Family, Friends, and Co-Workers

In Whole Health, an essential aspect of creating a Personal Health Plan (PHP) is to focus on what really matters. Equally important is to ask a person, “Who really matters?” Family, Friends, & Co-Workers is the area of self-care from the Circle of Health that raises this important question. This overview, which builds on the materials featured in Chapter 10 of the Passport to Whole Health, reviews research related to relationships and health and highlights some ways that Veterans can focus on this essential aspect of well-being.

Key Points

- While focusing on relationships may feel intimidating to some, it is vitally important. Decreased loneliness correlates with increased health, and people do better with many health problems if they have people who can support them.

- Unfortunately, the average number of people a person is connected to has been decreasing in recent decades.

- There are many forms of social support, such as financial support, mentoring, and emotional support. All of them are important.

- Relationships affect us at the level of our physiology, as studies linking relationships and mirror neuron activity, oxytocin levels, and inflammatory markers have shown.

- Therapeutic relationships between clinicians and patient have a significant impact on outcomes.

- Examples of ways to enhance connections include practicing compassion, getting support from social workers, volunteering, joining support groups, and becoming more involved in one’s community.

Meet the Veteran: Michael

Replace ‘I’ with ‘We’ and illness becomes wellness.

— Swami Satchidananda

Michael is a 70-year-old former Marine Corps Sergeant who served in the Vietnam War. He was adopted and did not have strong relationships with his adoptive parents. He chose to enlist in the Marines right out of high school in 1966 and served through 1972. In the course of his service, many of his friends were killed or sustained injuries, especially during the Tet Offensive in 1968. Being a Marine and having a connection to his fellow Marines gave him a sense of community and family that he had never known before in his life. It was hard for him to return home, knowing that he survived, and many others did not.

When he got home to Dayton, Ohio, he married his high school sweetheart, and they had a daughter within a year. He felt a strong sense of responsibility for his new family and focused on being a good provider. He worked as a mechanic for 12 years before getting a diploma in Business Management at his community college in his hometown. He retired from a management position at a car dealership in 2001. His daughter is now in her late 30s. She is married with two children and lives in California.

Michael recently had a heart attack and is going through the hospital’s cardiac rehabilitation program for the next 12 weeks. While recovering in the hospital, he started to reflect on his life more, and he noticed that he has felt disconnected from his family and life since he retired. He has been guarded with others ever since he came back from the war. He has never spoken to a mental health professional about the experiences and losses he has undergone throughout his life.

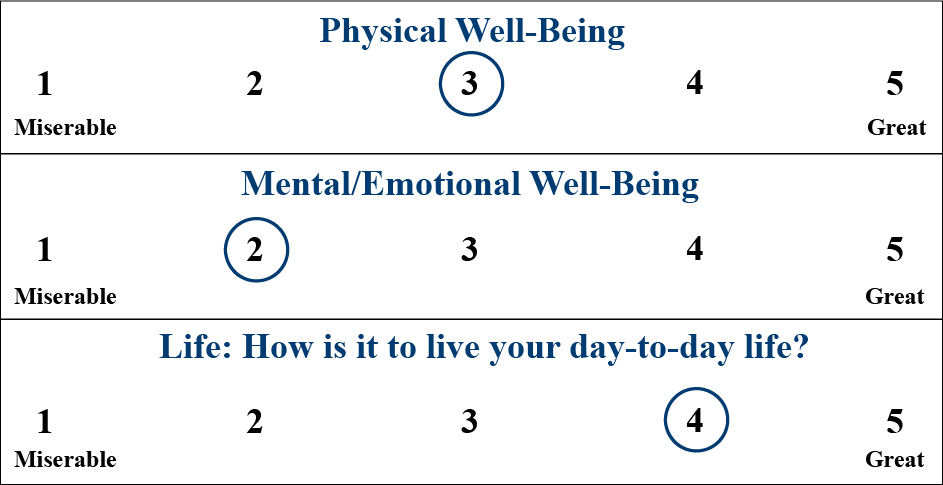

During his intake for the cardiac rehabilitation program, he was asked to complete a Personal Health Inventory (PHI) prior to his visit. A cardiac nurse practitioner reviewed it. His vitality signs varied a bit, and he said he rated himself lower on physical because of his heart attack. He gave himself a 2 on mental well-being because he is “so antisocial”:

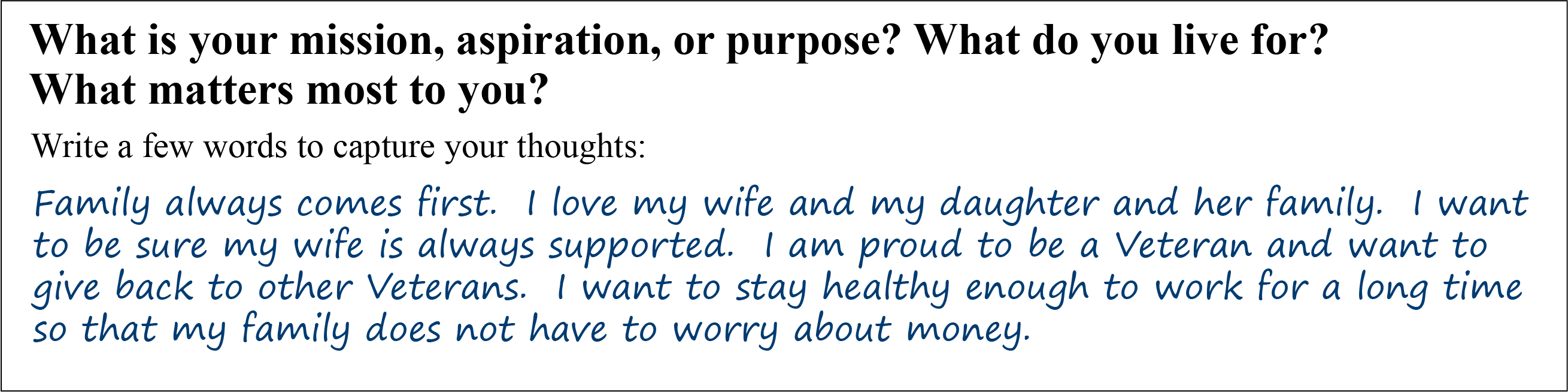

His answer to the second question gave the nurse practitioner a good sense of what was on his mind:

