Passport to Whole Health: Chapter 19

Chapter 19. Whole Health and Community

If we want a beloved community, we must stand for justice, have recognition for difference without attaching differences to privilege.

―Bell HooksCommunity is where humility and glory touch.

–Henri J.M. Nouwen

The Importance of Community

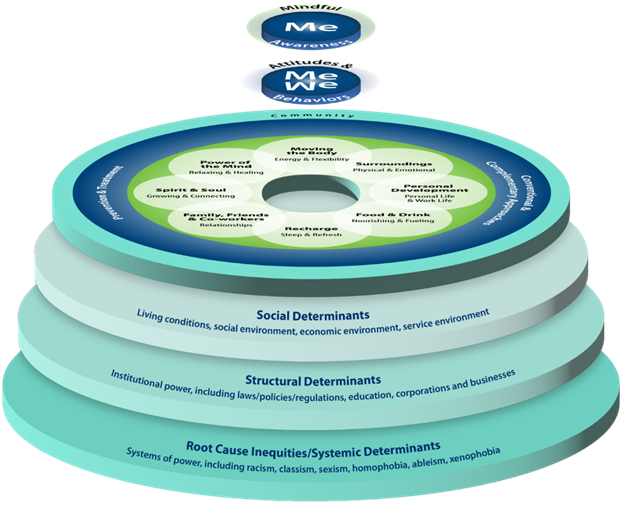

Encompassing all of the other areas within the Circle of Health is the outermost circle, Community. All elements of Whole Health—including “Me” at the center, self-care, and professional care—happen within the context of and uniqueness of a larger community. The Community circle encompasses and underlies all the others; community is fundamentally important to all aspects of health and well-being. It is the largest ring in the Circle of Health for a reason—it has global impact.

Community refers to the spaces in which we live, the resources we have available to us day-to-day, and our relationships with others in our broader environment. Community includes our culture, our social systems, our history, and our geography. It is the larger framework in which health is supported or, conversely, challenged. Health does not start in the VA (though VA certainly makes important contributions); it starts in our homes, our schools, our workplaces, and our neighborhoods.

One person may be a member of many communities for many reasons. Some examples include:

- Upbringing: family networks, spiritual practices or groups, childhood experiences (adverse or not)

- Interests: professional pursuits, activities, or clubs

- Location: neighborhood, local communities, cities, counties, regions, nations, and other geographical cultures

Attributes: Race/ethnicity, ability level, gender-orientation, etc.

Attributes: Race/ethnicity, ability level, gender-orientation, etc.

Our relationship with the people, places, and resources in our communities shape how we perceive ourselves and the world around us. As noted in Figure 19-1, personal identity, or “Me,” is often understood through the reflection of community, or “We.”

![]() Without the “We” aspect of healing, Whole Health—and all health care—would be very limited. The health of one’s community is essential to the promotion of health for those within it. Community shapes our ability to engage in healthy behaviors and pursue what matters to us.

Without the “We” aspect of healing, Whole Health—and all health care—would be very limited. The health of one’s community is essential to the promotion of health for those within it. Community shapes our ability to engage in healthy behaviors and pursue what matters to us.

It adds to the richness of the Whole Health approach if we move through the different components of the Circle of Health once more, this time looking at them through the lens of Community.

Me: Individualizing Care Through Understanding Context

Conventional care often focuses on the individual, exploring what is going wrong inside the body. This is important, but people do not exist in a vacuum; the behaviors of the molecules inside our body are affected by all sorts of things outside of us. “Personal identity” is actually defined by how we define ourselves in relationship to the communities of which we are part. Even focusing just on the innermost “Me” in the center of the Circle of Health, we begin to see how strongly influenced we are as individuals by our context. Certainly, when a person is asked, “What really matters to you?” they will frequently respond that it is the others in their lives who matter most.[1272] Our different communities—and the beliefs, values, and norms we gain from these communities—strongly influence our Mission, Aspiration, Purpose (MAP).

Part of individualizing care is being aware of context, all the factors that shape a person’s life and what matters to them.[1273] It is not essential that we know every detail about our patients’ histories, their value systems, or their day-to-day lives, but it is important that we remain open to considering, understanding, and appreciating those factors. To achieve health equity—or the attainment of the highest level of health for all people—requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contempory injustices, and the elimination of health and health care inequities.

