Personal Development

Personal Development is one of the areas of self-care in the Circle of Health and involves all the things a person can do to grow in some fashion. Examples of personal development topics that can be incorporated into Whole Health Personal Health Plans (PHPs) include building hope and optimism, finding balance in life, trying new creative pursuits and skills, volunteering, practicing gratitude, building social capital, lifelong learning, improving financial health, and building humor. Cultivating resilience is fundamentally important to personal development as well. This overview builds on the material featured in Chapter 7 of the Passport to Whole Health.

Key Points

- Personal development has many facets. Work with Veterans to decide which one they would like to focus on first. Be sure to tie their choices in with their values and what really matters to them.

- Various aspects of personal development are beneficial to health. For example, quality of work life contributes to better health, as does volunteering. Resilience counteracts burnout and is protective in many other ways. People who are more hopeful and optimistic live longer. Employment and financial health are important determinants of well-being too.

- This overview discusses 16 potential personal development topics. Keep asking yourself about how each of them could be incorporated into a PHP, when appropriate.

Meet the Veteran

Sarah is a 42-year-old Navy Veteran who now works in health care as a certified nursing assistant (CNA). She comes in to see her primary care clinician for her yearly exam. She is divorced and has a 14-year-old son and a 12-year-old daughter at home.

Sarah reports some fatigue and difficulty sleeping. Her main sources of stress are managing her household, raising her children as a single mother, working part-time at a local hospital, and never seeming to have enough time or money to accomplish her goals. She receives minimal child support from her ex-husband, who is only marginally involved in the children’s lives. She does have a few good friends, and her parents live nearby and help her with the children. She is struggling with work-life balance and finding time for herself.

She currently experiences distress and anger about her ex-husband and his family’s lack of involvement with and support for their children. She worries about having enough money to provide for her family to the point where the worries interfere with her ability to enjoy her time with them. Financial health is a concern, because she tends to overspend when she is stressed and has high balances on her credit card that she wants to pay down.

Sarah was asked to complete a Personal Health Inventory (PHI) prior to her next visit. As she worked through the PHI, it became apparent that she had few ways to manage stressors besides shopping and social support from friends and family. She notes that she needs to make her well-being a higher priority and develop additional strategies for finding balance in her life. In the past, she used to enjoy her own hobbies, such as creative scrapbooking and drawing, and she misses doing these activities. She rarely has time to exercise and reports she gets most of her movement at work on the hospital floor.

Introduction

Personal development is a broad term. It encompasses many activities:

- Improving awareness and identity

- Developing talents and potential

- Building social capital

- Nurturing positive emotions

- Fostering lifelong learning

- Enhancing creativity

- Improving quality of life

- Contributing to the realization of dreams and aspirations

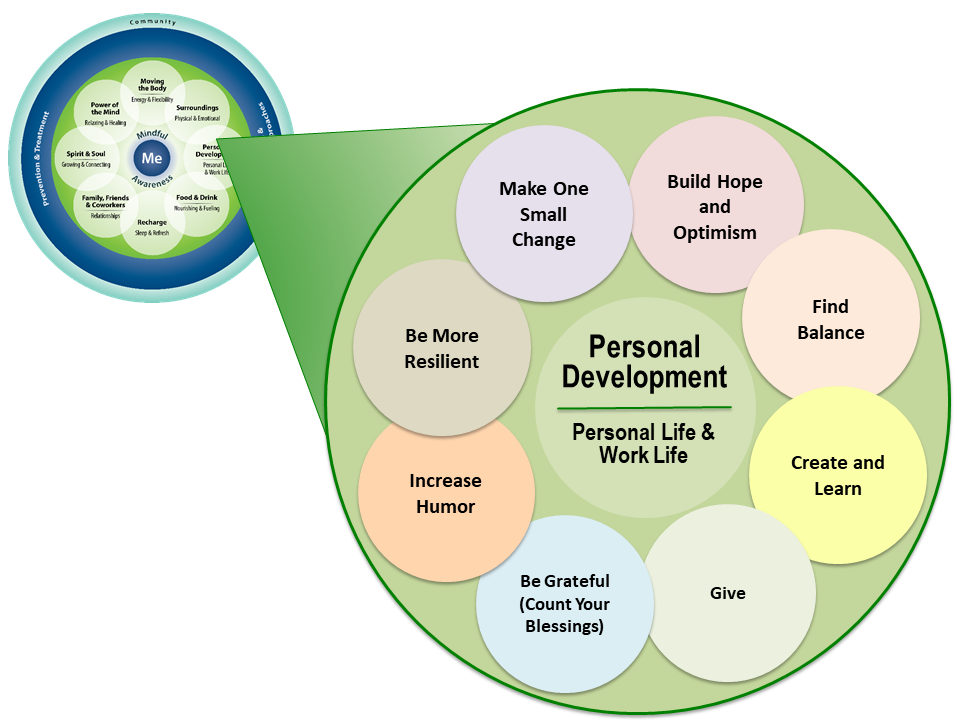

In Fiscal Year 2017, Whole Health skill-building courses were created to help Veterans focus in on specific “subtopics” related to each area of self-care. Figure 1 shows the subtopic circles for Personal Development.

Carl Jung and Abraham Maslow were early contributors to personal development as an aspect of health:

- Carl G. Jung (1875–1961) made contributions to personal development with his concept of individuation.[1] He defined this as the drive of the individual to achieve the wholeness and balance of the Self, which he considered the central process of human development.

