Spirit & Soul is an element of Self-Care in the Circle of Health that can mean many things to many different people. When all is said and done, the focus is on what brings meaning and purpose into a person’s life. When a Whole Health Personal Health Plan (PHP) is being created, the focus may be on a person’s religious beliefs, their spiritual perspectives (which may or may not be linked to religion) or to other aspects of their lives that tie into “what life is all about.” This overview builds on Chapter 11 of the Passport to Whole Health, focusing on how Spirit & Soul can best be discussed in the case of a particular Veteran.

Key Points

- Always take time to frame care in terms of what really matters to someone. Develop a sense of what gives someone’s life meaning and purpose, and let that guide personal health planning.

- Most patients want to talk about their spiritual and religious beliefs with their clinicians, but they do not if they feel their clinicians will not know what to do about their concerns.

- Most clinicians are not trained in discussing spirituality and do not bring it up, unless perhaps end-of-life decisions are being made. Leave room for Spirit & Soul in your conversations.

- When exploring Spirit & Soul, it helps to have a framework for gathering information. There are many mnemonics, like IAMSECURE, that cover a variety of potentially useful topics.

- Research has found that religiosity and spirituality favorably affect coping skills, the severity of many health concerns, coping, and healthy lifestyle choices. Examples of conditions that benefit include depression, anxiety, coronary artery disease, HIV, elevated blood pressure, substance use disorders, and chronic pain.

- Pathologies of the spirit— e.g. spiritual guilt, spiritual anger, and spiritual despair—are important to discuss, when appropriate. The effects of moral injury on Veterans’ health should also be addressed.

- Chaplains make excellent members of the Whole Health team. Their presence enhances patient satisfaction and is associated with improved patient outcomes.

- There are many Spirit & Soul tools and skills you can suggest. It can help to discuss forgiveness, spiritual anchors, and ways a Veteran can start a spiritual practice. Discussing coping helps. To more fully support others (and because your self-care is vital in and of itself), it is vital you explore your own beliefs and truths as a clinician.

Meet the Veteran

During your typical hospital workday, you stop in to see Eric, a Marine Corps Veteran and 29-year-old father of three. Eric was admitted with pneumonia yesterday after he failed a trial of oral antibiotics. He is steadily improving and will likely be discharged in a few days.

Eric is a Veteran of Operation Enduring Freedom. He was honorably discharged after being shot in the left leg. His leg was saved by a vascular surgeon, but he was told that he will walk with a limp for the rest of his life. When you ask him how his leg is doing, he acknowledges that it hurts. Then, in a lower tone of voice, he mentions that it is not so much his leg wound, but “all the other wounds that no one can see that hurt the most.” You ask him what he means, and he just shrugs his shoulders, saying, “Never mind. It’s okay. I know you are really busy. I don’t want to keep you.”

Eric’s wife, Julie, who is in the room with him, mentions that one of the most important things in Eric’s life before he left for Afghanistan was his faith. He was involved with his church, and he was “very spiritual.” When you ask what she means, she tells you that he used to get a lot of strength from praying, was always very kind and helpful to others, and was a very hopeful and grateful person. “Now,” she says, taking a quick sideways glance at her husband, “things are different.”

Eric nods his head and looks away.

One of your colleagues asked Eric to complete a Brief PHI when he was first admitted. A few of his answers stand out as you review it.

