Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 6

Chapter 6. Surroundings: Physical & Emotional

The mountains are calling and I must go.

―John Muir

The Importance of Healthy Surroundings

We do not live in a vacuum; health is not just what is going on inside us. Our surroundings have a significant impact on who we are and how we feel. We know this instinctively and increasing numbers of studies are giving us a better understanding of how our surroundings affect our health.

Epigenetics is the study of how the environment interacts with our genetic information to influence which genes are expressed and how.[199] In identical twins who have the same genome, one twin may show a certain trait or have a particular problem, while the other does not. Why? Their environment. One twin may have had more sun exposure, or more exposure to tobacco smoke. One twin may have been more active, or less stressed, or exposed to different toxins at work or at home. The possibilities for how differences in environment might have affected them are practically endless. The findings of epigenetics studies can be cause for optimism.[200] If our surroundings can cause changes in our gene expression, that means we can take steps to favorably influence the process. How might we do that?

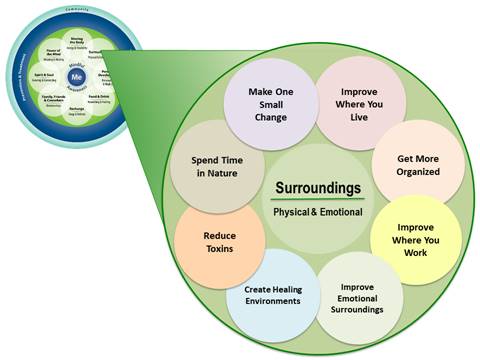

The skill-building courses for Veterans, introduced in the previous chapter, were designed to help learners zero in on specific “subtopics,” which could be incorporated into Personal Health Plans (PHPs). Figure 6-1 shows the subtopic circles for Surroundings. All of these topics are discussed in this chapter. Note that there is a “Make One Small Change” circle to remind Veterans that even small changes matter. It also allows them to come up with their own ideas if they do not find something they want to work with in the other circles.

Questions to Ask About Surroundings

The following questions represent a place to start when you are talking to people about their surroundings. There are some excellent guides to taking an exposure history, including a good summary in a 2002 article by Marshall and colleagues.[201],[202] For more detailed tools for assessing a person’s surroundings using questionnaires or surveys, refer to the Resources at the end of this chapter.

- Where do you live?

- What is your living situation (house, apartment, homeless, etc.)?

- Is your living situation stable?

- Do you have utilities in your living space (heat, electricity, air conditioning)?

- Do you feel safe there? If not, what is unsafe?

- Who lives with you?

- Do you have any pets?

- If you could change some things in your surroundings, what would they be?

- Do you live where you want to live?

- Where would you live if you could choose to live anywhere?

- Is your community or neighborhood safe?

- Do you live near any green spaces, like parks?

- How often do you spend time in nature?

- Are you dealing with any pests, like bedbugs, roaches, or mice?

- Do you have clean water?

- Are you exposed to air pollution?

- Do you ever feel like your health is better when you are away from home for a while?

- Does anything happen at work that harms your health?

- Have you had any injuries at work?

- Are you exposed to things like lead, radon, cigarette smoke, or asbestos?

Eight Aspects of Surroundings

The next sections cover seven aspects of surroundings—home, work, neighborhood, emotional surroundings, time in nature, and healing environments—in greater detail. To learn even more, go to the “Surroundings” overview.

1. Home

There is a reason why many clinicians consider home visits invaluable. According to the National Center for Healthy Housing, a healthy home is all of the following[203]:

- Dry. Keeping the home dry prevents problems with mites, roaches, molds, and rodents.