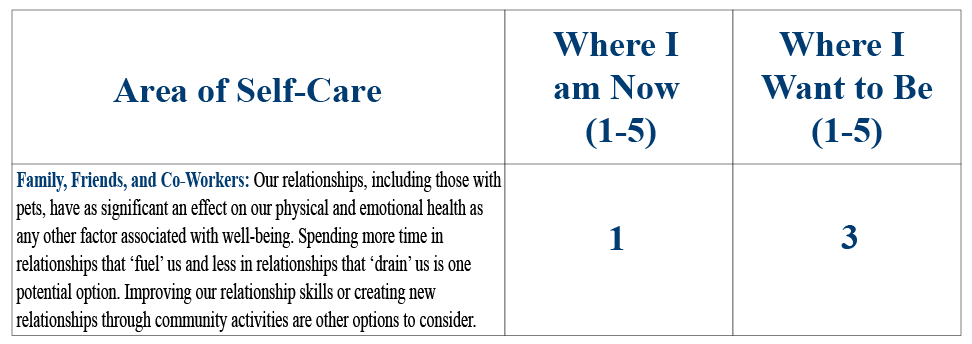

When asked about focusing on an area of self-care, there was no question for Michael that he wanted to start with Family, Friends, & Co-Workers. He gave himself a 3 on where he wants to be, he said, because “I just can’t believe that a guy like me could get over his emotional issues enough to ever go any higher.”

For the last two questions, he was not quite so free with his answers. Later, he says he felt a little uncomfortable with being asked:

Relationships and Health

In the Whole Health Skill-Building Courses for Veterans, the diagram shown in Figure 1 is used to give Veterans a framework for thinking about Family, Friends, & Co-Workers and incorporating that aspect of self-care into their Personal Health Plan (PHPs). Various “subtopic” circles are featured, and each of them can offer ideas for how to bring one’s relationships more fully into focus. Each of these areas is discussed in this overview.

Figure 1. Examples of Topics Related to Family, Friends, & Co-Workers

In 2014, researchers summarized findings from 23 interviews of Veterans with serious mental illness who had attempted suicide.[1] What did they describe as the main feelings preceding their suicide attempts? In addition to depression and hopelessness, they described that feelings of loneliness and isolation played a significant role. When asked what could be done to help Veterans like them to be at lower risk of committing suicide, they emphasized two key changes that they felt would be most helpful:

- VA clinicians should work to increase their empathy, compassion, and listening skills.

- More efforts should be made to bolster Veteran social support.

The purpose of this overview is to review key research regarding connections and health and to explore what clinicians can do to help Veterans relate better to family, friends, co-workers, and the members of their health care teams as they tune in to this important aspect of self-care. Of course, we know from firsthand experience that connection matters; it is really no surprise that research confirms that positive relationships decrease morbidity and mortality. The Harvard Women’s Health Watch summarized it nicely, reporting that, “People with satisfying relationships have been shown to be happier, have fewer health problems, and live longer. In contrast, having few social ties is associated with depression, cognitive decline, and premature death.”[2] Some of the specific studies leading to this conclusion will be discussed below.

Some definitions

Social support has three dimensions.

- Source of support. Where is the support coming from (family, friends, or programs in the community)?

- Satisfaction with support. It is important to consider how satisfied a person is with a given source of support. Not all social contact, as has been noted in the research, is actually supportive. Some relationships can lead to negative health outcomes. It is important to keep in mind that social support is in the eye of the recipient; if individuals are not satisfied with a source of support, they are not likely to receive health benefits.

- Type of support. Social support comes in a variety of types:[3]

-

- Emotional support—the person receives empathy, caring, love, trust, concern, and listening.

- Instrumental support—a person benefits from help in the form of time, labor, money, and direct help.

- Appraisal support—a person gets affirmation, evaluation, and feedback.

- Informational support—a person receives advice, guidance, suggestions, and information that can help her/him cope.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Your Social Support

Take a moment to consider your sources of social support, referring to the four types of social support listed above.

- Who are the 10 people in your life who matter the most to you? Who are you closest to in your family? Who is your best friend? Who is your most trusted colleague?

- Who provides you with emotional support?

- Who gives you instrumental support in the form of time, money, and other types of help?

- What about your sources of appraisal support? Who gives you affirmation, evaluation, and feedback?

- Where do you get informational support? Who offers you advice, guidance, and helpful suggestions?

- Who receives support from you? Which types of support—instrumental, appraisal, informational, emotional—do you offer them?

- How can you strengthen the supportive relationships in your life?

Relationships are Changing and Evolving with Our Culture

A relationship may be defined as “the way in which two or more people…talk to, behave toward, or deal with each other.”[4] In reviewing the research below, keep in mind that, especially in modern times, there are a vast number of possible relationships that Veterans can have. People may be much more connected to their “family of choice” than they are to their “family of origin.” Life partnerships can take many forms. The Internet and other forms of technology have led to multiple new ways to meet and interact with others.