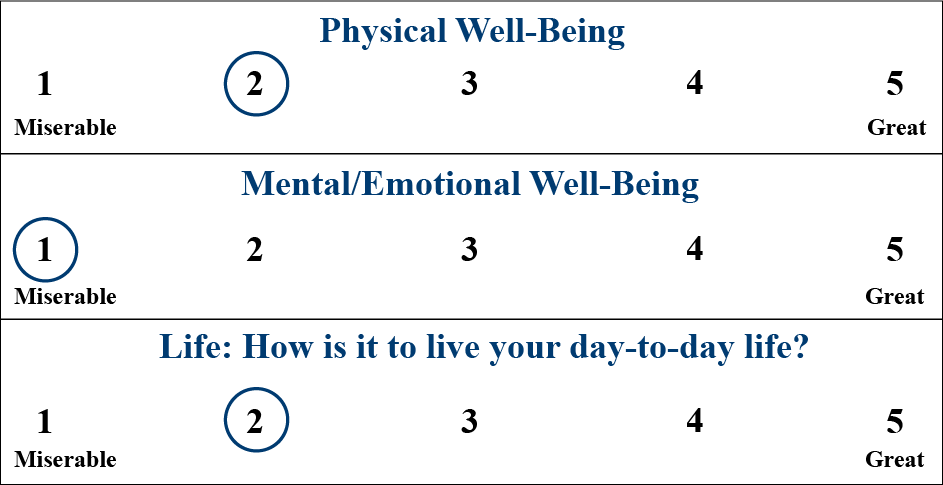

1. He rates himself pretty low on all the Vitality Signs:

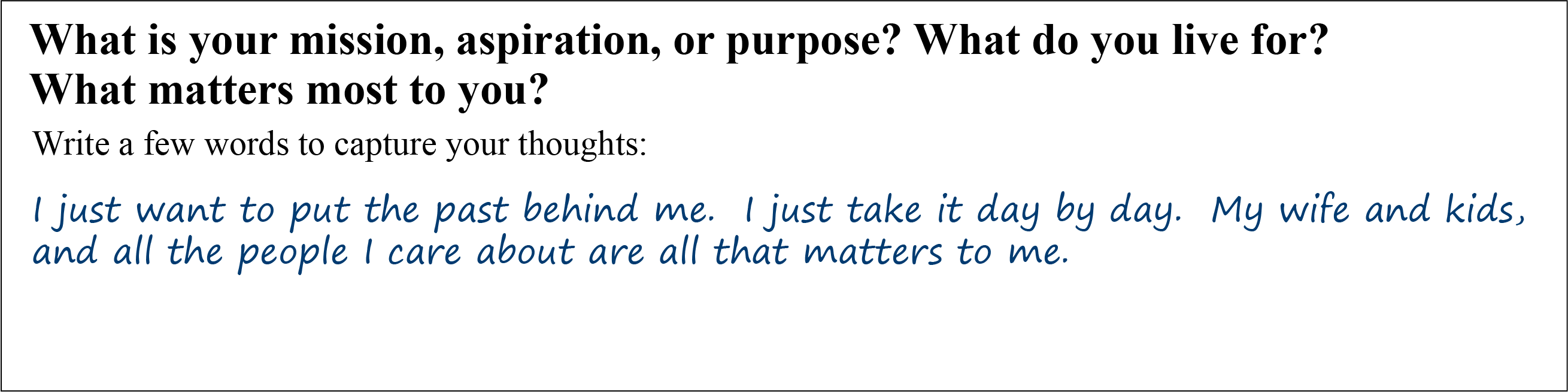

2. He has a unique answer for the question designed to capture Mission, Aspirations, and Purpose (MAP):

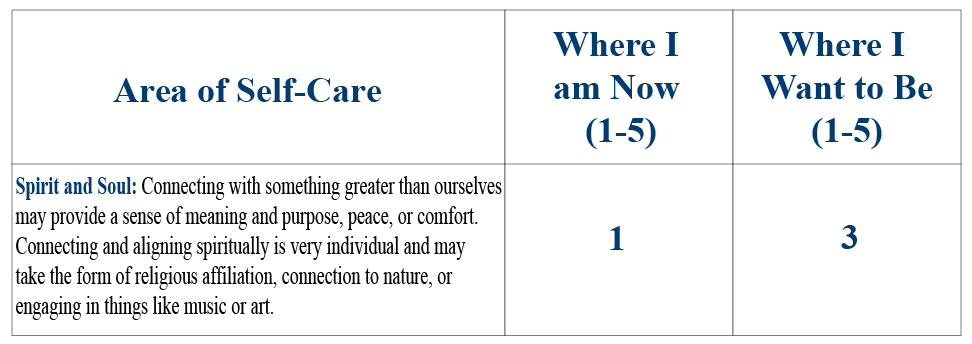

3. Eric gives himself a 3 out of 5 on every self-care item but Spirit & Soul:

3. Eric gives himself a 3 out of 5 on every self-care item but Spirit & Soul:

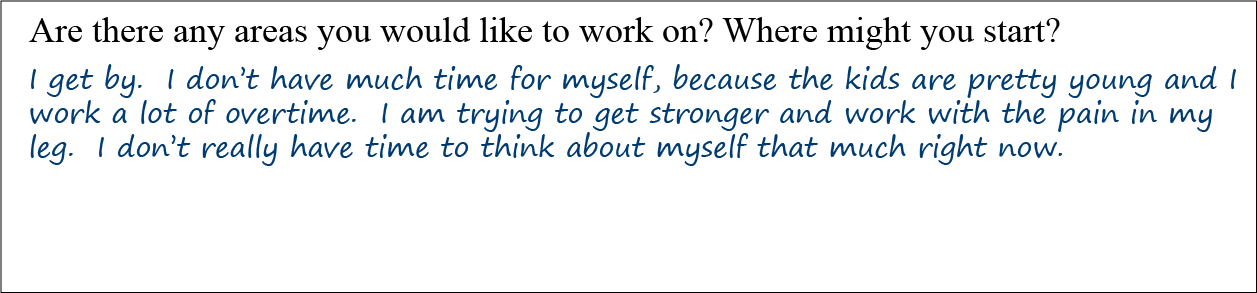

4. The final question on Eric’s Brief PHI is not too revealing:

Mindful Awareness Moment

Responding to Eric and Julie

Take a moment to consider how you would respond to Julie’s concerns about Eric. Options could include:

- Not pursuing the topic further because you feel uncomfortable

- Telling them to discuss this with his primary care clinician

- Calling in someone from Eric’s religious community, if possible

- Asking the hospital chaplain for help

- As time allows, asking him if the two of you can explore his spirituality in greater depth, either now, or after you have completed rounds, or at some other point

- Some combination of the above

- Something else not listed here

Which answers did you choose, and why?

Introduction

The twenty-first century will be all spiritual or it will not be at all.

—André Malraux

Different clinicians choose to approach the topic of spirituality with their patients in different ways. How you choose to approach concerns such as those brought up in the narrative about Eric and Julie will be informed by many factors, including:

- Your level of awareness about research related to spirituality, religion, and health. This is discussed in more detail below.

- How much time you have. Time constraints can be a challenge, especially on a busy inpatient service.

- Your comfort level.

- Knowledge of the resources available to you in your practice, ranging from hospital chaplains and local clergy to online and printed resources focusing on spirituality and health.

- Your own personal beliefs and perspectives surrounding spirituality, and how those have been shaped by your personal experiences and self-exploration. This is not to imply that all clinicians must have a specific perspective, or that it is appropriate to encourage their patients to share those beliefs. However, it is helpful, when working with patients, to have thought through your own ideas about tough questions such as:

- Why do we exist? What is the meaning of life?

- Why there is suffering?

- What do you believe happens (if anything) after a person dies?

- Would you pray with a patient, if you were asked to?

- Is there a God or Higher Power?

To explore your beliefs in greater depth, refer to, “Assessing Your Beliefs about Whole Health.”

Regardless of your perspective, paying attention to the perspectives of Veterans and others related to these issues with will enhance your ability to offer whole-person care to your patients, including the ones, like Eric, who have “invisible wounds.”

Why "Spirit & Soul" Matters

Spirit & Soul are linked with PHP in many ways:

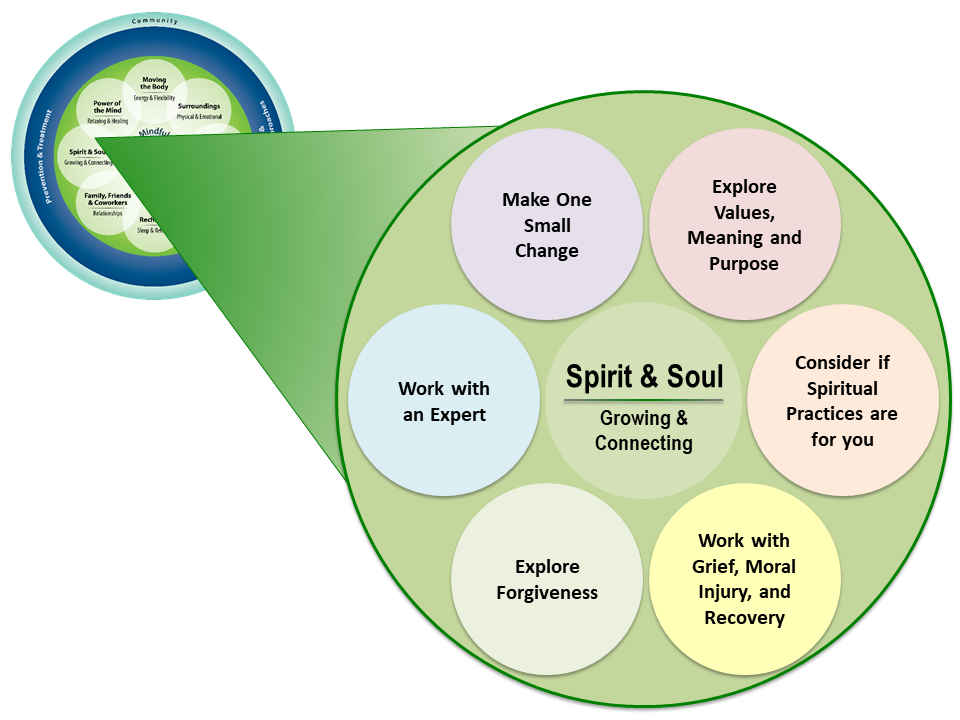

- Spirituality is an important aspect of self-care. Whole-person care requires that it be included along with all the other aspects of who a person is. It has its own green circle in the Circle of Health (Figure 1).

- Conversations about Spirit & Soul bring more depth and richness to patient visits. Meaning, values, suffering, death, and life purpose – various existential questions – cannot be overlooked in health care without our work losing some of its meaning.

- For many people, Spirit & Soul helps to define mission, aspirations, and purpose (MAP). It is at the core of why they want to be healthy in the first place.

- Spirituality informs therapeutic approaches, particularly those classed as complementary and integrative health (CIH)[1], which are woven into the Whole Health approach.

This overview reviews some of the latest research surrounding spirituality, religiosity and health. It is clear that both have a significant influence. A 2011 meta-analysis compared health effects of high levels of spirituality and religiosity to the effects of a number of other preventive health measures.[2] The authors reported an 18% reduction in mortality for people who report being religious and/or spiritual. This is equivalent to the cardiovascular benefit one gets from consuming healthy amounts of fruits and vegetables. In fact, having high levels of religiosity/spirituality has as much benefit (or more) as:

- Air bags in automobiles

- Taking angiotensin receptor blockers for chronic heart failure

- Screening for colorectal cancer using fecal occult blood testing

- Prescribing statin therapy for people without heart disease

- Out-of-hospital defibrillation

- Exercising

- Quitting smoking

- Getting a flu shot each year

This is not to downplay the importance of those other interventions; it is simply to say that spirituality matters to health too, and research has found measurable benefits.

Figure 1 highlights some of the topics that could be covered when incorporating Spirit & Soul into a PHP. This overview explores all of them in more detail.

Defining Spirituality, Soul, and Religion

Just as a candle cannot burn without fire, men cannot live without a spiritual life.

– Buddha

Before focusing more on research that might inform your practice, it is important to clarify some definitions. Roger Walsh, MD, author of Essential Spirituality, defines spirituality as the “…direct experience of the sacred.”[3] Fred Craigie, PhD, who teaches widely about spirituality in medicine, defines spirituality simply as, “What life is about.”