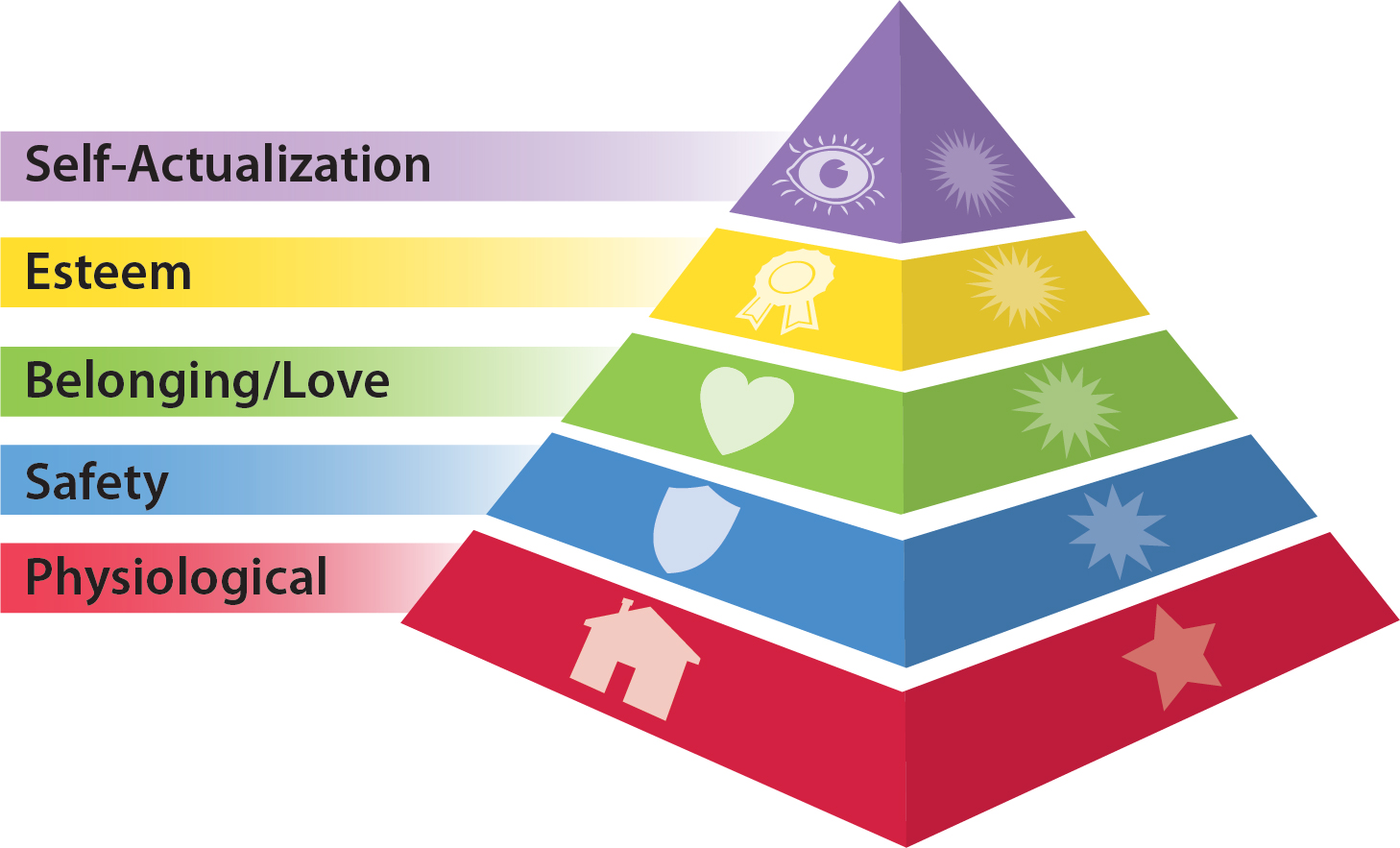

- Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) developed the well-known “hierarchy of needs.” This model suggests that psychological health is based on meeting basic human needs that have different levels of priority (refer to Figure 2).[2] Only when basic needs are met do we have the energy and opportunity to fully engage in higher levels of personal development. Maslow referred to these higher levels as “self-actualization.”[3]

Both Jung and Maslow believed that individuals have a strong need to realize their full potential.

In business or organizational settings today, personal development can be seen as an investment, with the end result being an increase in the economic value of employees. The goal of investing time and money into the personal development of employees might be to increase creativity, innovation, quality and/or productivity.

More recently, the field of positive psychology has emerged with contributions to personal development. Positive psychology has been defined as those, “conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing or optimal functioning of people, groups and institutions.”[4] It is concerned with positive human experiences. These include, but are not limited to

- Gratitude

- Hope and optimism

- Values and meaning

- Forgiveness

- Positive relationships

Research in the area of positive psychology has been steadily building, and it is clear that focusing on positive experiences can be a powerful way to help individuals and groups be successful. [5]

This module will focus on a number of ways to foster personal development. Some of the key research in these areas will be highlighted. In many instances, the content pertains specifically to clinicians, but much of this material is applicable to everyone. For additional information related to “Care for the Caregiver,” refer to the module, “Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care.” The following topics are covered in this overview:

Mindful Awareness Moment

Choosing an Area of Personal Development

Listed above are the 16 areas of personal development discussed in this overview. Take a few moments to choose the one or two that you are most inclined to work on yourself.

- What led you to make your choice(s)?

- How might you focus more on that area? Outline two or three specific actions you can take to make progress in this area.

- In what ways will that area of personal development enhance your overall health?

Quality of Work Life

The Quality of Work Life (QWL) of medical professionals is a subject studied across the globe. Health care environments are known to be demanding, both physically and psychologically.[6]

The nursing profession has been one group of health care professionals whose quality of work life has been examined quite closely. Quality of work life for nursing is associated with:

- Negative patient outcomes[7][8]

- Staffing levels[9][10]

- Staffing mix[11]

- Nurses work schedules (and number of hours nurses worked)[12]

- Overtime[10]

Knox and Irving (1997) in a meta-analysis of QWL among nursing staff found that the following characteristics of the workplace positively impacted QWL[13]:

- Autonomy

- Lower levels of work stress

- Favorable relations with supervisors

- Appropriate job performance feedback, opportunities for advancement, low levels of role conflict

- Fair, equitable pay levels

The Magnet credentialing program for hospitals (American Nurses Credentialing Center) focuses on practice environments of nurses that have an impact on QWL, including leadership, empowerment, professional practice, creation of knowledge, and improvements in quality measures. As of April 15, 2018, there were a total of 475 magnet facilities.[14] Positive outcomes of having such environments include the following:

- For nurses’ QWL: improved working environments, lower burnout rates, higher retention rates, and decreased injuries for nursing staff[15][16]

- For patients: decreased rates of mortality, decubitus ulcer, and falls; improved quality of care

Physician’s poor quality of work life (e.g., excessive workload, loss of autonomy, inefficiency due to excessive administrative burdens, difficulty integrating personal and professional life, etc.) can significantly affect physician “burnout.” Burnout typically comprises feelings of cynicism/depersonalization, loss of enthusiasm for work, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. A large, national, cross-sectional study of physicians found the following[17]:

The prevalence of burnout among U.S. physicians is at an alarming level:

- Physicians in specialties at the front line of care access (emergency medicine, general internal medicine, and family medicine) are at greatest risk.

- Physicians work longer hours and have greater struggles with work-life integration than other U.S. workers.

- After adjusting for hours worked per week, higher levels of education and professional degrees seem to reduce the risk for burnout in fields outside of medicine, whereas a degree in medicine (MD or DO) increases the risk.

Shanafelt and colleagues state that few interventions for physician burnout have been tested, and most have focused on stress management training rather than organization-wide change, such as in the nursing Magnet programs. For example, improving the QWL of residents and fellows through a team-based, incentivized exercise program found that the program increased the QWL scores for participants, compared to nonparticipants.[18] Research on mindful awareness training for clinicians is promising. Krasner et al. demonstrated that an educational program in mindful communication focused on self-awareness improved clinician well-being (burnout and mood).[19] Fortney et al. conducted a pilot study that provided abbreviated, tailored mindful awareness training (18 hours) to 30 primary care clinicians.[20] Data at nine months post-intervention showed statistically significant improved measures of job burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress for these clinicians.