It is not just the number of relationships people have, but the quality of their relationships that impacts health.[5] Health is influenced by the number of close confidants a person has —not only the number of people they know or the number of friends they have in general.[6] A confidant is someone with whom a person could discuss personal health matters. In a study of older women, having no confidant was linked to a reduction in physical functioning and vitality that was as strong as the effect of being a heavy smoker or being overweight.[7] Social isolation (few social ties, infrequent social contacts), loneliness (a more subjective emotional state), and living alone all result in similarly increased mortality irrespective of gender, length of follow-up, and geographical location.[8]

It would seem, despite some controversy around research data, [9] that the average number of confidants per person has been declining significantly.[6] Data comparing average numbers of confidants per person between 1985 and 2004 reported a drop by one-third, from an average of 2.94 confidants down to 2.08.[6]

Participation in the community has decreased as well. Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, noted in 1995 that the number of Americans reporting that they had “attended a public meeting on town or school affairs” fell from 22% in 1973 to 13% in 1993.[10] People participate less in voting, labor unions, parent-teacher associations, and community groups.

Advances in technology—namely via mobile phones and online social networks—are also changing how people relate to each other. A 2009 report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project concluded the following:[11]

- Compared to 1985, there has actually been minimal change (as opposed to what was suggested by the McPherson study cited above) in some measures of social isolation. Twelve percent of Americans have no confidants. Six percent of the adult population report that they have no one who is “especially significant” in their lives.

- The Pew report agrees that the average size of Americans’ core discussion networks (discussion networks are a measure of meaningful social connections) has decreased by one-third.

- However, owners of mobile phones and those who are active on the Internet have larger and more diverse discussion networks. They do not seem to frequent public places less; in fact, many people use the Internet in public places. They also tend to be just as likely to talk to their neighbors in person or to be involved in civic activities as non-Internet users.

The use of social media stands at approximately 8.9 billion active accounts between the 6 most popular sites, topped by Facebook with 2.2 billion active users. [12] The impact on wellness and connection of the use of these websites is not easily discernable. Their impact on depression and well-being for a given user is greatly influenced by psychological, social, behavioral, and individual factors.[13] Only time will tell if these sites become tools to maintain meaningful relationships, if they will increase superficial interaction that inhibits deeper connection, or something between.

Relationships and Research: Different Ways to Connect

Love and intimacy are the root of what makes us sick and what makes us well, what causes sadness and what brings happiness, what makes us suffer and what leads to healing.[14]

Animal studies

The healing power of social connection began to receive research attention in the 1960s and 1970s. A variety of research involving numerous animal species found that if animals are exposed to a stressor, their health is less likely to deteriorate if they are in the presence of familiar cage mates, rather than alone. In fact, a stressor that would increase blood cortisol levels by 50% in an animal that is alone will not affect cortisol level when it is in familiar company.[15]

To learn more about benefits of relationships between animals and people, refer to the Whole Health tool, “Animal-Assisted Therapy.”

Human research

Similar effects have been found in many studies involving humans. A 2006 study evaluated functional MRI (fMRI) findings in women who were awaiting an electric shock.[16] Women who were alone, or those who held the hands of unknown strangers prior to being shocked, continued to have fMRI changes consistent with anxiety. Their stress hormone levels were increased. In contrast, women who held hands with their husbands, and who were in a marriage they rated highly in measures of mutuality (high levels of shared interests, feelings, thoughts, aspirations, and goals) felt less anxiety. Their fMRI findings showing less activity in the parts of the brain that were found to be active if they experienced the electric shocks either when they were alone or with a stranger.

These effects are not limited to the artificial environment of the laboratory. The Alameda County study, which followed over 7,000 residents of Alameda county for nine years, was one of the many studies that drove this point home.[17] It found that the best predictor of mortality in people over 60 was their level of social support. Having close ties to family members and friends was the best predictor of longevity of all the health variables studied.[18]

Furthermore, as was noted in a 2006 literature review of 29 studies, better social support correlates with better surgical outcomes.[19] A 1997 study found that people with limited positive relationships developed colds four times more frequently than others.[20] Just as positive support can be beneficial, negative social support can lead to worse health outcomes.[21] For example unhappy marriages led to 34% more coronary events, regardless of gender and social status.[22]

Significant others

In a five year follow-up study of 10,000 men with three or more risk factors for coronary artery disease, the men who answered “yes” to the question, “Does your wife show you her love?” had a 50% lower rate for the onset of angina than those who answered no.[23] The study also indicated that men who are shown love had half the incidence of ulcers.[24]

Other studies have shown that having confidants is the key; women experience similar benefits, and it stands to reason that people with good relationships with significant others, be they married or not, will benefit. Longevity is increased for men and women with cardiac disease who have someone with whom they can confide and share their life. A study of 1,400 men and women over a five year period who had experienced cardiac catheterization found that unmarried people who had no close confidant had triple the mortality rate.[25] Close personal relationships also have been found to decrease the risk of depression and mortality in the 18 month period following a myocardial infarction.[26][27]

As mentioned above, there are both buffering and aggravating/stressful influences of relationships on health depending on their nature. It may be that, in some cases, chronic stress is the inciting factor that decreases relationship quality. Most studies have not found a difference between married and cohabitating couples. However, it has been found that neurologic response to threat was attenuated by a spouse more than by a cohabitating partner even when matched on relationship length and quality. Being unhappily married is associated with worse health outcomes than being single, and negative partner interactions are associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and chronic illness. Spousal conflict is associated with poor pain tolerance and higher blood pressure and heart rate in addition to significantly worse cardiovascular outcomes, endocrine function, and immunity.[28] Improving relationships seems to improve mental health to a greater degree than mental health improves relationships (though that occurs as well).[29]