- Clean. This also decreases pests and risk of infection. Clutter can be a cause of health conditions (e.g., increased fall risk) and also a sign of them (e.g., hoarding behavior can indicate mental health problems). 5% of people meet the criteria for hoarding; their living spaces are cramped, unsanitary, and potentially dangerous. In half of hoarders’ homes, they do not use their sink, tub, stove, or shower because those items are full of accumulated objects.[204] Hoarding often begins when a person has a traumatic experience in their teen years, and 75% of the time it is linked with other mental health conditions, including obsessive compulsive disorder.6 Squalor, in contrast to hoarding, involves accumulation of refuse (garbage) in the home. People who live in squalor tend to be elderly and carry diagnoses of dementia, alcohol use disorder, or schizophrenia.[205]

- Pest-free. Bedbugs, poisonous spiders, roaches, rats, and mice can all cause health problems. Pesticide residues can pose risk, so dealing with pests must be done properly.

- Safe. This includes reducing fall risk, as well as preventing fires and poisoning. It can also tie into violence in the home. It is important to ask about the presence of weapons in the home since this can be associated with increased suicide and homicide risk.

- Contaminant-free. Radon, asbestos, lead, tobacco smoke, and carbon monoxide can all be problematic. Remove shoes when coming into the home to reduce toxins that are brought in from outdoors. Use nontoxic cleaning products.

- Ventilated. This helps with lung health and air quality.

- Maintained. This ties in with all the above. A better-maintained home is a healthier home in terms of pests and safety, not to mention aesthetic appeal. This also influences health, as discussed below.

Homelessness

When considering home environment, always ask about homelessness. As of 2018, there were 553,000 homeless people in the U.S.[206] As of 2019, there are about 37,000 Veterans homeless on any given night.[207] Male Veterans are 30% more likely to be homeless than men who are not Veterans.9 On a positive note, the VA has reduced the number of homeless Veterans by nearly 50% since 2010, and in 2019, there was a 2.1% decrease in the number of homeless Veterans in the U.S., with 793 more Veterans having shelter.9 Not surprisingly, homelessness is associated with unmet health needs, higher emergency department use, and poorer quality of life. Veterans and their support team can call 1-877-4AID-VET to reach the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans.

2. Work

Important elements of work environment include ergonomics, safety at work, and the overall “feel” of the workplace. Stress[208] and sedentary behaviors[209] related to commuting may also be factors to consider, along with how much a person is working. Active commuting (e.g., biking or walking to work) markedly decreases mortality, including mortality from cancer and heart disease.[210] A significant portion of people’s lives is spent at work; the average American has an 8.8 hour workday.[211] The amount of control a person has at work and whether work demands are high or low both affect risk of death. A 2016 study of nearly 2,400 workers found that those in low-control, high-demand jobs had a 15.4% increase in odds of mortality, compared to people with low-control, low-demand jobs. Interestingly, people with high control, high-demand jobs had a 34% decrease in mortality risk compared to those with high-control jobs with low demand.[212] There is also a correlation between coronary heart disease risk and having a high-effort, low-reward job. Meaningful work correlates with reduced depression (though relationship with anxiety and stress was less clear).[213] Lower levels of job stress correlate with lower rates of insomnia.[214]

When exploring surroundings at work, begin by asking about whether or not a person has a job.[215] Honor that it may be formal employment, or they may work all day as a caregiver to a family member, etc. Unemployment increases mortality risk by 63% and contributes significantly to chronic illness.[216] Encourage Veterans to make use of vocational rehabilitation services when they are available. Be sure to consider ergonomics[217] and the risks of prolonged sitting for desk work as well.11 Links to websites with information on how to help workers harmonize with their jobs are listed in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

3. Neighborhood

One’s general living circumstances also influence health. Some examples include the following:

- Risk of crime and violence in one’s building or neighborhood is an important consideration. A 2017 review found that exposure to community violence influences several areas of physical health.[218]

- Perceived neighborhood safety is closely linked to older adults’ health and well-being.[219]

- People from rural areas may have challenges accessing various care services.

