Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 7

Chapter 7. Personal Development: Personal Life & Work Life

Life isn’t about finding yourself. It is about creating yourself.

―George Bernard Shaw

The Many Facets of Personal Development

The Personal Development circle involves all the ways that you can grow as a person. It focuses on how you spend your time and energy during the day, and how you invest in what matters most to you. The possibilities seem almost endless for ways Veterans can choose to focus on Personal Development when they are creating their Personal Health Plans (PHPs). Working with Whole Health Partners and Coaches can certainly support Personal Development. What are some other possibilities?

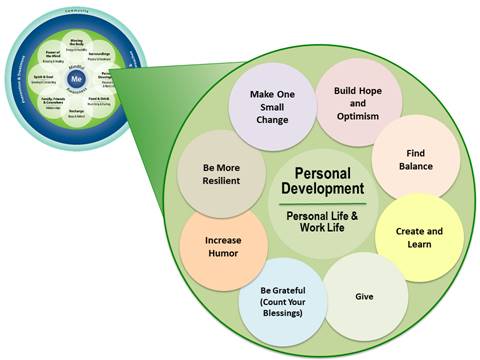

One option is to look at the “subtopics” related to the Personal Development self-care circle, as shown in Figure 7-1. The subtopics were created for the self-care skill-building courses for Veterans, introduced in Chapter 5. These subtopics encourage Veterans to think about options and focus in on which ones they want to use in their PHP. Note that there is a “Make One Small Change” circle that leaves room for creativity, if Veterans do not see an option that interests them.

This chapter will review 14 well-researched items, tied in with these circles, that can be considered when Personal Development is the focus[272]:

|

1. Improve the Quality of Your Work Life |

9. Balance (Integrate) Work and Other Areas of Life |

Questions to Ask About Personal Development

These are just a few of the questions you might consider when you discuss Personal Development during personal health planning:

- What do you do during the day?

- Describe a typical day (at home or at work or both).

- Do you work outside the home? Where do you work?

- What sort of work did you do before you retired?

- How is your relationship with your co-workers?

- How do you feel about the amount of time you work? Is work balanced well with other aspects of your life?

- Do you enjoy your work?

- Is your work fulfilling?

- To what extent are you defined by our job?

- Is your job an expression of who you are?

- Do you have the job you want? If not, what is your ideal job?

- What are your greatest strengths? What has enabled you to make it this far?

- What gives you the strength to take on life’s burdens?

- What would help you to handle life’s challenges better?

- Who are your role models?

- Are you happy? What makes you happy?

- Are you hopeful about the future?

- Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

- Are you kind to yourself?

- How many times a day do you laugh?

- What do you do well?

- What would you like to learn more about?

- Do you do any volunteer work?

- What are you most proud of?

- What is your greatest talent?

- What creative and artistic pursuits do you enjoy?

- Is there anyone you feel you need to forgive?

- What are you grateful for? What are your blessings?

Fourteen Key Elements of Personal Development

This chapter highlights key elements related to the Personal Development area of self-care. If you would like to cover these and more topics in greater detail, go to “Personal Development” on the Whole Health Library website.

Personal Development topics can easily be classified as belonging under other circles too. Social capital, for example, is covered in Chapter 10, “Family, Friends, & Co-Workers.” Leisure time and hobbies, including taking breaks and vacations, are covered in Chapter 9, “Recharge.”

1. Improve the Quality of Your Work Life

We know Quality of Work Life (QWL) is important in many professions. When doing personal health planning, it can be useful to ask about one step a person could take to improve the quality of their work life. A 1997 meta-analysis among nursing staff found that the following workplace characteristics favorably influenced QWL.[273]

- Autonomy. It is important to have some control over one’s work experiences.

- Low levels of stress. Chapter 12, “Power of the Mind” covers a number of options that might help with this.

- Good relations with supervisors.

- Low levels of role conflict. Everyone should be clear on their responsibilities.

- Appropriate feedback on performance. Good feedback is timely, constructive, and focused on personal and professional growth.

- Opportunities for advancement. What is a person’s long-term trajectory at work?

- Fair pay. Is a person receiving a salary comparable to others doing the same work?

Regardless of what sort of work a person does, discussing these factors might be helpful. In nursing, they are known to be linked to lower burnout rates, better working environments, and fewer injuries on the job. They are tied to better patient outcomes as well.[274] For some, “work life” might include working at home, doing volunteer work, or doing childcare.

