The secret of the care of the patient is caring for oneself while caring for the patient.[1]

–Lucy Candib

Key Points:

- Burnout includes 3 general categories of symptoms: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of low personal accomplishment.

- Burnout rates are well over 40% in most clinician groups, including providers, nurses, mental health professionals, and social workers. In some groups, the rate is over 80%.

- Burnout can be caused by the very qualities that help you handle the challenges of being a clinician. Self-deprivation, wanting to seem in control emotionally, and wanting to seem in control of outcomes can all contribute to burnout. External factors, such as workload, colleague relationships, and level of autonomy, can also contribute.

- Burnout can have multiple negative effects on physical and mental health, as well as on work performance and patient outcomes.

- Burnout can be prevented or reversed through cultivating resilience. All aspects of the Circle of Health can help with that, including reflection on values, self-care, seeking professional care, and mobilizing resources both inside and out of the workplace.

Introduction

In 2008, the “Triple Aim of Health Care” was described by Don Berwick, former Administrator of Medicare and Medicaid Services, and his colleagues.[2] The 3 aims are: (1) improving the experience of care, (2) enhancing the health of populations, and (3) reducing care costs. While these 3 areas are important, it has been argued that a fundamentally important aim is left out: the well-being of health care professionals. Clinician well-being has now been added in to create the “Quadruple Aim,” and increasing numbers of researchers, health care leaders, and clinicians have been asking how to make it more of a reality.[3]

When your self-care as a clinician falls by the wayside—when life becomes imbalanced, work demands become unmanageable, or your stress isn’t addressed—you are at increased risk for burnout. Burnout is devastating to personal relationships, wellness, and ability to provide quality care. This Whole Health tool reviews common questions about burnout, including what it is, its causes, and who experiences it. Perhaps most importantly, it discusses ways to prevent and heal it by cultivating resilience and engagement through mindful awareness, self-care, interpersonal connections, and organizational change.

WHAT IS BURNOUT?

The term “burnout” was first used in the 1970s by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger. He defined it as “a state of mental exhaustion caused by one’s professional life.”[4] Christina Maslach, who created the widely-used Maslach Burnout Inventory, defines it as “erosion of the soul caused by deterioration of one’s values, dignity, and spirit.”[5]

Burnout symptoms do not just come and go; they remain for a prolonged period of time (weeks to months). There are 3 general categories of symptoms tied to burnout.[6]

- Emotional exhaustion

People who are burnt out have limited emotional resources to bring into encounters with others. They feel overextended, overworked, and numbed to situations that normally would have led them to feel empathy or compassion. - Depersonalization

Those suffering from burnout treat colleagues and patients as objects rather than as human beings. They are often cynical and detached. Perspectives change for burnt out clinicians. Jones, the delightful man in the Emergency Department who has 23 grandchildren, just celebrated his 60th anniversary, and whose goal is to visit the Vietnam Memorial in DC, is diminished to being known as “the belly pain in bed 12.” - A sense of low personal accomplishment

People with burnout feel their work does not make a meaningful difference. They feel ineffective and have negative feelings about themselves. Burnt out clinicians are unable to appreciate what they do for their patients and others in their lives.

WHO EXPERIENCES BURNOUT?

Anyone can experience burnout, but it is most likely to occur in people whose professions focus on helping or caring for others.[6] Burnout is closely related to “compassion fatigue,” a term coined by Joinson in 1992 to describe nurses’ experience of “secondary victimization” as they absorb the stress and trauma of their patients.[7]

The following are burnout statistics for different groups of clinicians:

- The 2018 Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report, which surveyed over 15,000 physicians from 29 different specialties found that, depending on specialty, 40-61% of respondents were burnt out.[8] This increased from an average of 40% when the survey was first done in 2013.

- Women physicians are 1.6 times more likely to report burnout than men.[9]

- Burnout begins early in training; 53% of medical students surveyed at 7 medical schools reported symptoms of burnout.[10]

- Residents and fellows have some of the highest burnout rates, with up to 80% of residents in some specialties reporting burnout.[11]

- In a study of over 7,900 surgeons, 40% reported burnout. [12] 32% reported high levels of exhaustion, 26% had high levels of depersonalization, and 13% had a low sense of personal accomplishment. 30% screened positive for depression, and 6.4% had suicidal ideation.

