Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 14

Chapter 14. Introduction to Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches

For many Americans, alternative therapies represent a new discovery, but in truth, many of these traditions are hundreds or thousands of years old and have been used by millions of people worldwide. One must realize that while treatments may look like alternatives to us, they have long been a part of the medical mainstream in their culture of origin.

―C. Everett Koop, former U.S. Surgeon General

Complementary and Integrative Health in the VA

In addition to conventional clinical treatments, self-care strategies, and prevention, Whole Health is inclusive of complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches. CIH approaches are specifically mentioned in the Professional Care circle in the Circle of Health because of their importance in patient centered care. Data from the National Health Interview Survey suggests that 59 million Americans aged over four years had at least one expenditure related to CIH, with out-of-pocket expenditures of $30.2 billion in 2012.[904] A 2017 national convenience sample of 3346 Veterans found that in the past year[905]:

- 52% had used any CIH

- 44% had used massage therapy

- 37% had used chiropractic

- 34% had used mindfulness and 24% had used other types of meditation

- 25% used yoga

The main reasons Veterans used these approaches was for stress reduction/relaxation or pain. 84% said they were interested in trying/learning more about one or more CIH approaches.

Some CIH approaches remain controversial, while others are gaining greater acceptance among hospitals and medical clinics. With new mandates requiring that certain integrative therapies be offered to all Veterans (described below under “List One” and “List Two”), availability of these approaches is increasing.3

Definitions

Originally, providers used the term “Alternative Medicine” and later “Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM)” to describe medical practices that were not considered mainstream. Other terms used over the years have included “Holistic Health” and simply “Complementary Medicine.” The term “Integrative Medicine” came into use in the 1990s as increasing numbers of clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and patients explored the roles that various approaches might play as a part of integrated Personal Health Plans (PHPs) for patients. The idea is that multiple therapeutic approaches may synergize to optimize health. CIH approaches are effective at empowering patients,4 giving them a sense of control over their health,5 and personalizing care.7

According to the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health,

Integrative medicine and health reaffirms the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient, focuses on the whole person, is informed by the evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapeutic and lifestyle approaches, health care professionals, and disciplines to achieve optimal health and healing.vii

In January 2015, the National Institutes of Health changed the name of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). With this title change, the term “complementary and integrative health” became increasingly commonplace. An important example is the use of CIH in section 932 of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), passed by Congress in July 2016. Section 932, entitled “Complementary and Integrative Health,” directed the Department of Veterans Affairs to report on plans for expanding CIH, particularly for substance use disorder and pain management.8 In January of 2020, the ten-member Creating Options for Veterans’ Expedited Recovery (COVER) Commission, in accordance with CARA, released a report to the President with a list of ten recommendations to guarantee Veterans can receive the comprehensive mental health care they need.9 The second recommendation in this report was to “establish an ongoing research program focused on testing and implementation of promising adjunctive CIH modalities associated with positive mental health, functional outcomes, and wellness that support whole health and the VA Health Care Transformation Model.”

There are disagreements about which therapies should or should not be classified as “complementary.”10 For example, in many research studies, chiropractic is considered complementary, but in the VA, it is classified as mainstream and has not always been discussed in surveys related to VA’s CIH offerings. Furthermore, many mind-body approaches are widely used by specialties such as mental health and not considered to be outside the mainstream by these linicians, but they are nevertheless classified as CIH approaches by many researchers.11

What Are These Approaches Used for?

According to the Healthcare Analysis Information Group (HAIG) survey of 2015, which surveyed sites about use of an array of different CIH practices, the five main conditions for which CIH approaches are used in the VA include11:

- Anxiety disorders

- Depression

- PTSD

- Stress management

- Musculoskeletal pain

In short, the conditions for which people most commonly seek CIH approaches are related to pain and mental health. In general clinicians and patients are more likely to seek CIH approaches for conditions that are chronic, complex, and/or not easily treated within the conventional medical model.

The Integrative Health Coordinating Center

Established within the VHA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) in 2014, the VA’s national Integrative Health Coordinating Center (IHCC) focuses its efforts on introducing safe and effective CIH approaches into VA facilities. The IHCC has two major functions:

1. Identify and remove barriers to CIH provision in the VHA System.

2. Serve as a clinical, educational, and research resource for Veterans, clinicians, and VA leadership.

Focus areas of the IHCC include:

- Working with the VA Office of Regulatory and Administrative Affairs to modify the standard medical Benefits Package as appropriate to offer CIH Services. This includes the 2017 directive to advance CIH,7 current work on proposed regulation change, and exemption of co-payment for well-being approaches.

