Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 4

Chapter 4. Mindful Awareness

In the end, just three things matter:

How well we have lived

How well we have loved

How well we have learned to let go

―Jack Kornfield

What Is Mindful Awareness?

Mindful awareness is central to Whole Health, but the term is not familiar to some people. To understand mindful awareness, it can help to think about what it is like NOT to have it. We have all experienced examples of being on autopilot, not really noticing what is going on around us. After a long day, you arrive home with very little memory of the trip home. You go for a walk with your child, and you do not notice anything about the scenery, because your mind is cluttered with worries about the past and the future (Figure 4-1). You open a bag of chips or a box of cookies, and before you know it, the package is empty, and you hardly noticed, let alone enjoyed, a single bite.

Mindful awareness is the opposite of this. It is the antidote to tuning out or going on autopilot. Mindful awareness is about noticing what is happening when it happens. It is about being aware of the sights and sounds on the drive home, being completely present when you are walking with your child, and tasting every bite of a snack (which might even allow you to feel full sooner, so you eat less). Put another way:

Mindfulness is paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.[62]

Some people add “...and with compassion” to that definition. Practices to cultivate mindfulness are not new; a variety of world spiritual and philosophical traditions address mindfulness and have encouraged people to cultivate it for hundreds—if not thousands—of years.

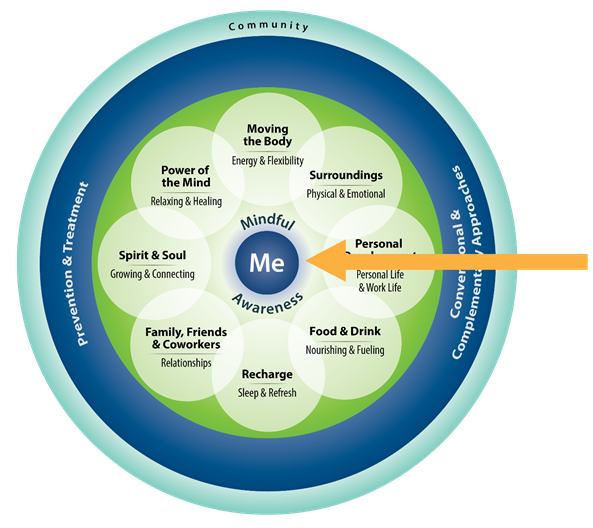

One of the striking things about the Circle of Health is that the “Mindful Awareness” ring immediately surrounds the “Me” at the center of the circle, as noted in Figure 4-2. Just as it is central to the Circle of Health, mindful awareness is central to the entire Whole Health approach. It can inform how we relate to others and how we choose to practice self-care. It is at the root of feeling compassion, and it informs our state of being when we are “in the zone” (in a flow state) with a given activity.[63]

In terms of health, you can imagine how mindful awareness can be important. It influences how we tune into our physical, mental, and emotional states, and it helps us to do so sooner, so that we can prevent a problem from progressing. As the saying by Henry Maudsley goes, “The sorrow that hath no vent in tears, may make other organs weep.” Mindfulness is about noticing something is out of balance before it starts causing major physical symptoms.

Mindful Awareness, Mindfulness, and Meditation

Sometimes the terms mindful awareness, mindfulness, and meditation can be confusing. How do they differ? For the purpose of Whole Health and personal health planning, we use the term mindful awareness interchangeably with formal and informal mindfulness practice. Formal mindfulness includes specific practices, such as a meditation practice of sitting in stillness, usually with the eyes closed, while noticing the sensations of the breath in the body. There are many other examples of formal practices as well. An informal mindfulness practice typically means doing something you are already doing, like washing dishes or petting the cat, with your full attention to the unfolding of experience. Mindfulness means paying attention to the present moment with the qualities of non-judgment, kindness, and curiosity. We make a distinction between mindfulness, a way of being, and mindfulness-based interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

For Whole Health, we use the term mindful awareness to describe both the formal and informal practices of mindfulness, including becoming aware of bodily sensations, our clinging or aversion to these sensations, and how we work directly with mental phenomena and live our lives. At the heart of mindfulness is the idea that we suffer because we do not see the world clearly. The radical promise of mindfulness is clarity, ease, and happiness. Mindfulness-based interventions, like MBSR or the mindfulness classes available at many VA locations, teach Veterans to develop this mindful way of being.