Soul, in its most general sense, is what makes something or someone alive. For some people, this can be related to a part of something or someone that survives after its body dies. Some people relate it to energy or vitality. For some, it ties into what brings meaning and purpose to existence.

Religion, in contrast, has been described as “…a body of beliefs and practices defined by a community or society to which its adherents mutually subscribe.”[4] Religiosity, a term used frequently in research studies, is the quality of having strong religious beliefs or feelings.

Religion is important to many people. Among all US adults, 77% subscribe to a religious tradition. Roughly 71% of those are Christian, 5% are other religions (Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu), and 23% are unaffiliated (atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular”[5]). Of the unaffiliated people, 18% described themselves as religious, 37% said they were spiritual but not religious, and 43% said they were neither.[6]

How are spirituality and religion different? As one religious teacher put it, “Religion is a bridge to the spiritual, but the spiritual lies beyond religion.”[7] Some people will note that they are spiritual without being religious. Others will describe religion and spirituality, for them, as being the same thing. Of course, there is no expectation that you, as a clinician, need to be spiritual or religious, or that your spiritual and religious paths be similar to those of your patients, in order for you to be able to offer them personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care.

Ultimately, the definition of spirituality is highly individualized; each of us experiences the sacred in different ways. This is even true for people who belong to the same religion. Keeping the definitions of spirituality and religion inclusive allows for a great deal of leeway, which is essential if Whole Health care of “Spirit & Soul” is to be truly personalized to the needs of any given patient.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Aspects of Spirituality

Consider the six aspects of spirituality listed below. These are not mutually exclusive; some people may resonate with more than one of them. There may be others that you think of that are not on this list.

- Religious spirituality. Closeness and connection to the sacred as described by a specific religion. There may be a sense of closeness to a particular Higher Power. Note that the other elements of spirituality listed next are common to many different religious traditions.

- Humanistic spirituality. Closeness and connection to humankind. It may involve feelings of love, reflection, service, and altruism.

- Nature spirituality. Closeness and connection to nature or the environment, such as the wonder one feels when walking in the woods or watching a sunrise. This is an important focus for many traditional healing approaches.

- Experiential spirituality. Shaped by personal life events. It is influenced by our individual stories.

- Cosmos spirituality. Closeness and connection to the whole of creation. It can arise when one contemplates the magnificence of creation or the vastness of the universe (e.g. while looking skyward on a starry night).

- Spirituality of the mysterious. There is much that we simply cannot know or understand; perhaps it is not possible to fully grasp or know, and we must allow for the unknowable.

Which, if any, of these descriptions resonate most with you? Would it be helpful to consider these different aspects when discussing spirituality with patients? Can you think of other aspects not listed above?

Here are some thoughts about the nature of spirituality from various traditions:

Spirituality may be thought of as that which gives meaning to life and draws one into transcendence, to whatever is larger than or goes beyond the limits of the individual human lifetime. Spirituality is a broader concept than religion. Other expressions of spirituality may include prayer, meditation, being in community with others, involvement with the natural world, or relationship with a transcendent reality.[8]

Spirituality is the personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, about meaning and about the relationship with the sacred or the transcendent which may (or may not) lead to or arise from the development of religious rituals and the formation of the community.[9]

Spirituality is distinguished from all other things—humanism, values, morals, and mental health—by its connection to that which is sacred, the transcendent. The transcendent is that which is outside of the self, and yet also within the self—and in Western traditions is called God, Allah, HaShem, or Higher Power, and in Eastern traditions may be called Brahman, manifestations of Brahman, Buddha, Dao, or ultimate truth/reality. Spirituality is intimately connected to the supernatural, the mystical, and to organized religion, although it also extends beyond organized religion (and begins before it).[10]

The nomadic gatherer-hunters live in an entirely sacred world. Their spirituality reaches as far as all of their relations. They know the animals and plants that surround them and not only the ones of immediate importance. They speak with what we would call “inanimate objects,” but they can speak the same language. They know how to see beyond themselves and are not limited to the human languages that we hold so dearly. Their existence is grounded in place, they wander freely, but they are always home, welcome, and fearless.[11]

It may be that exploring the relationship between spirituality and Whole Health is more about asking questions than providing answers. Perhaps it is more about providing a context for exploration and helping people discern what they need—and whom they need—to accompany them on their paths. As Rachel Remen puts it in her book, Kitchen Table Wisdom:

I have come to suspect that life itself may be a spiritual practice. The process of daily living seems able to refine the quality of our humanity over time. There are many people whose awakening to larger realities comes through the experiences of ordinary life, through parenting, through work, through friendship, through illness, or just in some elevator somewhere. [12]

What Do Patients and Clinicians Believe?

We are not human beings having a spiritual experience, we are spiritual beings having a human experience.

—Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Patients and spirituality

According to Gallup Polls, 89% of Americans believe in God or a universal spirit.[13] Over the last 20 years, a consistent 54%-58% of respondents note that they consider religion to be “very important” to them. According to a Mayo Clinic study, 94% of all patients regard their spiritual health to be as important to them as their physical health.[14] Forty percent of elderly patients rely on faith for coping with illness.[15] The 2010 Baylor Religion Survey reported that 87% of respondents had ever prayed for other people, 79% had prayed for themselves at some point, and 26% had tried laying on of hands.[16]

Depending on the study, between 66% and 83% of patients report that they prefer to have their physicians ask them about their spiritual or religious beliefs.[17][18][19] The sicker people are, the more they seem to want their physicians to discuss spirituality. A 2001 study of a large sampling of patients found that 19% wanted spirituality and religion to be discussed in a routine office visit, 29% would want it if they were in the hospital, and 50% would want it at the end of life.[19] However, patients report they do not bring these issues up because they do not think their clinicians are prepared to address them.[20]

Clinicians and spirituality

Physicians (who are the most studied when it comes to different clinician groups and spirituality) also report a strong spiritual connection. A 2017 study found that 65% of physicians in a multispecialty referral center believe in God.[21] Forty-five percent reported praying regularly, and 21% had prayed with patients. Seventy-nine percent of family physicians identified themselves as “very” or “somewhat” strong in their spiritual beliefs.[22] A survey found that 96% of family physicians feel spiritual well-being is a factor in health.[8] In one survey, 85%-90% of physicians reported that it was important for them to be aware of their patients’ spiritual orientation.[23]

For all that they view it as important, they may not be asking about it, however. In one survey, 80% of respondents reported their physicians “rarely” or “never” discuss spiritual or religious issues.[19] Physicians report asking about spirituality only 50% of the time when end-of-life[24] issues arise.

There are several reasons why this might be the case. When asked about barriers to doing spiritual assessments, clinicians responded as follows:[25]

- 71% noted lack of time as an issue

- 59% cited lack of experience

- 31% were unsure that it was part of their role

Studies related to nonphysician clinicians and spirituality are not as easy to find. A survey of 774 trauma professionals (including nurses, physicians, and others) found that nearly 20% of them (compared to 57% of a sample of 1006 members of the general public) believed that someone in a persistent vegetative state can be saved by a miracle.[26] A majority of a sample of 5,500 British social workers acknowledged that spirituality is “a fundamental aspect of being human”[27], and many academic social workers mention the need for social work students to have more training in the area of spirituality. A 2006 study found that nurses are very skilled at identifying patients’ spiritual needs but do not necessarily have the skills and resources to respond to those needs once they identify them.[28]

Whole Health Assessment: Spirit & Soul

- Learn (and share as appropriate) about spiritual and religious beliefs.

- Assess spiritual distress or help patients draw upon their strengths.

- Provide compassionate care.

- Assist with finding inner resources for healing and acceptance.

- Determine spiritual/religious beliefs that could affect treatment choices.

- Identify whether or not someone needs a referral to a chaplain or other spiritual care provider.