- It may be that nurses suffer more stress and burnout than any other professional group.[13] Well over 40% of nurses report burnout symptoms.[14] Only two-thirds of staff nurses in hospitals and two-fifths in nursing homes report satisfaction with their work.[15] A sampling of 9959 oncology nurses reported that 30% experienced emotional exhaustion, 15% depersonalization, and 35% a sense of low person accomplishment. [16]For a group of 1,110 primary care nurses those rates were 28%, 15%, and 31%. [17]

- As many as 60% of psychologists also struggle with burnout.[14] A 2018 review of 40 studies concluded that over half of all psychotherapists experience moderate to high levels of burnout. [18]

- A 2005 study of 751 practicing social workers found a current burnout rate of 39% and a lifetime rate of 75%.[19]

WHAT CAUSES BURNOUT?

Many variables contribute to burnout and for any given individual, the combination of contributing factors is likely to be unique. It seems that the very traits that make you a good clinician—dedication, responsibility, motivation, conscientiousness, and attention to detail—also increase your vulnerability to burnout. For example:[20]

- The desire to offer service can lead to a certain degree of self-deprivation. This can lead to compassion fatigue (emotional exhaustion) and to a sense of entitlement.

- The constant sense of wanting to offer excellent care can lead to an obsession with appearing invincible. Perfectionism allows no room for mistakes, and many clinicians do not deal with errors in a healthy way, especially if there is nowhere they feel they can safely discuss them.

- The intention to be competent and reassuring can lead to a sense that a clinician should have more control over outcomes than is actually the case. Metrics and quality measures may leave clinicians with the sense that they must always take action and do so successfully.

- Compassion can foster isolation. Regularly witnessing suffering can lead to emotional dissociation if you are not able to cope effectively.

In addition to common caregiver traits, other factors are also linked to burnout.[21][22][23] These can be classed as external or internal in nature.

External causes leading to burnout

- Larger patient panels

- Higher productivity requirements

- Decreasing resources

- The overall culture of medicine and nonalignment of organizational and individual values

- Lack of autonomy, flexibility, or control

- A sense of providing poor care

- Lack of fulfillment in one’s work life

- Encountering too many difficult people, including patients, colleagues, supervisors, or staff

- Problems with balancing professional life with other parts of one’s life (work-life “blend”)

- Excessive administrative and bureaucratic tasks

- New expectations and demands

- Hostile workplace, including challenges that arise due to gender, race, or age

- Malpractice suits

Internal factors leading to burnout

- Specific character/personality traits, such as:[24]

- Low “hardiness” (limited involvement in daily events, sense of no control over events, and unwillingness to change)

- Diminished external locus of control (feeling as though chance or other people have more power to bring about change than oneself)

- Tendency to be time-pressured, competitive, hostile, and controlling by nature

- Perfectionism

- Unrealistic expectations about patient outcomes

- Passive coping styles. That is, you tend to withdraw when challenges arise, versus invest the energy needed to confront them.

- Lack of a sense of meaning[25]

- A mentality of delayed gratification. That is, you have a sense of needing to put off your own needs until something else happens. (“I’ll change after I finish my medical training,” or “I’ll take more vacations once I have built up my patient panel.”)

- Guilt and an exaggerated sense of personal responsibility

Various studies show a mix of external and internal factors affecting burnout in different groups. For example, nurses who reported working in a “good work environment” had lower burnout ratings and higher patient satisfaction scores.[26] For social workers, some of the variables that correlated most strongly with the presence of burnout were number of hours worked, vacation days (or lack of them), material resources, co-worker support, percentage of stressful clients, ethical compromises, need for approval, perfectionism, and difficulty asking for help.[27] For unclear reasons, it seems that those from racial minorities tend to have lower burnout rates.[12]

Mindful Awareness Moment

WHICH BURNOUT FACTORS AFFECT YOU?