Meditation is an umbrella term that includes mindfulness formal practice as well as other approaches, such as Transcendental Meditation®, Christian contemplative prayer, and others. Broadly, the term meditation refers to a family of self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control. This fosters general mental well-being and the development of specific capacities such as calm, clarity, and concentration.

When Have You Been Most Mindful?

Pause for a moment, and ask yourself the following:

- What circumstances allow you to be at a state of heightened awareness?

- When are you most present?

- When are you most peaceful or calm?

- What makes you optimally focused?

- When are you at your most centered?

These questions are frequently posed during Whole Health courses. Some answers from participants have included the following:

- When I am playing with my kids

- When I am “in the zone” playing a sport

- When I am in the operating room

- When I pray or read scripture

- When I am lost in a good book or movie

- When I am gardening

- When I watch my dog

- When I play my musical instrument

What about the activities you listed causes them to have such a positive effect on you? How can you bring those states of mind with you into other situations? When exploring mindful awareness for yourself and with Veterans, those questions can prove helpful.

Mindful Awareness Research

It is important to emphasize that mindful awareness is an opportunity to be in the wholeness of life, including suffering, joy, peace, unrest, creativity, fullness, emptiness—all of it. Mindful awareness is not merely a technique for coping with a specific problem. Nevertheless, there is an increasingly impressive body of research favoring the use of mindful awareness practices. Western science is now actively studying these techniques (many of them thousands of years old) and their health benefits.

The following list summarizes some of the latest research findings, including those detailed in the “Mindful Awareness” overview on Whole Health Library website.[64] Different studies may have focused on different techniques, but in all of them, mindful awareness was the goal. Note that there have been some recent reviews calling for research in this area to be more rigorous; some mindful awareness-related studies have had methodological challenges.[65]

General Mindful Awareness Research Findings

- Lowers distress in non-clinical populations.

- Has a moderate effect size when it comes to general benefits for primary care patients with an array of different concerns.[66]

- Reduces psychological symptoms in people with cancer, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, tinnitus, multiple sclerosis, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders.3

- Workplace mindfulness training interventions have a number of general benefits, (reduced anxiety and distress, increased well-being) though more research is needed to clarify the effect on burnout levels.[67]

- Seems to increase prosocial behavior (increases the likelihood that a person will help/support others).[68],[69]

- Reduces loneliness and increases social contact.[70]

- May improve sleep.[71]

Physiologic Effects of Mindful Awareness

- Alters brain activity. Long-term meditators have gamma wave oscillations not seen in others. Even people who have just begun meditating in the past 2 months show functional MRI changes.

- Leads to longer-lived relaxation states. Reduces markers of stress, including cortisol, C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, blood pressure, and heart rate.[72]

- Activates the left anterior cerebral cortex and other areas of the brain which are linked to positive mood. Increases activation in brain attention centers.[73]

- Increases gray matter volume in multiple parts of the brain,[74] including the hippocampus.[75]

- Favorably influences T-lymphocyte counts in people with HIV and cancer.[76]

- Lengthens telomeres. The longer these structures at the end of a chromosome are, the lower a person’s risk of chronic illness and mortality. Studies have linked compassion meditation to favorable effects on telomere length. Even just 11 hours of meditation training makes a measurable difference.[77]

- Lowers blood pressure in people with hypertension.[78],[79]

Immune System Effects3

- Enhances immune response to influenza vaccine.

- Stabilizes CD4 counts in people with HIV infection.

- Enhances natural killer cell function and alters interleukin levels.

- Favorably improves some inflammatory markers.18

Mental Health Effects

- In general, mindful awareness seems to decrease the severity of depression and anxiety, though studies with active control groups (groups that do something else besides mindfulness) are less convincing. Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) seems to be quite helpful.[80]

- MBCT is as effective as medications for depression reoccurance prevention.

