Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 2

Chapter 2. Whole Health Clinical Care, Part I: Empowerment, Fundamentals, and Map to the MAP

Chapter 2. Whole Health Clinical Care, Part I: Empowerment, Fundamentals, and Map to the MAP

It is much more important to know what sort of patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.

―William Osler

Most people resonate with the underlying philosophy and principles that define Whole Health. Of course, then they want to know how to move from knowledge to practice. Important questions arise:

- This all sounds great in theory, but how do I make this real?

- What does this look like in my specific practice, or for my specific VA role?

- How does this fit in with what I/we are already doing?

- I have a lot of commitments and responsibilities, and access is a high priority at my site. Is it realistic to think I can do Whole Health as well?

- How do I apply this to my own self-care?

The Whole Health Clinical Care Journey

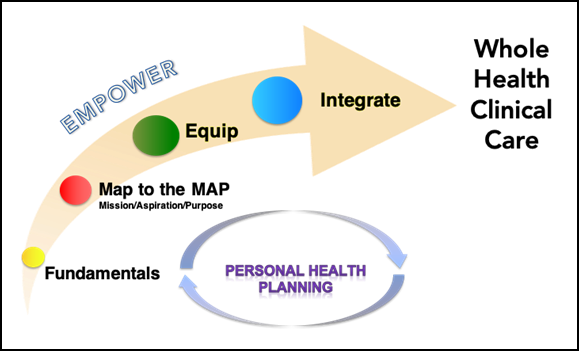

Figure 2-1. The Whole Health Clinical Care Journey

Figure 2-1 illustrates the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey. It captures the various elements that allow people to apply and implement Whole Health. The Journey to Whole Health Clinical Care is cyclical; different elements will come into play at different times as a Veteran moves through the Whole Health System. Moving from left to right on the graphic (but noting they can occur in any order) the journey includes several important elements:

- Empower. As noted in Chapter 1, Whole Health is patient driven. Empowered patients take the initiative with their care, are captains of their care teams, and perpetuate healthy routines in their daily lives. Empowered clinicians and teams have the capacity and support needed to care for patients in whichever meaningful, connected ways patients would like. Whole Health requires an active approach to care; support from professionals is important and maintaining healthy patterns and a steady move toward one’s goals is ultimately up to each individual.

- Fundamentals. It is vital for you to be able to define Whole Health so you can describe it to Veterans and colleagues (Chapter 1 covers this in detail.). Practicing Whole Health is made possible through effective communication, strong therapeutic relationships, and a commitment to care of the whole person—physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and social. Experiences with other programs and resources relevant to Whole Health—e.g., MOVE! Weight Management Program Home, Healthy Living Messages – National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, , Goals of Care Conversation Training, VA Voices, and RELATIONS® for Healthcare Transformation are of great value.

- Map to the MAP. “MAP” stands for “Mission, Aspiration, Purpose.” An essential piece of Whole Health is to build care on a person’s deepest values. Asking why someone wants his or her health in the first place clarifies goals of care, and it leads to a higher level of engagement and follow through. This is the game changer. Here, individuals and teams discover what matters most to the people in their care (their MAP). They connect their work to the MAP by establishing shared goals in partnership with each Veteran, and they document how the Personal Health Plan (PHP) supports the Veteran’s MAP. Clinical team members are empowered to connect to their own MAP and experience Whole Health for themselves.

- Equip. As Veterans pursue shared goals, they need education, resources, skill-building, and support. Clinicians and teams also must be equipped appropriately to provide excellent Whole Health care. As people who will be assisting others, they need to know both what resources and personnel are available to support Whole Health, and also how Veterans can access them. They also need to have resources available to them for their own self-care.

- Integrate. Effective Whole Health care requires seamlessly integrating all these different elements. How can we optimize each Veteran’s experience as he/she seeks Whole Health care? The ultimate goal is to offer cutting-edge care that empowers and equips Veterans to live their lives to the fullest, in support of their MAP, on an ongoing basis. Measurement strategies are put into place to assess impact of all of these elements, and the logistics of the system (e.g., documentation, billing, coding, resource allocation, etc.) support this too.

These elements are also summarized in Figure 2-2. The Whole Health Clinical Care Journey reflects the process of personal health planning; it supports Veterans as they develop their PHPs. The PHP is the documented compilation of the above information, and it is Veteran owned. The PHP may be brief, or expanded, depending on Veterans’ preferences and the degree to which they are involved in the Whole Health System. This is a dynamic document which is now available as a national template titled CPRS Personal Health Plan Template Educational Overview. It can be filled out by multiple care team members over time.