Simply asking about spirituality can be an important aspect of drawing it into the personal health planning process. In fact, many who write about spirituality and health argue that, when it comes to this topic, asking questions is much more important than having answers. There is no requirement that a clinician agree with a patient’s beliefs, but it is certainly of benefit to know what those beliefs are, and how they tie in with Whole Health.

A review of 11 studies concluded that there are six key aspects of spiritual care that are most fundamental to people and should be high priorities for clinicians to discuss. These include:[30]

- What gives them meaning, purpose, and hope

- Their relationship if they have one–with God (or another Higher Power)

- Their spiritual practices and how they follow them despite their health issues

- Religious observances (celebrations, holidays, worship services, and ceremonies) they want to follow, and how they can do so despite their health concerns

- Interpersonal connections

- Interactions with health care team members

There are many ways to gather a spiritual history during a conversation with a patient, and a number of assessment tools have been created that help clinicians draw in the key aspects of spiritual care. These include an array of mnemonics, including FICA,[31] HOPE,[32] and SPIRIT,[33] which were ranked among the best of 25 different assessment scales assessed in a 2013 systematic review.[34] Choose one method, memorize it, and use it with your Veterans. Here is what some of the various mnemonics stand for:

- FICA reminds clinicians to ask about: [31][35][36]

- Faith and Belief—the things that help a person cope with stress and bring meaning to life

- Importance—how belief affects self-care

- Community—role of a spiritual community in a person’s life

- Address in Care—how the care team should address concerns

Note that the creator of this mnemonic, Dr Christina Pulchaski, strongly recommends that people receive training prior to using these questions.

- HOPE focuses on:[32]

- Hope—what provides hope

- Organized religion—is one in a community and is that helpful

- Personal spirituality/practices

- Effects on health care needs and end-of-life choices

- SPIRIT emphasizes:[33]

- Spiritual belief system

- Personal spirituality

- Integration with a spiritual community

- Rituals and restrictions spirituality requires for health care

- Implications of spirituality and religion for medical care

- Terminal events planning (end-of-life issues)

The I AM SECURE Mneumonic

One tool, which is designed to highlight key topics in the spiritual care of Veterans using the Whole Health approach, is the I AM SECURE mnemonic. It covers multiple topics, and clinicians can choose which ones are most relevant to ask at any given patient encounter; you do not have to ask them all. The topics, and questions you can ask that relate to them, are as follows:

- Impact of military service. Did experiences in the military affect your spiritual or religious beliefs? If so, how?

- Approach to your spirituality in a medical setting. How do you want members of your care team to approach this topic? Do you prefer that they bring up spirituality and religion, or not?

- Meaning in life. What gives you a sense of meaning and purpose? What really matters to you? What are your guiding principles? What do you want your health for? (This ties into the fundamental questions related to the Whole Health approach —the MAP questions.)

- Spirituality—definitions and practices. What does spirituality mean to you? What are your most important beliefs and values? If spiritual practices are a part of your life, what are those practices, and how are they linked to your health? (This can often be a useful topic when a person does not have a specific religious affiliation.)

- Ease—sources of peace. What gives you ease? What helps you through when times are hard? What gives you hope or peace of mind?

- C Do you belong to a specific faith community or religious group?

- Understanding of why this is happening. What do you believe is the cause of your health problems? Why do you think this is happening?

- Rituals, practices, and ceremonies. Are there specific activities or ceremonies you would like to have arranged during hospital stays, or any beliefs that will affect how we take care of you? (Examples might include refusing blood transfusions, eating kosher, or wanting to fast for Ramadan.)

- End of life. What are your perspectives on death? How do your beliefs affect your decisions about end-of-life issues? (A discussion of code status and advanced directives might also be relevant here.)

If you are pressed for time. If you only have time to ask one specific question about spirituality, consider the following:

What gives you your sense of meaning and purpose?

The answers may surprise you, and they add depth and richness to conversations with patients. A number of answers have been reported by various clinicians who have asked this question:

- My faith

- My community

- Connections: my family, my life partner, my children, my friends, my pets, my community

- My meditation practice

- My work

- Doing good for others: Volunteer work, donating to charities, etc.

- Travel and experiencing new places

- Creative pursuits: My music, my dancing, my writing, my photography.

This one question can often take you to the heart of why health matters to a person. It is a “way in” as you work with patients to define their personal health missions.

Using "I AM SECURE" with Eric

With Eric’s permission, you sit down with him in his hospital room and ask him a series of questions, based on some of the most relevant topics covered in the I AM SECURE mnemonic, as described in the previous section of this overview. As you will note, these questions need not be asked in a specific order. Rather, they weave into the flow of the conversation. Eric answers the questions as follows:

Meaning. Tell me about your spiritual beliefs. What gives your life meaning?

I grew up in a very religious family. We went to church every Sunday, and I enjoyed it. I was one of those kids who read the Bible out of interest, not because anyone made me. I used to pray every night before bed. Protecting others gives my life meaning. Doing good for people, whether they are people I love or people I hardly know, makes me feel like I matter. My three children and my wife matter most.

Impact of military service. It sounds like part of going into the Marines was because it tied in with your beliefs. Can you tell me more about that?

I went into the Marines proud to be a soldier. I wanted to help people. I felt it was the way I could make the most difference. Then, I killed someone. It was actually the guy who shot me in the leg. He killed one of my buddies right before I killed him. Even though it has been a few years since it happened, I still see his face almost every night when I start to fall asleep. There are so many emotions. I am so angry. I feel guilty that my buddy died and I didn’t. I can’t understand why I survived. And it’s weird—I am also mad that my leg is messed up forever and I wish it would work right. Sometimes I wonder if it is my punishment for killing the guy.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Reflect on how you would respond to what Eric just said. Some options include the following:

- Validate Eric’s feelings. “I can understand why you feel…” This is especially important, because Eric has just revealed extremely personal information. To say nothing could feel like a breach of trust to him.

- Acknowledge the difficulty. “It sounds like this has been very difficult…” It is important to recognize that Eric carries this with him every day.

- Ask how he copes with it. “What helps you handle these challenges? What gets you through the day? What else would be helpful to you?” This can help to identify and invoke a Veteran’s own beliefs/and resources for addressing these concerns. It taps into Eric’s resilience.

- Consider whether or not it is appropriate to refer him for additional mental or spiritual health support. “I am wondering, as I hear you describe this, if it would help for you to talk to someone who is very skilled with working with people in your situation…” Be careful, though, not to seem as though you are “turfing” him to someone else.

As Eric responds to other questions, consider how you could frame your responses to other statements that Eric makes.

Rituals, practices, and ceremonies. Do your beliefs influence how you take care of yourself? How?

I always believed it was important to take care of the body and the spirit, and every other part of me. I don’t smoke, and I don’t drink very much, because I honor my body. But in combat, you’re trying to destroy someone else’s body before they destroy yours, you know? I am trying to wrap my head around why God would allow that kind of thing to happen, but I can’t.

Community. Are you part of a spiritual or religious community? Is this of support to you? How?

A guy at church heard the story of what happened to my leg, and he came up to me and patted me on the back. He said it was good that I did God’s will and taught the guy who shot me a lesson. Another time, a woman from church asked me how I could bear to live with the knowledge that I had killed other people. Both times, I didn’t know what to say. Those conversations really shook me up. I have been avoiding church, because I just don’t feel very worthy of God’s love right now, and I don’t want to talk to anyone else about being in Afghanistan. They checked me out and said I am not depressed or anything, but I feel like something’s not right.

Approach to this in a medical setting. How should we draw these issues into your care? Can we explore these issues more?

I don’t know. My beliefs are fundamental to who I am, so I can’t leave them out. What do you think?

These answers are powerful. In just a few minutes, the conversation has shifted into a much deeper place. Eric’s answers suggests directions he could take as he creates a PHP. Before moving into the content of his PHP, however it is helpful to highlight what the research tells us is (or is not) likely to be helpful.