- MBCT has potential benefit for bipolar disorder as well, but more studies are needed.[81]

- A 2017 meta-analysis found medium effect size for mindfulness in reducing PTSD symptoms. Benefits correlated to the amount of time spent training.[82] Also mitigates the effects of combat stress.[83]

- Assists with the treatment of alcohol and substance misuse, especially when combined with treatment as usual.[84]

- Can reduce consumption of a number of substances of abuse[85] and decrease cravings for them.23

- Has large effects in reducing ADHD core symptoms.[86]

- Appears to be beneficial for depression and anxiety in people with spinal cord injury.10

Pain

- Decreases chronic pain intensity, related disability, and medication use.[87],[88]

- According to a 2017 meta-analysis, leads to a small decrease in chronic pain, as well as less depression and improved quality of life (though more studies needed).26

- Leads to improvements in many fibromyalgia symptoms.[89]

- Has short-term benefits for low back pain.[90]

Other Findings

- Reduces irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms.[91]

- Seems to improve clinician burnout scores, well-being, and the quality of their care.[92]

- A 2019 review of 26 studies of mindfulness training for health care providers found moderate evidence that it improved patient safety, led to better treatment outcomes, and enhanced level of patient-centered care.[93] Another review found it also benefitted anxiety, depression, stress, well-being, and to some degree, burnout.[94] Yet another review specific to nurses found it favorably affected these factors for them as well, along with workplace stress and empathy levels.[95]

- Enhances altruism and allows cultivation of compassion over time.[96]

- Has many benefits as an adjunctive therapy for people with breast cancer.[97]

- May be useful in preventing distracted driving.[98]

- Has the potential to reduce distress in people with chronic dermatologic problems.[99]

- Has initial support (low-quality evidence, per Cochrane) for supporting caregivers of people with dementia.[100]

- MBCT can be helpful with tinnitus.[101]

- Improves cognitive function ans stress in people with dementia.[102]

- Helps with weight loss in overweight and obese individuals.[103]

- Is helpful in palliative care.[104]

Evidence Map of Mindfulness

A 2014 review by VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) summarized the literature with the evidence map featured on the previous page.44

The bubble plot summarizes systematic reviews of mindful awareness interventions published through February 2014. Each circle on the plot represents a clinical condition. The vertical axis represents the size of the literature. If a circle is toward the top, it means more research is available. The horizontal axis represents how effective the intervention seems to be. The farther to the right a circle is, the more the research indicates a benefit for that condition. Colors represent different types of interventions. Green circles indicate that a variety of interventions were used, pink are MBSR, purple are MBCT, and blue are the combination of MBSR + MBCT.

Note that many of the strongest indications of benefit have been noted for people with mental health disorders.

Cultivating Mindful Awareness: Practice Tips

The following tips can be helpful if you are introducing the concept of mindful awareness to someone who is new to it3:

- It is essential to focus on the present moment. Do not get caught up in the past (e.g., regrets or what could have been) or the future (e.g., anxiety, or what could happen down the road).

- Note the word “practice” is often used; people practice mindfulness, and practice is needed to enhance mindful awareness. How much routine practice is needed each day or week is not entirely clear, but a few minutes daily on most days of the week is a good starting place. In a typical MBSR course, learners are encouraged to practice 45 minutes a day.

- People who practice mindful awareness note improved quality of life. They find it becomes easier to work with challenging emotions and thought patterns.

- Cultivating mindful awareness can help you understand/see more clearly.

- Mindful awareness helps you to be more skillful with how you think and react.

- Many techniques involve cultivating compassion and improving how you relate to the world around you, including your interactions with other people.

- There is no one “right” practice, though some devotees may say otherwise. The key is tailoring the practice to the individual. There are many options. Some people prefer movement, while others prefer sitting. Some use a variety of techniques, while others use just one.