Key Characteristics of Practicing Whole Health Clinical Care

- Considering and caring for the Whole Person

- Practice across teams and over time

- Actively use foundational skills (communication, therapeutic presence, relationship building, and Motivational Interviewing.

- Equip using a broad range of resources and support

- Empower through connecting to Mission/Aspiration/Purpose

- Continue to provide excellent clinical care

- Map to MAP by setting shared goals that link to Mission/Aspiration/Purpose.

PHPs are individualized plans that are built around MAP and focus on meaningful and attainable goals. PHPs include MAP, self-care goals and activities, clinical and complementary care goals, and evolve over time. In the Whole Health Systems model (Figure 1-4), the personal health planning process is central to providing Whole Health care and is a team-based process.

No matter what kind of work you do with Veterans, these aspects of Whole Health care will have some relevance to your work. You may work with all of the different elements of the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey, or you may use just a few. Individuals and teams may be at different places along this journey and evolve over time to deliver more integrated Whole Health care. Remember, you don’t have to draw in all of them at once. Even asking a Veteran or colleague how it is going as they work toward a Whole Health goal is offering Whole Health care at a fundamental level.

One care team member can do a great deal to advance Whole Health, and ideally, their impact can be magnified through the combined efforts of an effective, transdisciplinary team. Whole Health care is not about just one clinician or staff member taking on all the work. It is not the responsibility of any one department either; primary care is essential to moving Whole Health forward, and so is specialty care. Outpatient care and inpatient care work in synergy; there are no siloes. The PHP travels with each Veteran; everyone who takes care of a given Veteran will ideally supporting them around their MAP in some way, even if by simply asking them how they are doing working toward their goals. Busy clinicians find it much easier to imagine working with the Whole Health approach when it is built upon team-based efforts. Continually ask yourself how you can best support Whole Health in your specific role. Honor scope of practice and think outside the box too. Ask for support. Remember (as discussed in Chapter 1) the potential of Whole Health Coaching and Whole Health Partners when it comes to optimizing care and dividing roles among different team members.

Sometimes, people ask which Veterans are best suited to receive Whole Health care. The answer? All of them, if they are willing. Of course, there are various factors you must take into consideration. If someone has an urgent or emergent problem, addressing that must take precedence, of course, but that can nevertheless be done within a Whole Health framework. Some of the most motivated and effective Whole Health clinical champions are Emergency Department personnel. Specific circumstances—such as if a Veteran is living with serious mental illness, homelessness, and/or palliative care needs—all shape how care will look, but they need not stop team members from using the Whole Health approach, as appropriate. Everyone can potentially benefit from mapping to the MAP and other aspects of Whole Health care. You may not ask about MAP at every visit, but you still may connect with it indirectly. Your therapeutic presence, including how you communicate and relate with each Veteran, supports their Whole Health experience. Trust your instincts about when and how to introduce the Whole Health approach to someone.

The rest of this chapter focuses on the first three of the elements of the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey: Empower, Fundamentals, and Mapping to the MAP. The concept of Shared Goals is also introduced. Chapter 3 goes into more detail about Equipping, Personal Health Planning, and Integration.

Empower

Empowering Veterans is central to Whole Health care. When patients are empowered, they are more satisfied with their care, more adherent to the care plan, and have better overall outcomes.[33] What exactly is empowerment? Empowerment has been defined in a number of ways, all of which tie in well with various aspects of the Whole Health approach:

- Being ill, and particularly having one or more chronic disease, can potentially make people feel powerless in every aspect of their lives.[34] Empowerment is about regaining some control. Choosing one’s goals and being able to decide on how they want to reach them can bring a sense of greater power over one’s health.

- Along similar lines, empowerment is also about self-determination.[35] How can people take the initiative to advance their health, despite the challenges they face? Self-determination may involve having choice and influence over which treatments or testing one receives,1 and it may involve exercising one’s choices in other ways, such as deciding to work on a specific aspect of self-care or choosing to try a particular complementary approach.

- Acquiring knowledge, or mastery, related to one’s health brings power as well.[36]

- Empowerment can also come through having support from care professionals (e.g., with shared decision-making, featured in Figure 2-3) and peers.4 Some researchers note that empowerment is closely linked to patient centered care, noting that patients can empower themselves without additional help,[37] though support from others may improve the likelihood of their feeling more empowered.