Burnout follows similar patterns for people in other “helping” professions. Teachers, lawyers, mental health professionals, and many other groups demonstrate high rates of burnout. For more information, refer to the Whole Health overview, “Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care.”

Resilience

Building resilience is a fundamental goal of personal development. Resilience, although multifaceted, is commonly defined as involving a positive adaptation to adversity.[21] Resilience includes being able to[22]

- Adapt to changing environments

- Identify opportunities

- Adapt to constraints

- Bounce back from misfortune and challenges

The generation of positive emotions has been associated with resilience.

- Positive emotions broaden our thinking/behavior repertoires, helping us adapt in the face of change or disruption.[23][24]

- Individuals high in resilience do not actually lack negative emotions. Their levels of negative emotions are comparable to those of less-resilient peers. What occurs, however, is that they generate more positive emotions. These researchers conclude that resilience generates positive emotions and positive emotions and resilience build on each other. [22]

Exploring resilience in physicians, Zwack and Schweitzer conducted over 200 semi-structured interviews investigating prototypical processes and key components of resilience-fostering preventive activities.[25] The following themes emerged as being helpful for promoting resilience for physicians (they are relevant for nonphysicians as well):

- Gratification from the doctor-patient relationship, including the following:

- Showing interest in the patient as a person seemed protective in the presence of monotony (Again, this highlights the importance of the personalized and patient-driven approach)

- Feeling that their opinion matters

- Experiencing patient appreciation and gratitude

- Appreciating the medical efficacy of the intervention

- Resilience Practices:

- Engaging in leisure time activity to reduce stress, especially:

- Sports and physical activity

- Cultural activities such as music, literature, art

- Quest for and cultivation of contact with colleagues

- Cultivation of relationships with family and friends. Refer to the “Family, Friends, & Co-Workers” module of the Whole Health website

- Proactive consideration of the limits of one’s skills, handling complications, and addressing treatment errors

- Personal reflection—consciously and regularly taking time to reflect; for approaches to facilitate this, refer to the “Mindful Awareness” overview

- Self-demarcation—physician ability to maintain clearly defined boundaries

- Cultivation of professionalism including continued learning and education

- Self-organization—individual routines and time structures, delegation, and setting priorities all play a role

- Ritualized time out that can occur on a daily, weekly, and/or annual basis

- Spiritual practices—refer to the “Spirit & Soul” module on the Whole Health website

- Other interventions: resilience workshops, cognitive behavioral interventions, small-group problem-solving and sharing,[26] which can be combined with reflection, mentoring, mindful awareness, and relaxation techniques

Happiness

At least since the time of Aristotle, philosophers and religious leaders have asked the question, “How can we become lastingly happier?”[27] The field of positive psychology has researched this topic in the last decade and highlighted a variety of practices to foster the conditions of happiness.

Happiness is an especially important aspect of personal development for health care clinicians to cultivate. When happiness and career satisfaction decline for health professionals, it negatively impacts the work that they do. For example, studies have shown that physicians who report low levels of happiness are more likely to change jobs, have less satisfaction with patient encounters, provide lower-quality patient care, and negatively influence office morale.[28][29][30][31] Happiness can be improved and increased when clinicians shift focus to building skills to manage or limit the workload, improve feelings of work accomplishment, improve career satisfaction and meaning, and manage distress related to patient care.[32]

A widely used theory of happiness includes three distinct aspects[33][34]:

- Positive emotion and pleasure (the pleasant life). This includes positive emotions about the present, past, and future and learning skills to increase the intensity and duration of these emotions.

- Engagement (the engaged life). The focus here is pursuing engagement, involvement, and absorption in work, as well as with intimate relations and leisure. An individual’s highest talents and strengths (“signature strengths”)[35] are identified and used.

- Meaning (the meaningful life). Pursuit of meaning is also central. It involves using signature strengths and talents to belong to and serve something that one believes is bigger than oneself.

Additional happiness research supports the following key findings:

- The most satisfied people are those who orient their pursuit in life toward all three of the above aspects of happiness, with the greatest weight carried by engagement and meaning.[36]

- Happiness is causal and brings more benefits than just “feeling good.” Happy people are found to be healthier, more socially engaged, and more successful. These things all beget even more happiness.[37]

- Seligman tested a signature strengths exercise to increase happiness.[27] After identifying their personal strengths, participants were asked to use them in daily life over a one-week period. They found that this exercise significantly lowered depressive symptoms. Positive effects lasted at least six months.

- Research suggests that there are very concrete benefits to increased happiness. Both prospective and longitudinal studies show that it precedes and predicts positive outcomes such as better life outcomes, financial success, supportive relationships, mental health, effective coping, physical health, and longevity.[22]

- Family support was strongly related to concurrent happiness.[38]

Hope and Optimism

Charles R. Snyder, PhD, a pioneer in hope research, developed the definition of hope used in mental health research. His model of hope has three major components:

- Goals related to a certain situation

- Agency, the belief in one’s personal ability to make things happen to reach the goals

- Pathways, the methods and plans that allow individuals to achieve goals in any situation

Optimism versus hope

Optimism appears to be different from hope, even though the two are related.

- Optimism is more general. It involves the thought/sense that good things will happen in the future.

- Hope, unlike optimism, is more activating in that it helps someone move toward what he or she wants to happen, given that it includes goals, agency, and pathways.

Benefits of hope

In one study, pediatric clinicians with a higher trait of hope were able to enroll more children into a management program for asthma than clinicians with a lower trait of hope.[39] This suggests that the high-hopes clinicians were able to keep moving toward their goal, even though the situation had many obstacles and barriers.

Clinicians themselves appear to benefit from hope. Hope can provide a greater sense that life is meaningful,[40] and it can also be a strong predictor of positive emotions.[41]

Across settings, hope was also related positively to productivity. Lopez found that hope accounted for 14% of productivity in the workplace, which was greater than the influence of intelligence, optimism, or self-efficacy.[42]

Optimism and hope in chronic disease

Reviewers conducted a systematic review on hope and optimism and found that cardiac patients with higher levels of optimism had better outcomes in terms of physical health.[43] Results were not as clear with cancer patients, although it was noted that they suffered fewer negative changes in their condition. More subjective results occurred for the construct of hope although patients with higher levels had more satisfaction and a higher quality of life. Certainly, more research needs to be completed.

Self-Compassion

We can often be so busy taking care of other people that we put our own self-care on the back burner. Without tending to our needs, we can be vulnerable to burnout and become less effective at work and in our personal lives. Authors have suggested that compassion for others is closely linked to self-compassion and ability to engage in self-care.[44][45][46] Thus, developing self-compassion may be pivotal (in health care professionals and others) for avoiding compassion fatigue, and it may enable a clinician to better manage being in close contact with the suffering of others.