- Mindful awareness has a number of health benefits (refer above) but it is best not to think of it as an intervention or therapy for a specific condition, so much as an overall approach that can be beneficial to health in a variety of ways. It is an opportunity to be in the wholeness of life.

- Mindful awareness practices have arisen in diverse religions and spiritual communities throughout human history. Most people find that paying attention to the present moment and observing self are compatible with their religious beliefs. The MBSR course, for example, was specifically created to be neutral in this regard.

- Mindful awareness practice is not easy. It involves a certain amount of discipline and hard work.

- With time, mindful awareness practice evolves into a way of being.

- Safety. Mindful awareness is not for everyone. It should be used cautiously and be guided by a skilled professional for people with severe mental illness, such as psychosis or PTSD. That said, mindful awareness is quite safe.

Metacognition

Metacognition is, put simply, the mind being aware of how it works. For example, consider states of mind you can attain while watching a movie. If cognition—or your usual thinking patterns—are the equivalent of being lost in the movie, to the point where you feel like it is your reality, then metacognition is akin to moving out of that state, into an awareness that you are in the theater, sitting in your seat, caught up in a movie that does not represent your reality. After you experience such moments of broader awareness, you then have the opportunity to choose whether or not to escape back into the movie. The key is that you now consciously have chosen to do so.

Take a moment to explore this more right now.

- What is going on around you as you read this material?

- What other thoughts have been intruding?

- How is your body feeling?

- What is going on with you emotionally?

- What is the temperature of the room?

- What ambient sounds and smells surround you?

- How long has it been since you have taken a break, stood up from a seated position, or rested your eyes?

Mindful awareness is, in part, about becoming more aware of your mind’s patterns. As you come to recognize those patterns, it can be extremely empowering, for then you can consciously choose to make changes.

SOLAR and TIES—Two Mnemonics

These two helpful mnemonics can be applied with any mindful awareness practice.[106] Consider working with them a few times a day. This practice involves taking pauses throughout your day to consciously notice what is going on around you—and inside you—in the present moment. SOLAR is an acronym for

- Stop. Pause what you are doing for a moment.

- Observe. Notice what is happening. Tune into your thinking, emotions, and surroundings.

- Let it Be. Mindfulness is not about striving. You do not have to do something about what you notice. Just notice.

- And

- Return. Go back to what you are doing, hopefully a bit more in the present moment.

TIES is short for the four types of experiences that will come up as you practice mindful awareness. These are:

- Thoughts

- Images

- Emotions

- Sensations

It can be helpful to identify these as they arise when you are doing the SOLAR practice. The more you can catch moments of not being mindfully aware, the more readily your brain will be able to return to that state. Some people find it helpful to think of the TIES items as being equivalent to secretions. Just as our bodies make mucus or saliva, they generate thoughts, images, etc. We can choose simply to observe that happening.

Many clinicians find using the SOLAR/TIES approach helpful as they move from one patient encounter to another. Simply pause for a moment of mindful awareness before you cross a threshold into a clinic or hospital room. This can help you go into the room without carrying anything in from your last encounter or conversation.

Whole Health Tool: SOLAR/TIES Meditation

Whole Health Tool: SOLAR/TIES Meditation

Stop

- Find a quiet space where you won’t be interrupted.

- Set an alarm or timer for 5 minutes (or more). Then forget about time altogether and let the time do the work.

- Sit comfortably, with a straight and relaxed spine, in an alert position. Eyes can be open or closed. Hands can be placed in any position you prefer.

- You can set an intention for this practice, if you would like. Examples: “May I gently keep myself in the present moment.” “May I enjoy the benefits of stillness.”

Observe

- Focus on body sensations. Note your posture and how your feet feel on the floor. Feel your body in contact with your seat.

- Allow breath to enter your nose at a natural rate and depth. Just let your body breathe and note how that feels.

- Moment by moment, take a pause, note your breath, and simply observe whatever arises. If you are having any TIES experiences—thoughts, images, emotions, sensations—simply note them, then return to focusing on your body or your breath.

Let It Be

- For now, just let things be as they are. There is no need to react or change anything. Just witness, whether things are pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant.