- Empowerment also involves finding meaning in one’s health challenges. Religion and spirituality can play an important part in this.4 In this regard, empowerment can be closely linked to Mapping to the Map.

- Empowering someone is, in and of itself, a way to enhance health.[38] That is, being empowered increases your chances of being healthy.

Empowerment occurs across the Whole Health System. For example, from the moment they enter VA, or when those who are already enrolled to receive VA care first hear about Whole Health, Veterans are supported by Whole Health Partners. (This is part of the Whole Health Pathway, which is a key part of the Whole Health System, as shown in Figure 1-4). These Veterans, who are employed by the VA, are trained to do the following:

- Recruit Veterans to Whole Health

- Familiarize them with resources

- Introduce them to peer groups and other programs

- Work one-on-one regarding personal health planning

- Help them obtain support services

- Provide ongoing support over time

Whole Health Coaches are also trained to empower Veterans. They have additional training with facilitating conversations about MAP and helping Veterans set goals that matter to them. Coaches help Veterans notice and overcome barriers to achieving those goals, and they support them along the way, guiding them to appropriate resources and clinical care team members.

The training requirements and roles of Whole Health Partners, Coaches, and other non-clinical team members is described in Chapter 1 (Table 1-1). Ideally, all three components of the Whole Health System—the Whole Health Pathway, Well-Being Programs, and Clinical Care—work seamlessly together in ways that optimize Veterans’ ability (to draw on the title of one of the Whole Health courses) to “take charge of my life and health.”

Fundamentals

Since its inception in 2011, Whole Health has been built around grassroots efforts, informed by nationally supported educational programing. Different individuals, teams, and facilities have been encouraged to experiment with how Whole Health can best suit their specific needs. While innovation and creativity at the national, VISN, and local levels are strongly encouraged, individual efforts are the key to program success.

Some important examples of Whole Health fundamentals include the following:

- Whole-Person Care. The Whole Health approach recognizes that all aspects of a person’s life should be taken into consideration, including from what is going on at a molecular level (nutrition, medications), to how they are doing mentally/emotionally, to behaviors (physical activity, preventive care), to the bigger picture (surroundings, connections, spirituality, and relationships). Physical health is absolutely important, and it is only one aspect of health. The different aspects of our health are interconnected, so favorably influencing one may have a ripple effect, benefitting other aspects too. Adopting a Whole Health approach requires that you become comfortable with changing (expanding) the conversation to include a wider array of topics.

- The Circle of Health. The Circle of Health, described in Chapter 1, captures what Whole Health encompasses in the form of a graphic. An entire Whole Health encounter can be built around simply showing someone the circle and asking what areas they want to work on. The Whole Health Library website features Overviews and tools related to each of area of the Circle, and multiple Veterans Whole Health Education Handouts are also organized around the Circle’s various components.

- Clinician Self-Care. The importance of care of the caregiver in Whole Health cannot be overemphasized. It is as important for you to apply the Whole Health approach to your own life as it is for use it with Veterans whom you serve. You get to be the “Me” at the center of the Circle of Health, too! What is your MAP? How do you support it through your self-care? Check out “Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care” to explore this important topic in more detail.

- Therapeutic Presence. One of the most powerful aspects of a Whole Health approach goes with you everywhere: your therapeutic presence. Who you are and the example you set can have a powerful influence on the health of those around you. Aspects of therapeutic presence that have good-quality research supporting their patient-care benefits include the following:

- Empathy, kindness, and compassion

- Effective communication; what you learned in Motivational Interviewing, training or taking the RELATIONS® for Healthcare Transformation course fits in beautifully here

- Working with expectations

- Focusing on strengths

- Fostering engagement

- Offering a safe space to explore, honoring differences in perspectives

- Focusing on what really matters (MAP)

- Practicing what you preach; that is, trying the various suggestions yourself that you recommend to others

- For a detailed review (including a detailed bibliography) on the power of therapeutic presence, refer to “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part II: The Power of Your Therapeutic Presence.”

- Honoring What Is Already Done Well. As noted in Chapter 1, many programs in the VA already support or draw in elements from Whole Health. Of course, clinicians are not being asked to stop using their clinical skills. On the contrary, Whole Health is about ways to make them even more successful at using those skills (while building others, as appropriate).