Burnout

For all people in the helping professions, burnout is a high risk. For example, in Medscape’s January 2020 Lifestyle Report, based on a survey of over 15,000 physicians from 29 different specialties, the number of physicians reporting being burnt out ranged from 29-54%, depending on specialty.[275] Rates were higher in women and in people from Generation X versus baby boomers or millennials. In addition, as many as 60% of psychologists also struggle with burnout.[276] A 2005 study of 751 practicing social workers found a current burnout rate of 39% and a lifetime rate of 75%.[277] In a survey of 257 RN’s, 63% reported burnout.[278] In a 2018 meta-analysis of 21 studies focused on nurses, rates of compassion fatigue and burnout were 53% and 52%.[279]

For health care workers, burnout occurs in part because of poor QWL due to excess bureaucratic challenges and long hours (these were the main causes noted in the Medscape Survey)4 as well as workload, loss of autonomy, administrative burdens, and challenges balancing work demands with other aspects of life.[280] Perfectionism, lack of stress-coping skills, unhealthy personal habits (such as substance use disorder), poor relationships with colleagues, poor self-care, and difficult patients can also contribute.[281],[282] Burnout also affects teachers, lawyers, mental health professionals, social workers, and many other groups. It has three main aspects:

- Emotional exhaustion

- Cynicism and depersonalization

- A sense of low personal accomplishment

Many burnout questionnaires are used in the research, but burnout can quickly be assessed using two questions. They are worth asking routinely and include[283]:

- Do you feel burned out or emotionally depleted by your work?

- Have you become more callous toward people since taking this job—treating patients and colleagues as objects instead of people?

Burnout has been found to improve with various interventions, including mindfulness training. In 2009, Krasner and colleagues3 evaluated how a course on mindful communication, offered to a group of 70 primary care physicians, improved all 3 aspects of burnout.[284] A University of Wisconsin group conducted a pilot study that provided abbreviated, tailored mindfulness training (18 hours) to 30 primary care clinicians.[285] Data at nine months post-intervention showed statistically significant improvements in measures of job burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress. Another study of 93 different types of health care clinicians, including nurses, social workers, and psychologists, also found that all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory improved for participants after they took an eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course.[286]

Burnout can be reduced if a person has greater individual autonomy, a stronger sense of balance between work and other obligations, strong relationships with colleagues, and a sense of shared values at work. It helps if support for burnout reduction is offered at an institutional level.[287] It is NEVER helpful to place the blame for burnout on the person who is experiencing it. Some employers and institutions mistakenly do so. Do not blame the victim.

One simple method for decreasing burnout is the following exercise. Have Veterans give it a try and try it yourself.

|

End of the Day Exercise At the end of each day, on the way home from work, after dinner, or before you go to bed, ask yourself the following three questions:

Anything to reduce burnout is a positive step in the direction of Whole Health. Burnout is the “shadow side” of resilience, which is another fundamental aspect of personal development, for patients and clinicians alike. [288] |

2. Foster Resilience

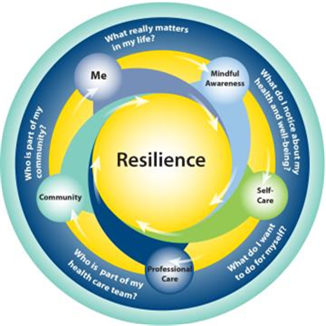

Resilience involves being able to adapt to changing environments, identify opportunities, adapt to constraints, and bounce back from misfortunes and challenges.[289] Figure 7-2 is the Circle of Resilience, which explores how the Circle of Health might relate to fostering resilience.

Anything that can foster resilience can be an invaluable part of a PHP. How do we foster resilience? Cultivating positive emotions can help with our adaptability in the face of change or disruption. It has been noted that resilient people have negative emotions just as much as other people, but they generate many more positive emotions compared to those who are less resilient.18 Increased attention is being paid to Veterans’ experiences with post-traumatic growth, which includes the positive psychological changes that can occur after trauma.[290] The neurobiology of resilience is also garnering increased attention.[291],[292]

The following are tips for increasing resilience in three different areas. They can be used by patients and clinicians alike. Many tie in with other parts of the Circle of Health as well.1

1. Attitudes and Perspectives

- Find a sense of meaning related to the work you do.