Take a moment to review the lists of external and internal factors that lead to burnout.

- Which ones are present in your life?

- How might you make changes to reduce how much these factors can influence you?

Consider asking someone who knows you well for an honest opinion about how much you have the personality traits listed above that can lead to burnout. What do you think of their assessment?

Try not to make judgments about what you discover. Learn from this exercise, rather than criticizing yourself.

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF BURNOUT?

Burnout has many negative consequences, including the following[12][14][28][29]:

- Marital and family discord[30]

- Medical errors and adverse patient events. For example, in an American College of Surgeons survey, 9% of respondents reported making a major medical error in the past 3 months, and there was a strong link between all domains of burnout and reporting a perceived error.[31] A survey of 6586 US physicians found that 77.6% of burnt out physicians reported making errors versus 51.5% of those without burnout. [32]

- Decreased patient satisfaction. A 2017 study of 63 staff and 163 patients in an academic hospital Emergency Department found that staff with higher burnout rates had poorer satisfaction ratings.[33] This was largely due to poor communication.

- Poorer decision-making in general

- Accidents

- Decreased attention and concentration

- Less empathy

- Personal health problems, including:[14]

- Early retirement

- Difficult co-worker relationships

- High job turnover

- Decreased productivity[34]

Clearly, burnout is a significant problem with far-reaching effects, both on clinicians and the quality of their patient care. What is most important is to focus on ways to prevent or reduce it.

HOW CAN BURNOUT BE PREVENTED OR REVERSED?