How individuals enter into relationships matters as well. Attachment insecurity (ie anxiety about or avoidance of attachment) is associated with dysregulated physiological responses to stress, risky health behaviors, susceptibility to physical illness, and poorer disease outcomes, psychological health, and well-being. These associations depend, in part, on the other partner’s attachment style and behavior.[30][31]

There are certain situations that can add stress to an intimate-partner relationship. The transition of couples into parenthood is associated with increased conflict, less leisure time together, less satisfaction with division of household labor, and decline in sexual satisfaction and intimacy. Understanding of this stress and bringing awareness of it early into the transition can help; encouraging more equal co-parenting can be beneficial to both parents.[32]

Certain characteristics in a committed partnership are more likely to foster true connectedness. A meta-analysis of 21 studies totaling 2,739 participants showed higher relationship satisfaction when empathetic accuracy (extent to which people accurately perceive their peers’ thoughts, feelings, and other inner mental states) was higher between couples, especially when it was higher for negative emotions.[33] Linkage (synchronization of people’s moment-to-moment physiological states) may confer benefits, but also may put couples at risk if they become entrenched in patterns of conflict or stress.[34]

Parental and adolescent relationships

The closeness of relationships with parents has a significant impact on health. For example, a study conducted at Johns Hopkins that looked at relationships with parents and disease in later life found that, when other variables were taken into account, cancer rates were higher for people who were less close to their parents.[35]

A 35-year follow-up of the Harvard Mastery of Stress Study followed health outcomes for 126 men.[36] These included coronary artery disease, cancer, hypertension, ulcers, and substance abuse. The study looked at each man’s relationship with his father and mother and whether it was “very close,” “warm and friendly,” “tolerant or strained,” or “cold.” When the relationship with one or both of the parents was “tolerant or strained,” a man was two times more likely to have significant health issues than one who had “warm and close” parental relationships. Men who had a “tolerant or strained” relationship with their fathers had an 82% likelihood of a significant health issue, and those with such a relationship with their mother had a 91% risk. The risk rose to 100% if both parental connections were lacking. Researchers concluded that healthy behaviors, coping styles, and spiritual values or practices developed in childhood due to warm and close relationships with parents led to improved health later in life.[36]

It has been known that divorce and domestic violence have a negative impact on a child’s psychopathology. More recent data also indicates that the quality of parental interpersonal interactions around conflict impacts the child’s emotional, behavioral, social, academic outcomes, and their own future interpersonal relationships.[37] In addition, challenges in managing conflict and hostility during adolescent years is associated with chronically elevated interleukin-6, a marker of immune system dysfunction, in their late 20s.[38]

Social networks, support systems, and community relationships

It is helpful for clinicians to recognize each individual as being influenced by his or her community as well. What resources are available (or not), be they social, political, cultural, or spiritual, also has an effect on health outcomes. Perhaps nowhere has the healing power of community been illustrated as clearly as in studies of Roseto, Pennsylvania.[39] Researchers noted that the town’s residents had a lower incidence of heart disease, despite being as likely to have multiple risk factors, such as poor diet and tobacco use. They described what made the community unique:

There was a remarkable cohesiveness and sense of unconditional support within the community. Family ties were very strong, and what impressed us most was the attitude toward the elderly. In Roseto, the older residents weren’t put on the shelf, they were promoted to the “supreme court.” No one was ever abandoned.[39]

Sadly, over the course of 50 years, as the community moved away from these patterns, the incidence of heart disease gradually rose to match that of the surrounding communities.

The concept of “social capital” comes into play here. Social capital involves all the benefits that are expected to come when a person participates cooperatively with others, either in individual relationships or within groups.[40] By offering support to others, one increases the chances of receiving support in the future. A 2012 review of multilevel studies of social capital and health found that social capital did have positive effects on health outcomes but noted that there is a need for more research.[41] A 2014 review of 17 studies found a positive correlation between social capital and chronic disease prevention.[42] It seems that even the health risks associated with poorer socioeconomic status are attenuated by stronger social connections. [43]. A 2008 study of 944 pairs of twins found that higher ratings for individual-level social capital variables—social trust, volunteer activity, community participation, and sense of belonging—correlated with better mental and physical health.[44] Ideally, health care programs can work in conjunction with community groups to optimize the provision of health in a community, doing what they can to augment the effects of community efforts.

The Experience Corps, initially started in Baltimore, Maryland, is an excellent example of a program that improved health at many levels within a community—individuals, schools, and the community as a whole.[45] The program brings elderly volunteers into public elementary schools with the goal of creating an impact on the educational outcomes of children, while simultaneously improving the health and well-being of the volunteers.[46] Children, parents, teachers, and residents within the community were all involved. Research indicates that health promotion programs that focus on bringing benefit to a community as a whole have better health outcomes than programs targeting only individual health behaviors.[47]

Another novel program aimed at enriching social connection and improving health is the Community Men’s Sheds (CMS), developed in 1978 in Australia. There is an intentional effort to provide men with biopsychosocial support; this increases self-esteem and empowerment, offers respite from families, enhances the sense of belonging in the community, and offers them the opportunity to exchange ideas related to personal, family, community, and public health issues. Most CMS have a woodworking area, trade tools, and equipment next to a “tea room;” some even provide support for men with mental health or physical disabilities or support youth and the unemployed.[48] Evidence indicates these facilities create a space in which interaction and support can help overcome many social, health, and well-being concerns.[49]

As we learn more about the importance of connection and health, organizations have begun to use volunteers to support vulnerable community members. A review of 14 trials including 2,411 participants indicated that volunteer befriending programs seem to improve symptoms of depression, anxiety, mental illness, cancer, physical illness, and dementia—although not always to a level of statistical significance. However, they did seem to have a statistically significant improvement on patient-reported outcomes.[50]

Relationships and Research: Effects on Specific Illnesses

COPD

A 2015 review of 31 studies indicated that mental health and self-efficacy were consistently better in those COPD patients with good social support.[51]

Heart Disease

- Family support in heart failure patients influences self-care behaviors and chronic disease self-management. It positively influences decision-making processes related to management of symptoms and inquiries about treatment options.