What Does the Research Tell Us About Spirituality and Health?

One should not be surprised that any effect of ritual, meditation, prayer, or potentially any other religious or spiritual practice would express itself through physical mechanisms. Religiosity/spirituality, like all of reality, is multileveled or stratified.[37]

Research may not ever fully answer all our questions in the area of spirituality and health. In fact, some argue that understanding Spirit & Soul requires the use of “other ways of knowing” such as reflection, personal experiences, intuition, ongoing personal exploration, and creating and appreciating the arts. (For more on this, refer to “How Do You Know That? Epistemology and Health.”)

That said, research does offer some important insights about the current state of the evidence regarding spiritual and religious issues and their impact on health and well-being. As you review the research findings described below, keep in mind that some of the studies lump religion and spirituality together, as “religiosity/spirituality” (R/S), despite the distinctions between the two that were noted earlier. If they focus just on one or the other, that is noted.

1. Religiosity and spirituality affect our physiology.

In this era of mapping brain activity using devices like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) machines, we have some insights about how spirituality and religiosity affect the brain at a physiological level. This area of study is sometimes called “Neurotheology.” There are also studies that test levels of various chemical compounds in the body to see if they shift when people are having spiritual and/or religious experiences. Examples of study findings include the following: [37][38][39][40]

- Prayer and meditative states activate the prefrontal structures of the brain.

- They also increase blood flow to the other parts of the brain, including the frontal cortices, cingulate gyri, and thalami.

- They decrease flow to the superior parietal cortices. When this occurs, people describe the feeling that they lose their sense of “self”; that they no longer feel like they have physical boundaries or limits.

- With prayer and meditation, the left hemisphere overall is positively affected. There is a link with this activation and immune response.

- Higher dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex correspond with a higher level of religiosity. Those with loss of dopamine (e.g. people with Parkinson’s disease) lose their religiosity and spirituality.

- The frontal lobes of the brain become more active when a person engages in pro-social behaviors like perspective taking, empathy, and forgiveness.

- People who have more R/S have thicker of cortical regions of the brain. This can be protective against depression, which is associated in many people with cortical thinning.[41]

- Affirmation of one’s values and beliefs lowers cortisol (and neuroendocrine stress) levels.

- These physiological changes happen in part because of our experiences; it is not simply that some people are born with brains that have more activity in certain area. Both “nature” and “nurture” are important.

2. Religious affiliation and spiritual practices are linked to decreased mortality.

Data from the Nurses’ Health Study (focused on over 74,000 participants over 16 years) found that mortality rate for those who attended weekly religious services was 845 deaths per 100,000 people per year, compared to 1229 for those who had never attended.[42] This represents a hazard ratio of 0.74. There seems to be a dose response, too; attending more than one service per week lowers mortality risk even more.

A meta-analysis of all available studies on spirituality and religiosity done in 2000 found a 22% lower mortality rate (odds ratio 0.78) for those who attended religious gatherings at least once weekly.[43] This study was criticized for not demonstrating that this 22% represented a “clinically significant change.” The authors responded that the impact was actually quite meaningful, noting that, statistically speaking, the benefits of religiosity and spirituality, according to their findings, were comparable to the following:

- The positive mortality benefit of treating people with a known heart disease history and who have high cholesterol with statin drugs

- The inverse of the amount of harm caused by heavy drinking (though it would be oversimplifying to say that going to church negates the health effects of heavy drinking)

- The beneficial effects of exercise-based rehabilitation following a heart attack.

Other, more recent, studies also indicate a mortality benefit for those who attend religious services. For example, in a study that followed nearly 5,300 adults for 28 years, researchers found that those who attended religious services one or more times weekly had, on average, a 23% lower mortality rate.[44] This was after correcting for age, sex, education, ethnicity, baseline health, body mass index, and even social connection, which is often cited as a key element of religious practices that contributes to health benefits.

What are some of the other study findings in this area? Some studies indicate that Orthodox Jewish people seem to be healthier than secular Jewish people. A 1986 study found that the odds ratios for first heart attacks were 4.2 for secular Jewish men and 7.3 for women compared to those who described themselves as Orthodox.[45] Similarly, a study of male Israelis found that Orthodox Jewish men had a 20% lower risk of fatal coronary heart disease compared to nonreligious Israeli men.[46] In both studies, researchers adjusted for various cardiac risk factors, such as elevated blood pressures and smoking.

Beyond attending religious services, having “a higher purpose in life” is also linked to better survival. A meta-analysis that included 10 studies with over 136,000 participants found that those with a sense of “higher purpose” had a relative risk of death or cardiovascular events of 0.83[47].

Why mortality improves is the subject of much speculation.[48] Adjustment for many other variables (eg, being religious or spiritual correlates with healthy lifestyle behaviors, strong social connections, more positive emotions, more time in a meditative state, more optimism, better socioeconomic status) does NOT explain away these benefits[49]. Controlling for all those variables, the association between spirituality/religiosity and health remains “moderately robust.”

3. Religiosity and Spirituality (R/S) also have an impact on mental health, physical conditions, coping, and healthy lifestyle behaviors.

The number of studies on R/S has grown exponentially in recent years.[50] Harold Koenig, one of the main researchers in religion, spirituality, and health, summarized the research findings based on number of favorable and unfavorable studies for different conditions from 1932-2010. In general, the overwhelming majority of studies—and particularly those with the best ratings as far as their methodology—have favorable findings. Few studies have negative findings; those that are not positive tend to find no effect.

Mental Health Issues

Most studies of religion/spirituality and health (over 80%) deal with mental health-related topics.[33] A 2011 meta-analysis focused on the use of psychotherapy tailored to religious and spiritual perspectives. Doing so resulted in “enhanced psychological outcomes.”[51] A 2007 study concluded, “The incorporation of religion and spirituality into psychotherapy should follow the desires and needs of the client.”[37]

- Well-being was found to improve in 256 out of 326 studies prior to 2010. Only 3 studies reported a negative effect[50]. R/S is associated overall with overall Quality of Life for both well and ill patients, according to a variety of measures.[48]

- Meaning and purpose were positively affected in 42 out of 45 studies, and no studies showed any negative effects.

- Hope and optimism were also related to R/S. Three-fourths of studies (prior to 2010) report that hope is enhanced, and 80% of studies showed benefits for optimism, in more religious and spiritual people. No studies showed that R/S decreased these traits.

- There were also significant associations with volunteering and altruism. 15 out of 20 of the best studies reported positive relationships and two found negative associations (both related to organ donation).

- Other traits. People scoring higher on R/S score lower on ratings of psychoticism and neuroticism and higher in extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.

- People at high risk for depression, if they report R/S is very important to them, have a 90% lower incidence.[52] A 2012 systematic review concluded that, taken in sum, there was a moderate effect size when it came to treating depression with R/S-related interventions. In a 2015 review, a similar effect was not found[53], but then a 2017 review including over 5,500 study participants concluded that a high level of personal spirituality decreases the relative risk of moderate depression by half.[54]

- Data from the NHANES-II Survey, which included over 20,000 people, found that risk of dying from suicide was 94% lower for people who went to at least 24 religious services yearly, compared to those who attended less often.[55] A 2016 review of 89 articles found that religious service attendance and having a religious affiliation does not prevent suicidal ideation, but does protect against suicide attempts.[56] The protective effect may vary based on what specific religion a person follows. A 2015 review concluded, “Preliminary evidence suggests that interventions and treatments that foster personal meaning and self-compassion in addition to reducing guilt, shame, and self-deprecation can reduce suicidal behavior among military personnel and Veterans.”[57]

- People who both pray and feel they have a secure attachment to God have less anxiety; if they feel an insecure attachment, they have more anxiety. [58] Studies of R/S and anxiety show a moderate effect size, according to a 2017 review.[59]

- Substance use disorders. In a group of over 17,000 adolescents, level of religiosity was inversely related to use of tobacco, illegal drugs, and prescription drugs, as well as to heavy drinking.[60] The success of Alcoholics Anonymous is due, to a large degree, on the way it increases participants’ spirituality.[61] Degree of R/S correlates with better drinking outcomes in alcoholics at nine months.