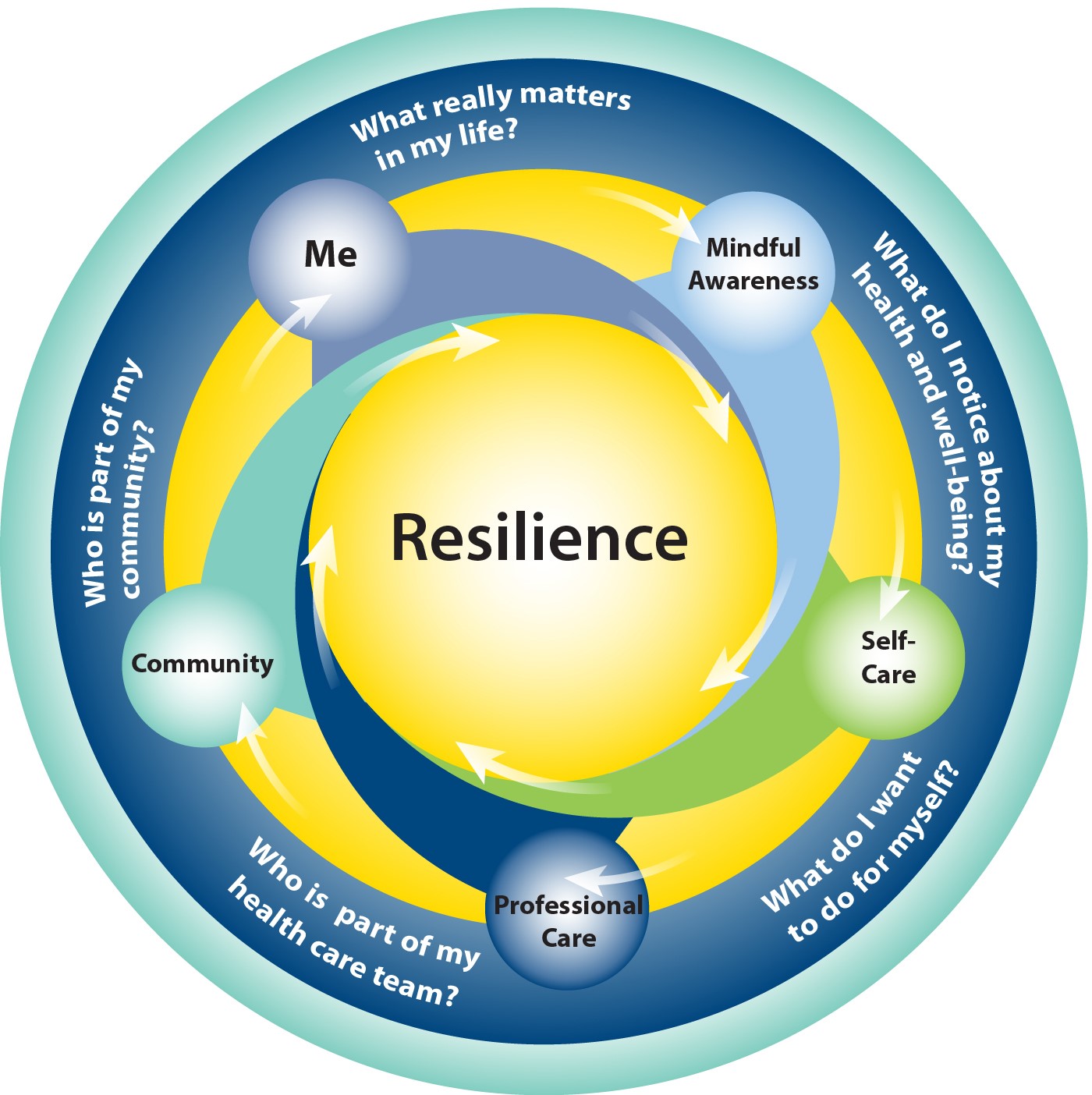

Burnout is the shadow side of resilience. Resilience is defined as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress.”[35] Fostering resilience is central to the Whole Health approach, and it can be cultivated in a number of ways. A model for resilience can be drawn from the Circle of Health, as illustrated in Figure 1, below:

Figure 1. The Circle of Resilience.

Resilience arises through a combination of the following:[36][37]

- Being clear on what you need and value both personally and professionally (Me at the Center of the Circle)

- Cultivating insight (working with Mindful Awareness)

- Taking care of yourself (the 8 circles of Proactive Self-Care)

- Receiving support of others—at both the local and organizational level (Professional Care and Community)

Each of these points merits a closer look.

HOW CAN KNOWING WHAT REALLY MATTERS TO YOU FOSTER RESILIENCE?

While each person will find unique ways to foster resilience, certain general guidelines are relevant to everyone.[38] Reflection about personal values is one of these; finding meaning in our work has been described as “the prescription for preventing burnout.”[39] For example, burnout risk is decreased for clinicians who can spend at least 20% of their time focused on what really matters to them in their work.[34] Being able to find meaning—to know what one values in work and life—can also contribute to personal and professional vitality.[40] Take some time to pause and consider what you value most highly in your work and in your life in general. What really matters to you? For more on elaborating on your values, refer to “Values.”

One value that stands out when it comes to building resilience is autonomy. A study of over 420,000 people in 63 countries concluded that individualism was linked to well-being much more strongly than wealth.[41] That is, having control over what happens to you at work is a more important value to most people than how much money they make.

As a clinician, you will be much better off if you have control of work hours, patient visit lengths, and the number of patients you are expected to see daily. You will also be more likely to thrive if you have a voice in changes at the institutional level.[42] Therefore, it may be worth it to think about the relative value of time versus money; one option is to live more frugally in exchange for more freedom to spend time the way you would like.[20]

Balance between work and other aspects of life is an additional value that is closely linked to clinician well-being.[43][44] It may help to identify the conflicts that exist between professional and personal values and rank them in order of importance.[38] It is important to allow for healthy boundaries between work and other aspects of your life for many reasons. Refer to “Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources” for more information.

HOW ARE MINDFUL AWARENESS AND RESILIENCE CONNECTED?

Mindful awareness can help to enhance clinician well-being in a variety of ways. [45]This has been noted in several recent studies.

A 2017 systematic review noted that 9 of 14 studies involving 833 clinicians found positive changes from brief mindfulness interventions (<4 hour in length) on burnout symptoms, as well as resilience, stress, and anxiety. [46] This is especially remarkable in that most mindfulness studies focus on the effects of a full 8-week training, not such short training sessions.