Self-compassion involves directing care, kindness, and compassion toward oneself. Neff states that self-compassion involves “being open to and moved by one’s own suffering, experiencing feelings of caring and kindness toward oneself, taking an understanding, non-judgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one’s experience is part of the common human experience.”[47] Self-compassion has three features[48]:

- Self-kindness

When things go wrong, one treats oneself with kindness and care, and less directed criticism and anger. One is reassuring to oneself rather than critical. Self-talk is positive—encouraging and friendly.

- Common humanity

Recognizing one’s experiences, no matter how painful, are part of the common human experience. This reduces isolation and promotes adaptive coping.

- Mindful Awareness

Mindful awareness helps foster a balanced perspective of one’s situation so that one is not carried away with emotion, being mindful of one’s feelings.

Self-compassion is associated with higher levels of positive affect, optimism, and happiness,[49] lower levels of anxiety and depression,[50] and better functioning romantic relationships.[51] Research found self-compassion to be associated with resilience to burnout and happiness and well-being in healthcare professionals.[52] Other research suggests that self-compassion can act as a catalyst for health care professionals to provide compassionate care to others.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59] Research suggests that self-compassionate people react to lab-based stressors in more balanced ways, with lower levels of negative affect and more realistic self-appraisals.[49][60] Self-compassion also predicts greater self-worth stability.[61] A 2014 study by Breines and Chen found that having more compassion toward oneself paradoxically may make people more motivated to improve themselves.[62]

A 2011 meta-analysis found a large effect size when examining the link between self-compassion and depression, anxiety, and stress across 20 studies.[63] Self-compassion has been linked with experiencing better physical health through engagement in health promoting behaviors and lower levels of negative affect.[64][65]

Self-compassion has also been found to be associated with numerous psychological strengths, such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity and exploration, personal initiative, and emotional intelligence.[49][66]

Mindful Awareness Moment

A Brief Self-Compassion Practice

Compassion practices are one of many forms of mindful awareness practice. They are practiced in many spiritual traditions worldwide. These practices usually start with saying a few key phrases about yourself, before you move on to say them for others. These “others” may include a teacher, a loved one, someone you feel neutral about, a challenging person, a group of people, your co-workers, your patients, all of humanity, or even all living things. For now, just start with yourself.

Repeat the following phrases, out loud or to yourself:

- May I be safe and protected.

- May I be balanced and well in body and mind.

- May I be full of loving-kindness.

- May I truly be happy and free.

Repeat them again. Really focus on the meaning of each word.

Repeat them again. This time, focus on the phrase, and try to feel the intention of it. Many people focus on the heart area as they do so.

And repeat a fourth and final time.

How did you feel doing this? How do you feel now relative to before you started? Did you find it hard to say these phrases to yourself? Why or why not?

Forgiveness

Robert Enright, PhD, defined forgiveness as a “freely made choice to give up revenge, resentment, or harsh judgments toward a person who caused a hurt and to strive to respond with generosity, compassion, and kindness toward that person.”[67]

There are a number of common denominators that arise in definitions of forgiveness[68]:

- Not forgiving involves ruminations that may be begrudging, vengeful, hostile, bitter, resentful, angry, fearful of future harm, and depressive.

- Forgiveness is a process rather than an event.

- Forgiveness of strangers or people with whom one does not want nor expect continuing contact is fundamentally different from forgiving a loved one.

- Decisional and emotional forgiveness are different processes:

- Decisional forgiveness involves a decision to control one’s behaviors (e.g., not to engage in activities that increase anger or create contact with the offender). Decisional forgiveness has the “potential” to lead to changes in emotion and eventually behavior.

- Emotional forgiveness is multifaceted and involves changes in cognition, emotion, and motivation, and eventually behavior.

There is a substantial body of research supporting a relationship between hostility and poor health; for example, hostility is linked to heart disease and all-cause, general mortality.[69] Forgiveness, on the other hand, has been associated with many benefits:

- Improved mental health, reduced negative affect or emotions, and increased well-being.[70][71][72][73]

- Decreased stress levels and mental health symptoms.[74]

- Satisfaction with life[73][75]

- Fewer physical ailments, less medication use, reduced fatigue, better sleep quality, and fewer somatic complaints[76]

- Reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and anger[70][73][77]

- Reduced risk of myocardial ischemia and lower total cholesterol to HDL and LDL to HDL ratios among patients with coronary artery disease[78][79] and decreased cardiovascular reactivity[80]

- Self-forgiveness was associated with lower levels of disordered eating behavior.[81]

- Reduction of vulnerability to chronic pain[82][83]

- Decrease in vulnerability to use illicit drugs at post-test and four-month follow-up for substance abusers[84]

Enright and Fitzgibbons outlined four stages of forgiveness.[85]

- Uncovering, this can include processes such as the following:

- Gaining insight into the injustice and subsequent injury and how it has compromised one’s life

- Confronting anger and shame

- Becoming aware of potential emotional exhaustion

- Becoming aware of cognitive preoccupation

- Confronting the possibility that the transgression could lead to permanent change for oneself, including altering the one’s view of the world

- Decision

- Gaining an accurate understanding of what forgiveness is, and making a decision to commit to forgive on the basis of this understanding

- Work

- Gaining a deeper understanding of the offender and beginning to view the offender in a new light (reframing), resulting in positive change in affect about the offender, oneself, and about the relationship

- Deepening

For more information on forgiveness, refer to the Whole Health tool “Forgiveness: The Gift We Give Ourselves.”

Gratitude

Fredrickson states “gratitude and other positive emotions fuel individual growth, development, and resilience.”[86] Gratitude involves noticing and appreciating the positives in life. It is commonly derived from receiving aid from another, an appreciation of abilities, or being in a climate in which one can thrive.

Gratitude is universal and found across all cultures and all people.[88] It is considered a virtue and is different from optimism, hope, and trust. Emmons and McCullough state that the root of the word gratitude is the Latin root Gratia, which means “grace, graciousness, or gratefulness…all derivatives from this Latin root having to do with kindness, generousness, gifts, the beauty of giving and receiving, or getting something for nothing.”[88]

Gratitude practices studied by research are classified into three categories[87]:

- Daily listing of things for which to be grateful

- Grateful contemplation

- Behavioral expressions of gratitude

Empirical research has found that gratitude can improve a person’s sense of personal well-being in two ways[88]:

- As a causal agent of well-being

- Indirectly, as a means of buffering against negative states and emotions; it makes one more resilient to stress

A number of researchers have proposed a theoretical relationship between gratitude and well-being. Experiencing gratitude, thankfulness, and appreciation tends to foster positive feelings, which in turn contribute to one’s overall sense of well-being.[88][89]

Gratitude has been linked to a host of psychological, physical and social benefits:

- Self-reported physical health[90]

- More feelings of happiness, pride, and hope [91]

- A greater sense of social connection among many others and cooperation—feeling less lonely and isolated[92] and helps maintain intimate bonds.[93]

- A reduction in risk for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders[94]

- Improvement in body image[95]

- Spurring acts of kindness, generosity, and cooperation[96][97]

- Resilience in the face of trauma-induced stress, recovering more quickly from illness and enjoying more robust physical health[98]

- Improvement in sleep and energy[99]

A gratitude practice of writing five things one was grateful for once or twice a week was found more beneficial than daily journaling long-term. One study showed that writing once a week for six weeks boosted happiness while writing three times a week did not.[100]

Interestingly, experiencing feelings of gratitude has been found to reduce financial impatience more than feeling “neutral or happy.” Participants in a recent study had to choose between receiving $54 immediately or $80 after waiting for 30 days. Those feeling more grateful showed a willingness to wait for the larger amount, while those feeling neutral and happy showed a stronger preference for immediate payouts.[101]

For more information on gratitude, refer to the “Creating a Gratitude Practice” Whole Health tool.