- Foster a sense of contribution.

- Stay interested in your roles.

- Accept professional demands.

- Come to terms with personal concerns (self-acceptance) and confront perfectionism.

- Work with thinking patterns.

- Develop a health philosophy for dealing with suffering and death.

- Exercise self-compassion.

- Give up the notion that you have to figure everything out.

- Practice mindful awareness.

- Interject creativity into work; consider an array of different therapeutic options, as appropriate.

- Treat everyone you see as though they were sent to teach you something important.

- Identify what energizes you and what drains you, seeking out the former.

2. Balance and Priorities

- Be aware of both personal and work goals.

- Balance work life and other aspects of life effectively.

- Set appropriate limits.

- Maintain professional development.

- Honor yourself.

- Exercise.

- Find time for recreation.

- Take regular vacations.

- Engage in community activities.

- Experience the arts.

- Cultivate a spiritual practice.

- Budget your time just as you might your finances, planning ahead when possible.

3. Supportive Relations

- Seek and offer peer support.

- Network with peers.

- Find a supportive mentor or role model.

- See your primary care provider.

- Consider having your own psychologist or counselor.

- Nurture healthy family, friend, and partner relationships.

3. Increase Happiness

An important question to ask when using the Whole Health approach is simply, “Are you happy?” Fostering happiness has, as you would expect, numerous benefits.[293] There are three main aspects of happiness that are described in psychology research.1

- The pleasant life (positive emotions and pleasure).

- The engaged life (pursuing work, relationships, and leisure).

- The meaningful life (life has meaning, and one serves something one believes is bigger than oneself). This ties into the question of “what really matters.” It can also tie into someone’s spirituality, as discussed in Chapter 11.

People who pursue all three aspects are the most satisfied,[294] and the meaningful life has the most impact. Happier people are more successful, more socially engaged, and healthier.[295] People are happiest if they can identify and use their signature strengths.[296] Studies show that happiness is linked to positive outcomes such as financial success, supportive relationships, mental health, effective coping, physical health, and longevity.18 It is important to remind people that the pursuit of happiness can be misdirected; people who equate money with happiness, for example, may end up less happy.[297] Ideally, happiness is one of an entire spectrum of healthy emotions people experience, when appropriate.

4. Cultivate Hope and Optimism

The definition of hope involves three components. These include the following:

- Having goals related to a situation.

- Believing one has the ability to reach those goals. Sensing one can know the path to follow in order to achieve goals in any situation.

Hope is linked to a stronger sense that life is meaningful,[298] as well as to more positive emotions and productivity at work. Optimism is a more general term, based around the idea that positive things will happen in the future.

Optimism has been linked to taking more proactive steps for one’s health, more effective coping, better physical health, and better socioeconomic status. It also seems to be associated with persistence with educational pursuits, better income, and stronger relationships.[299] It is associated with decreased pain sensitivity and better adjustment to chronic pain as well.[300] A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis found that optimism is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.[301] With practice, people can learn to be more optimistic. Mind-body skills training can be helpful in cultivating optimism, as noted in Chapter 12, “Power of the Mind.”

5. Develop Self-Compassion

Self-compassion involves directing care, kindness, and compassion toward oneself. It includes the realization that all experiences we have are part of the common experience of all people. Understanding that can help us be gentler with ourselves.

Mindful awareness is closely linked to self-compassion. One of the mindful awareness practices featured in Chapter 10 is the loving-kindness meditation. This practice begins by wishing oneself well. After that, you extend the compassion out to others. The practice also concludes with a moment of self-compassion. It is not uncommon for compassion-based meditations to begin with focusing on self-compassion as the beginning and ending points of cultivating compassion for others.