In 2009, Krasner and colleagues evaluated the impact of a course on mindful communication offered to a group of 70 primary care physicians in the Rochester, New York area.[47] The course had an 8-week intensive phase and a 10-month maintenance phase. Not only did participants demonstrate improvements in mindfulness scores, they also showed significant improvement in terms of scores in the three main aspects of burnout. Improvements in burnout, mood disturbance, emotional stability, and empathy scores correlated with the degree of improvement subjects showed on measures of mindful awareness. Interestingly, mindfulness scores showed the largest effect sizes at 15 months. In other words, the benefits of mindfulness practice were not only maintained, but actually became more pronounced over time. For more on mindful awareness and specific meditation techniques, refer to “Mindful Awareness” and “Power of the Mind” and their related Whole Health tools.

Fortney and colleagues found that an abbreviated mindfulness course for 30 primary care clinicians resulted in improvements in all Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales, even at 9 months follow-up.[48] There were also statistically significant improvements in measures of depression, anxiety, and stress.

A study of 93 health care providers from different backgrounds, including nurses, social workers, and psychologists, found that all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory showed improvement for participants after they took an 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course.[6]

A Mayo study focused on a 9-month program for which 74 internists attended 19 biweekly group sessions.[49] The hour-long sessions were protected time (not added on to other work responsibilities) and focused on meaning in work, clinician depression, job satisfaction, and burnout. Even 12 months after the study, meaning and engagement in work remained improved, and depersonalization was still reduced.

A small study of 38 internal medicine residents found that the 11 residents who did not meet criteria for burnout were more likely to have dispositional mindfulness (use mindful awareness at baseline) than their peers. [50]

Mindful Awareness Moment

AN EXERCISE FOR THE END OF THE DAY

As you make your way home from work, take a few minutes to reflect on the following questions:

- What did I learn today? Is there anything I will do differently based on what I learned?

- What am I grateful for today? Think of 3 positive things that you could share with another person. (Doing this can actually change the way you look at the day, as you start anticipating doing this activity and begin mindfully watching for positive experiences.)

- After my workday, what do I need right now to best care for myself? What is one way I can spend 5 minutes on my arrival home to meet that need.

We must remember that it is our inner world that keeps us grounded. By taking a few simple steps to enhance our self-awareness, we can gain new insight about ourselves and our work and renewed enthusiasm for the practice of medicine.[51]

–C. Carolyn Thiedke

HOW DOES RESILIENCE TIE IN WITH SELF-CARE?

“Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life” encourages readers to do some self-evaluation. If you haven’t already done so, take time to create your own Personal Health Plan (PHP).

In a 2012 study by Shanafelt and colleagues, 7,200 surgeons were evaluated. They found that the ones who were least likely to be burnt out had more strongly positive answers to the following questions:[42]

- I find meaning in my work.

- I protect time away from work for my spouse, family, and friends.

- I focus on what is most important to me in life.

- I try to take a positive outlook on things.

- I take vacations.

- I participate in recreation, hobbies, and exercise.

- I talk with family, a significant other, or friends about how I am feeling.

- I have developed an approach/ philosophy for dealing with patients’ suffering and death.

- I incorporate a life philosophy stressing balance in my personal and professional life.

- I look forward to retirement.

- I discuss stressful aspects of work with colleagues.

- I nurture the religious/spiritual aspects of myself.

- I am involved in non-patient care activities (e.g. research, education, administration).

- I engage in contemplative practices or other mindfulness activities such as meditation, narrative medicine, or appreciative inquiry, etc.

- I engage in reflective writing or other journaling techniques.

- I have regular meetings with a psychologist/ psychiatrist to discuss stress.