- Better-quality relationships between heart failure patients and their informal family caregivers results in reduced mortality, increased health status, less distress, and lower caregiver burden.[52]

- The health-related quality of life of patients with left ventricular assist devices is significantly improved with higher social support.[53]

Diabetes Mellitus

- A review of 35 studies found that connection, especially to family, was important to people with type 2 diabetes. Participants used a variety of technologies to connect with their health care team and other people with the same disease. This type of connection seems to improve objective measures of disease control (hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol) and risk factors (body weight, physical activity, healthy eating).[53]

- A study of 700 veterans in the Pacific Northwest found that diabetes-specific social support was associated with better adherence to diabetic diet and regular physical activity.[54]

- Diabetics also seem to have better disease control in the setting of trusting relationships with clinicians and health teams.[55]

Mental Health

- People seek out grief groups for support and sharing. Groups seem to improve well-being, but there is disagreement as to whether it decreases symptoms of grief. Therapeutic factors related to sharing and support, interpersonal learning, and meaning-making all have some potential to affect grief outcomes and well-being for those with and without symptoms of complicated grief (CG). Some processes may also affect outcomes indirectly by influencing group member behaviors such as treatment engagement, which can be low among individuals with CG.[56]

- Social support from research personnel, healthcare professionals, family members, and peers plays an important role in initiating and maintaining physical activity in individuals with schizophrenia.[57] This is very important given the metabolic risks of many of the antipsychotic medications.

- Female Veterans returning from deployment are at high risk of depression when social support needs and concerns about financial status are high.[58]

- The risk of PTSD, anxiety, and depression after exposure to natural disasters or conflict-affected settings is decreased by greater social capital.[59]

- More satisfactory social support positively impacts outcomes of depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, and anxiety disorders.[60]

- Social support is extremely important for the successful recovery from severe mental illness and substance misuse.[61][62]

Cancer

- A meta-analysis of 15 studies showed that more insecure attachment style is associated with poorer outcomes in terms of psychological adjustment to the cancer diagnosis and ability to perceive and access social support. Caregivers with insecure attachment style have more depression, higher stress levels, decreased motivation for care-taking, and increased difficulty with caregiving.[63]

- Lower levels of social support increase inflammation, pain, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors.[64]

Mechanisms of Action: Physiological Effects of Relationships

Mirror neurons

It is clear that relationships affect health. How are these effects mediated? One potential answer is that mirror neurons play a role. Mirror neurons are a class of neurons discovered just over 20 years ago by an Italian research team.[65] The team noted that when a macaque watched another macaque perform an action, its brain would activate on imaging studies the same way that it would when the macaque performed the action itself.

Subsequent studies have demonstrated that humans also have mirror neurons[66], and it has been observed that these neurons respond not only to observed movements of others, but also emotional states and tactile experiences of others who are being observed.[67] If a person observes another person experiencing disgust because of a bad smell, the observer’s brain will activate as though he or she is also feeling disgust.[68] The same thing occurs if a person sees another person experiencing soft touch; the touch center of the observer’s brain becomes active in the area corresponding with the part of the body observed being touched in another person.[69] This has been referred to as “tactile empathy.” It would seem it is built into our brains to be able to establish rapport with our fellow humans. In fact, it is possible to tell two people are in rapport because their posture, vocal pacing, and movements become synchronized.[70]

The details of how motor neurons are related to empathy are still being elucidated. When a person witnesses facial cues and body postures associated with emotion in another person, the people with the highest empathy scores also have proportionately higher activity in areas of the brain containing mirror neurons. Mirror neurons seem to activate a system of understanding another’s experience that happens without cognitive or reflective effort. Some propose that these neurons allow a sort of inner imitation of another’s experience or a resonance of the minds of the observer and the observed.[71]

Inflammation

There is a growing body of research showing a direct link between the quality of a person’s relationships and levels of inflammation in the body.[72] A US study followed the relationship quality of 647 adults over 10 years and measured markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, fibrinogen, E-selectin, and intracellular adhesion molecule-1). The investigators found that support from family, friends, and spouses was associated with lower inflammation levels. They noted that relationship stress with these individuals increased inflammation and that the stress was a stronger influence on inflammation than the positive impact of supportive relationships.[73] These findings were further supported in a meta-analysis of 41 studies including 73,037 participants which showed that social support was inversely correlated with levels of inflammatory biomarkers.[74] People with cold, unsupportive, and conflict-ridden relationships have more chronic inflammation.[75] It has even been found that past troubled relationships, not only current ones, can have a lasting impact on levels of inflammation.[75]

How does the impact of relationships result in this inflammation? Exposure to stress causes the release of hormones from the hypothalamus, leading to increased release of cortisol. This in turn results in transcription of genes that suppress immune function and increase inflammation. However, exposure to chronic stress, say in a dysfunctional relationship or chronic loneliness, causes the body to resist the hyperactivation by cortisol, leading to changes in baseline levels of cortisol and glucocorticoid receptor resistance. This decrease in the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol results in increased chronic inflammation, which is associated with increased disease frequency, severity, mortality, and poorer subjective health ratings.