- There is no need to strive or judge yourself or the practice. Just notice. Be kind to yourself.

And Return

- If you get caught up in a thought, image, emotion, or sensation, just come back to your breath, to your awareness of your body in the present moment. Return again and again, without judgment, and with kindness to yourself.

- When you are signaled that time is up, take a moment while you are still in stillness to note how you feel. What was this exercise like for you?

This is a useful exercise to try with patients, including those who are relatively new to mindful awareness practices. You can use it in any number of situations throughout the day.

Mindful Awareness Techniques: Mindfulness Meditation

As noted above, there are many methods or situations where you can be mindfully aware. One of the most common methods for achieving mindful awareness practice is through some form of meditation. Not all meditation focuses on this as a goal, but there are many practices where it is given high priority. Examples include the following:

- Seated meditation. If you are trying the exercises as you read this reference guide, you have already done a few seated meditations. This is the image most people have when they think of meditation—sitting on a pillow, legs crossed, holding very still. This is one form of meditation, but by no means is it the only one.

- Body scan meditation. For this, you bring your awareness to various parts of your body. There are many variations as far as how many body parts you focus on and the order in which you focus on them.

- Movement meditation. Many people prefer to stay active because they feel physical activity helps them quiet their minds. Movement meditation can be as simple as walking very slowly while paying close attention to each step, or it can be more elaborate, such as performing tai chi.

- Chant and vocalization. There has been a significant amount of research in the VA supporting mantram meditation, for which the practitioner repeats a word or phrase while focusing on it deeply. Centering prayer, which is a meditation approach that arose within the Catholic tradition, also relies on focusing on a specific word.

- Heart-centered meditations. There are many forms of heart-centered meditations. Examples include compassion meditation, loving-kindness practice, and gratitude practice. Tonglen, a Tibetan meditation, is another. Mindful self-compassion practices have also been gaining in popularity.[107] These practices do seem to have benefits.8

- Mindful eating.40,[108] Many people have tried eating meditations before (e.g., slowly eating a raisin). There are multiple mindful awareness exercises that are based on doing a familiar activity in a deliberate and aware fashion, such as drinking tea, eating one bite of food, or using a stethoscope. An eating meditation is featured in Chapter 8.

Two mindful awareness exercises, focused on seated meditation and breath awareness, and a body scan, are featured next. A loving-kindness meditation is included at the end of Chapter 10, “Family, Friends, & Co-Workers.” Links to other mindful awareness exercises are listed in the Resources section at the end of this chapter. As with any journey of self-discovery, approach mindful awareness with Veterans (and in your own life) with a spirit of curiosity, as though you just traveled to an unfamiliar travel destination and are trying to fully experience it. This approach is often referred to as “beginner’s mind.”

Whole Health Tool: Seated Meditation

Most people, when they think about meditation, tend to envision a seated practice. While this is only one of many ways to cultivate mindful awareness, it is a great place to start. Follow these simple steps:

- Find a comfortable place where you won’t be interrupted.

- Decide how much time you will spend sitting. Start with just a few minutes. Gradually build up over time. 20 minutes is a good initial goal. You may notice benefits/positive changes even after just a few days or weeks.

- Choose a time of day when you will be less likely to fall asleep while practicing. Many people prefer mornings or evenings (or both) but do what works for you.

- You can sit in various ways. Some people sit on the floor, or on a pillow (like a zafu pillow). Others prefer a chair or a meditation bench. Sit comfortably, and use pillows or cushions as needed.

- Soften your gaze (i.e., focus your eyes a few feet in front of you) or close your eyes.

- Choose something to focus on. It may be your breath (as discussed in the Breath Awareness exercise, below), a candle, or even a particular word you repeat.

- Be patient. If you find your mind wandering, gently bring it back and return your focus. Don’t be hard on yourself. Remember, this is about being present non-judgmentally. It is common for this to be challenging at first. Do not let that convince you that you are somehow “a bad meditator;” rather, think of this as an opportunity to gain a new skill.