Other suggestions can be found throughout the literature. For example, surgeons have been better at preventing or healing burnout if they nurture personal relationships, participate in research, do continuing education, and/or cultivate spiritual practice.[12] Programs that supported their employees with cultivation of resilience through cognitive behavioral training, counseling, communication skill building, social support, relaxation training, music therapy, and other such measures were able to decrease levels of emotional exhaustion.[6] Working with a health coach also may be beneficial.[40]

However, treating burnout exclusively as something that people are responsible for preventing themselves has its pitfalls. It is common to hear a cynical comment such as, “They just want me to be less burnt out so they won’t have to replace me and I can see more patients for them.” As Shanafelt, put it,

“Mistakenly, most hospitals, medical centers, and practice groups operate under the framework that burnout and professional satisfaction are solely the responsibility of the individual physician….Casting the issue as a personal problem can also lead individual physicians to pursue solutions that are personally beneficially but detrimental to the organization and society, such as reducing professional work effort…” [52]

While this statement is about physicians, it holds true for other clinicians as well. Self-care is important, but organizational initiatives to decrease burnout and foster resilience may be a better place for leaders to focus their efforts.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF PROFESSIONAL CARE WHEN IT COMES TO RESILIENCE AND ENGAGEMENT?

In the shelter of each other, we live.

—Anonymous

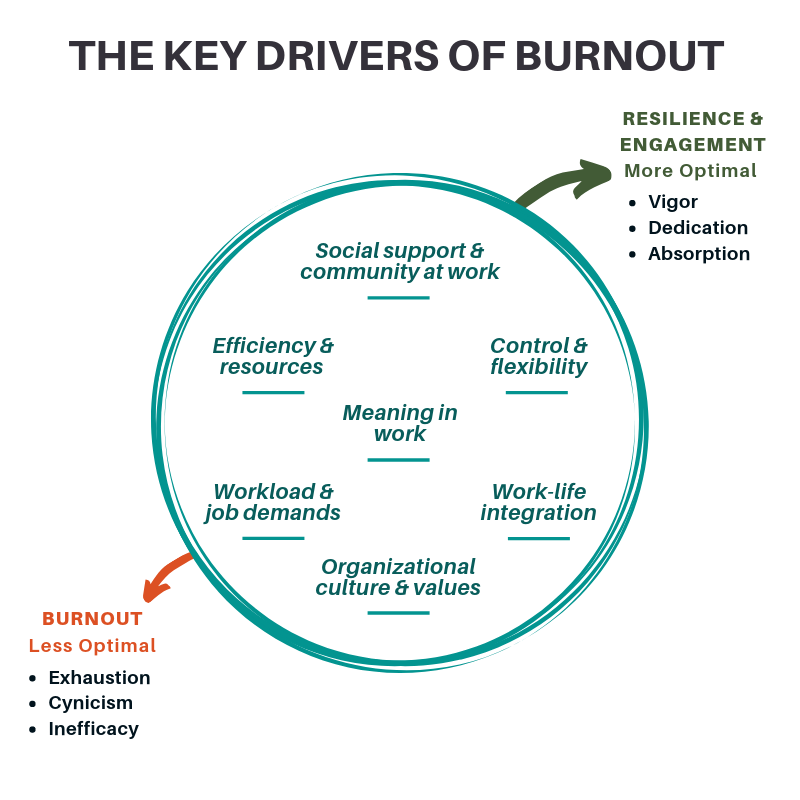

Like resilience, engagement has been described as the antithesis of burnout.[52][53] Engaged clinicians are dedicated, enthusiastic, and absorbed in their work.[54] A 2010 survey of 1,482 family physicians found that healthy relationships are much stronger predictors of job satisfaction than are staff support, job control, income, or even time pressure.[41] Some of the most successful health care teams are those that are focused on a shared mission and support each other in accomplishing it. Organizations with such teams seem to thrive even when resources and leadership support are scarce.[55]

Resilience and engagement are even more likely if there is a high level of institutional support. In fact, a 2017 systematic review of 19 studies that included 1,550 physicians noted “…burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals.”[56] This was based on findings indicating that burnout scores improved most when organizations made concerted efforts to initiate burnout prevention (and resilience and engagement enhancement).[56]

Organizational approaches to reducing burnout and fostering resilience and engagement can take many forms.[52] In a 2017 article, 9 research-informed organizational strategies were outlined.[52]

- Acknowledge and assess the problem. Gather data about burnout, publicize results, and be clear it is an organizational priority.