Physical Health Issues

R/S can prove beneficial to more “physical” symptoms as well.

- Pain. A 2008 study including 37,000 people who took the Canadian Community Health Survey found that those reporting they were religious had less chronic pain from fibromyalgia, back pain, and migraines.[62] People who reported being spiritual but who did not attend services had a higher likelihood of being in pain. Interestingly, people who reported both being spiritual and attending services were most likely to do well. Pain intensity, in general, is lower for people with more R/S.[63] One study indicated that people going through rehabilitation actually indicated that spiritual distress was a more significant contributor to their life satisfaction than the physical disabilities caused by their injuries.[64] A 2015 review pointed out that pain needs to be treated from a bio-psycho-social-spiritual framework, with spiritual care being “crucial” to pain management.[65] Accessing religious and spiritual resources is more related to decreased severity of arthritis pain, chronic pain, migraines, and acute pain. Often in these types of studies, it seems that it is not so much that the pain level is decreased as that the ability to tolerate it is improved.[66]

- Cancer. For a group 20 well-designed studies focused on cancer incidence, 12 reported improved outcomes/better risk. None reported worse outcomes.[50] One review found that R/S interventions seem to stabilize psychoneuroimmunological outcomes for breast cancer patients,[67] but other reviews do not find the relationship quite so clear-cut.[68]

- Hypertension. Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) found that people attending weekly religious services had a systolic blood pressure 1.5 mmHg lower than nonattenders.[69] People who attended services more than once a week had an average decrease of 3 mm Hg. This was after various socioeconomic factors were accounted for.

- Heart Disease. In 12 of 19 studies done before 2010, there was a significant and favorable relationship between coronary heart disease and high R/S.[50] People with lower Spiritual Orientation Inventory scores tend to have progression of coronary artery disease, whereas higher scorers have regression.[70]

- HIV. Viral load[71] and CD4 counts[72] are favorably influenced by religiosity as well.

Coping

Religiosity and spirituality have been found to help people cope with many problems, including:[10][33]

- Bereavement

- Cancer

- Chronic pain

- Dental problems

- Diabetes

- General medical illness

- Heart disease

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Lung disease

- Lupus

- Natural disasters

- Neurological disorders

- Overall stress

- Psychiatric illness

- Vision problems

- The effects of war

Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors

Religion and spirituality also influence health behaviors.[10] A 2012 systematic review showed likelihood of smoking decreases as spirituality and religiosity increase. Similarly, 16 of 21 studies rated as being of “good methodological quality” found positive associations with exercise; only 2 found negative associations. Thirteen out of 21 studies found a link between R/S and a healthy diet, and only 1 found a negative connection. Of note, religious/spiritual people tend to be at higher risk for obesity, with the exception of people who are Amish, Jewish, or Buddhists. In the 25 studies Koenig and colleagues rated in their comprehensive 2012 review, 11 reported that being overweight is associated with being more spiritual or religious, while 5 found the opposite. Forty-two of 50 good-quality studies found that safer sexual practices strongly correlated with being religious as well.

4. Prayer may have therapeutic benefit, but the literature is not definitive.

There are different types of prayer. Intercessory prayer, which involves praying for another person, has been explored in several fascinating studies, including the following:

- Byrd and colleagues found, in a coronary care unit population, that the intervention group, while not experiencing lower mortality rates if they were prayed for, needed fewer antibiotics, did not require intubation (as did many people in the control group), and were less likely to develop pulmonary edema.[73]

- A 2017 trial including 92 Muslim patients with migraines found that mean pain intensity (on a visual analog scale) decreased in the group that received propranolol and prayer versus propranolol alone.[74] The prayer group received 45 minutes of intercessory prayer weekly for 8 weeks but the study did not clarify who was doing the praying.

- In another study of 40 patients with AIDS, which controlled for age, CD4 counts, and AIDS-defining illnesses, there were several differences between the prayed-for patients and controls. [75] In the prayer group, there were fewer new AIDS-defining illnesses, illness severity was scored as lower, and there was a need for fewer (and relatively shorter) hospitalizations and doctor visits. Prayed-for patients also rated their mood more favorably.

- Sixty percent of chronic pain patients report that they use prayer to help them cope.[76] Prayer is identified in most research as a positive resource for reducing pain and enhancing psychological well-being and positive affect.[77]

While these studies have had promising results, some have not shown an effect. Further research is needed. As might be expected, methodology can be a challenge for studies of this nature.[78]

5. For some, there can be negative aspects to spirituality and religion.

For all this favorable data, it is important to remember that not everyone derives benefit from being religious or spiritual. There are studies (typically a small minority) that find negative correlations between R/S and health. While harm is quite unlikely, potential negative impacts should be borne in mind. Based on their beliefs, people may in rare circumstances do the following:

- Stop life-saving medications

- Fail to seek care

- Refuse blood transfusions

- Refuse prenatal care

- Ignore or promote child abuse or religious abuse

- Replace mental health care with religion

- Get entangled in a religious community—or cult— that has negative effects on health.

Individualizing care is vital, to ensure that any spiritual components of a PHP are truly appropriate to a given person’s belief system and comfort level. It goes without saying that a clinician should NEVER attempt to impose his or her beliefs on a patient. Proselytizing is not appropriate.[32][79]

Pathologies of the Spirit & Soul

Spiritual distress and spiritual crisis occur when individuals are unable to find sources of meaning, hope, love, peace, comfort, strength and connection in life, or when conflict occurs between their beliefs and what is happening in their life. This distress can have a detrimental effect on physical and mental health.[32]

Just as there are physical and mental illnesses, or pathologies, there are spiritual ones. Eric mentioned he has “other wounds that no one can see that hurt the most.” Many Veterans— and others—have those wounds. Spiritual pathologies are linked to poorer health outcomes (mental and physical), and addressing them is an important aspect of Whole Health care.[76]

Common spiritual problems, and examples of what a person who experiencing them might say, include the following:

- Spiritual alienation. “I feel abandoned by my Higher Power. I feel disconnected from myself, from others.”

- Spiritual anxiety. “I feel unforgivable. There is so much that I don’t know.”

- Spiritual guilt. “I deserve to be punished. I must have done something wrong, to feel this way. I am full of regret.”

- Spiritual anger. “I am angry with God. I hate the Universe. I feel betrayed.”

- Spiritual loss. “I feel empty. I do not care anymore. I am not sure what matters anymore. My sorrow is overwhelming.”

- Spiritual despair. “There is no way a Higher Power could ever care about me. I have lost my hope. Things feel meaningless.”

These pathologies can arise when a person experiences moral injury. Moral injury occurs when a person commits an act, or is unable to prevent an act, that goes against his or her deeply held moral beliefs.[80] As one expert defines it, “Moral injury is an emerging construct that attempts to more fully address the needs of military populations. This construct attempts to capture the constellation of inappropriate guilt, shame, anger, self-handicapping behaviors, relational and spiritual/existential problems, and social alienation that emerges after witnessing and/or participating in warzone events that challenge one’s basic sense of humanity.”[81] Examples might include incidents relating to death or harm to a civilian, being under friendly fire, being unable to prevent a comrade’s death or suffering, or violating rules of engagement to save a comrade.[82]

Moral injury is linked to PTSD and other mental health problems, such as depression and suicidal ideation. Other sequelae include social problems, mistrust, existential issues (eg, loss of one’s faith), feeling betrayed, and valuing oneself less.[83]

There are various therapeutic approaches that are being used to help people struggling with moral injury. One way is to explore the mismatch between a person’s meaning system (their values, principles, etc.) and the realities of a morally injurious experience (MIE). Meaning making, which involves trying to give the experience a context in terms of one’s meaning system, has shown promise.[84] Having conversations about meaning and purpose, which is fundamental to the Whole Health approach, may be helpful.