- Living next to green spaces, such as parks is important, as described in the “Time in Nature” section later in this chapter. For instance, access to nature seems to be tied to less violence in urban settings.[220]

4. Emotional Surroundings

Emotional surroundings can include anything that influences emotional well-being, including emotional abuse and intimate partner violence. Always consider the possibility of domestic violence and elder abuse. Over 35% of women and 29% of men have experienced rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.[221] 7-12% of female Veterans have experienced intimate partner violence,23 and intimate partner violence perpetration rates are much higher for active service military personnel and Veterans with PTSD and depression.[222] One study of 407 post-9/11 Veterans found that 2/3 of both men and women in the sample had experienced intimate partner violence in the past 6 months, primarily in the form of psychological aggression.[223] In addition to physical injury, mental health sequelae are likely to occur, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, psychosis, self-harm, psychosomatic conditions, and decreased ability to trust others.[224] Veterans in your care could be surviviors of abuse, or they may be perpetrators of this violence. Information related to military sexual trauma is included in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

An important aspect of working with emotional surroundings is simply recognizing one’s emotional state on a regular basis; mindful awareness of emotions is important. More optimistic, altruistic, and generally happy people are less likely to be affected by challenging external circumstances; their health is likely to be better in general, and they are much more resilient.[225],[226],[227]

Some ways to enhance positive emotional surroundings include:

- Incorporate more humor. Laughter leads to increases in heart and breathing rates and oxygen consumption, reduced muscle tension, decreased cortisol, and improved immune function.[228],[229] Refer to the “The Healing Benefits of Humor and Laughter” Whole Health tool.

- Spend time with animals. Consider getting a pet. There is good data supporting animal-assisted therapies.[230] Check out the “Animal-Assisted Therapies” Whole Health tool.

- Be cautious about the influences of information overload, especially from negative media sources. In the media, the estimated ratio of negative to positive content has been estimated to be roughly 17:1.[231] Consider a media fast, as described in the “A Media/Information Fast” Whole Health tool.

- Consider mind-body practices to foster relaxation, compassion, and/or happiness. Examples are featured in Chapter 12. A gratitude practice can also prove beneficial, as discussed in Chapter 7.

Highly Sensitive People

It can also help to assess a patient’s level of sensitivity. In the psychology literature, there is discussion of the “highly sensitive person.” Psychologist Elaine Aron described what it means to be a “highly sensitive person” (HSP) in her 1996 book of that title.[232] Highly sensitive people (HSPs) exhibit the following qualities:

- Are easily overwhelmed by intense sensory experiences

- Have trouble with being rushed or needing to meet deadlines

- Work to avoid upsetting or overwhelming situations

- Tend to have a heightened aesthetic sense

- Like to withdraw after intense times, such as a busy day at work

- Tend to avoid violence, including in movies and TV

- May be quite intuitive

When working with HSPs, or if you are one yourself, it can be helpful as a clinician to keep the following in mind:

- They are highly attuned to whether or not clinicians are hurried or stressed, and they may limit what they share during a visit based on how rushed a clinician seems.

- Many respond to very low doses of medications—both in terms of therapeutic benefits and adverse effects. As the saying goes, “Start low, and go slow.”

- It may help to encourage them to show up 10-15 minutes before they are supposed to see their clinician if they have a tendency to be late.

- They may be affected strongly by the lighting in offices and examination rooms.

- They often do well with visualization exercises and guided imagery. It can be helpful to have them envision themselves in a protective “bubble” or “shield” that filters out some of the stimuli that overwhelm them.

- HSPs often benefit from encouragement to honor their introverted natures and take a set amount of time as “alone time” each day.

5. Climate and Ecology

Health conditions related to climate and ecology might include whether there is sufficient sunlight to make vitamin D, risk of exposure to excess heat or cold, and the presence of allergy triggers and toxins. Consider exposure to cigarette smoke (including second hand). Air pollution (especially for people with breathing problems), food toxins, sanitation, and water pollution may all be relevant. If needed, a person can learn about their tap water (there is more information in the Resources list at the end of this chapter) or have well water sampled. Some people are more prone to seasonal affective disorder, too.

Global climate change poses a significant potential health risk as well.[233],[234] Taking action to ensure a healthy global environment is also contributing to Whole Health on a very large scale.