- When your timer goes off, give yourself a moment to slowly shift out of the meditation.

- Remember, this is a practice. It will get easier with time.

Whole Health Tool: Breath Awareness Exercise

Sit comfortably with your feet planted firmly on the floor. Lengthen your body through your back, neck, and the top of your head. Now, for the next 2 minutes (you can set a timer), turn all of your awareness to your breathing. Without changing the rate or quality of your breathing, simply note the sensation of inhalation, the sensation of exhalation, and the pauses between the two.

Now reflect:

- How easy was it to focus your attention on your breathing for 2 straight minutes?

- What distracting thoughts arose?

- What judgments or evaluations pulled your awareness away from your breathing?

Take 2 additional minutes to repeat the exercise above. This time, when your thoughts wander away from the breath, gently return your attention to your breathing. Judgments may arise — “I can’t concentrate,” or “this is boring.” When this happens, simply notice that this is a thought, and bring your attention back to your breathing. When your mind wanders, be gentle with yourself. Notice if you scold yourself for deviating from the breath. Accept the passing distraction and focus your attention back on the breath.

Now reflect again:

- How did it feel taking 2 minutes just to focus on the breath?

- How easy or difficult was it to maintain your attention on the breath?

- What distracting thoughts and judgments arose?

- How easy or difficult was it to gently bring your awareness back to your breathing?

- How do you feel at the end of this exercise?

If you found it challenging to maintain present-moment awareness of the breath during the last exercise, take heart; the body is a constant ally in remaining grounded in the here and now. Your body feeds you constant updates about your experience of the present moment. Observe your breathing. Note the feeling of your feet on the floor. What signals are arising from your body? Hunger? Thirst? Fatigue? Discomfort? The need to go to the bathroom? What are you seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching? In bringing the awareness to these ongoing status indicators, we are able to maintain presence in the current moment.

Whole Health Tool: Body Scan

Whole Health Tool: Body Scan

This exercise invites you to sequentially tune in to the experience of various parts of the body. The goal is to bring full awareness to the status of the body, not to change the status of the body. You may benefit from practicing in relative peace and quiet with your eyes closed in the beginning, but ultimately this practice will be useful to you no matter your surroundings or circumstance. This exercise can take 5 minutes or more than an hour, depending on how you choose to practice and your familiarity with the technique.

- Find a comfortable position. The first few times you do this practice, try lying on your back with your eyes closed.

- Take 5 slow, deep breaths. Feel the rise of the abdomen as you breathe in, and the fall of the abdomen as you breathe out. Imagine you draw the breath in through the soles of the feet and release the breath out through the top of the head. Continue to breathe slowly and deeply throughout the exercise.

- Note the sensations in your body as a whole. What information is your body giving you? What does your body ask you to recognize?

- Now begin the sequential survey of each body area.

- Begin with the toes of the left foot. Note the sensations they are sending you. Do you feel cool air, a soft blanket, a scratchy sock, or a confining shoe? Perhaps you don’t feel anything. This is okay; simply spend a few moments in the experience of not feeling anything. Once you have fully experienced the status of your left toes, take a deep breath, and let go of the left toes. Let the sensation from this body area fade away.

- Next move to the sole of the left foot. Note the sensations it is sending you. Note the lack of sensation if that is the case. Once you have fully experienced the status of the sole of the left foot, take a deep breath, and let go of the sole of the foot. Let the sensation from this body area fade away.

- Continue the somatic evaluation of each body area with your full concentration. From the sole of the left foot, transition to:

- Top of the left foot

- Ankle

- Shin

- Calf

- Knee

- Thigh

- Hip

- Pelvis

- Right lower extremity (in the same manner as the left)

- Return to the pelvis

- Abdomen

- Lower, middle, and upper back

- Chest

- Left fingers

- Left hand, wrist, forearm, upper arm, shoulder

- Right upper extremity (in the same manner as the left)

- Neck

- Face

- Scalp

- Crown of the head

- Once you finish with an area, take a deep breath and let that area go. If your concentration lapses, take a deep breath and pick up where you left off.