Random Acts of Kindness

A random act of kindness is defined as something a person does for an unknown other, that he or she hopes will benefit that individual.[102] Examples include paying for the order of the person behind you in the drive through, putting money in a parking meter for someone whose meter has expired, and giving a stranger a flower.

Kind acts have been found to positively correlate with enhanced life satisfaction.[103] Lyubomirsky and colleagues conducted two 6-week-long interventions where participants performed five kind acts in one day every week.[37] Participants experienced an increased sense of happiness, an effect not found in the control group.

Buchanan and Bardi conducted an experiment where participants performed new acts of kindness every day for 10 days and found it increased life satisfaction compared to a control group.[102]

FMRI scans show that even the act of imagining kindness or compassion activities activates the soothing and affiliation parts of the brain’s emotional regulation.[104] Kindness, therefore, can become a self-reinforcing habit requiring less effort over time to engage in and creating new neural connections.[105] Creating and encouraging a culture of kindness in health care can be an effective way to promote resilience and provide a buffer against stress and burn-out.[106]

Mindful Awareness Moment

A Random Act of Kindness

This mindful awareness exercise takes a bit more than a “moment” to complete. Start by taking a moment right now to consider what you could potentially do for another person as a “random act of kindness.” How do you feel as you imagine following through with one of the acts that comes to mind?

Now, sometime in the next 24 hours, perform an act of kindness, and when you have finished, ask yourself the following:

- How did I feel as I did it? (If you did not do it, why was that?) Did I feel nervous? Excited? Sheepish? Happy? Something else?

- Did it feel the way I anticipated it would feel?

Repeat this exercise as often as you would like. You might even try performing a random act of kindness for yourself.

Humor & Laughter

The old man laughed out loud and joyously shook up the details of his anatomy from head to foot and ended by saying that such a laugh was money in a man’s pocket, because it cut down the doctor’s bills like everything.

—Mark Twain, Tom Sawyer

Humor, if utilized in the right way, can help to relieve stress in the workplace and at home. It can even, perhaps, help with pain. Humor is a reactive experience, and most definitions of it draw in elements of unexpectedness, surprise, anticipation, incongruity, or incompatibility.[107] Sense of humor is highly individualized; therefore, gender, age, ethnicity, etc., need to be considered. The study of humor and laughter, and its psychological and physiological effects on the human body, is called gelotology.

There are a number of known benefits of laughter and humor:

- During laughter, various muscle groups are activated for periods of seconds at a time, while the period immediately following a laugh leads to general muscle relaxation that can last up to 45 [108]

- Engaging in intense laughter leads to increased heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen consumption—similar to physiological changes noted in aerobic exercise.[109]

- Research examining how laughter influences stress hormones has shown conflicting results.[110][111] Some studies conclude that laughter decreases stress hormones and may act as a buffer to the effects of stress on the immune system.[112][113][114]

- Researchers found that older patients who completed a Humor Therapy program had significant decreases in pain and perception of loneliness. There were significant increases in happiness and life satisfaction in the experimental group but not for the control group.[115]

- In a systematic review of the literature, these reviews found that humor undoubtedly has a role in palliative care but requires training for its appropriate use.[116]

- Humor may relieve self-reported stress and arousal.[114]

- There is some evidence to suggest that simulated laughter (Laughter Therapy or laughter yoga) has effects on certain aspects of health and well-being though further well-designed research is warranted.[117][118]

- A sense of humor appears to be part of the multifaceted and multicomponent experience of wisdom.[119]

Formed in 1987 by a registered nurse, the Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor (AATH) is a nonprofit, member-driven, international community of humor and laughter professionals and enthusiasts. To learn more refer to the AATH website.

For additional information, refer to “The Healing Benefits of Humor and Laughter” Whole Health tool.

Creativity

Creativity can be defined as the generation of something new, different, novel, or as taking something already known and elaborating on its uses, characteristics, or evolution. It can refer to a process (the “creative process”) or to the product that is generated from the process.

Trunell and colleagues identify four aspects of creativity[120]:

- Supportive environments and intrinsic (inner) motivation enhance creativity.

- Intrinsic motivation is enhanced by the completion of tasks.

- Creativity involves both divergent and convergent thinking.

- Divergent thinking promotes the generation of many new ideas. An example is brainstorming all the possible uses for a paperclip.

- Convergent thinking focuses on finding the solution to a particular problem. For example: What do a horse, plane, and boat have in common? They are all forms of transportation.

- Analogies and metaphors enhance creativity.

Recent research on creativity sheds light on some influences on creativity. Meditation techniques can promote creative thinking. Colzato and colleagues found that certain types of meditation fostered divergent processes of thinking.[121] Practice of a type of meditation called “Open Monitoring,” during which a practitioner is receptive to all thoughts, sensations, experiences, and emotions without singling one out, appeared to generate more new ideas for the intervention group versus controls. A 2010 meta-analysis demonstrated that a lack of control significantly stifles creativity.[122] The same meta-analysis noted that creativity and stress have a complex relationship that cannot be simplified down into exclusively positive and negative impacts.[122]

To increase creativity the following is suggested by creativity research[123][124]:

- Use an idea notebook, voice recorder or even a napkin in a restaurant to capture ideas when they arise.

- Surround yourself with things, events, and people that are interesting or novel to stimulate new thinking.

- Broaden your knowledge base by taking a class or learning something outside your area of expertise. This allows for more diverse knowledge to become available for interconnection during the creative process.

- Seek out challenging tasks that might not even have a solution. This causes old ideas to compete with each other and helps generate new ones.

- If you are trying to solve a problem, sleep on it. One study suggested that sleep may help problem-solving and that solutions may even come in the form of a dream. [125]

In medical school, literary creative writing has been suggested as a means to “promote not only self-expression and self-awareness, but also the ability to observe, listen, and empathize” for the developing physician.[126] This self-awareness, or ability to reflect, is also discussed in the lifelong learning section of this module. For detailed information, refer to “Narrative Medicine” Whole Health tool.