Consider the many different ways one’s relationship within Community can affect how they engage in their health care. Take this example describing two Veterans, each of whom presents for a primary care appointment in the VA.

- The first Veteran arrives early and is accompanied by a family member, having driven from home nearby. The Veteran is retired and service-connected, and he schedules his appointments around his personal travel schedule. He has had good relationships with VA staff in the past, and he enjoys volunteering with a Veteran Service Organization.

- The second Veteran arrives a few minutes late because the second bus he took to get to the VA was running slow. He has no family support and is struggling to pay his bills. He is concerned that he will be charged a co-pay for this and future appointments. He has avoided care because he has felt discriminated against in the past due to his sexual orientation. He feels marginalized in the Veteran community.

Imagine how different these Veterans’ appointments could end up being. Each Veteran is likely to perceive health care in very different ways, experience different levels of trust with staff, and differ in their willingness to partner on health goals. These contextual factors have as much impact on their engagement with and desire to follow a Personal Health Plan (PHP) as any of our health care recommendations. And as we will see, these factors impact Veteran experiences in all other areas of health as well.

The following is a small sample of context-related questions you may ask yourself about each of the patients you serve, to more effectively support them as they set shared and SMART goals:

- Does the Veteran have access to a given therapy or practitioner? Do they have transportation? Is there a long wait to schedule a visit?

- Can they afford the therapy, or is it financially covered in some other way?

- Do they have the skills or health literacy to follow through with the plan?

- Do their various illnesses prevent them from achieving their goals? (For example, substance use disorder, severe mental illness, and/or dementia can be significant impediments to success.)

- Can someone else help this person keep track of their schedule, get to their appointments, or offer them moral support?

- Consider how social determinants of health (SDOH) impact the Veteran. Does the Veteran belong to a group or demographic that makes them more likely to have poorer health?

- How are the Veteran’s care options affected by social policy, law, and how the health care system functions in general?

- Do cultural, religious, and other factors have the potential to support healing or interfere with it?

- Is the PHP taking into account what they have already tried?

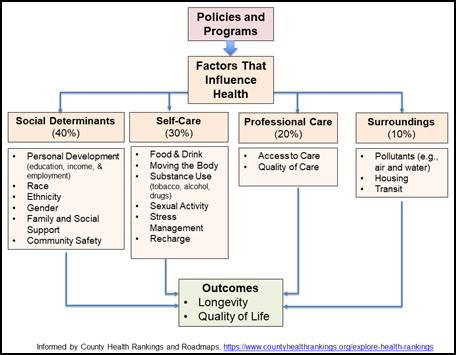

It can help to have a sense of various facts about SDOH as you consider those questions. As defined by the US Department of Health & Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (DPHP), SDOH are defined as “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”71 Examples include availability of resources, access to educational and job opportunities, transportation, education quality, public safety, social support, norms and attitudes (e.g., racism, trust of the government), segregation, language, literacy, access to technology, culture, and availability of health care and community-based resources. By understanding how to address social and structural determinaints of health, you are better equipped to learn the whole story about the Veterans you serve. What if we tipped the Circle of Health on its side and looked underneath? That’s where we find social, structural, and systemic determinants of health.

While medical training recognizes the Whole Health approach, and is driven by “do no harm”, emerging practice that follows the research realizes the limitations to that original medical model alone. Whole Health builds on this understanding of the interconnectedness of health factors and it opens the door to discuss not only Veterans’ health conditions that can be captured by diagnostic codes, but the conditions that impact both their health and well-being.