Whole Health Tool: Introducing Whole Health—Your Elevator Speech

Whole Health Tool: Introducing Whole Health—Your Elevator Speech

Imagine you are on an elevator, and some colleagues step in who are unfamiliar with Whole Health. They ask you to tell them about it. Or, imagine you are talking to a Veteran you have not met before—perhaps at the reception or information desk—and you want to give them a brief introduction to Whole Health care. If you have just 30 seconds to share before the elevator ride is over, or before you need to talk to the next patient in line, what would you say?

It helps to think this through in advance, and the following exercise can help. Take a few minutes to consider the following:

- How do you personally define Whole Health?

- How would you describe the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey to someone who has never heard of it before?

You might want to include some of the following snippets in your Whole Health care Elevator Speech. State them in your own words.

Whole Health...

- Is a different way to approach health care

- Is being adopted by many sites throughout the VA

- Aligns with VA strategic plan and the goals of patient centered care

- Is about personalized, proactive, patient-driven care

- Looks at the whole person

- Respects each person’s individual uniqueness

- Encourages people to focus on MAP by asking, “Why do I want my health?,” “What really matters to me?,” “What brings me joy?”

- Incorporates mindful awareness

- Places importance on prevention and the work of the National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- Honors the value of conventional care, especially for acute health concerns

- Places a high priority on self-care and what people can do to take care of themselves

- Is strength-based, acknowledging what people are already doing well

- Brings in complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, as appropriate

- Can involve creating Personal Health Plans (PHPs) for patients

- Is a team-based approach, with the patient being the captain of the team

- Focuses on improving clinician well-being as well

If you would like, jot down a draft of your Elevator Speech in the space below. This can be written in detail, or it may just be a few bullet points to jog your memory. After you practice it a few times, experiment with trying it out with a friend, a colleague, or some of the Veterans with whom you work. Ask for constructive feedback. If you work with a team, encourage everyone on your team to try this exercise. Determine where and when you will share this summary with patients. You may wish to display posters or cards with the Circle of Health on them to facilitate discussion.

The following are two examples of Elevator Speeches. Note what you like and do not like about each, to guide you as you create your own.

Example 1: Whole Health is a model of care that is getting increased attention in the VA. It focuses on you—your values, your goals, and why it is important to you to be healthy. Care is tailored to you as a unique person, it focuses on preventing problems (not just solving them when they come up), and having you be the main person guiding your care, instead of just having everyone tell you what to do. It focuses on self-care, and you can choose to explore different areas around that. It also involves helping you build the team you need to reach your goals, and that team includes not only you and your clinicians, but also might include your loved ones, fellow Veterans who want to help, Whole Health Coaches, or clinicians of complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, like acupuncture or meditation training.

Example 2: Whole Health focuses on what matters to you, instead of what is the matter with you. It is holistic—every aspect of who you are is important. We want you to have the skills, tools, and team you need so that you can achieve your goals and be in your best possible health. This builds on the great care you have already had in the VA up to this point.

In reality, your Elevator Speech will prove to be more of a discussion starter than simply a “speech” per se. The intent is that it will spark an ongoing dialog, to pique other people’s interest in Whole Health.

Mapping to the MAP

Whole Health begins with a focus on the individual. Care is personalized; it is not enough to practice “cookbook” medicine, where the same things are always done for any given health concern. Even if two people have the same diagnoses on their problem lists, they are going to need and respond differently to different therapeutic interventions. Even identical twins will differ in terms of what health problems they have and their explanations for why they have those problems. Perhaps most importantly, any given pair of people will answer differently when asked what they value most and how they want to bring it more fully into their lives.

Mapping to the MAP is about bringing each individual’s values to the forefront of their care and connecting clinical work directly to what matters most to the Veteran. It has been referred to as the “game changer” when it comes to Whole Health care. It honors individual uniqueness and sets the stage for effective personal health planning. It changes the conversations you have with Veterans and leaves room for more creativity and engagement on their part. People appreciate going over these topics, often commenting (pleasantly surprised) that they have never had someone in health care ask them about such things before. Answering MAP-related questions engages people more fully in their care and increases the odds they will set meaningful, achievable goals. Conversely, it can sometimes be difficult for people to identify their MAP. It may be a new concept for many people, and they may benefit from additional opportunities to self-explore or reflect (e.g., Pathway programs). While not common, this process can sometimes also uncover or highlight challenges relating to depression or suicide risk, indicating the need for additional action.