It has been noted that chaplains in the military and with the VA, in particular, who regularly engage with military personnel and Veterans are well-positioned to explore these issues.[85] They can perform assessments, support, counseling, and worship-related activities that can help. Such conversations require a clinician’s full attention.[86] It is helpful to ask for assistance from a chaplain or other professional to explore—and ease— their suffering. One person with a belief is equal to a force of ninety-nine who have only interests.

—Peter Marshall

In VA facilities, chaplain coverage is available every day, 24 hours a day. Chaplaincy services are available for all Veterans, and chaplains can prove to be invaluable as members of a patient’s Whole Health team.

Who Are Chaplains?

It can be really hard—or really easy— to explain what I do for a living. Chaplains share academic training with clergy, but we complete clinical residencies and work in health care organizations. Our affinities are with the patient and family, but we may also chair the ethics committee or serve on the institutional review board, and we spend a lot of time with staff. We must demonstrate a relationship with an established religious tradition (in my case, United Church of Christ), but we serve patients of all faiths, and of no faith, and seek to protect patients against proselytizing. We provide something that may be called “pastoral” care, “spiritual” care, or just “chaplaincy”—but even among ourselves, we do not always agree about what that thing is.[87]

During World War II, on February 3, 1943, the US ship Dorchester was torpedoed as it moved through the Atlantic toward Greenland. There were four chaplains on board, from different denominations. They helped to calm the 902 men on board after electrical power was lost. They organized an orderly retreat in lifeboats. When it became necessary, they gave up their own life jackets and were last seen singing hymns as, arm-in-arm, they went down with the ship.

Any health care provider who has worked closely with a skilled chaplain likely recognizes qualities in them that they share with the “Four Chaplains of the Dorchester.” Most chaplains seem to innately “get” what Whole Health means, and they make incredible contributions to enhancing it every day.

Modern health care chaplaincy had its origins in the 1920s with the work of Reverend Anton Boisen, who worked with patients at Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts.[88] Chaplains are individuals—often members of the clergy—who usually have received advanced training in working with people in health care settings. Board certification, while not completed by all chaplains, especially in more underserved locations, requires completion of 1,600 hours of supervised clinical pastoral education training in an accredited hospital-based program. Chaplain trainees must demonstrate competence in twenty-nine different areas.

What Do Chaplains Do?

Research in many fields indicates that chaplains’ roles are highly varied.[89] Some of their responsibilities include the following:

- When people experiencing pain, illness, or loss ask, “Why did this happen to me?” Chaplains may not have an answer for the question, but they can be present to help patients find their own answers.

- Chaplains may spend a lot of time focusing with patients on the “why,” ie questions related to meaning. For many clinicians, the task is to focus primarily on questions of “What is the medical explanation for what is happening?” or “What can be done to solve a problem?” Even when that is not the main focus, their work responsibilities may limit the time they can spend addressing suffering and spiritual needs. Chaplains can offer support as patients ask, “Why did this happen to me?”

- They can offer prayers or perform specific ceremonies or services, depending on a patient’s particular spiritual/religious background. They might lead meditation or reading of holy texts, assist with observance of holy days, anoint the sick, assist with memorial services, or facilitate holiday observances.

- Chaplains listen, and they help support decision-making and communication with other members of a person’s care team.

- They support patients’ family members.

- They offer support with end-of-life care and decision-making, including, in some locations, assisting with completion of Advance Directives.

- They address ethical concerns of staff and patients.

- They offer compassion and empathy.

- Chaplains add information about spiritual concerns and pastoral care interventions to the medical record.

- They share in positive experiences —recoveries, good news, celebrations— as well.

- They connect patients with appropriate clergy members, based on individual needs.

- Many chaplains provide all these services for health care colleagues as well as Veterans.

- In the Department of Veterans Affairs, chaplains specifically do the following:

- Ensure that all Veteran patients receive appropriate clinical pastoral care, as the Veteran requests or desires.

- Ensure that Veterans’ right to free exercise of religion is upheld. They respect Veterans’ choices about meeting with anyone providing spiritual/religious care, and if so, whom.

What Does the Research Tell Us About Involving Chaplains in Care?

Spiritual care unique to veterans includes forgiveness for war crimes or sin, working through guilt related to killing in war, reconnection to God, honor for what they have done for their country, and connection to religion through hospital chaplains because of the lack of their own churches or pastors.[90]

Providing spiritual care improves patient outcomes. That idea is intuitive for most people, and it is supported by research. Chaplains fill an important niche on a Whole Health team. Many clinicians are uncomfortable discussing spiritual issues or responding to patients’ responses on spiritual assessment tools.[91] Many clinicians do not have the time required to offer good spiritual care. Chaplains are comfortable working in these areas.

There is a need for more research related to chaplaincy, spiritual care, and patient outcomes, but there are some noteworthy study findings.

- A 2014 study of a group of primary care centers in England found that, even after controlling for numerous variables, there was a significantly positive relationship between well-being scale scores and having had a consultation with a chaplain.[91]

- A Canadian study concluded that “having a chaplain who supports the emotional and spiritual needs in the health care workplace makes good business sense” because one-third of the workers met with the chaplain at least once.[92]

- A 2017 mixed-methods study gathered data from 200 patients, as well as medical students and residents who had recently interacted with chaplains.[93] 93% of patients felt that their interactions with chaplains changed their lives in a positive way. 88% of students and 93% of residents fully agreed chaplains were useful and important members of a care team, and fewer 1% of each group disagreed, versus feeling neutral.

- A 2013 survey of VA chaplains found that chaplains most commonly saw patients in the VA for anxiety, alcohol abuse, depression, guilt, spiritual struggle with understanding loss or trauma, anger, and PTSD.[94]

- Service members and Veterans with mental health issues tend to visit clergy (as do many non-military personnel) because of familiarity, convenience, accessibility, and shared worldview. They also tend to seek them out because they want help with religious observances or would like a chaplain to serve as a confidant.[94]

- There is room for greater integration of mental health professionals and chaplaincy services.[94] There is also a need for more involvement of chaplains in interdisciplinary cancer care.[95] The VA’s Mental Health and Chaplaincy Program was created for this reason.[96]

When Should I Call a Chaplain?[97]

Here are some examples of when it might be helpful to call for a chaplaincy consult or otherwise request their services:

- A patient, family member, or care team member displays symptoms of spiritual distress, or spiritual pathologies, including the following:[98]

- Expressing a lack of meaning and purpose, peace, love, self-forgiveness, courage, hope, or serenity

- Feeling intense anger or guilt

- Displaying poor coping strategies

- Struggling with moral injury, as described earlier.[94]

- Someone requires additional assistance exploring the meaning of what is happening to them

- Someone needs support with coping with the illness or death of a loved one.

- Ethical uncertainties or moral dilemmas have arisen around someone’s care.

- A patient (or family member, with the patient’s permission) wants to connect with clergy from their religion or wants have a particular ceremony, rite, or holiday observance performed.

Additional Resources

To learn more about chaplains, refer to the following:

- VHA National Chaplain Center

- It has resources for both Veterans and clinicians. This site features national lists of VA chaplains, both by name and by location.

- Chaplains as Comforters and Counselors

- New York Times Article describes the varied roles chaplains fill in the Westchester Medical Center.

- VA Chaplain Services

- Avideo that explains a chaplain’s role to patients.

- Feldstein, BD. Bridging with the Sacred: Reflections of an MD Chaplain. J Pain Symptom Management. 2011;42(1):155-61.