- Tracking field implementation of the CIH Directive. Since 2017, IHCC has been monitoring delivery of CIH approaches on List One in all facilities in an effort to help sites implement care through face-to-face or virtual means. IHCC maintains a utilization report based on Char 4 codes, CPTs and health factors.

- Defining new occupations related to Whole Health and CIH. For instance, VHA has finalized the qualification standards for the occupation of licensed acupuncturist, which is officially a VHA profession. The Massage Therapist Qualification Standard was released in March of 2019.8 Position descriptions have also been created for yoga and tai chi instructors. IHCC continues to work with VHA Human Resources on modernization efforts to streamline positions and hiring practices.

- Outlining business processes. The IHCC has created “clinic stop codes” to track the utilization of CIH approaches. These include codes 159, a CIH Treatment Stop Code, and 139, a Well-Being Stop Code. 139 is non-billable in the primary position. 159 carries a $15 co-pay, but only for category 7-8 Veterans. Both can be in either the primary or secondary position. There are now multiple CHAR 4 codes for an array of CIH approaches. Of note, Whole Health is in price category 4 in the Veterans Equitable Resources Allocation (VERA). Ten days of care will allow a Veteran to qualify for that category, and care can include CIH approaches as well as many other self-management, stress-reduction, educational, rehabilitation, and psychology CPTs. Clarification around what the nature of those visits would need to be is ongoing, in coordination with the Allocation Resource Center (ARC). Refer to the resource list at the end of this chapter for Coding Guidance resources.

- Preparing the current workforce for changes related to CIH provision. IHCC collaborates closely with the developers and faculty for the various Whole Health clinical and non-clinical courses sponsored by OPCC&CT. Online offerings also include various TMS and TRAIN courses that provide continuing education credits, including Introduction to Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches, Clinician Self-Care: You in the Center of the Circle of Health, Eating for Whole Health: Introduction to Functional Nutrition, and Mindful Awareness. Two other one-hour courses were recorded in 2019: Complementary and Integrative Health in Your Practice and Complementary and Integrative Health—A Closer Look at List One Approaches (VA Directive 1137 “List One”). Chapter 3 has more information on these courses, and a current list of available courses can be found on the Whole Health Education home page under Whole Health TMS Modules. In addition, IHCC offers clinical hypnosis training for VHA clinicians and will offer Guided Imagery Foundations and Certification courses.

- Expanding access to CIH services through use of Telehealth modalities (TeleWholeHealth, discussed in Chapter 3), volunteer providers, and virtual courses. With the COVID pandemic, all of the OPCC&CT Whole Health courses were modified to be offered in a virtual format. Additionally, many services such as Tai Chi and Yoga are offered virtually.

- Building a CIH research portfolio, in coordination with VA research partners. Examples of their research findings include the HSR&D evidence maps, many of which are featured or cited in this reference guide. A large initiative including NIH, VA, and DoD is focusing on CIH and pain. Another study focusing on CIH in mental health care is also underway. CIH is an integral part of the Whole Health System of care, and there is now a report by the Center for Evaluating Patient-Centered Care in VA (EPCC-VA) which provides a progress report on outcomes for the Whole Health Systems Pilot at the 18 Flagship Sites.14

- Partnering with groups outside of OPCC&CT, including the DoD, various VA Program offices, and NCCIH.

- Working closely with the Office of Community Care to inform delivery of CIH approaches in the community. As part of MISSION Act, CIH approaches provided through Directive 1137 List One (see below), are a part of the Veterans’ Medical Benefits Package. CIH providers will be a part of the new community care network contract (excluding guided imagery and yoga).

- Partnering with workgroups for the new electronic health record within VHA in order to include necessary elements for scheduling and documenting CIH encounters.

Approval process for additional CIH approaches.

The IHCC serves as the principal advisor to the Under Secretary for Health on CIH-related strategy and operations, to include analysis of any legislation or proposals that would impact or pertain to the delivery of CIH practices within VHA. In 2016, at the direction of the VA Under Secretary for Health, IHCC formed an Advisory Group to plan for the introduction of CIH formally into VHA. The IHCC Advisory Workgroup (IHCCAW) is made up of subject matter experts and leaders from various VA Program Offices.