- Harness the power of leadership. A 2013 Mayo study found that every 1-point increase on a 60-point leadership score for a physician’s direct supervisor was linked to a 3.3% decrease in burnout likelihood.[57]

- Develop and implement targeted interventions. This should vary based on specialty, work units, and teams since causes and potential solutions are local. Shanafelt and Noseworthy offer a stepwise process that can guide leadership with this strategy.[52]

- Cultivate community at work. Gatherings, staff rooms, and protected time for clinicians to meet can prove beneficial.

- Use rewards and incentives wisely. We know that compensation based on productivity increases burnout for physicians.[58]

- Align values and strengthen cultures. Staff surveys and honest self-appraisals can help.

- Promote flexibility and work-life integration. Refer to “Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources” for more information. Being able to adjust work hours and having greater flexibility around start and end times for “shifts” can be helpful.

- Provide resources to promote resilience and self-care. As noted previously, this should be done in the context of organizational change, not instead of organizational change.

- Facilitate and fund Organizational Science. Organizational Science is the study of how different factors influence effectiveness, health, and well-being at the individual and organizational levels. Organizations can improve if they focus in on this area. Study your site, and share what you learn with other organizations, teams, and VA facilities.

The Healthy Workplace Study focused on 135 physicians and their ratings of burnout over 12-18 months after a series of workplace interventions. [59] Results indicate that burnout could be lessened through concerted efforts to improve communication and workflow, initiating quality improvement projects, and tailoring organizational improvements to clinician concerns.

Krasner et al. reviewed the organizational efforts of a primary care group in Portland, Oregon. With the support of institutional leadership, the organization enacted systems-level changes that provided physicians greater control over hours and procedures, improved efficiency and teamwork in practices, and provided meaning by integrating improvements in patients’ experience of care into administrative meetings. This program showed improvements in practitioners’ emotional exhaustion sub-scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.[47]

Arnetz and Christensen, who developed the Portland-based program with their colleagues, created interventions based on 3 “Core Principles,”[25] that included the following:

- Control. Group meetings were held to elicit physician concerns. Workflow was customized to meet clinician goals. Work schedules were flexible, and templates were customized to individual needs. Specific interests, such as preferences to focus more time on teaching, research, and inpatient versus outpatient care, were accommodated.

- Order. Office design focused on making flow as efficient as possible, and having high-quality staff was made a priority. Care management was given more of a role, and the group began using hospitalists and an Electronic Medical Record (EMR). They also adopted the Institute for Healthcare Improvement “Idealized Design of Clinical Office Practice.”[60]

- Meaning. Interventions were also done with the intent of enhancing satisfaction with offering care. Clinical site meetings gave clinical issues precedence over administrative issues. Intentional pauses were offered to grieve the loss of deceased patients. Group meetings began with patient presentations.

Health care professionals tend to be mavericks; many are fiercely independent (perhaps even a bit controlling?), and many derive a strong sense of purpose from being needed by others.[61] This can be a strength, and it can also be a challenge if we forget that we as clinicians need support too. Combatting burnout and boosting resilience are more likely if they are backed by organizational support. The Whole Health approach is best provided within a Whole Health System, where multiple providers collaborate across disciplines, with strong support from colleagues and from the organization as a whole. [62]

Approaches to organization-level work with burnout, resilience, and engagement are summarized in Figure 2, which is based on an original graphic by Shanafelt and colleagues. [52]

Conclusion

As you focus on Whole Health, continually “return full circle” to ask about how you are doing when it comes to burnout, resilience, and engagement. Start with your own practice, but dream big. How can you encourage change at the team, clinic, or facility level? The more you can cultivate resilience and decrease your risk of burnout, the better you will be able to take care of your patients as well as yourself. For more information on specific ways to foster resilience, refer to “Personal Development” and related Whole Health tools.

Author

“Burnout and Resilience, FAQ’s” was written by J. Adam Rindfleisch, MPhil, MD, (2014, updated 2017).