Care focused on a person’s core values deepens therapeutic relationships,[39] increases patient (and clinician) engagement,1 improves outcomes,[40] and is more likely to lead to successful changes in behavior.[41]

We know that meaning and purpose have a significant impact on health too.

- People with a strong sense of purpose live longer.[42] They are more likely to use preventive health care services,[43] but require other health care services significantly less than people with a low sense of purpose in life.[44]

- A review of 63 studies, including over 73,500 people, found that meaning in life was connected with better ratings of numerous different aspects of physical health.[45]

- Purpose in life correlates with lower incidence of sleep disorders,[46] stroke risk,[47] type 2 diabetes,[48] and reduction of risk of myocardial disease.[49]

- Purpose in life is correlated with better scores for memory, executive function, and overall cognition.[50] It is also linked to a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in older people,[51] as well as maintenance of physical function.[52]

- Meaning in life is crucial to coping and psychological well-being.[53]

The following Whole Health tool offers some guidelines for elucidating what matters most to a Veteran, colleague, or loved one.

Whole Health Tool: Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP)

Whole Health Tool: Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP)

One important method for gathering information is to ask questions that go right to the heart of what is most important to the person. These questions delve into the core values that are most likely to motivate someone to follow through with their goals.

![]()

Examples of “The Big Questions:”

- What REALLY matters to you in your life?

- What do you want your health for?

- What is your mission in life?

- What is your calling?

- What goals are most important to you, and how can being in good health help you to achieve them?

- What brings you a sense of joy and happiness?

- What is your vision of your best possible health?

Try these questions out. Start by answering them for yourself. People’s answers often prove to be quite remarkable. The following are the most common ways people will respond.

- They list specific people in their lives or important relationships. Reviews of literature find that relationships, and particularly family relationships, are the most important source of meaning to people from all cultures and age groups.[54]

- They mention a specific experience, be it travel, a hobby, or a daily activity.

- They talk about overall quality of life and health span (how long you live in a healthy state).

- They are hesitant, or they freeze. If this is the case, give them time to consider their answers and check back in with them later. Alternatively, if they are willing, you can have them complete an exercise to identify their values, which might help. Some exercises to explore values are offered in Chapter 7, “Personal Development.”

Some people prefer to use the term “meaning” instead of “mission” as part of MAP. Frame these questions using the wording that is most appropriate for each individual.

Once a person’s MAP has been outlined, the focus becomes setting shared goals that are connected to it.

Conclusion

This chapter introduced the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey and went into more detail about several of the important elements: how to Empower people when it comes to their health care, Whole Health Fundamentals, and Mapping to the MAP. Keep each of these areas in mind as you explore ways to bring Whole Health into your work. The next chapter will focus on the other three elements— Equipping, Personal Health Planning, and Integration.

Resources for the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey

In addition to the resources listed below, a more extensive resource list relevant to the Whole Health Clinical Care Journey is included at the end of Chapter 3.

Websites

VA Whole Health and Related Sites

- Veterans Whole Health Education Handouts. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-handouts/index.asp

- CPRS Personal Health Plan Template Educational Overview. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/:w:/r/sites/VHAOPCC/_layouts/15/Doc.aspx?sourcedoc=%7B187F7E02-62A3-44A4-9D9C-894C706DA474%7D&file=PHP%20template%20educational%20overview_5-7-2019.docx&action=default&mobileredirect=true

- MOVE! Weight Management Program Home. https://www.move.va.gov

- Health Living Messages. VHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. https://www.prevention.va.gov/Healthy_Living/

- Goals of Care Conversation Training. https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/practitioner.asp

- Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery-Mental Health. http://vaww.mentalhealth.va.gov/rc-psy-rehabilitation.asp

- VA Voices. https://news.va.gov/103024/veterans-support-connect/

Whole Health Library Website

- Whole Health Library. https://www.va.gov/wholehealthlibrary/

- Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life: Clinician Self-Care. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/self-care/index.asp

- Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part II: The Power of Your Therapeutic Presence. Overview. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/overviews/part-ii-power-therapeutic-presence.asp

- Brief Personal Health Plan Template. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/docs/Brief-Personal-Health-Plan-Template.pdf

- Long Personal Health Plan Template. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/docs/MyStory-Personal-Health-Inventory.pdf

Other Websites

- RELATIONS® for Healthcare Transformation. The Institute for Healthcare Excellence. https://www.healthcareexcellence.org/relations-for-healthcare-transformation-2/