- Close the practice by returning to the breath. Take 5 deep breaths, noting the rise and fall of the abdomen. Imagine inhaling through the soles of the feet and exhaling through the top of the head.

You can shift the timing of the meditation by focusing on more or fewer sections or parts of the body during the scan.

For a voice-guided body scan practice, visit the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Mindfulness Meditation Podcast Series.

Mindful Awareness in the VA

Mindful awareness training is becoming increasingly common in the VA. In fact, as noted in Chapter 14, some of the ways to cultivate mindful awareness, such as meditation training and tai chi, are now offered in VA facilities nationwide as part of the Veteran benefits package. VA sites are still trying to figure out the logistics of this. One option is to use Telehealth to bring training to more remote areas. A 2017 review of 16 studies concluded that Web-Based Mindfulness Interventions may be helpful in alleviating physical symptom burdens, even when training is asynchronous (not taught live), as in a web-based course.[109]

Medical research is only beginning to scratch the surface regarding the power mindful awareness has to favorably improve health and well-being. When you are doing personal health planning, be “mindful” of mindful awareness as something you can bring in to the Personal Health Plan (PHP).

Mindful Awareness Resources

Websites

VA Whole Health and Related Sites

- Mindfulness Awareness videos. From the VHA Mindfulness Toolkit created by the Greater Los Angeles VA. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/mindful-awareness.asp

- What is Mindfulness?

- Why Mindfulness for the VA?

- Four Ways to Cultivate Mindfulness

- Beginning a Mindfulness Practice

- Mindfulness and Compassion

- Guided Meditation and Audio Files. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/mindful-awareness.asp

- Introduction to Meditation with Dr. Greg Sherpa (5 minutes)

- Grounding Meditation (5 minutes)

- Mindfulness of Breathing Meditation (10 minutes)

- Mindfulness of Sounds Meditation (10 minutes)

- Compassionate Breathing Meditation (10 minutes)

- Loving Kindness Meditation (10 minutes)

- Body Scan Meditation (15 minutes)

- Body Scan with Loving Kindness Phrases (15 minutes)

- An Intro on Mindfulness and Using the Personal Health Inventory (22 minutes)

- Paced Breathing (7 minutes)

- Mental Muscle Relaxation (5 minutes)

- Mini Mental Vacation (7 ½ minutes)

- Evidence Map of Mindfulness. Compilation of systematic review data by VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D). https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/cam_mindfulness.cfm

- Veterans Whole Health Education Handouts. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-handouts/index.asp

- An Introduction to Mindful Awareness

- Mindful Awareness Practice in Daily Living

- Precautions with Using Mindful Awareness Practices

- Mindfulness facilitator training programs are also available. Contact Greg Serpa, John.serpa@VA.gov

- STAR Well-Kit. War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/STAR/

- Introduction, Part 3: Veterans Explain How Guided Meditation Enhances Well-Being

- Ben King—Deep Breathing (Veteran describes his experience)

- Patrick Crehan—Mindfulness Meditation (Veteran describes his experience)

Whole Health Library Website

- Mindful Awareness. Overview. Excellent review of latest research. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/mindful-awareness

- Bringing Mindful Awareness into Clinical Work. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/bringing-mindful-awareness-clinical-work <>Mindful Awareness Practice in Daily Living. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/mindful-awareness-practice-daily-living

- Practicing Mindful Awareness with Patients: 3-Minute Pauses. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/practicing-mindful-awareness-patient

- Going Nowhere: Keys to Present Moment Awareness. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/going-nowhere-keys-present-moment-awareness

- Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Low Back Pain. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/mindfulness-meditation-for-chronic-low-back-pain/

Other Websites

- Dartmouth College Student Wellness Center Mindfulness & Meditation. A variety of guided meditation exercises, as well as others for relaxation and guided imagery. https://students.dartmouth.edu/wellness-center/wellness-mindfulness/mindfulness-meditation

- Foundation for Active Compassion Media. https://foundationforactivecompassion.org/media/category/listen/