Work-life Balance

Work-life balance is defined by Hill and colleagues as “the degree to which an individual is able to simultaneously balance the temporal, emotional, and behavioral demands of both paid work and family responsibilities.”[127] It has been defined by Streu et al. (2011) “as the perceived sufficiency of time available for work and social life.”[128] It has also been defined more broadly as maintaining an overall sense of harmony in life.[129] Cultivating work-life balance is an iterative process that involves acknowledging, adapting, and adjusting personal priorities and situations in response to a myriad demands. What balance means to an individual will change depending on their personal and career situations and involves constant reassessment and decision-making depending on evolving factors in both work and life.[130]

A joint report from the Center for American Progress and the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law found that 90% of mothers and 95% of fathers report work-family conflict.[131] Failure to achieve balance between work and home life has been associated with reduced job and life satisfaction, impaired mental health, family conflict, and ultimately burnout.[132]

Chittenden and Ritchie identify the following strategies one can follow to enhance work-life balance[133]

Work with time-shifting and mindful awareness

This is the ability to “downshift”, to develop an awareness of the body using mindful awareness or cultivating awareness of thoughts and sensations in the present moment. This practice allows one to feel that time slows down. This reduces stress, increases happiness, and makes a person more efficient.

Set goals

Goals should be guided by personal values. One method involves writing down 10 long-term goals every day for a week. At the end of the week, identify the 10 goals that most consistently appear in the daily lists. Then write down the steps to make each of these 10 major goals possible, breaking them down into yearly, monthly, weekly, and even daily tasks. It can be helpful to also write a personal vision or mission statement to set clear priorities both professionally and personally. An important step is to regularly monitor how these goals are being met. This can lead to clarification about goals (are they unrealistic?), about oneself (what factors could be getting in the way?) and about one’s values (are these goals truly in alignment with my personal values?). Refer online to the “Values” Whole Health tool for more information.

Apply the principals of SMART goals (a few at a time) to focus on how to reach each goal. For more on how to set SMART goals refer to the tool in Chapter 3 of the Passport to Whole Health. SMART stands for:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Action-Oriented

- Realistic

- Timed

Use cognitive reframing and build resilience

Another way to improve work-life balance is to become aware of common cognitive distortions that get in the way at work, home, and in finding the balance between these two. Identifying these negative messages and learning how to counter these distortions with more balanced thoughts is a powerful tool in problem-solving and making positive changes.

Practice self-care

Make time for self-care through exercise, adequate sleep, and healthy eating. Finding ways to nurture oneself emotionally and spiritually and to nurture relationships with spouses/partners, children, friends and family are vital to self-care. Engaging in the larger community, and spending time in self-reflection though regular prayer, meditation, and reflective journaling are also components of self-care

Ask for help

Find ways to protect time for family and self by asking for help with daily-living activities, as well as with emotional and spiritual issues. Seek help from work colleagues or mentors when feeling overwhelmed and at risk for burnout.

Additional information is provided online in the “Work-Life Integration: Tips and Resources” tool.

Lifelong Learning

Anyone who stops learning is old, whether at twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. ― Henry Ford

All the world is my school and all humanity is my teacher. ― George Whitman

With the rapid pace of technology and scientific research, we all stand the risk of becoming obsolete and out-of-date if we do not continue reading and studying during our careers.[134] In lifelong learning, emphasis is placed on the development of learner capacity, autonomy, and capability. The goal is to produce learners who are well-prepared for the complexities of today’s workplace.[135] Distance learning is an example of a type of learning that promotes learner autonomy in the rapidly expanding field of technology.

According to Teunissen and Dornan, lifelong learning means striking the “right balance between confidence and doubt.”[136] This includes a goal for professionals to continue to question their actions and knowledge through self-reflection and self-assessment throughout their careers. Professionalism has its core in a commitment to lifelong reflection, self-assessment, and improved performance through learning.[137]

A meta-analysis that included medical students, residents, and practicing health professionals showed that if an orientation toward lifelong learning was high, it continued to grow, even after the completion of formal education or training.[138] Modern clinical practice fundamentally requires lifelong learning and self-reflection, according to Stephenson and colleagues.[139] A lifelong learner has the following qualities:

- Flexibility to change based on practice demands

- Awareness of the need for lifelong learning

- Encouragement of peer review of their work

- The ability to share good practice and knowledge (e.g., through grand rounds, journal clubs, etc.)

- Keeping a reflective diary and reading relevant journals for ideas for improving practice

- A high level of motivation that allows him or her to be a change agent

- Willingness to be challenging and creative in their practice among others

- Resourcefulness and awareness of available resources to support making improvements

Research shows that education is another powerful determinant of health and well-being. There is an association between adult education and midlife cognitive ability including verbal ability, memory and fluency. [140] There is also a link between educational attainment and leukocyte telomere length (LTL), according to a study in the United States where higher education appeared to have a protective benefit against telomere shortening (a measure of accelerated cellular aging).[141]

Education may also promote problem-solving skills, leading to reduced biological stress response, with favorable consequences for biological aging and well-being.[142][143] Educational differences in mortality have been explained in full by the strong association between education and income.[144] Americans’ education and income levels are highly correlated with each other. There appears to be an inverse relationship between all-cause mortality and years of education.[145] Higher education is one of the most effective ways that parents can raise their family’s income.[146]

Leisure & Hobbies

Life away from work has an impact on how people feel and behave at work.[147] Vacations and periods of rest decrease perceived job stress and burnout[148][149] and increase life satisfaction.[148] However, vacation effects fade quickly, and well-being deteriorates soon after a person returns to work.

Thus, individuals need additional opportunities for recovery and recharging from work in the evening and/or during weekends. Setting aside time for leisure activities is an important strategy for coping with stress and negative life events. Leisure has been defined as unobligated time, away from work, personal maintenance, evaluation, and judgment, during which freely chosen and intrinsically motivated activities, both active and passive, social and solitary, are pursued for enjoyment and relaxation toward achieving a state of mind that supports rejuvenation, and contributes to overall quality of life, health, and well-being.[150]

Recovery attained during leisure time has an effect on the following:

- How individuals experience the subsequent workday[147]

- Overall well-being[147]

- Prevention of burnout[151]

- Inhibiting ongoing deterioration in mood and performance over the long term[152]

Engagement in meaningful life activities produces a sense of satisfaction and a belief that life is being well-lived.[153] It is strongly correlated with happiness, too.[37] Lyubomirsky and colleagues note that putting sustained effort into doing these happiness-enhancing activities, rather than doing them for only a week, is essential to their beneficial effects.[100] Repeated effort at cultivating happiness through meaningful life activities can relieve symptoms in mild to moderately depressed individuals and outpatients with major depressive disorder and other affective disorders.[34][154][155]

Leisure experiences, such as engaging in hobbies, can aid in coping with induced stress in ways that are self-protective, self-restorative, and ultimately personally transformative.