We are exposed to thousands of toxins. A 2011 systematic review concluded that 4.9 million deaths (8.4% of the deaths worldwide) and 86 million “disability adjusted life years” were due to environmental exposures.[235] It can help to focus on reducing total chemical burden, by reducing just one or a few exposures at time; trying to reduce too many things at once can be overwhelming. Encourage people to minimize exposure to smoke, car exhaust, and farm chemicals. Avoid toxins like the bisphenol A (BPA) in beverage containers and consider using more “green” cleaning products. Do as much as possible to ensure food is safe as well. The Resources at the end of the chapter offer additional details.

Be sure to ask Veterans specific questions related to the following:

- Exposure to Agent Orange or other chemical weapons

- Presence of shrapnel in the body

- Past encounters with radiation

- Risks related to biological weapons

6. Detoxification

Detoxification, or “detox,” refers to a large variety of methods that are used with the intent of removing toxins from the body.[236] These methods are frequently brought up by patients. Detox has been defined by complementary therapies researcher Edzard Ernst as follows[237]:

In alternative medicine, ‘detox’ … describes the use of alternative therapies for eliminating ‘toxins’ (the term usually employed by proponents of alternative medicine) from the body of a healthy individual who is allegedly being poisoned by the by-products of her own metabolism, by environmental toxins or (most importantly) by her own over-indulgence and unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes and food).

Many of these approaches are not new; Ayurvedic medicine has been using Panchakarma, an array of detoxification techniques (sweating, oil massage, purgatives, enemas, bloodletting, nasal irrigation, and fasting), for thousands of years. 92% of naturopaths in the U.S. use some form of detoxification in their practices.[238] There are numerous books available in the popular press that focus on detox methods.40

Popular Detoxification Methods

There are a number of detox methods available. Research supporting their use is limited.

- Detox supplements. These include a number of different herbal remedies and other compounds, including burdock, chlorella (green algae), cilantro, clay, dandelion root, glutathione, milk thistle, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), and spirulina. They are generally viewed as safe, but data supporting their use is limited, with the exception of perhaps milk thistle for some liver concerns and NAC, which is used in conventional medicine for acetaminophen overdose.[239],[240]

- Chelation therapy. Chelation involves the binding of a particular chemical compound to an ion (e.g., iron, mercury, or lead) to negate its toxic effects. Succimer and Dimaval, used in EDs to treat heavy metal poisonings, are examples. Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) is a chelating agent that is FDA-approved for use with lead, mercury, arsenic, bismuth, copper, and nickel toxicity. Chelation therapy is thought to work in part by pulling calcium out of calcium deposits in blood vessels. Intravenous EDTA chelation is not formally approved for use in the treatment of vascular disease, Alzheimer’s, or autism, but some practitioners use it as a “complementary” therapy for these conditions.[241] Prior to 2013, systematic reviews of EDTA chelation did not find overall benefit.[242] However, in 2013, EDTA chelation therapy received renewed attention when the Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) concluded that EDTA modestly reduced risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69-0.99). The TACT 2 trial is now underway.[243]

- Colonics. A colonic is, in essence, a therapeutic enema. Water and other substances, ranging from fiber and herbal remedies to probiotics or coffee, are instilled into the colon. Proponents of the practice suggest that it helps to decrease inflammation, thereby making the intestines less permeable to larger, potentially more allergenic molecules.[244] Recent reviews have failed to find substantive research supporting the use of this practice, though groups like the International Association of Colonic Hydrotherapists still advocate its use.[245] Side effects include nausea, diarrhea, bloating and cramping; rarely people can experience bowel perforation, infection, and electrolyte changes.[246]

- Sauna therapy. Sauna therapy has been used for centuries, especially in Scandinavia. Thermal stress can increase heart rate, enhancing cardiac output and decreasing peripheral vascular resistance.[247] Circulation to muscles, kidneys, and other organs increases. Effects on metabolic rate and oxygen consumption are comparable to moderate exercise. Norepinephrine output increases, but cortisol does not, unless cold-water immersion occurs after the sauna. Beta-endorphins likely provide pain-reducing and pleasurable effects. Saunas also lead to muscle relaxation and aldosterone secretion. A 2015 review noted that sauna bathing was linked to a reduced risk of sudden cardiac death, fatal coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality.[248] Other studies have shown additional benefits, including improved respiration in pulmonary disease, improved blood pressures, reduction in depressive symptoms, reduced dementia risk, reduced venous thromboemboli (blood clots), and improvements in some chronic pain measures.49,50,[249]