The role of the IHCCAW is to evaluate and advise on which CIH approaches should be moved forward in VHA and in what timeframe. The IHCCAW serves in part as a national consult service for the field and reviews CIH approach approval requests (from VISN Directors, Facility Directors, or VA practitioners). Based on complete review, the workgroup makes its clinical recommendations to IHCC. IHCC forwards positive recommendations from the IHCCAW to the VHA National Leadership Council’s (NLC) Whole Health Experience Committee (WHEC), and then to the Under Secretary for Health (USH), for final approval.

VHA Directive 1137—Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH) was approved by the Acting Under Secretary for Health on May 19, 2017. The CIH Directive establishes internal policy regarding the provision of CIH approaches in VHA and features two lists of CIH approaches.

LIST ONE currently includes:

- Acupuncture

- Biofeedback

- Clinical Hypnosis

- Guided Imagery

- Massage Therapy (for pain)

- Meditation

- Tai Chi/Qi Gong

- Yoga

The eight complementary approaches featured on List One are subject to the clinical caveats 1 and 2 below. Given the level of evidence supporting their use, they must be made available to Veterans across the system, either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Note: chiropractic care is not included in this list as it is covered under earlier policy.

Clinical Caveat 1: Adequate evidence exists to support the use of the above-subject practices together with conventional care, reflecting current opinion and practice in the medical community. This listing serves, however, as only guidance. Whether any of these CIH approaches is in fact appropriate for a particular Veteran (or other person) must still be determined by the practitioner (together with the responsible treating provider if the practitioner is not also that) in the exercise of their joint clinical judgment and accounting for the patient’s individual clinical factors. In instances when there is no consensus, practitioners will defer to the responsible treating provider. Care will account for the Veteran’s preference, if known, as well as any contraindications to treatment.

Clinical Caveat 2: Some CIH approaches evolve into conventional care modalities over time, and some may end up being pulled from practice. Identifying CIH approaches for use in Veterans’ personalized health plans is a fluid and dynamic process. VHA practitioners need to verify on the VHA’s Intranet SharePoint site that a CIH approach they wish to practice is still on either List One or List Two. These listings will be up-to-date and should be given priority over the listings below, which must await formal policy revisions to be updated

To learn more about the List One CIH approaches, go to the following chapters of this reference guide:

- Chapter 5: Tai Chi/Qi Gong and Yoga

- Chapter 12: Biofeedback, Clinical Hypnosis, Guided Imagery, and Meditation

- Chapter 16: Massage Therapy

- Chapter 18: Acupuncture

Use of the List One approaches is now tracked, and overall, it has been increasing (Table 14-1). All sites are providing CIH; different sites are at different phases of implementation.

Table 14-1. Percentage of VA Sites Using List One Approaches in FY20*

Approach

Percentage of 141 Sites Offering

Acupuncture/Battlefield Acupuncture

91%

Biofeedback

69%

Clinical Hypnosis

33%

Guided Imagery**

57%

Massage Therapy

79% (includes manual therapies done by non-massage therapists as well)

Meditation/MBSR*

83%

Tai Chi / Qi Gong

82%

Yoga

84%

*From directive data.

LIST TWO includes optional CIH approaches. Subject to caveats 1 and 2 (outlined above), the Under Secretary for Health, acting through the IHCC under OPCC&CT, sanctions the optional use of the CIH approaches on this list. CIH approaches are included because they are generally considered by those in the medical community to be safe when delivered as intended, by an appropriate VHA practitioner or instructor. They may be made available to enrolled Veterans, within the limits of VA medical facilities. It is important to note these approaches must still only be offered by practitioners who have proper scope of practice and appropriate training.

List Two includes the following:

- Acupressure

- Alexander Technique

- Animal-Assisted Therapy

- Aromatherapy

- Biofield Therapies

- Emotional Freedom Technique

- Healing Touch

- Reflexology

- Reiki

- Rolfing

- Somatic Experiencing

- Therapeutic Touch

- Zero Balancing

Note that some modalities classified as CIH approaches in past VA site surveys, such as the HAIG report,11 are already integrated into VA services and are not on either list. These include chiropractic as well as art and music therapy (which are classified under recreation therapy).

If you are providing an approach that is not on List One or Two and would like the IHCCAW to review, please send your request to integratedhealthservices@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com. Resources for additional information on the work of the IHCC and regulatory efforts surrounding CIH are provided at the end of this chapter.

Perspectives on Complementary and Integrative Health

Everyone who works with Veterans can benefit from taking a moment to consider the following questions:

- How often do patients, colleagues, or family members bring up the topic of CIH approaches with you?

