sensitive person (HSP), and support them accordingly

It has been argued that 10% or so people meet the criteria for being a “Highly Sensitive People” (HSP). Psychologist Elaine Aron described what it means to be a “highly sensitive person” in her 1996 book of that title.[91] HSPs:

- Are easily overwhelmed by intense sensory experiences

- Have trouble with being rushed or needing to make deadlines

- Work to avoid upsetting or overwhelming situations

- Tend to have a heightened esthetic sense

- Like to withdraw after intense times, such as a busy day at work

- Tend to avoid violence, including in movies and TV

More information on highly sensitive people is available at The Highly Sensitive Person website.[92]

When dealing with HSPs, it can be helpful for clinicians to keep the following in mind:

- They are highly attuned to whether or not clinicians are hurried or stressed, and they may limit what they disclose in a visit accordingly.

- Many of them tend to respond to very low doses of medications—both in terms of therapeutic benefits and adverse effects.

- It may help to encourage them to show up 10-15 minutes before they are supposed to see their clinician, if they have a tendency to be late.

- They may be affected strongly by the lighting in offices and examination rooms. Some will ask that you use scent-free hand cleaners.

- They often do well with visualization exercises and guided imagery. It can be helpful to have them envision themselves in a protective “bubble” or “shield” that helps them filter out some of the stimuli feel overwhelming to them.

- HSPs often benefit from encouragement to honor their introvert natures and take a set amount of time as alone time or time just for them each day.

As with all aspects of Surroundings in Whole Health, be creative, and encourage Veterans to ask, at a deep level, what they want and need. For many of them, tapping into their emotional health will not be easy. It might help to look outward at emotional surroundings before looking inward at how traumatic experiences and other factors have had emotional health effects.

Back to Andre

As Andre discussed his PHI and his “Assessing Your Surroundings” form with his Whole Health Coach and his primary provider, he gained insights into what he wanted to put into his PHP. The following are some of the goals he set, with the help of his Whole Health team. Note multiple goals are mentioned here, for the purposes of teaching, but in a typical visit, it is more likely that a Veteran would only choose one of the following to add to the PHP:

- Andre struggles a great deal with clutter, but he does not meet criteria for hoarding behavior. He will explore how to declutter, and he will save enough money to hire a professional organizer or housekeeper to help him, at least for a short period of time.

- Andre’s clinician reviewed information about IEI with him, and they will address his intolerance of strong scents using various mind-body approaches, including hypnosis, which is available at his local VA hospital. He will change positions every hour.

- He is encouraged to take more breaks while he works, and to pause to eat lunch. He will see if he can get a standing workstation for his cubicle.

- His overall toxin exposure seems to be minimal, though he will see about shifting to an apartment that is not so close to someone who smokes. His apartment has relatively clean water and air, and he is not exposed to hazardous chemicals at work, so far as he knows. He is very interested in learning more about low- and high- pesticide foods, and received more information on the Dirty Dozen and Clean Fifteen, which are featured in the “Food and Drink” module.

- Andre agrees there are some simple things he can do to improve his sensory environment at home. He plans to start wearing an eye mask to sleep, and he will consider playing music more often, particularly classical guitar, which he hopes to learn himself someday. He will clean with fragrance-free household products and avoid air fresheners in his house and car, since they give him headaches.

- He will experiment with adding more lighting to his apartment, since he thinks low lighting negatively affects his mood.

- In addition to going to the YMCA, he will go to a nearby park and run twice a week, so that he has more time outdoors.

- On further discussion, Andre does seem to be a “highly sensitive person.” He is very sensitive to his environment, is quite musically inclined, and though he has learned to hide it, is quite shy. You suggest some potential books and websites he can use to learn more. He will give a media fast a try, and you give him the Veteran handout on “Too Much Bad New: How to Do an Information Fast.”

- Andre will follow up with his Whole Health Coach in a week to let her know how it is going with his PHP. He will see his primary in 1-2 months. He was given several other handouts to review, including “An Introduction to Surroundings for Whole Health,” “Workaholism” and “Ergonomics: Positioning Your Body for Whole Health.”

- On further discussion, Andre agrees he is lonely, and at a future visit, he will explore Family, Friends, and Co-Workers as it relates to his self-care.

Why should we think upon things that are lovely? Because thinking determines life. It is a common habit to blame life upon the environment. Environment modifies life but does not govern life. The soul is stronger than its surroundings. —William James

Whole Health Tools

Author(s)

“Surroundings” was written by J. Adam Rindfleisch, MPhil, MD (2018).