- Detox diets purport to flush out the body and support toxin-removal efforts of the liver, kidneys, and lymphatics. Many of these diets feature some sort of fast or require people to limit the range of what they eat and drink. For instance, people might only be allowed to have water, organic fruit/vegetable juice, and soups. Or they may only consume a lemonade-like drink, a laxative tea, and electrolytes. Often the diet’s creator will sell products used for the diet. There is little evidence to support the use of these diets.

Use and Safety

It is challenging to know whether or not to use various detoxification methods. People will use them if they believe their dental amalgams are contributing to health conditions, or if they feel they have “disseminated fungal overgrowth.” These diagnoses are controversial and not widely accepted in the medical community. People may also try them for skin problems, chemical intolerances, allergies, cognitive impairment, and many other indications. There are differences in opinion among different types of clinicians about which techniques to use. As is appropriate to your scope of practice, become familiar with the research so you can offer guidance. You will have to decide how to balance between research findings, costs, and safety. (Other suggestions are featured in the “Tips from Your Whole Health Colleagues” section, below.)

- Detox supplements seem safe overall but are of unclear efficacy. Remember that oral glutathione is not processed into a usable form in the gut, so it is not a reasonable choice.

- Chelation, noting the risks, should only be done under close supervision by someone who is well-trained. Chelation therapy is known to have some complications, including injection site irritation and nausea/vomiting, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, hypocalcemia, renal failure, and (very rarely) death.39

- Colonic therapists are often members of the International Association of Colonic Hydrotherapists. Evidence of benefit is limited. People will often receive these on a regular basis. Colonics rarely have adverse effects. These include nausea, diarrhea, bloating, and cramping.39 More serious risks include bowel perforation, infection, and electrolyte changes. There are case reports of significant adverse effects, such as arrhythmias, from coffee enemas.39

- Sauna therapy. This can be used as tolerated, provided it is safe. Many people will sauna for 15-60 minutes, but there are many different recommendations around ‘dose.’ Start out at a lower amount of time and gradually increase. Sauna therapy is safe, so long as people are able to withstand the associated increases in metabolic rate, which are comparable to moderate exercise. Fainting due to low blood pressure or dehydration is possible. It is perhaps safest to sauna with others. Do not drink alcohol prior to taking a sauna.

- Detox diets tend to last for 7-10 days, though some may last for longer. Many of the more popular ones require purchasing a specific book or dietary supplements. Be cautious about how sales pitches and anecdotes can overshadow actual scientific knowledge. To avoid food toxins, it is useful to at least steer clear of the “Dirty Dozen” foods identified by the Environmental Working Group as being high in pesticides even after washing (as compared to the “Clean 15,” which are relatively safe)[250]:

|

The Dirty Dozen (Most pesticide residues) |

The Clean 15 (Least pesticide residues) |

|

1. Avocados 2. Sweet corn 3. Pineapples 4. Onions 5. Papayas 6. Frozen sweet peas 7. Eggplant 8. Asparagus 9. Cauliflower 10. Cantaloupe 11. Broccoli 12. Mushrooms 13. Cabbages 14. Honeydew melon 15. Kiwis |

Tips from Your Whole Health Colleagues

- If someone is asking about detoxification, weigh what you know about efficacy against safety data. The better you know the person, the better you can advise him or her.

- Remember there is a strong financial gain for many of those who advocate detoxification techniques. In particular, many focus their marketing on people with cancer. Note that the research for many techniques is sparse.

- A very limited number of Integrative Health clinics offer chelation or colonic therapies. Know who offers these therapies in your area.

- Some reasonable suggestions. The following are some simple approaches to detoxification that you might suggest:

- Drink fluids. Unless contraindicated for medical reasons, a standard detox practice that makes sense is to have people push fluids. 8-10 glasses of water a day is a reasonable goal for most people.