Attunement to context has a significant impact on quality of care and prevents medical errors.2 It reconnects us to Whole Person care. There are some striking parallels between how the Whole Health approach can emphasize a person’s connecting with community and how the Recovery Model also does this in mental health.[1274]

Research suggests that an individual’s health is heavily influenced by their community and its impact on the individual’s behavior.72 In fact, this recognized and validated model from the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute demonstrates that of the factors we can control to shape health, 80% of health outcomes are determined by social and economic, environmental, and behavioral factors.69 The following examples provide more information about how SDOH factor into healthcare practices. In a 2019 VHA survey of nearly 44,000 Veterans, those with earnings of less than $35,000 a year reported poorer overall physical and mental health, noted they received lower levels of social and emotional support, and said they were less likely to feel they had a purposeful and meaningful life.73 Additionally, those making less than $35,000 are three times more likely to smoke, have higher rates of obesity, and are less likely to meet guideline-recommended levels of physical activity compared to other adults. 73 Income and economic stability are arguably some of the most important social determinants of health. People with steady employment are less likely to live in poverty and more likely to be healthy, but many people have trouble finding and keeping jobs.74 Further, economic stability is often determined by employment which drives income and access to benefits for retirement savings, health insurance, and the ability to pay for basic necessities such as nutritious food, housing, childcare, healthcare, and transportation.74 People with disabilities, injuries, or conditions like arthritis may be especially limited in their ability to work.71

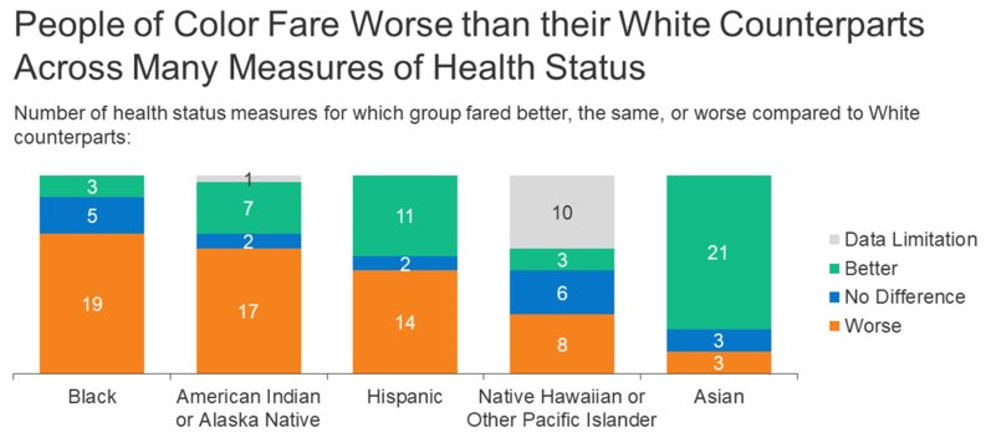

Beyond economic stability, gender, race, class, disability status, and sexual orientation are very influential social determinants of health. 63% of American adults report experiencing discrimination every day.75 Sexual and Gender Minority (SGM) Veterans are disproportionately discriminated against. Being a member of both Veteran and SGM communities may contribute to a higher level of risk for poor health than membership in just one of these populations. Dual health disparities arising from two identities are clearly demonstrated when observed separately, yet there is a limited understanding as Elevated health problems and barriers to healthcare access have also been documented within the transgender community, including high rates of discrimination, trauma exposure, and suicide ideation.70 25% of SGM Veterans report avoiding VA services due to stigma.70 Stigma often prevents patients from seeking or receiving proper medical care. Women are diagnosed at a much higher frequency than men in the VA with musculoskeletal conditions and mental health diagnoses.71 In addition, racial disparities are clearly present in the VA, just as they are in the rest of the country.77 Recent data from the CDC shows that people of color fare worse compared to their White counterparts across a range of health measures, including infant mortality, pregnancy-related deaths, prevalence of chronic conditions, HIV/AIDS diagnosis, overall physical and mental health status, and death rates.78 As of 2018, life expectancy among African American people was four years lower than White people, with the lowest expectancy among Black men.70 Research also documents disparities across other factors; for example, low-income people report worse health status than higher income individuals and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) individuals experience certain health challenges at increased rates.79

Intersectionality refers to the overlap and interaction of different categories of social identities and related structures of oppression and discrimination.80 Some researchers describe intersectionality as a way of understanding and analyzing complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences.81 The events and conditions of social and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor; they are shaped by many factors in diverse and mutually influencing ways. When it comes to social inequality, people’s lives and the organization of power in a given society are better understood as being shaped not by a single axis of social division, be it race or gender or class, but by many axes that work together and influence each other.74 Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the complexity of the world and of themselves.73

Attunement to context and cultural humility can have a significant impact on quality of care and prevents medical errors.82 It reconnects us to Whole Person care. There are some striking parallels between how the Whole Health approach can emphasize a person’s connecting with community and how the Recovery Model also does this in mental health.