Negative experiences with relationships (negative expectations, hostility, anger, negative marital interactions) tend to intensify the stress response and have been associated with outcomes such as worse immune function, delayed wound healing, more arterial calcifications, higher blood pressure, and worse asthma, as well as higher incidence of strokes, heart attacks, and ulcers. In contrast, positive relationship experiences are associated with less cortisol reactivity in stressful situations, even in the setting of low socioeconomic status. They are also linked to, healthier diurnal cortisol slopes, lower blood pressure, and decreased risk of re-hospitalization and death from cardiovascular disease.[76]

Oxytocin

Several researchers have theorized that oxytocin is the critical link between connecting with others and health. Oxytocin levels increase in a mother when she gazes at her child, in a father when he touches his child to initiate play, and in someone who hears the comforting voice of his/her mother in conversation after a significant life stressor. Exogenously provided oxytocin increases social engagement of fathers with their toddlers, which in turn increases the toddlers’ endogenous oxytocin levels. This reciprocal effect was also seen between a dog owner and dog when the dog was given oxytocin. Intranasal oxytocin led people to rate their partners as more attractive.[77] These studies clearly show that oxytocin lives up to its nickname of “the love hormone.”

Oxytocin impacts the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by inhibiting cortisol release; this effect is enhanced by social support from close relationships. Oxytocin also acts in the brain stem to regulate vagal output. Exogenous oxytocin increases respiratory sinus arrhythmia (a marker of favorable vagal tone) and may decrease blood pressure. Exogenous oxytocin can reduce the inflammatory cytokines of a bacterial infection—possibly via modulation of vagal output. Blocking oxytocin receptors in rats prevents the positive effects of social housing. Oxytocin in animal models protects against myocardial infarction, hypertension, and obesity. Women who suffered childhood abuse have less oxytocin in their cerebral spinal fluid as adults and men with a history of early life stress have lower serum oxytocin levels. Children of mothers who frequently withdrew love, have less altruistic behavior after receiving oxytocin as adults—perhaps because of a reduced investment in social bonds.[77]

Gathering Information: Learning More About Veterans' Social Support

Illness may prohibit individuals from having access to their support system or being able to socialize in their usual way. When people are in pain, they often withdraw from others in order to conserve inner resources and physical energy, and they may not ask for the help that they need. Clinicians can inquire about Veterans’ current social support resources and help them to pinpoint where there is a need for additional support and to identify how it might be met.

After a clinician has reviewed answers to questions about family, friends, and co-workers from the PHI, other questions can take the conversation about relationships and social supports deeper. As noted earlier, social support has three dimensions, and all of them are important. Consider asking about all three:

- Who provides you with support?

- How satisfied are you with the support? A negative relationship may be worse than no relationship at all.

- What types of support do you receive? Social support can be emotional or instrumental (i.e., involves receiving labor, time, or funding from others). It may also involve receiving mentoring (feedback) or information.

The Social Support Questionnaire, developed in 1983, contains 27 questions that can be used to gather more information about social support – who provides it, the type of support a person receives, and how satisfied a person is with that support.[78] If individuals are not “very satisfied” or “fairly satisfied,” it is worth exploring their answers in more depth, if possible. The following questions are from the six-item short version of that questionnaire.[79]

- Whom can you really count on to be dependable when you need help?

- Whom can you really count on to help you feel more relaxed when you are under pressure or tense?

- Who accepts you totally, including both your worst and your best points?

- Whom can you really count on to care about you, regardless of what is happening to you?

- Whom can you really count on to help you feel better when you are feeling generally down-in-the-dumps?

- Whom can you count on to console you when you are very upset?

And here are some other key questions you can consider:

- Which relationships fulfill and/or strengthen you?

- Do you have a significant other?

- If single: Are you satisfied with being single, and do you have the support you need in your life?

- Are you sexually active? Are you satisfied with this aspect of your health, and why or why not?

- Do you feel supported by your partner?

- Do you have any children? What ages?

- What activities do you and your partner do together?

- Is anyone hurting you? (Never forget to ask about safety at home, as noted in Chapter 6, Surroundings) Have you been hit, kicked, punched, choked, or otherwise hurt by an intimate partner?

- Do you get the support you need from your loved ones?

- Are you lonely?

- How often do you share your feelings and thoughts with others?

- Who or what drains your energy? Can you change this?

- Do you have friends or family members you can talk to about your health?

- What do your partner and family think are the causes of your health issues?

- Has an illness of a loved one ever affected you? Are you taking care of anyone with chronic illness?

- Is there someone you would like to have come with you to your health care appointments?

- Are you close to your blood relatives (parents, siblings, extended family, children)?

- Who do you consider to be your “family of choice?” Is it your blood relatives? Who else is important to you in your life?

- How deeply are your family members involved in each other’s lives?

- Tell me about your closest friend. What do friendships mean to you?