Kleiber and colleagues propose the following mechanisms by which leisure is an effective strategy for coping with the stress created by negative life events”[156]:

- Buffer the impact of negative life events by being distracting

- Decrease the impact of negative life events by generating optimism about the future

- Aid in the reconstruction of a life story that is continuous with the past

- Serve, in the wake of negative life events, as vehicles for personal transformation

Participation in leisure activities is also associated with various components of successful aging, including physical health and well-being.[157] Research by Paggi, Jopp and Hertzog (2016) highlighted the importance of leisure activities for successful aging throughout the adult life span.[158] They encouraged engaging in leisure activities that correspond with the level of physical ability throughout life to maintain and even improve well-being.

The online Whole Health tool “Taking Breaks: When to Start Moving, and When to Stop,” has more information on vacations, leisure time, and work breaks.

Volunteering

In 2015 in the United States, an estimated 62.6 million people, or over 25% of the population, volunteered their time and money to a nonprofit organization, spending around 7.9 billion hours of volunteer time (“Volunteering in 2016”)[159] Research provides strong evidence that volunteering has not only social benefits, but positive health benefits as well. The 2007 report, “The Health Benefits of Volunteering: A Review of Recent Research” described a significant association between volunteering and health.[160] This report indicates that volunteers have:

- Greater longevity

- Better functional ability

- Lower rates of depression in later life

- Less incidence of heart disease

In addition to volunteers having improved physical and mental health, they are found to have greater life satisfaction and quality of life. [161][162]

Research has found that volunteering has a positive effect on other social and psychological factors as well, such as [163][164]:

- Increasing a personal sense of purpose and accomplishment

- Enhancing social networks to reduce stress and risk of disease

Research by Clay found that volunteering serves a variety of functions, including the following[165]:

- Values: The individual volunteers to express or act on important values like humanitarism.

- Understanding: The volunteer is seeking to learn more about the world or to exercise skills that are often unused.

- Enhancement: One can grow and develop psychologically through volunteer activities.

- Career: The volunteer has the goal of gaining career-related experience through volunteering.

- Social: Volunteering allows an individual to strengthen his/her social relationships.

- Protective: The individual uses volunteering to reduce negative feelings, such as guilt, or to address personal problems.

Other studies have found that when individuals with chronic or serious illnesses volunteer, they receive benefits beyond what can be achieved through medical care alone. However, a “volunteering threshold” was found; after this threshold was reached (i.e., volunteering in two or more organizations or volunteering more than 100 hours/year), no additional health benefits occur. [166][167]

The Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2012 surveyed thousands of physicians and found that physicians volunteer in the following ways: pro bono local clinical work, work associated with religious organizations, tutoring and/or counseling, local nonreligious volunteer work, international mission/work (e.g., Doctors Without Borders), medical volunteering for natural/man-made disasters, and working with homeless people.

A 2011 review of studies conducted by von Bonsdorff and colleagues highlighted several benefits of volunteering.[168] Outcomes were collapsed into three areas of personal well-being: physical health, mental health, and psychosocial resources. All included studies came from the United States, and all found that volunteering in old age predicted better self-rated health, functioning, physical activity, and life satisfaction; depression and mortality were decreased.

An analysis of the experience of more than 1,700 women who were involved regularly in helping others had these effects[169]:

- 50% of helpers reported a “high”

- 43% felt stronger

- 22% felt calmer and less depressed

- 13% had fewer aches and pains

- 21% had a greater feeling of self-worth

Of the participants, 72%-80% stated that these benefits, such as their helper’s high, would reoccur, though with less intensity, when they remembered helping. The authors stated that the pleasure one receives from being altruistic and volunteering does not seem to arise from donating money, no matter how important the cause, nor from volunteering that occurs without close personal contact.

Financial Health

Financial health often refers to the state of a person’s financial life or financial situation. It is a general term that could include a variety of topics, such as the amount of savings someone has (e.g., retirement, savings account funds, or college savings), how much income is spent on fixed or nondiscretionary expenses such as rent or mortgage, ability to pay debts, etc. Another oft used term is “financial literacy,” which is defined as the ability to make informed judgments and manage money effectively.[183]

Does more money make us happy?

Research has suggested that there is a small but positive association between income and happiness. However, this relationship is not linear; the positive associations between money and happiness decreased significantly at higher levels of income.[184][185] Happiness and income appear more highly associated at lower levels of income, with decreasing effect once income exceeds poverty level.

Financial debt and health

Recent data suggests that those with medical or credit card debt may forego prescription medication prescribed by their clinician, even when net household income, net worth, and other characteristics are taken into account.[186] In a survey conducted by the American Psychological Association, nearly 1 in 5 Americans say that they have either considered skipping (9%) or skipped (12%) going to the doctor when they needed health care because of financial concerns. A systematic review and meta-analysis also found association between debt and health, with more severe debt being related to worse health; however causality is hard to establish.[187]

Money and stress

Financial health and literacy can be a source of stress. The American Psychological Association (APA) conducted a survey and found that stress associated with finances and money is widespread.[188] In fact, 72% of Americans report that finances are a significant cause of stress, and this seems especially true for parents and younger adults. The report suggests some tips to manage financial stressors[189]:

- Pause but do not panic. Panic can create high levels of anxiety and lead to bad decision-making. It is important to avoid the tendency to overreact or to become passive. Remain calm and stay focused.

- Identify financial stressors and make a plan. Assess financial health and take note of what creates stress. Then they commit to a specific plan and review it regularly. Facing financial stress can create more anxiety in the short-term, but putting things down on paper and committing to a plan can reduce stress in the long-term.

- Recognize how one deals with stress related to money. Financial stress can cause a person to engage in activities that create more stress, such as smoking, drinking, gambling, emotional eating, etc. These negative coping techniques can add to stress in family and partner relationships.

- Turn challenging times into opportunities for real growth and change. Economic challenges can motivate one to find healthier ways to deal with stress. Use financially challenging times to think outside the box and try new ways of managing one’s life.

- Ask for professional support. Credit counseling services and financial planners are available to help gain control over one’s money situation.

The American Institute for Research (AIR) conducted a review of the literature and found that financial education and counseling are closely connected to financial health in many ways.[183] Better long-term financial outcomes are associated with highly targeted and proactive counseling. Education assists in managing present difficulties and in preventing future problems. Ongoing peer mentoring, interactive assistance, counseling, and coaching can be crucial in helping consumers attain long-term goals such as financial stability.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, through its 2009 Healthy Relationships and Financial Stability project, developed the following 10 suggestions for healthy family finances[190]:

- Set common financial goals and formulate steps toward that goal.

- Regularly discuss financial and other goals at home.

- Involve the children in the plan.

- Avoid schemes with high hidden fees, like check cashing stores (use banks), rent-to-own (wait and buy), credit cards.

- Pay yourself first. Put something in your account for your future as you pay others for their services.

- Communicate when there is conflict with a partner, child, or company.

- Check credit reports regularly including that of a spouse or partner. Free copies can be ordered annually.

- Make sure the family receives Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and any other government benefits.

- Know when to seek assistance. Key times might be when getting married, getting divorced, having a baby, or adopting a child.