- Focus on a healthy diet. It is safe to eat a predominantly fruit and vegetable diet for several days. Always pay attention to overall nutritional needs.

- Hydrotherapy is another safe and easy approach to follow. Hot and cold showers and baths can be helpful.

- Exercise. In addition to its many other health benefits, exercise is an excellent sudorific (i.e. it promotes detoxification via sweating). Glutathione, a compound involved in many of the body’s detoxification chemical pathways, increases in muscle cells during exercise.

- Slow down and relax. Take breaks. Enjoy yourself along the way.

- Sleep enough. Remember that one role of sleep is to allow the brain to remove toxins and waste products.

- Keep in mind that a detox might also involve removing oneself from toxic emotional environments, or from information overload. Focus on positive emotions. Gratitude, optimism, and resilience can serve as a sort of “emotional detox.” Links to information on how to do a media fast are listed in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

- Spend time in nature. Fresh air and natural beauty have few contraindications.

7. Time in Nature

There is good support in the medical literature for spending time in parks, gardens, and other areas of natural beauty. Here are some examples of some relevant studies:

- Data from the U.S. Nurses’ Health Study found those with the highest quintile of “cumulative average greenness” near their home had a 12% lower rate of all-cause nonaccidental mortality than nurses in the lowest quintile.[251] A review of 12 studies that involved millions of people around the world found a correlation with “higher residential greenness” and mortality from cardiovascular disease.[252] All-cause mortality is also favorably affected.[253]

- A study of over 345,000 people found that prevalence of 15 out of 24 different “diseases clusters” was lower if they lived within a 1 kilometer of a green space.[254] Depression and anxiety were affected more favorably than other disorders. Neck and back complaints, asthma, migraines and vertigo, diabetes, and medically unexplained physical symptoms also improved. The benefit was strongest for people with low socioeconomic status and children.

- Urban green spaces have favorable impacts on physical activity, mental health and well-being, and social contact, in addition to all the ecological benefits they confer.[255] A 2019 study indicated that older adults who live closer to natural environments have better physical functioning as they age.[256] People seem to learn better in natural settings too.[257]

- Time in outdoor environments reduces stress, according to a 2018 review that looked at heart rate changes, blood pressure changes, and self-report measures.[258]

- A 2016 review concluded that, while studies were limited, there was a suggestion of an association between exposure to nature and healthier childhood cognitive development and adult cognitive function.[259] People with dementia who are in care facilities seem to have less agitation if they spend time in a garden.[260]

- Green exercise, which is activity in a natural setting, increases self-esteem and mood, particularly for people with mental illness. Any sort of green environment has benefit, but the presence of water (“blue space”) leads to even greater effects.[261] In a review of 13 trials, 9 of them showed that green exercise had more benefits than indoor exercise when it came to increasing energy and revitalization and decreasing depression, tension, confusion, and anger.[262]

- A 2020 systematic review concluded there is a positive association between green space exposure and sleep, both in terms of quality and quantity.[263]

- Ecotherapy, which involves interacting with nature to enhance healing and growth, is gaining popularity. It has been found to improve recovery times, reduce distress, benefit PTSD, reduce substance use disorder, and enhance well-being,[264] among many other benefits. Forest bathing and wilderness therapy are some popular examples of ecotherapies.

8. Healing Environments

Various groups have worked to identify all the elements that can make a specific space as healing as possible.[265] Consider your local health care facility. Are clinics and hospitals healthy places to be? Are noise levels, art, colors, and smells conducive to health? Are these facilities doing all they can to reduce negative impacts on the environment?[266] Environmental design involves shifting the attributes of a space so that it is as likely as possible to promote healing. It can inform the design of health care facilities, and it can also guide how we furnish or decorate our homes or workspaces.