Developing Your Own Spirit & Soul Skills

It is clear that Eric, our patient, has a number of spiritual concerns, and these are perhaps the highest priorities for his ongoing care, especially now that his acute physical issue—his pneumonia —is resolving. He completed a spiritual assessment, based on the IAMSECURE mnemonic, and it is clear he feels disconnected from his religious community. He has certainly been subjected to moral injury related to losing his friend and killing the enemy who killed his friend and shot him. Eric is struggling with guilt and loss. His spiritual life seems less rich for him, and it is likely he is experiencing some spiritual despair, including a sense of unworthiness. What are Eric’s next steps? How can you be most helpful to him? How might his Whole Health team support him? In addition to having Eric speak to a chaplain, which would be a high priority, some of the following tools and guidelines might also prove useful:

1. Know yourself. What do you believe?

A physician needs to understand his or her own spiritual beliefs, values and biases in order to remain patient centered and nonjudgmental when dealing with the spiritual concerns of patients. This is especially true when the beliefs of the patient differ from those of the physician.[32]

First and foremost, it is vital that you, as a clinician, have a strong sense of your own spiritual beliefs and struggles as you approach the care of Eric and others like him. If you want to focus on “Spirit & Soul” as an essential part of your patients’’ self-care, you will inevitably encounter situations where knowing your own perspectives will be vital. For example, with Eric, it helps if you have a sense of the following:

- What your personal faith, tradition, beliefs, and practices are (or are not)

- Whether or not you believe in a Higher Power

- What you think about prayer

- Your perspectives on sin and punishment

- How you relate to guilt yourself

- Your comfort with the concept of forgiveness and your view of its relevance to medical settings

- Your comfort with discussing these topics with others (which will increase as you give greater attention to all these areas).

Refer to “Assessing Your Beliefs about Whole Health” for additional guidance with exploring these issues. To explore working more effectively with clashes between your beliefs and those of others, refer to, “How Do You Know That? Epistemology and Health.”

2. Know about coping.

In a 2006 essay on spiritual growth and illness, Tu describes three stages that people experience during the coping process:

The first stage occurs during an acute, serious illness and characterizes the patient and family as withdrawn, shocked, passive, compliant, and unquestioningly dependent on the care-providers. The second stage is one of struggle, and is characterized by refusing to take pills and trying to regain control, in addition, to re-examining the cause of the illness so as to prevent its recurrence. Finally, the third stage, which does not always occur, may depend on the patient’s and family’s life experiences and on the seriousness of the illness. The third stage of the coping process involves a far-reaching assessment into the meaning of suffering and life. Thus, the third stage is regarded as the spiritual stage, which originates from inner self-reflection and the reorganization of one’s value system with respect to existence in the universe. Because of this, growth may change and enrich a patient’s life after illness…[99]

Many patients are most in need of additional support when they are at Stage 2 and potentially moving into Stage 3. This is the case for Eric, and it is the case for many people going through some form of loss. As Tu goes on to elaborate,

However, growth in spirituality is not limited to illness or death. Any severe loss in life may lead to the reordering of one’s value system, such as the loss associated with physical disability, bereavement, or bankruptcy. Moreover, any severe disappointment or maladjustment may also provide an opportunity for spiritual growth. In the face of the threat of death, the fear and anxiety of “becoming nothing” tend to pool all the patient’s past, present, and future anger and pain together, resulting in an even stronger motivation for a spiritual solution.[99]

What you, as a clinician, can do to help someone move through these stages will vary based on your personal beliefs, training, scope of practice, and comfort level. Of course, it will also vary based on the unique needs of any given patient. Exploring options is much less daunting if you remember that it is a collaborative process. The patient’s entire team ideally will participate, and the patient is the captain of that team.

Keep asking what you can do to help, in whatever your role is. Van Leeuwen and Cusveller, suggest that nurses can do much to help people meet needs such as performing everyday spiritual rituals (e.g. giving them opportunity to pray, honoring diet requests, helping them with Sabbath observations).[100] Similarly, all the members of a Veteran’s team can help to console anyone who is experiencing general stress. When true spiritual distress arises, though, it is important to involve others with additional expertise. These others will most likely be chaplains (there is an extensive chaplaincy network within the VA system). Clergy, spiritual directors, shamans, medicine men and women, or others may also play a role, depending on the patient’s background and preferences.

3. Listen

An important aspect of working with “Spirit & Soul” is asking the right questions. Spiritual care is about recognizing and responding to the “multifaceted expressions of spirituality” we as clinicians encounter.[101] Simply listening, with compassionate and nonjudgmental presence, promotes Whole Health. Refer to “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part II: The Power of Your Therapeutic Presence” for more on this important topic.

4. Discuss forgiveness, when appropriate

Refer to “Forgiveness: The Gift We Give Ourselves” for more information. Studies indicate that people who are more inclined to forgive have lower blood pressure, muscle tension, and heart rate and fewer overall chronic conditions.[102][103] Of course, how forgiveness fits into a Veteran’s perspective will determine whether or not a clinician raises the topic. Forgiveness is given different emphasis in different spiritual and religious traditions.

5. Encourage a Veteran to start a spiritual practice of his/her choice

What starting a spiritual practice looks like will vary from person to person. Some people may choose to join a particular spiritual group or community, be it a church, a scripture study group, or even a 12-step program. Others may wish to find a teacher who will work with them individually, or they may choose a solo practice, such as praying or meditating quietly on their own on a regular basis. It may be helpful for you to briefly describe a variety of spiritual practices that others find helpful. Regularly spending time in nature can be a useful spiritual practice, as can various creative pursuits. Some people gravitate toward doing a regular loving-kindness meditation. Trust that patients will have insights into what works best if you help them explore their options.

6. Work with spiritual anchors

At the end of the Healer’s Art medical student course, participants are given a small object, such as a palm-sized stuffed heart, to carry with them in their white coat pockets. This heart is their anchor, a reminder to them of their purpose in going into medicine, of their truest nature. To learn more, refer to “Whole Health Tool: Spiritual Anchors” in Chapter 11 of the Passport to Whole Health.

7. Broaden your familiarity with other belief systems

Doing so can be useful in terms of offering care that displays cultural humility as well. A useful online guide entitled “Religious Diversity: Practical Points for Health Care Providers” can be found at the Penn Medicine website.

8. Avoid pitfalls along the way

Take care not to proselytize. It is not helpful to try to impose your perspectives on others. Do not try to resolve unanswerable questions. And do not say any of the following, if at all possible:[104]

- “It could be worse.”

- “We are all out of options.”

- “It’s God’s will.”

- “I understand how you feel.”

- “We all die.”

Back to Eric

Eric had two additional important visitors before he left the hospital. One was the pastor of his church, with whom he agreed to visit. The other was the VA hospital chaplain, who spent a few hours sitting with Eric and discussing his concerns in greater depth.

No one, at any point, told Eric that what he was experiencing was “wrong.” On the contrary, he was encouraged to voice his concerns and talk about what happened in Afghanistan that had led to his spiritual distress. Topics such as moral injury and ways to work with pain and suffering were raised.

When you see Eric on his day of discharge, he informs you that he plans to meet with a psychologist who is comfortable with offering counseling that welcomes Eric’s spiritual perspectives. He also has agreed—tentatively—to explore doing some work in the area of forgiveness. He understands that forgiveness is first and foremost about freeing himself from what happened in the past, and he never wants to stop honoring the memory of his combat buddy who died at the same time Eric was shot.

Eric tells you that he made an agreement with the chaplain, as part of his PHP, to take 10 minutes every day to pray, or—if praying just doesn’t come—to quietly reflect or read scripture. He isn’t ready to go back to church, but he is hoping that eventually the time will come. He also agrees to carry a photo of his wife and children with him as a spiritual anchor, a reminder of what really matters.

As you say good-bye to Eric at the end of rounds, he says, as he shakes your hand, “Thanks for taking the extra time to help me. I feel a little better, and I don’t just mean my lungs. We’ll see how it goes.” His wife, Julie, nods encouragingly and thanks you too.

Whole Health Tools

Author(s)

“Spirit and Soul” was written by Adam Rindfleisch, MD (2014, updated 2018)