- Do you ever find that patients do not disclose their use of CIH to you as a member of their care team?

- How do you feel when they do share their interest in CIH? Angry? Uncertain? Frustrated? Enthused? Interested? Does this vary depending on which therapy is being discussed? Which CIH approaches are you comfortable with, and which ones elicit concern?

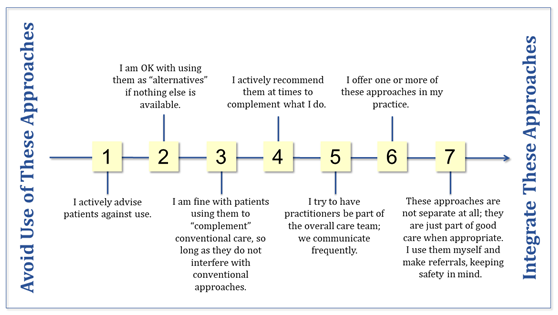

- Pick a CIH approach you have recently discussed with someone. Where would you place yourself on the “Spectrum of Complementary and Integrative Health” (Figure 14-1), and why? It might be instructive to compare your responses with those of your colleagues. Do you feel differently depending on which approaches are being discussed?

Figure 14-1. The Spectrum of Complementary and Integrative Health

Diagram showing the Approaches to CIH that should be avoided/integrated, indicating the following: Graphic consists of a horizontal spectrum ranging from one to seven, with the higher numbers indicating approaches that should be integrated/are more desirable. Under 1, it reads I actively advise patients against use (of CIH). Number 2 reads I am OK with using them as "alternatives" if nothing else is available. Number 3 reads I am fine with patients using them to "complement" conventional care, so long as they do not interfere with conventional approaches. number 4 reads I actively recommend them at times to complement what I do. Number 5 reads i try to have practitioners be part of the overall care team: we communicate frequently. Number 6 reads I offer one or more of these approaches in my practice. Number 7 reads these approaches are not separate at all: they are just part of good care when appropriate. I use them myself and make referrals, keeping safety in mind.

![]() Whole Health Tool: The ECHO Mnemonic

Whole Health Tool: The ECHO Mnemonic

How do you decide if a complementary and integrative health (CIH) approach would be worth recommending or using in your practice? One simple tool you might use is the ECHO mnemonic. The four letters in the word ECHO stand for Efficacy, Cost, Harms, and Opinions. All four components of ECHO are equally important.

Efficacy

What does the research tell us about how well something works? Where are there gaps in the research? What do we (and our patients) know about efficacy from our past experiences with using these approaches?

It is always worthwhile to know the state of the research on a given therapy, be it CIH or otherwise, recognizing that there is not the same financial impetus to study various CIH approaches as there is to study pharmaceuticals or devices used in medical procedures. Fortunately, the NCCIH has done much to advance CIH research.

Research in CIH modalities may be difficult because the mechanism of action may not correlate with current scientific principles, or because aspects of a treatment or desired outcome are difficult to measure, define, or manipulate. Some therapies are highly individualized, and skills may vary greatly from one practitioner to the next. Blinding and placebo control can be a challenge for some therapies, and when an entire medical system, like Ayurveda or naturopathy is being used, multiple therapeutic approaches might be used simultaneously.10

It can be helpful to review the evidence maps, created by VA’s Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D). These are featured in the Resources section at the end of this chapter and are highlighted throughout this reference manual.

Costs

Is the therapy cost-effective? How much would a patient have to pay out-of-pocket for this therapy? Would services be covered at all by insurance or other social programs? How challenging is it for a person to access this therapy, in terms of wait times or transportation? It’s worth nothing that some people will pay thousands of dollars out-of-pocket for CIH approaches.

Harms

What does the research tell us about the potential for harm? How well can a given therapy mesh with other therapies a patient is currently receiving? Are there any possible interactions between different therapies, such as between medications and dietary supplements?

In 2000, a group of female researchers posed as being eight weeks pregnant with nausea. They asked health food store clerks for advice and found that 89% of the time, clerks were willing to offer advice, but 15% of the time, products suggested were contraindicated in pregnancy. When ginger was recommended as an antiemetic, the suggested dosing was not what was supported by the latest research. Thus, the more you can help people make informed decisions, and the more you are aware of potential risks of CIH therapies, the better.