Research indicates that having more self-compassion is linked to optimism and happiness, as well as to more successful romantic relationships and overall well-being.[302],[303] Having more self-compassion is linked to greater levels of resilience.[304] A 2011 meta-analysis of 20 different studies found a large effect size when self-compassion was used to treat stress, anxiety, and depression.[305] It may reduce the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and self-harm as well.[306] Self-compassion was linked to having more happiness, optimism, curiosity, wisdom, exploration, and emotional intelligence, in addition to other qualities.34 It is also linked to better self-care and lower levels of negative affect.[307],[308] It is linked to well-being outcomes in older adults.[309] A 2020 systematic review concluded that focusing on and using one’s strengths improved psychological well-being in people with chronic illness.[310]

6. Commit Random Acts of Kindness

Random acts of kindness involve doing something for an unknown person that you hope will benefit them.[311] Examples might include paying for the order of the person behind you at the drive through restaurant or putting money in someone’s expired parking meter. You can offer a stranger a flower, or write a kind note to someone about something you appreciate. These acts are linked to greater life satisfaction[312] and greater happiness.24 Functional MRI studies indicate that imagining kindness activates the emotional regulation system of the brain. Kindness can become a self-reinforcing habit that becomes easier over time as neural connections build in a positive way.[313] Encourage Veterans to give them a try. It can help to strategize in advance about what those acts could be.

7. Enhance Humor and Laughter

In the 1970s, word spread that journalist Norman Cousins had improved his symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis through the use of humor.[314] Laughter affects us in many positive ways.[315] Laughter increases our pulse, breathing rates, and oxygen use, and it decreases blood vessel resistance, all of which can be beneficial. After we laugh, we feel more relaxed. 10-15 minutes of laughter daily can burn 10-40 extra calories. Intense laughter relaxes muscle tone. Humor seems to calm down the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the ‘fight or flight’ response. It lowers stress hormone levels. It also bumps up endorphins (the feel-good chemicals in the body) and helps immune system function.

In terms of specific illnesses, laughter44:

- Decreases anxiety

- Lowers heart attack risk in high-risk diabetics

- Increases good cholesterol (HDL)

- Is linked to lower coronary heart disease and reduced arrhythmias and recurrent heart attacks for people in cardiac rehabilitation

- Increases pain tolerance and decreases body inflammation

- Relaxes the airways

- Reduces allergic reactions

The great thing about laughter is that there are many ways to make it happen. Be sure to mention it to patients, so they know it ‘counts’ as something they can do for their Whole Health. Build up your own repository of jokes to use with patients, as appropriate. For some more ideas, including about how to do Laughter Yoga, refer to the Resources at the end of this chapter. Laughter Yoga research is in its early stages, but it is known to improve depression in life satisfaction in elderly women.[316] It also increases heart rate variability, which corresponds to better overall health.[317] It also shows promise for improving depressive symptoms (weak evidence).[318]

8. Build Creativity

Creativity can be defined as the generation of something new, different, novel; it may also involve taking something already known and elaborating on its uses, characteristics, or evolution. It can refer to a process (the “creative process”) or to the product that is generated from the process.1 Creativity has many domains, or aspects; attitudes, skills, knowledge, motivations, and personality traits are all factors that lead to creative thinking and behavior.[319] It can be helpful to explore what creative pursuits someone enjoys, because that can help guide personal health planning recommendations. Many creative activities can help a person relax, not to mention engage them socially. The benefits of creative arts therapies are discussed in Chapter 12.

In terms of research related to creativity, we know that it is enhanced by supportive environments, having control over aspects of your life, and internal motivation.[320] We know that it can engage problem solving as well as the generation of new ideas.49 Creativity can be promoted through meditation.[321] Studies on the health benefits of creativity are still needed. Research suggests that creativity can be enhanced if you keep a verbal or written record of ideas, put yourself in novel and interesting circumstances, learn something outside your area of expertise, seek out challenging tasks, or “sleep on” tough problems.[322]

Encourage people to consider all the different ways they could potentially make use of their creativity. Examples range from writing or making art to building something, doing improv, solving puzzles, or doing various crafts.

9. Balance (Integrate) Work and Other Areas of Life

Most of the literature on this topic can be searched using the term “Work-Life Balance.” However, this term implies that work is not a part of “life,” or perhaps that work has to be time spent doing something negative, which is not true for many people. As Swiss philosopher Alain de Botton put it, “There is no such thing as work-life balance. Everything worth fighting for unbalances your life.”[323] Recently, people have begun to use the term, “work-life integration.” Recently, it has also been referred to as “work-life blend,” given that it is now possible with technology to take work with us wherever we go. However you describe it, the balance between work and other aspects of life is[324]:

- An important contributor to satisfaction and well-being for clinicians, and for everyone trying to find it; without it, quality of life and overall life satisfaction are adversely affected.[325]

- Made up of three types of balance, and all of them are important:

- Time balance—how much time is devoted to different activities.