What Clinicians Can Offer: The Therapeutic Relationship

The ideal practitioner-patient relationship is a partnership, which encourages patient autonomy and values the needs and insights of both parties. The quality of this relationship is an essential contributor to the healing process.[80]

As noted in the overview “Whole Health in Your Practice, Part II: The Power of Your Therapeutic Presence,” we as clinicians can do better at enhancing the therapeutic relationship. Recall the study mentioned earlier where Veterans who had attempted suicide noted that one of the most important things the VA could offer to decrease suicide risk is stronger therapeutic relationships.[1] We know that healing relationships with clinicians improve patient quality of life, because they instill in patients a sense of hope and trust. Better relationships are also linked to decreased morbidity and mortality and better clinical outcomes.[81][82]

Acts of kindness such as deep listening, empathy from care team members, generous acts of effort that go beyond what the patient expects, timely care, gentle honesty, and support for caregivers are all important pieces of health care that decrease the emotional turmoil of cancer for patients, caregivers, and clinicians.[83] When therapists’ empathic abilities are lacking, rates of therapeutic dropout increase; when present, it beneficially influences the patients’ lives and behaviors.[84] Finally, strong therapeutic relationships enhance clinician resilience and allow them to avoid burnout, not to mention reduce the risk of malpractice lawsuits.[85]

In 2005, Kaiser Permanente identified key aspects of the approaches they took to enhance clinician communication and relationship skills.[86] They outlined a “Four Habits Model,” which included the following:

- Invest in the beginning.

-

- Create rapport quickly. Introduce yourself to everyone in the room, acknowledge the wait time, and put the patient at ease.

- Elicit the patient’s concerns using open-ended questions.

- Plan the visit with a patient. Let her/him know what to expect and prioritize as needed.

- Elicit the Patient’s Perspective.

-

- Ask for the patient’s ideas about what is going on and what is concerning her/him most, as well as what she/he has already done to address the concerns.

- Elicit specific goals in seeking care.

- Determine how the illness has influenced the patient’s life.

- Demonstrate empathy.

-

- Be open to the patient’s emotions.

- Make empathic statements, e.g. “You seem frightened.”

- Use nonverbal communication to convey empathy.

- Invest in the end.

-

- Deliver diagnostic information.

- Educate the patient, eg explain why tests or treatments are being done, discuss potential side effects, course of recovery, and resources that can be used.

- Involve the patient in decision-making.

- Complete the visit by summarizing the visit and next steps, asking if the patient has other questions, and verifying that she/he has received what is needed.

Sympathy

Sympathy involves feeling concern and understanding for the suffering of others, whereas empathy goes beyond that. Empathy is the ability to mutually experience emotions, direct experiences, and thoughts of others [87], while recognizing appropriate boundaries; one reaches into another’s experience without getting caught up in it.[88]

In 1968, Wilmer shared his perspectives on empathy:

If there is empathy there is real understanding of the other as another person. Here we understand his suffering in relationship to his personal and social world. We share, we feel for him and with him; psychologically, we get inside him for the purpose of understanding how he feels. In empathy it is as if “I were him.” To achieve an empathic relationship, we use ourselves as the instrument for understanding, but by the same token we keep our own identity clearly separate. In this situation the observer guards against his biases and misperceptions, and must thereby understand himself.[89]

Empathy occurs in a clinical encounter when a clinician clearly demonstrates he or she relates to a patient’s experience. The clinician may have an awareness of feelings, emotions, sensations, conceptions, convictions, hopes, and fears that the patient is experiencing regarding the disease or illness and options for recovery. A healthy approach for clinicians is to continue to engage in their own self-care practices and to be aware of personal and professional biases that interfere with authentic connection with the patient. When a clinician experiences increased symptoms of burnout or compassion fatigue, depersonalization increases and empathy decreases. It is vital to be aware of this if it is beginning to occur.[90]

Compassion

It’s not how much you do but how much love you put into the doing that matters.

—Mother Theresa

Once we are able to recognize the importance of empathy, we can begin to generate a sense of compassion for one another. Gelhaus holds that empathic compassion involves an appreciation for the common worth and dignity of all beings, noting that it can be taught.[88] He states that the following characteristics need to be present for a compassionate response:

- There is recognition of the situation and the suffering related to it.

- There is benevolence or kindness.

- It is directed toward a person.

- There is a desire to relieve suffering.

Most training programs for health care professionals give little emphasis to the cultivation of compassion in trainees. In fact, by selecting students based on certain academic criteria, personality traits, or educational institutions, they may screen out people with high levels of compassion in favor of less compassionate people who display high levels of ambition, strong test taking skills, or other traits.

Many mindful awareness training programs include what is commonly referred to as a Compassion Practice, or Loving-Kindness Meditation. Currently, there are VA clinicians who are enrolled in the Compassion Cultivation Training Teacher Certification Program through the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University.[91] Another notable program within the VA is led by Dr. David Kearney and Tracy Simpson; it is a 12-week pilot program that began in 2010 at the Seattle VA and is teaching Loving-Kindness Meditation to Veterans dealing with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[92] Refer to the “Compassion Practice” tool for a sample meditation you can try yourself or use with patients.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Feeling Compassion

Think of a patient (or other person in your life) who is struggling in some way. Send that person an affirmation:

- May you be safe.

- May you be happy.

- May you be healthy.

- May you be peaceful.

As you focus on these intentions for them, what do you notice? Do you feel a particular sensation in your body? What emotions come up? We often speak of our compassion for others being “heartfelt.” What do you notice in your heart as you think of this person? There is no right or wrong answer; the key is simply to take notice.

As noted in the Whole Health Library’s “Mindful Awareness” overview, research has found that regular meditation practice leads to lasting changes in brain activity.[93] A 2014 systematic review, while noting that further research is needed, found that “kindness-based meditation” led to decreases in depression, increased mindful awareness, greater compassion toward others and toward oneself, and more positive emotions.[94]

What Clinicians Can Offer: Recommendations for Personal Health Plans

In addition to doing all they can to create a healing therapeutic relationship predicated on empathy, compassion, and the various components of the “Four Habits Model,” there are other ways clinicians can help Veterans have positive relationships with family members, friends, and co-workers. Examples include the following:

- Encourage patients to try Compassion Meditation (as described in the “Compassion Practice” tool).