The List One therapies tend to be quite safe overall, but it is still important to be able to know when they are indicated. It helps to know which providers in your community are the most skilled with different approaches. If something is relatively safe, it is easier to feel justified in trying it, even if there is limited information available about efficacy. Additionally, make certain that taking time to try a given CIH approach will not inappropriately delay the use of a proven conventional treatment.

Opinions

Does the therapy match the personal opinions, beliefs, and culture considerations of the person who will be using it? Where are they getting the information that is informing their opinions?

People have strong beliefs about the CIH approaches they have chosen, often based on positive personal experiences. We know that a therapy’s success is linked to how strongly a patient believes in it.16 Matching treatments to people’s belief systems increases their likelihood of being engaged in their care.17,18

Tips for Bringing Complementary and Integrative Health Into Your Work

As clinicians explore bringing Whole Health approaches into their practices, they often ask about CIH approaches and how they can incorporate them.19 Here are five steps you can consider if you want to build your skills around CIH.

1. Learn about different complementary approaches. Ask your patients about the benefits of these approaches; they are often one your best sources of information about CIH. Why did they choose a particular therapy? What has their experience been? This is not to say that you must agree with them using these therapies. However, being able to offer advice could mean that your patients will be less likely to seek it from less reliable sources, such as various internet sites. It may be most helpful to direct your learning by beginning with the CIH approaches on List One, since these are available to Veterans in the VHA system. (See the IHCC section earlier in this chapter). The Resources section at the end of this chapter has additional information.

2. Know what CIH approaches are offered locally and virtually. Meet the chiropractors at your clinic/hospital if you have not already done so. Is anyone offering acupuncture or Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA)? Are there tai chi or yoga classes available? What online resources do you have? See what is available on the VA Mobile App and Online Tools pages. Are there other facilities that are offering CIH approaches and can partner through telehealth? Is there a mindfulness instructor at your site? What qualifications do local practitioners have? Which practitioners in your community are your patients seeing, and why? Note that OPCC&CT experts such as Field Implementation Team (FIT) consultants are available to help provide guidance, tools, and materials to answer these questions.

3. Build a referral network. As you learn more about complementary approaches and get to know various practitioners, consider building a network of clinicians to whom you would refer. Your facility may have an existing environmental scan or Whole Health directory that lists resources at your site or in your community. Reach out to your Whole Health Point of Contact. Be clear about whether or not your facility allows for referrals to non-VA personnel. Any communication with out-of-system clinicians must be done without any possibility for real or even perceivable gain on the VA clinician’s part, and confidentiality must be respected.

4. Receive treatments yourself. In university settings where fellows are trained in Integrative Health, they are expected as part of their learning to have firsthand experience with various therapies. Want to recommend therapeutic massage to your patients? Try receiving a few different kinds yourself so that you can offer a more informed opinion. Want to be able to knowledgeably discuss acupuncture? See an acupuncturist yourself.

5. If you feel comfortable doing so, learn some CIH approaches to weave into your practice. Many Integrative Health practitioners do this. Some clinicians go so far as to acquire additional certification, but you could also just pick up a few simple techniques you can offer in a short period of time, such as teaching abdominal breathing or leading mindful awareness experiences. Make strategic use of patient handouts to save time. Of course, honor the scope of practice requirements for your particular profession. Also, be respectful of the fact that it can take time and effort to master these techniques.

Classifying Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches

There are many ways of classifying CIH approaches.19 These classification systems have been referred to in the past as “CAM taxonomies.” Sections in the Whole Health Library website draw upon the same taxonomy as was used in the VA’s 2015 HAIG survey.11 This classification scheme is based on one created in the 1990s by the National Center for Complementary Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), which is now the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). NCCIH’s original scheme assigned complementary therapies into five different classes (it has since been changed to just three categories, but to stay consistent with past VA documents, and be more inclusive, the five-category system will be used here):

1. Mind-body medicine. These approaches are covered in Chapter 12, “Power of the Mind.”

2. Biologically-based approaches. These can include nutritional approaches (covered in Chapter 8, “Food & Drink”) as well as dietary supplements, which are discussed in Chapter 15.

3. Manipulative and body-based therapies. Examples of manipulative therapies include chiropractic, osteopathy, and massage (discussed in Chapter 16). Movement therapies in this category (covered in Chapter 5, “Moving the Body”) include yoga, tai chi, and qi gong.

4. Energy medicine therapies (also known as biofield therapies) include Reiki, Healing Touch, and Therapeutic Touch. Biofield therapies are discussed in more detail in Chapter 17.