- Satisfaction balance—how much satisfaction different parts of your life give you.

- Involvement balance—how much you engage in various responsibilities. It is not merely about balancing time; it is about being committed and present during all the aspects of your life.

- Something you can enhance, using the following tips53,[326]:

- Allow for spontaneity. This is not something you just plan; it is like walking across a stream on slippery rocks. You have to keep reassessing and changing course.

- Ensure that every day you accomplish something. AND every day you find joy or fun. AND every day you connect with another person in a positive way. Ask yourself from time to time if your work feels meaningful.

- Do not be trapped by delayed gratification. Allow yourself to experience positive aspects of life regularly.

- Check in with others for a perspective on how balanced you are. You may be enduring more than you realize or working harder than you think.

- Share experiences with others—friends, loved ones, and colleagues.

- Advocate for institutional changes at work if there are threats to employees’ balance.

For more information, go to the Whole Health tools, “Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources” and “Workaholism.”

10. Explore Lifelong Learning

Research shows education is a powerful influence on health and well-being. It is linked to midlife cognitive abilities (how well you think as you age),[327] as well as longer telomere length.[328] Telomeres are areas on the ends of chromosomes; the longer they are, the lower a person’s risk of chronic disease and death. More education corresponds with lower risk of mortality.[329] Higher education is one of the most effective ways to raise family income.[330] Education seems to decrease stress and slow aging, too.[331] Lifelong learning keeps us up to date in an era when technology and research are constantly advancing. It can involve taking courses, completing a GED or degree program, working with vocational rehabilitation experts, or deciding how often to read up on new discoveries and innovations.

Lifelong learning can also involve cultivating various life skills. Research indicates life skills are important to health. For example, a 2017 study of over 8,100 men and women over age 52 found that having five key life skills—conscientiousness, emotional stability, determination, control, and optimism—was favorably linked to wealth, income, mood, social connection, incidence of a number of chronic diseases, activities of daily living, walking speed, obesity, and self-rated health and well-being.[332] Even lab results, like HDL cholesterol, vitamin D, and C-reactive protein were significantly better. No one skill was responsible; it was having a combination of various skills that made the most difference.

A lifelong learner [333]:

- Is flexible

- Reflects on what has been learned

- Is aware of the need for lifelong learning

- Requests feedback

- Is able to share what has been learned

- Is highly motivated

- Clearly sees how to use what has been learned and apply it in daily life

- Is aware of resources that can help with making future improvements

Encourage Veterans to think about learning and how they would like to do it. Frame it in terms of work and financial well-being as well. Vocational rehabilitation can be a great resource in many VA facilities.[334],[335]

11. Volunteer

In 2019, 77.4 million Americans—over 30% of the population—volunteered over 6.9 billion hours of their time for organizations, with an estimated economic value of $167 billion.[336] Over 50% of people reported doing favors for their neighbors, and 43% noted they supported friends and family in some way. The strong presence of volunteer programs in VA programs is not only health-promoting for the recipients of the volunteers’ efforts, but also for the volunteers themselves. Volunteering[337],[338],[339],[340],[341],[342]:

- Increases longevity

- Improves functional ability

- Lowers rates of depression in the elderly

- Decreases heart disease incidence

- Improves mental health and life satisfaction, as well as quality of life

- Increases a sense of personal accomplishment

- Enhances social connections

- Increases well-being for people with chronic illnesses compared to medical care alone

- Protects against cognitive aging (keeps the brain working well)

- Leads to a “helper’s high” in elderly women volunteers. Some also reported they felt stronger, calmer, and had fewer aches and pains.

Veterans tend to enjoy working with other Veterans. Encourage them to volunteer. If you do so, it can be helpful to be able to provide them with a list of options.

12. Improve Financial Health

Financial health refers to the state of a person’s financial life or situation. It can include the amount of savings people have, how much they spend on fixed expenses like mortgage or rent, or their ability to stay out of debt.1 Financial literacy, the ability to make informed judgments and manage money, is also important.[343]

What do we know about money and health?1

- There is a small but positive link between income and happiness, but that decreases at higher income levels.