Whole Health Tool: Healing Spaces and Environmental Design

Whole Health Tool: Healing Spaces and Environmental Design

What Is It? 54 , 67

Our sensory environment has a significant impact on health. Light levels affect mood and sleep quality.[267] Loud noises can influence blood pressure and heart rate for hours after a person hears them. Music can have a variety of effects.[268] It can calm people down or arouse them, and it influences dopamine release in the central nervous system. Choosing the right color can change the feel of a space; cool tones slow the autonomic nervous system, while warm tones activate it.[269] Art—particularly art that features the natural world (versus abstract art)—improves patient outcomes.[270] Environmental design draws from evidence-based findings regarding what aspects of a health care environment can enhance health, above and beyond what is “done to” patients during clinician encounters, tests, and procedures. Important elements include smell, art, color, light, sound, music, nature, and temperature.

How It Works

Our senses connect the outer world with our central nervous systems, and different sensations can be arousing or calming. Intentionally choosing how to design a room, office, or clinic based on what we know about environmental design can lead to healthier emotional states, better sleep, less stress, and greater comfort.

How to Use It

If given a bit of encouragement, people often will share a number of great ideas about how to improve their sensory surroundings at home and work. Strategies to incorporate into a Personal Health Plan (PHP) may include one or more of the following:

- Buying light-opaque curtains or a sleep mask

- Wearing earplugs to bed

- Painting a room or adding more art to the walls

- Buying an electric heater or fan to adjust temperature (or provide some white noise)

- Purchasing a plant or enjoying time outside in nature

- Opening windows

- Having smokers cut back and/or smoke outdoors

- Cleaning with more natural household products that are free of fragrances

- Using specific aromatherapies

Places to find more detailed suggestions are listed in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

When to Use It

These elements should be considered in all spaces—one’s home, at work, and in health care settings.

What to Watch Out for (Harms)

These approaches tend to be quite safe.

Tips from Your Whole Health Colleagues

- In order to modify your surroundings to be optimally healing, you first need to take note of them. It can be helpful to move through the different parts of your clinic or hospital (or home or office) as though you are a patient, taking all of your senses into account. How does each area feel to you?

- Some general principles of environmental design include[271]:

- Give people choices. Let them control the temperature or the radio station or the TV station. Let staff give input into artwork, furniture, and the overall environment.

- Enhance human connection, while respecting privacy. Make waiting areas and other commons areas welcoming, while ensuring that staff knock on doors before entering.

- Keep sensory inputs healthy. Keep noise down (carpet, soundproofing walls, and keeping noise down in nearby rooms can help) and use cleaners and hand gels that do not smell overly “chemical.”

- Ensure people can find their way around easily. Maps and signs are part of a healing environment.

- Bring in art. Art exposure can reduce pain, improve clinical and behavioral outcomes, and boost staff morale. Art can be a helpful diversion—videos, fireplaces, and aquariums can also be useful.

- Pay attention to color as well. Remember that people in hospital beds and in examination rooms may spend time staring at the ceiling. Paint should not be overly reflective. People prefer soft tints of reds, blues, and greens with coral, colonial green, peach, rose, and pale gold being good options. Cooler colors are better for chronic patients and those who are likely to be under stress in places like a procedure waiting room.

- Make sure light exposure is good. Photon levels influence mood and wakefulness. People in hospitals and nursing homes have better sleep at night with good daytime light exposure. People who receive more sunlight need less pain medication and feel less stress.

- Sound also matters. Being startled by a noise can lead to changes in blood pressure and heart rate that last for hours. Noise can increase perceived pain and pain medication use. It may even lengthen hospital stay. Less noise correlates with less staff burnout. Varied and relaxing music can settle down heart and respiratory rates. Varying audio input seems to have more restful effects than total quiet.

- Enhance connection with nature. People recover better from stress when exposed to natural settings, and views outside can be helpful. Windows are preferable in hospital rooms. Incorporate plants and provide fresh air.