5. Whole Medical Systems. Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine (of which acupuncture is one component) and naturopathy are examples of healing systems. They have their own unique methods of diagnosis and treatment, based on entirely different concepts of the nature of illness. For more information, refer to Chapter 18.

Just as it can be helpful to consider the self-care circles one-by-one when you are creating a PHP, it can also help to consider each of these CIH categories, one at a time. Which ones, if any, do you think would be useful to a given Veteran? Even if you would not recommend a particular therapy yourself, it is useful to be able to have an informed discussion about them with your patients.

Some of the approaches most commonly used in the VA, or in the U.S. in general, are described in the next four chapters. For biologically-based approaches, the focus will be on supplements. For manipulation and body-based therapies, massage, chiropractic, and osteopathy will be given focus. Energy medicine approaches will be considered as a group, and the whole systems of medicine receiving additional focus will include Chinese medicine and naturopathy, along with a brief mention of Ayurveda and homeopathy. To expand your understanding of these CIH approaches and a wide variety of others, check out the Resources section at the end of each chapter. Again, mind-body approaches are featured in Chapter 12. An even more detailed look at incorporating CIH into practice, “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part III: Complementary and Integrative Health for Veterans” is available on the Whole Health Library website.

Some Key Research Findings for Non-Pharmacological Approaches, By Condition

Table 14-2 lists a variety of health conditions and the non-pharmacologic approaches (in alphabetical order) with the strongest research support.

Table 14-2. Conditions for Which Non-Pharmacologic Approaches Have Particularly Strong Research Support

|

Diagnosis |

CIH Approaches with strong evidence supporting use |

|

Anxiety |

CBT, MBCT, MBSR, Meditation, Music Therapy, Yoga |

|

Cardiovascular Disease |

Meditation, Relaxation Therapies |

|

Depression |

ACT, acupuncture (potentially effective), CBT, Massage Therapy (people with cancer), Meditation, MBSR, Yoga |

|

Fall Prevention |

Tai Chi |

|

Fibromyalgia |

Acupuncture, CBT, Exercise, Hydrotherapy, Mindfulness Meditation, Tai Chi, Myofascial Release |

|

Hypertension |

Biofeedback, Mediation, Tai Chi, Yoga |

|

Insomnia |

CBT-Insomnia, MBSR |

|

Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

Clinical Hypnosis, CBT, Relaxation Exercises |

|

Low Back Pain |

Acupuncture, Exercise, CBT, Massage Therapy, MBSR, Spinal Manipulation, Tai Chi, Yoga |

|

Migraine |

Acupuncture, Biofeedback (including EMG), CBT, Relaxation Therapies, Spinal Manipulation (if tension headache) |

|

Nausea and Vomiting |

Acupuncture |

|

Obesity |

Mindfulness/Meditation, Yoga |

|

Pain, Including Post-Operative |

ACT, Acupuncture (moderate to strong for knee, TMJ, neck), Alexander Technique (neck), Biofeedback, Clinical Hypnosis, CBT, exercise, Guided Imagery, Massage Therapy, Mindfulness/Meditation, Spinal Manipulation (neck), Tai Chi, Dry Needling |

|

PTSD |

CBT, EMDR, Mindfulness/Meditation, Yoga |

|

Substance Use Disorder |

CBT, Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (affects withdrawals and cravings) |

|

Tobacco Dependence |

Acupuncture (possible positive effect), CBT, Mindfulness, Clinical Hypnosis |

ACT = Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; EMDR = Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing; EMG = Electromyogram; MBSR = Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, MBCT = Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy;

This table and its full bibliography can be found on Non-Pharmacologic Approaches to Clinical Conditions. A more comprehensive Library of Research Articles on Veterans and CIH Therapies is also available on the VA website.[906]

Complementary and Integrative Health Resources

Websites

VA Whole Health and Related Sites

- A Glimpse Into Integrative Health. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zl9p27Ih_DY&index=5&list=UUaW28mX6gCpTuWYJyPfWd-Q

- IHCC SharePoint. Has document libraries for all of the different CIH approaches. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/professional-resources/IHCC.asp

- CIH Resource Guide. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/VHAOPCC/Shared%20Documents/Forms/AllItems.aspx?FolderCTID=0x012000965D235B81AE9A40B070A146F202ECC1&View=%7B4BA2C7D3%2DD49A%2D456C%2DA49A%2DB6B2153C997B%7D&id=%2Fsites%2FVHAOPCC%2FShared%20Documents%2FCIH%20Resource%20Guide%2FCIH%20Resource%20Guide%5FFinal%5FAug2019%2Epdf&parent=%2Fsites%2FVHAOPCC%2FShared%20Documents%2FCIH%20Resource%20Guide

- Policy Folder.