- Finances are a significant source of stress for 76% of Americans. Mindful awareness can help to reduce this stress. If people can identify stressors and make a plan, this can prove helpful.

- A financial planner can help as well.

- Enrolling in a course to build financial skills may be useful. Additional resources for fostering financial health are available in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

13. Practice Forgiveness

This is best framed as a Whole Health tool, which is located on the following page.

14. Practice Gratitude

This is also best framed as a Whole Health tool and is featured right after the Forgiveness tool.

Whole Health Tool: Forgiveness

Whole Health Tool: Forgiveness

What Is Forgiveness?

Forgiveness is a “…freely made choice to give up revenge, resentment, or harsh judgments toward a person who caused a hurt and to strive to respond with generosity, compassion, and kindness toward that person.”[344] When used therapeutically, forgiveness is a process—a series of steps to follow. It is not just an isolated event.

Forgiveness may also involve the need to forgive ourselves or to request forgiveness from another person for something we have done. It may also involve accepting a request for forgiveness.

The following are important points to keep in mind about forgiveness1:

- Forgiveness does not require us to reconcile with the offender and have continued contact. There are times when it is in our best interest to stay away from the offender.

- Forgiveness is a process that can take time; it is not just a decision we make quickly. To forgive generally requires some emotional and mental energy on our part.

- To forgive means that we have to fully accept what actually happened, how we were hurt, how our lives were affected by the offense, and even how we have changed as a result.

- When we do not forgive, we continue to give the negative experiences and the offender power over us. To forgive is to become free to move forward.

- We need never forget what happened; forgiveness does not have to involve forgetting. Despite our continued memory of the event, we nevertheless forgive and live life in the present.

- Forgiveness does not relieve offenders of their responsibility. If it is necessary to pursue justice, we can still take the action that is needed, such as pressing charges, filing complaints, or otherwise appropriately addressing concerns.

How Forgiveness Works

Forgiveness reduces repetitive thoughts (ruminations) that may be begrudging, vengeful, or fearful. It does NOT condone the behavior or event that caused harm, but rather, it frees the victim of that harm from continuing to suffer after the fact. It has been said that forgiveness is “…giving up all hope of a better past.”

How to Use It

There are a number of forgiveness materials and books available to help people move through the forgiveness process. However, people should know that this process could trigger emotions and memories, so it may be helpful to work through with a licensed mental health professional, if needed.

The forgiveness process tends to move through stages.[345] These include the following:

- Recognize the need to forgive. Learn how an offense has affected us and how it has continued to preoccupy us.

- Acknowledge and release emotions.

- Decide to forgive. Making the decision to forgive is an important step.

- Change old beliefs and patterns. Gain a deeper understanding and try to experience more empathy and compassion for ourselves and the perpetrator.

- Emerge into greater wholeness. Find meaning in the suffering, and recognize suffering is universal.

When to Use Forgiveness

Forgiveness can be used whenever a person needs to work with traumatic past experiences. A 2019 meta-analysis found 128 studies including a total of more than 58,500 people that showed a positive relationship between forgiveness of others and physical health.[346] Currently, research shows that it is associated with the following[347]:

- Improved mental health, as well as reduced negative affect and emotions

- Satisfaction with life and, potentially, better psychological health[348]

- Fewer physical ailments and somatic complaints, as well as less medication use

- Reduced fatigue and better sleep quality

- Reduced depression, anxiety, and anger

- Reduced risk of myocardial ischemia and better cholesterol numbers in patients with coronary artery disease

- Decreased vulnerability to chronic pain

- For people with substance use disorders, a lower likelihood of using illicit drugs

- Better work life, if one practices forgiveness with co-workers; productivity, mental health, and physical health improve[349]

- A weakened relationship between negative experiences and self-harm (according to self-forgiveness research)35

- Better cognitive function (with self-forgiveness and decreasing one’s hostility)[350]

Forgiveness is not a process that can be done in a hurry. It requires time for reflection and, often, time to work with a clinician or coach to move through the emotions and other challenges that come up as one moves through the process. A person should never be rushed through the stages of forgiveness.

Tips from Your Whole Health Colleagues

- If you are going to recommend forgiveness to people you see in your practice, become as familiar as you can with the Resources at the end of this chapter.

- This process cannot be rushed. And, it is completely worth the time investment.