- Explore with patients their positive—and negative—social supports, discussing how they might increase their exposure to the former and decrease it for the latter. Clinicians should consistently screen for domestic violence. Elder abuse must always be considered as a possibility for older Veterans.

- Involve social workers on the health care team. Social workers can prove invaluable allies in many ways. For a Veteran-friendly description of what social workers do, refer to the VA Social Work pages. Social workers and case managers can match people up with the programs that can prove most helpful to them.

- Learn about support groups in your facility and in your patients’ communities. There are many online support groups available. The National Center for PTSD lists some resources for those with PTSD, as well as general resources for finding support groups focused on a variety of other areas.

A 2016 review focused on peer facilitator and support group outcomes found only 1 of 9,757 studies met inclusion criteria, noting that more research is needed.[95] One study of patients with malignant melanoma found that those who participated in a six-week support group after the removal of malignant melanoma had half the rate of recurrences and a third of the mortality rate when compared to the control group at five years follow-up.[96] Internet support groups are very popular, and also show some evidence of benefit on social support and self-efficacy.[97]

- Encourage Veterans to become involved in volunteer work. We know that volunteer work enhances well-being in a number of ways.[98] A research report on the health benefits of volunteering is available from the Corporation for National and Community Service.[99] Older adults who give love and support to others have significantly fewer health issues.[100] Refer to the section on volunteer work in the “Personal Development” overview for more information.

- Encourage Veterans to find ways to become more active in their local communities. Examples include the following:

-

- Attending community events, such as civic celebrations, theater performances, or fundraisers

- Helping to direct or organize community events (e.g. joint a steering committee or board)

- Participating in the arts in the community

- Attending local sporting events

- Joining a religious or spiritual community

- Taking a course of some kind

Back to Michael

During a session with Michael, his physical therapist commented on how much he seems to care about his current family and fellow Marines. Michael mentioned this to a nurse on his primary care team. After some discussion, and with Michael’s buy-in, they helped him create a Personal Health Plan (PHP) that focused on Family, Friends, & Co-Workers

Michael continued to work through the cardiac rehabilitation program. In addition to learning more about exercise and nutrition, he also learned more about emotions, communication skills, and mindful awareness during a Whole Health course he signed up for. He began trying to open up more to his wife and asked her to attend some classes and counseling sessions with him so that they could learn together, which she was happy to do. He started working with Mental Health more regularly and was introduced to meditation.

A few months later, Michael took an eight-week class on mindful awareness and compassion that was offered at his VA facility with minimal charge to him. It made him feel a bit uncomfortable at first, but he enjoyed it over time. He found himself sharing more about his emotions and thoughts to his wife, daughter, and friends. He started to meet with a group fellow Veterans from the cardiac program. They started walking together twice a week. He also began volunteering in a local literacy program for children with reading difficulties. For the first time in years, he and his wife have been “going out with friends,” and it is clear he is glad that this is the case. He looked up a few of his old Marine buddies, who he had not seen in over 10 years. He makes a point of calling his daughter and her family at least once every 2 weeks, and he and his wife are saving up to go visit them in California.

A few years later, Michael is training to be a Whole Health Specialist, so that he will be able to help his fellow Veterans with Personal Health Planning. He completed a PHI again recently and was pleasantly surprised when he realized he gave himself a 4 on “Where I am Now,” as well as a 4 on “Where I Want to Be.”

Whole Health Tools

Resources

- DoD/VA Suicide Outreach: Resources for Suicide Prevention and Crisis Line

- Access to hotlines, treatments, professional resources, forums, and multiple media designed to link individuals to others. This site supports all Service Branches, the National Guard, the Reserves, Veterans, families and clinicians.

- Veterans Crisis Line

- To receive confidential support 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, Veterans and their loved ones can 1) call 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1 or 2) chat online or 3) send a text message to 838255

- DCoE Outreach Center

- The Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) runs a resource center that provides information and resources about psychological health (PH), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and traumatic brain injury (TBI). The center can be contacted 24 hours a day, seven days a week 1) by phone at 866-966-1020, 2) by email at resources@dcoeoutreach.org, or 3) by-online chat.

- National Call Center for Veterans who are Homeless

- For a Veteran who is homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (also intended for Veterans’ families; VA Medical Centers; federal, state, and local partners; community agencies; service providers; and others in the community). 1-877-4AID VET (877-424-3838)

- Military OneSource

- Military OneSource is a free service provided by the Department of Defense to Service Members and their families to help with a broad range of concerns. Call and talk anytime, 24 hours day/7 days a week at 1-800-342-9647.

- National Center for PTSD Support Group Page

- The National Center for PTSD lists resources for those with PTSD, as well as general resources for finding support groups focused on a variety of other areas.

- National Resource Directory (NRD)

- The NRD is a website for connecting wounded warriors, Service Members, Veterans, and their families with those who support them. It provides access to services and resources at the national, state and local levels to support recovery, rehabilitation and community reintegration. Visitors can find information on a variety of topics including benefits and compensation, education and training, employment, family and caregiver support, health, homeless assistance, housing, transportation and travel, and other services and resources. The NRD is a partnership among the Departments of Defense, Labor and Veterans Affairs.

- VA Caregiver Support

Programs available both in and out of the home to help caregivers support Veterans and themselves.

Additional Resources

- David Kearney and Tracy Simpson, Loving-Kindness Meditation Video Clip

- Compassion: Bridging Practice and Science, Stanford University, e-book

- Center for Investigating Health Minds, Richard Davidson

Author(s)

“Family, Friends, & Co-Workers” was written by Christine Milovani, LCSW and J. Adam Rindfleisch, MPhil, MD, and updated by Greta Kuphal, MD. (2014, updated 2019)