- https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/professional-resources/IHCC.asp

- Position Descriptions.

- https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/VHAOPCC/Shared%20Documents/Forms/AllItems.aspx?RootFolder=/sites/VHAOPCC/Shared%20Documents/CIH%20Position%20Descriptions%20and%20Functional%20Statements&FolderCTID=0x01200092D5EAC253479641B8D0A20FE4165E94&View=%7b4AD754A9-57D5-4A13-A317-D62DAB4881EB%7d

- Whole Health System Coding and Tracking Guidance. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-resources/MobileApps-OnlineTools.asp

- Standard Episodes of Care (SEOCs). For various CIH approaches in VA. https://seoc.va.gov/

- TeleWholeHealth Resources. https://telehealth.va.gov/type/clinic

- VA Mobile Apps and Online Tools. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-resources/MobileApps-OnlineTools.asp

- CIH Listservs. To be added, contact:

- Any listerv: Lana Frankenfield Lana.Frankenfield@va.gov

- Acupuncture listerv: vhava-bfa-community@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Biofeedback listerv: vhabiofeedback-cop@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Clinical Hypnosis listerv: vhahypnosis@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Guided Imagery listerv: vhaguided-imagery-community@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Massage Therapy listerv: vhamassage@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Meditation listerv: vhameditation-community@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Tai Chi and Qi Gong listerv: vhatai-chi-community-of-practice@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- Yoga listerv: vhava-yoga@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- National CIH Subject Matter Experts, as of FY 2020.

- Acupuncture: Juli Olson Juli.Olson@va.gov

- Biofeedback: David Gaffney David.Gaffney@va.gov

- Chiropractic: Anthony Lisi Anthony.Lisi@va.gov

- Clinical Hypnosis: David Gaffney David.Gaffney@va.gov

- Guided Imagery: David Gaffney David.Gaffney@va.gov

- Massage Therapy: Sharon Weinstein Sharon.Weinstein@va.gov

- Meditation: Kavitha Reddy Kavitha.Reddy@va.gov, or Alison Whitehead Alison.Whitehead@va.gov

- Tai Chi/Qi Gong: Kavitha Reddy Kavitha.Reddy@va.gov, or Alison Whitehead Alison.Whitehead@va.gov

- Yoga: Alison Whitehead Alison.Whitehead@va.gov

- Important Email Addresses.

- For national CIH program/policy questions contact

- For course related questions, email the WH Education Team wheducation@DVAGOV.onmicrosoft.com

- For CIH Field Implementation Questions contact VHAOPCCCTCIHSpecialtyTeam@va.gov

- For Whole Health and CIH Tracking and Coding Questions contact

- VHAOPCC&CTWHSTrackingTeam@va.gov

- Evidence Maps. Compilation of systematic review data by VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D). https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/reports.cfm

- Evidence Map of Acupuncture. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/acupuncture.cfm

- Evidence Map of Guided Imagery, Biofeedback, and Hypnosis. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/management_briefs/default.cfm?ManagementBriefsMenu=eBrief-no153&eBriefTitle=Guided+Imagery%2C+Biofeedback%2C+and+Hypnosis

- Evidence Map of Massage for Pain. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/massage.cfm

- Evidence Map of Mindfulness. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/cam_mindfulness.cfm

- Evidence Map of Tai Chi. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/taichi.cfm

- Evidence Map of Yoga for High-Impact Conditions Affecting Veterans. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/yoga.cfm

- Evidence Map of Aromatherapy and Essential Oils. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/aromatherapy.cfm

- Evidence Map of Art Therapy. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/art-therapy.cfm

- Giannitrapani et al. Synthesizing the Strength of the Evidence of Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies for Pain. Pain Medicine. 2019. Excellent evidence map for pain and CIH (not from HSR&D). https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/20/9/1831/5487508

- VHA Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. VA Publications. https://vaww.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5401

- Whole Health System of Care Evaluation: A Progress Report on Outcomes of the WHS pilot at 18 flagship sites. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCCWholeHealthSystemofCareEvaluation-2020-02-18FINAL_508.pdf