- Self-forgiveness is also important to explore.[351] It is linked to decreased risks of suicidal ideation and self harm.35

- Use the Resources at the end of this chapter to take the process deeper, and if interested, refer to the Whole Health tool, “Forgiveness: The Gift We Give Ourselves.”

Whole Health Tool: Gratitude

What Is Gratitude?

Gratitude is a strong contributor to happiness and well-being. Found across all cultures, gratitude is universal. It shares origins with the word “gratia,” which means grace. It is both an attitude and a practice. It is closely linked to thankfulness and appreciation.

How Gratitude Works

Gratitude practice is a direct cause of well-being, and it also protects against negative emotions and mental states. Some of its benefits include the following[352],[353],[354]:

- Self-reported physical health

- Increased happiness, pride, and hope

- Enhanced social connection and decreased loneliness

- Reduced risk for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation

- Improved body image

- Higher likelihood of performing acts of kindness, generosity, and cooperation

- Resilience and more robust physical health

- Better sleep and energy level

Gratitude influences our neural networks, including how the brain and heart connect with one another; this is revealed in studies that look for links between heart rate and activation of different parts of the brain on functional MRI.[355] Keeping a gratitude journal leads to more regular exercise, greater optimism, and more alertness, enthusiasm, determination, attentiveness, and energy. People also become more supportive of other people.[356] Study participants who wrote about three good things that happened each day and why they happened felt happier and less depressed even six months later.25

Gratitude from patients to their care teams also has benefits. In a study of neonatal ICUs, medical teams performed better when patients expressed gratitude for their care.[357]

How to Use It

There are different ways to cultivate gratitude, and the following are just a few examples of exercises you can suggest.25

Grateful Contemplation Exercise 1: Happy Moment Reflection. Reflect on a happy moment that stays strong in your memory even though it may have happened years ago. Relive it, using all your senses. What about the experience stays with you? Was gratitude part of it? Write down your reflections.

Grateful Contemplation Exercise 2: Gratitude Attitude. Practice having an attitude of gratitude throughout the day. Think of cues you can use to remind you to be grateful. Examples might be a phone alarm, starting your commute home, sitting down to a meal (many people “say grace” before meals), or passing through the doorway to a building or room. Acknowledge—and enjoy—the positive things that happened during your day.

Grateful Contemplation Exercise 3: A Written Gratitude Practice. Find a regular time at the end of the day to reflect on the day and write down five things you are grateful for. Take time to reflect on their value as you write them. Writing them down is more powerful than just thinking about them. Use a special journal or write what you are grateful on a piece of paper and put it into a jar. Consider listing simple everyday things, people in your life, personal strengths or talents, moments of natural beauty, and/or gestures of kindness from others. Review the list (or open the jar) every so often, perhaps monthly or yearly, as a reminder.

Grateful Contemplation Exercise 4: Gratitude Visits.25 Write and deliver a letter of gratitude to someone who has been very kind to you but whom you have never properly thanked. This practice has been found to lead to increased happiness and reduced depression for the person writing the letter (and it helps the recipient too).

When to Use Gratitude

Gratitude practice can be used by anyone. It may be particularly useful for those who do not routinely feel grateful or struggle with low mood or depression.

What to Watch Out for (Harms)

Gratitude practices tend to be quite safe.

Tips from Your Whole Health Colleagues

The following tips are from the Whole Health tool “Creating a Gratitude Practice”:

- If you find your gratitude practice is getting stale, mix it up a bit; switch to another format to make it work for you.

- Pick one co-worker each day, and express thanks for what he or she is doing for the organization.

- Take turns going around the dinner table and share one thing each person is grateful for that happened that day.

- Express appreciation about what your partner, child, or friend does and who they are as a person.

- Go for a walk with a friend and talk about what you are most grateful for.

- Do an art project that focuses on your blessings and what is going well in your life.

- Write a thank you letter to yourself.

- Give thanks for your body.

- Pause to experience wonder about some of the ordinary moments of your life.

- Imagine your life without the good things in it, so as not to take them for granted.