- Know that there are resources available to help, regardless of one’s current financial and family situation.

Resources

Financial Education and Literacy

- Money Smart

- Financial education program created and run by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Money Smart materials are free and can be ordered on the FDIC’s website.

- Financial Knowledge Institute

- Nonprofit educational organization that specializes in onsite workshops on personal financial topics. The speakers are community members who donate their time to share their passion of creating financial literacy.

- Institute for Financial Literacy

- Nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote effective financial education and counseling.

- Money Management International

- S. network of nonprofit agency that provides free professional credit counseling, debt management programs, and consumer education.

- National Endowment for Financial Education

- Information on ways to save money, tips on how to become a savvy saver, a savings quiz, and financial calculators to help figure out how long it would take to save money or pay off a loan.

- Take Charge America

- Nonprofit organization that provides education, counseling, and debt management.

- My Money

- Information from the U.S. Government to help improve the financial literacy and education of persons in the United States.

- Women’s Institute for Financial Education

- WIFE is a nonprofit organization which provides financial education and networking opportunities to women of all ages.

- The American Financial Services Association Education Foundation (AFSAEF)

- An affiliate of the American Financial Services Association (AFSA) is a nonprofit organization to heighten consumers’ awareness of personal financial responsibility. AFSAEF’s mission is to help consumers realize the benefits of responsible money management, understand the credit process, and seek help if credit problems occur.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

- Provides consumers answers to questions about financial products and services, including credit cards, mortgages, student loans, bank accounts, credit reports, payday loans, and debt collection.

Back to Sarah

During her Whole Health visit, Sarah spoke at length with her primary care clinician about Personal Development, which emerged as a priority among the various components of proactive self-care (the green part of the Circle of Health). Her PHI made it clear that she has a lot of good ideas. When creating her Personal Health Plan (PHP) the following was noted:

- Quality of work life

- Sarah is doing well with this. She has great relationships with her colleagues and enjoys what she is doing. She will do more reading about burnout, as she knows she is at risk of this given that she takes care of a number of seriously ill people as a certified nursing assistant.

- Resilience

- She will review information on enhancing resilience and will focus on bringing a greater sense of meaning into her life.

- Happiness

- She recognizes that happiness matters a lot to her, but she has not been a particularly happy person since her divorce. She intends to work on that, mainly through reconnecting with her old church congregation and spending at least one night a week having family game night with her kids and their friends.

- Hope and optimism

- She feels optimistic overall and will continue to model that for her children.

- Self-compassion

- She will practice a Mindful Compassion exercise regularly to cultivate this, as she finds it to be challenging to feel good about herself. (Refer to the “Family, Friends, & Co-Workers” overview for more information.)

- Forgiveness

- She will review the “Forgiveness: The Gift We Give Ourselves” tool and start working on this in terms of how she feels about her ex-husband. She was relieved to learn forgiveness was in no way about condoning any of his past behaviors.

- Gratitude

- Sarah will identify three things she is grateful for every day as she drives home from work.

- Random acts of kindness

- Sarah does these frequently in her healthcare work.

- Humor and laughter

- Sometime down the road, perhaps in a month or two, she hopes to do a laughter yoga session with her care team at the hospital.

- Creativity

- She will begin scrapbooking again.

- Work-life balance

- While this is challenging for her, given all her obligations, she intends to take 20 minutes a day just for herself. She will check in with her clinical team about how that is going after two weeks.

- Lifelong learning

- Sarah is already planning to attend nursing school.

- Leisure time and hobbies

- She will start scrapbooking and having family game night, as noted above.

- Volunteering

- Sarah does not have a lot of time for this right now, but she understands it can have health benefits and will have her kids volunteer with her at an upcoming church activity.

- Social capital

- She will host dinner at her house for her family and friends at least three times a year. After exploring her values, Sarah established a family tradition to take a walk together after Sunday dinner.

- Financial health

- She hopes to find an affordable financial advisor and has the resources listed at the end of the Financial Health section of this module. She spent an afternoon a few weeks ago on a free financial website to create a family budget. Although it is not working perfectly, she worries less because she has come up with a plan.

During Sarah’s visit with her clinician, one of their main tasks was decide on priorities, so that she would not be overwhelmed by the list of possible actions she could take. Ultimately, she decided to start with more time with her kids (scrapbooking, nature time together, and other family time) and spending more time at church to build friendships and incorporate some volunteer opportunities. She will follow up with a member of her care team in one month to explore other options.

Whole Health Tools

Author(s)

This overview was written by Shilagh A. Mirgain, PhD, and Janice Singles, PsyD (2014, updated 2018).

Social Capital

The term “social capital” was first introduced at length by Robert Putnam in his national bestseller, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.[170] The act of bowling alone was used as a reference to the disintegration of U.S. after-work bowling leagues as a metaphor to illustrate the decline of social, political, civic, religious, and workplace connections in the United States.

Social capital refers to various levels of social relationships formed through social networks. It is a complex phenomenon that is the result of social relationships based on reciprocal exchanges between family and friend networks; co-workers; members of social, religious, or political organizations; and residents in the same neighborhood. It can improve the efficacy of a society by facilitating coordinated actions.[171] The core idea is that social networks have value. Similar to physical and human capital, social contacts can increase the productivity of individuals and groups.

People create connections with each other, and these connections are important in a variety of ways. In a classic example of social capital, people who attend the same university usually feel connected with each other, both because they may have formed a friendship attending school together and/or because they share an institution in common. Two graduates of the same university are more likely to connect with each other and provide information or resources because they share social capital.

Other examples of settings where social capital arises include a community garden, a neighborhood running a neighborhood watch program, a church congregation, or people who work out at the same local gym.

A 2014 meta-analysis by Gilbert and colleagues focused on social capital research and found a strong positive relationship between social capital and health as measured by self-reported health and mortality.[172] Kawachi and Berkman conjectured that social capital provides opportunities for psychosocial support which, if accessed, will tend to reduce stress and improve health.[173] Berkman and colleagues suggest that social capital influences health through different pathways.[174] First, social support allows a person to feel cared for and that they belong to a network. Second, there is influence through shared norms. Third, there is social engagement and participation, and lastly there are person-to-person contacts, which are especially pertinent in certain behaviors, such as secondhand cigarette smoking or shared food and beverages.

One study found that social capital at work, having strong social ties with co-workers and a work environment that values and fosters social connections, reduced risks of burnout.[175] Research suggests that low levels of social capital may also negatively impact the quality of care provided for patients, whereas high levels of social capital contribute to increased employee satisfaction and engagement and positive work environment.[176][177][178][179][180][181] Additionally, a study conducted in 15 healthcare settings explored the mediating role of social capital between job performance and employee engagement and recommended facilitating social capital to increase employee performance.[182]

Hofmeyer and Marck (2008) recommend fostering social capital in modern healthcare systems in five dimensions:

Refer online to the “Family, Friends, & Co-Workers” Whole Health overview for more information on how to increase social capital.