- Free Mindfulness Project. Instructors have donated recordings. http://www.freemindfulness.org/download <>Insight Meditation Society. A variety of talks and meditations. http://www.dharma.org/resources/audio/

- Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy information. https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/mindfulness-based-cognitive-therapy

- UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center Guided Meditations. Several in Spanish. http://marc.ucla.edu/body.cfm?id=22

- University of California San Diego Center for Mindfulness. https://medschool.ucsd.edu/som/fmph/research/mindfulness/programs/mindfulness-programs/MBSR-programs/Pages/audio.aspx

- University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness Videos. https://community.cfmhome.org/c/video-room

- University of Washington Addictive Behaviors Research Center Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention Resources. Recordings at the bottom of the page. https://www.mindfulrp.com/for-clients

- University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Mindfulness in Medicine. https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/mindfulness/

- Mindfulness Resources. https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/mindfulness/resources/

- Mindfulness Meditation Podcast Series. https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/mindfulness-meditation-podcast-series/

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Healthy Minds. A leader in mindfulness research. https://centerhealthyminds.org

- The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society Guided Practices. http://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/recordings

Apps and Monitoring Software

The popular phone apps listed below are free, although most have in-app purchases or memberships available. Find them by searching online or in your device’s app store. See also Chapter 12, “Power of the Mind,” for a list of related apps.

- 10% Happier

- Aura

- Breethe

- Buddhify

- Calm

- Headspace

- iMindfulness

- Insight Timer

- Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics

- Smiling Mind<;li>

- MyLife Meditation by Stop. Breathe. Think

Books

- A Clinician's Guide to Teaching Mindfulness: The Comprehensive Session-by-Session Program for Mental Health Professionals and Health Care Providers, Greg Serpa (2015)

- Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body, Daniel Goleman (2017)

- Beginning Mindfulness: Learning the Way of Awareness, Andrew Weiss (2004)

- Calming Your Anxious Mind: How Mindfulness and Compassion Can Free You from Anxiety, Fear, and Panic, Jeffery Brantley (2007)

- Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn (2006)

- Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness, Jon Kabat-Zinn (2005)

- Happiness: Essential Mindfulness Practices, Thich Nhat Hahn (2005)

- Leave Your Mind Behind: The Everyday Practice of Finding Stillness Amid Rushing Thoughts, Matthew McKay (2007)

- Mindful Movements: Ten Exercises for Well-Being. Thich Nhat Hanh (2008)

- Mindfulness in Plain English, Bhante Henepola Gunaratana (2002)

- The Mindful Way Through Anxiety: Break Free from Chronic Worry and Reclaim Your Life, Susan Orsillo (2011)

- The Mindful Way Through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness, Mark Williams (2007)

- The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation, Thich Nhat Hahn (1999)

- The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle (2004)

- Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness: Practices for Safe and Transformative Healing, by David A. Treleaven (2018)

- Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki (2011)

- Also refer to the meditation resources at the end of Chapter 12, “Power of the Mind”

Other Resources

- CDs

- Body Scan: Managing Pain, Illness and Stress with Guided Mindfulness Meditation, 2nd edition, Vidyamala Burch (2008)

- Guided Mindfulness Meditation (3-part series), Jon Kabat-Zinn, (2004)

- Mindfulness Meditation for Pain Relief: Guided Practices for Reclaiming Your Body and Your Life, Jon Kabat-Zinn (2010)

- Living Without Stress or Fear: Essential Teachings on the True Source of Happiness, Thich Nhat Hahn (2009)

- Road Sage: Mindfulness Techniques for Drivers, Sylvia Boorstein (2006) Audiobook CD

Special thanks to Adrienne Hampton, MD, who wrote the original Whole Health Library materials on Mindful Awareness that provided inspiration for much of the content of this chapter. She created the “Body Scan” tool for this chapter, as well as the “Mindful Movement” tool featured in Chapter 5. Also, thanks to Greg Serpa, PhD, who assisted with the section about defining mindful awareness, mindfulness, and meditation.

References