Personal Development Resources

Websites

VA Whole Health and Related Sites

- A Patient Centered Approach To: Personal Development. Part of the Components of Health and Well-Being Video Series. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYZfEA5RgNw&feature=youtu.be

- Veterans Whole Health Education Handouts. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-handouts/index.asp

- An Introduction to Personal Development

- Finding Balance

- The Healing Power of Hope and Optimism

- Create a Gratitude Practice

- Forgiveness

- What Matters Most? Exploring Your Values

- Laughter Heals

Whole Health Library Website

- Personal Development. Overview includes an extensive list of financial health resources. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/personal-development

- Values. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/values

- Creating a Gratitude Practice. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/creating-gratitude-practice

- Forgiveness: The Gift We Give Ourselves. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/forgiveness-the-gift-we-give-ourselves/

- The Healing Benefits of Humor and Laughter. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/healing-benefits-humor-laughter

- Taking Breaks: When to Start Moving, and When to Stop. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/taking-breaks-when-to-start-moving-and-when-to-stop/

- Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/work-life-integration-tips-and-resources/

- Workaholism. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/workaholism/

- Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care. Overview. Focuses on clinicians’ Personal Development (and Self-Care). https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/clinician-self-care/

- Self-Management of Chronic Pain. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/self-management-chronic-pain

- Personal Health Plan Template. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/414/2018/08/Brief-Personal-Health-Plan-Template.pdf

- Whole Health for Skill Building: Personal Development. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses/whole-health-skill-building

- Faculty Guide

- Veteran Handout

- PowerPoints

- Mindful Awareness Script: A Mindful Awareness Experience to “Get Your Gratitude On”

Other Websites

- Laughter Yoga International. https://laughteryoga.org/

- Money Management International. Nonprofit agency that provides free education about credit and debt management. https://www.moneymanagement.org/

- Money Smart. FDIC education program with online financial training materials. https://moneysmartcbi.fdic.gov

- Self-Compassion. Includes practices and other resources. http://self-compassion.org

- Forgiveness Resources

- Fetzer Institute. https://fetzer.org/

- Forgive for Good. http://learningtoforgive.com/

- International Forgiveness Institute. https://internationalforgiveness.com/

- The Forgiveness Project. https://www.theforgivenessproject.com/

- World Forgiveness Alliance. http://www.forgivenessday.org/

Books

- 21 Keys to Work/Life Balance: Unlock Your Full Potential, Michael Sunnarborg (2013)

- A Life at Work: The Joy of Discovering What Your Were Born to Do, Thomas Moore (2009)

- Encore: Finding Work that Matters in the Second Half of Life, Marc Freedman (2008)

- Enjoy Every Sandwich: Living Each Day as If It Were Your Last, Lee Lipsenthal (2011) (Dr. Lipsenthal wrote this book shortly before his death from colon cancer.)

- Finding Balance in a Medical Life, Lee Lipsenthal (2007)

- Forgive for Good: A Proven Prescription for Health and Happiness, Fred Luskin (2002)

- Forgiveness Is a Choice: A Step by Step Process for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope, Robert Enright (2001)

- Forgiveness: A Bold Choice for a Peaceful Heart, Robin Casarjian (1992)

- Forgiveness: The Greatest Healer of All, Neale Walsch (1999)

- Life Is Not Work, Work Is Not Life: Simple Reminders for Finding Balance in a 24-7 World, Walker Smith (2001)

- No Regrets: A Ten-Step Program for Living in the Present and Leaving the Past Behind, Hamilton Beazley (2004)

- Off Balance: Getting Beyond the Work-Life Balance Myth to Personal and Professional Satisfaction, Matthew Kelly (2011)

- Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges, Steven Southwick (2012)

- Stop Living Your Job, Start Living Your Life: 85 Simple Strategies to Achieve Work/Life Balance, Andrea Molloy (2005)

- Striking a Balance: Work, Family, Life, Robert Drago (2007)

- The Book of Forgiving: The Fourfold Path for Healing Ourselves and Our World, Desmond Tutu (2015)

- The Forgiving Life: A Pathway to Overcoming Resentment and Creating a Legacy of Love, Robert Enright (2012)

- The Medical Marriage: Sustaining Healthy Relationships for Physicians and Their Families, Wayne Sotile (2000)

- Zen and the Art of Making a Living: A Practical Guide to Creative Career Design, Laurence Boldt (2009)

Special thanks to Shilagh Mirgain, PhD, and Janice Singles, PsyD, who wrote the original Whole Health Library materials on Personal Development that inspired content for much of this chapter.

References