- Courses that offer continuing education credits are available through TMS and TRAIN. Courses include: Clinician Self-Care: You in the Center of the Circle of Health (VA TMS Item Number: 29697); An Introduction to Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches (VA TMS Item Number: 29890); Eating for Whole Health: Introduction to Functional Nutrition (VA TMS Item Number 34592); and Mindful Awareness (VA TMS Item Number: 31300). Site has complete description of these courses as well as the TMS and TRAIN ID Numbers. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/VHAOPCC/Whole%20Health%20Online%20Modules/Forms/AllItems.aspx

Whole Health Library Website

- Whole Health Library. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu

- Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part III: Complementary and Integrative Health for Veterans. Overview.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/overviews/part-iii-complementary-integrative-health/

- Complementary Approaches in the VA: A Glossary of Therapies and Related Whole Health Resources Where You Can learn More.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/complementary-approaches-glossary/

- Savvy about Complementary and Integrative Health: The “CIH” Quiz. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/savvy-about-complementary-integrative-health

- Non-Pharmacologic Approaches to Clinical Conditions. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/tools/non-pharmacologic-approaches-to-clinical-conditions/

- Personal Health Plan Template. https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/414/2018/08/Brief-Personal-Health-Plan-Template.pdf

- Integrative Pain Management Series 10 Hours.

- https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/online_courses/pain_series.html

- Whole Health courses

- Whole Health Partner.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/whole-health-partner/

- Whole Health in Your Practice.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/whole-health-in-your-practice/

- Whole Health for Pain and Suffering: An Integrative Approach.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/whole-health-for-pain-and-suffering/

- Eating for Whole Health: Nutrition for all Clinicians.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/eating-for-whole-health/

- Taking Charge of My Life and Health.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/whole-health-facilitated-groups/

- Whole Health Coaching.

- https://wholehealth.wisc.edu/courses-training/whole-health-coaching/

Other Websites

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). https://nccih.nih.gov

- Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health (ACIMH). https://www.imconsortium.org

- Integrative Medicine Board Certification Eligibility Requirements. American Board of Physician Specialists. http://www.abpsus.org/integrative-medicine-requirements

- Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine health resources. https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/resources.html

- University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Integrative Medicine Resources. www.fammed.wisc.edu/integrative

Books

- A Guide to Evidence-Based Integrative and Complementary Medicine, Vicki Kotsirilos (2011)

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Legal Boundaries and Regulatory Perspectives, Michael Cohen (2008)

- Complementary and Integrative Medicine in Pain Management, Michael Weintraub (2008)

- Essentials of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Marc Micozzi (2015)

- General Practice: The Integrative Approach, Karryn Phelps (2011)

- Integrative Cardiology, John Vogel (2007)

- Integrative Medicine, 4th edition, David Rakel (2017)

- Integrative Medicine Library, Andrew Weil. There are multiple titles, including:

- Integrative Addiction and Recovery, Shahla Modir (2018)

- Integrative Cardiology, Stephen Devries, (2010)

- Integrative Dermatology, Robert Norman (2014)

- Integrative Environmental Medicine, Aly Cohen, (2017)

- Integrative Gastroenterology, Gerard Mullin (2011)

- Integrative Geriatric Medicine, Mikhail Kogan (2017)

- Integrative Men’s Health, Myles Spar (2014)

- Integrative Nursing, Mary Jo Kreitzer (2014)

- Integrative Oncology, 2nd edition, Donald Abrams (2014)

- Integrative Pain Management, Robert Bonakdar (2016)

- Integrative Pediatrics, Timothy Culbert (2009)

- Integrative Preventive Medicine, Richard Carmona (2017)

- Integrative Psychiatry and Brain Health, Daniel Monti (2018)

- Integrative Rheumatology, Randy Horowitz (2010)

- Integrative Sexual Health, Barbara Bartlik (2018)

- Integrative Women’s Health, 2nd edition, Victoria Maizes (2015)

- Integrative Oncology, Maurie Markman (2008)

- Integrative Pain Medicine, Joseph Audette (2008)

- Textbook of Integrative Mental Health Care, James Lake (2006)

- The Duke Encyclopedia of New Medicine, Duke Integrative Medicine (2006)

Journals (not an exhaustive list)

- Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine

- BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice

- Complementary Therapies in Medicine

- Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing

- Global Advances in Health and Medicine

- Integrative Cancer Therapies

- Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal

- Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine

- Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine

Special thanks to Kavitha Reddy, MD and Alison Whitehead, MPH, RYT, PMP, who provided content for this chapter based on their work for the VA IHCC, as well as Aysha Sayeed, MD, who also reviewed it as a National Education Champion for OPCC&CT.