- Some clinicians appreciate bringing in principles of feng shui, which can be used to guide the design of a healing space.</;o>

Surroundings Resources

Websites

VA Whole Health and Related Sites

- A Patient Centered Approach To: Surroundings. Part of the Components of Health and Well-Being Video Series. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ge3tx1klZrc&feature=youtu.be

- Veterans Whole Health Education Handouts. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-handouts/index.asp

- An Introduction to Surroundings for Whole Health

- Assessing Your Surroundings

- Too Much Bad News: How to Do an Information Fast

- Toxins and Your Health

- Workaholism

- Improve Your Health by Removing Toxins From Your Body

- Ergonomics: Positioning Your Body for Whole Health

- National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. http://www.prevention.va.gov/

- Healthy Living Messages. http://www.prevention.va.gov/Healthy_Living/

- Veterans Experiencing Homelessness. http://www.va.gov/homeless

- VA National Center for PTSD: Types of Trauma. Includes military sexual trauma information. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/types/index.asp

- VA Public Health. Multiple resources, including a section, “Military Exposures.” http://www.publichealth.va.gov

Whole Health Library Website

- Surroundings. Overview. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/surroundings/

- The Healing Benefits of Humor and Laughter. https://www.wholehealth.wisc.edu/tool/healing-benefits-humor-laughter

- Animal-Assisted Therapies. https://www.wholehealth.wisc.edu/tool/animal-assisted-therapies

- A Media/Information Fast. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/tools/media-information-fast.asp

- Improving Work Surroundings Through Ergonomics. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/improving-work-surroundings-through-ergonomics

- Workaholism. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/workaholism

- Informing Healing Spaces Through Environmental Design: Thirteen Tips. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/healing-spaces-environmental-design

- Food Safety. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/food-safety

- Personal Health Plan Template. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/414/2018/08/Brief-Personal-Health-Plan-Template.pdf

- Whole Health for Skill Building: Surroundings. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses/whole-health-skill-building/

- Faculty Guide

- Veteran Handout

- Veteran Tool: “Thinking About Your Surroundings”

- PowerPoints

- Mindful Awareness Script: Mindful Awareness in Your “Special Place”

Other Websites

- Bright Light Therapy: A Non-Drug Way to Treat Depression and Sleep Problems. University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/files/webfm-uploads/documents/outreach/im/handout_light_therapy.pdf

- Detoxification diet information. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. http://www.eatright.org/resource/health/weight-loss/fad-diets/whats-the-deal-with-detox-diets

- Environmental Health and Medicine Education Resources for Health Professionals. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/emes/health_professionals/index.html

- Environmental Working Group. Has guides that focus on everything from pesticides in foods to green household cleaners and cosmetics. www.ewg.org.

- Sustainable Product Data. Source for guidance regarding healthy building materials and products. www.greenguard.org.

- International OCD Foundation Hoarding Fact Sheet. https://iocdf.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Hoarding-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- National Association of Professional Organizers. www.napo.net

- National Coalition for Homeless Veterans Helpline. http://www.NCHV.org

- National Library of Medicine Environmental Health. A well-done introduction to environmental health and links to key resources. Refer to the “Related Topics” list for air pollution, drinking water, molds, noise, and water pollution. https://medlineplus.gov/environmentalhealth.html

- Other web resources are listed at the end of the “Surroundings” overview featured in the Whole Health Library website section above.

- Poisoning, Toxicology, Environmental Health, National Library of Medicine. This site has user-friendly images that not only show the user potential sources of toxin exposure but also link to reliable government sources of additional information. https://medlineplus.gov/poisoningtoxicologyenvironmentalhealth.html.

- U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration Safety and Health Topics. Covers an array of different environmental toxins. www.osha.gov/SLTC/index.html.

Books

- Clutter’s Last Stand, Don Aslett (2005)

- Fast Media, Media Fast: How To Clear Your Mind and Invigorate Your Life, Thomas Cooper (2011)

- Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being, Esther Sternberg (2010)

- Home Enlightenment: Create a Nurturing, Healthy, and Toxin-Free Home, Annie Bond (2008)

- Home Safe Home: Creating a Healthy Home Environment, Debra Dadd (2005)

- Integrative Environmental Medicine, Aly Cohen (2017)

- Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder, Richard Louv (2008)

- Super Natural Home: Improve Your Health, Home, and Planet—One Room at a Time, Beth Greer (2009)

- The Not So Big Life: Making Room for What Really Matters, Sara Susanka (2007)