As this discussion about Community applies to our patients, so too does it apply to clinicians. We bring our own experiences, our culture, our stressors, our values, and our assumptions into our therapeutic relationships. We can be more effective healers when we acknowledge the unique attributes we bring to our relationships with Veterans.

Mindful Awareness: Noticing Judgments and Biases

Cultural Humility. “To practice cultural humility is to maintain a willingness to suspend what you know, or what you think you know, about a person based on generalizations about their culture. Rather, what you learn about your clients culture stems from being open to what they themselves have determined is their personal experience of their heritage and culture.” -Moncho, 2013

- Approaching Veterans with cultural awareness and humility requires that practitioners be humble about their level of knowledge about a Veteran’s beliefs or values, be aware of their own personal assumptions and the inherent power imbalance in a patient-provider relationship, and aim to treat the whole person by learning about their background.

Veteran Considerations. In terms of the Veteran perspective related to Community and mindful awareness, consider the following:

- People are more than the demographic groups to which they belong; be careful not to make assumptions about whether or not someone will resonate with cultivating mindful awareness based on their age, race, gender, or other characteristics. As always, explore the needs and preferences of each individual.

- Whether research is available or not, you can always do an “N of 1” trial. That is, have a person try an approach to being more mindful and see if it makes a difference specifically for them.

- Mindfulness awareness cultivates the capacity to be with an experience as it is with an open heart. While mindfulness is not a cure-all and cannot change the circumstances people face in their communities, a greater awareness can result in skillful responses to stressors and even more systemic change.

Mindful Awareness and Diversity. Beneath the Circle of Health, we find social, structural, and systemic determinants of health. While medical training recognizes the Whole Health approach and is driven by the idea, “do no harm,” emerging practice that follows the research realizes the limitations to that original medical model alone. Whole Health builds on this understanding of interconnectedness of health factors and it opens the door to discuss not only Veterans’ health conditions that can be captured by diagnostic codes, but the conditions that impact both their health and well-being.

There is room for expansion when it comes to research about mindfulness focused on diverse populations. A 2018 systematic review noted that most of the research focuses, as much of the complementary and integrative health (CIH) research does, on “middle-to-upper class, Caucasian women.”[1275] A 2019 narrative review, which it should be noted was not peer-reviewed,[1276] found the following when it focused on research for different demographic groups:

- Age. Most studies are on middle-aged adults, but results are also promising for younger and elderly populations. Studies involving adolescents have inconsistent findings.

- Disability. Tailored mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) seem to improve quality of life, behaviors, and emotion regulation in people with developmental disabilities. Of note, most studies focus on participants who are fairly high functioning. MBIs seem to benefit well-being in people with acquired disabilities as well and may help slow loss of cognitive function for some disorders.

- Race / Ethnicity. Increasing numbers of studies focus on mindfulness for people of color. A number of small studies involving African Americans, Asian Americans and Hispanic people have shown promise. Mindfulness has been found to serve as a buffer for discrimination-related distress.

- Gender. Men are underrepresented in mindfulness research. In general, women appear to derive more benefit according to some emotional measures. Trans*, non-binary, and agender people have not been the focus of much study thus far.

- Religion. In the West, mindfulness practice is primarily secular. One study found that in African American college students, there was an association between religiosity and a higher level of mindfulness. Most studies focus on people who are white and Christian.

- Sexual orientation. A relatively small number of studies indicates that MBIs may influence self-esteem and stress tolerance in LGBTQIA+ individuals. In addition, recent research suggests that mindfulness practices can decrease feelings of isolation in the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Socioeconomic status. Studying the effects of mindfulness training on low-income groups can be complicated by feasibility issues (e.g., people are working multiple jobs and cannot come to classes). Research is promising but limited.

It is worth noting, however that MBIs offered to diverse clinical Veteran populations do suggest that these interventions are effective in Veteran populations.[1277],[1278],[1279],[1280],[1281],[1282] There is also literature on people incarcerated and working in prisons,[1283] with people who are homeless,[1284] and beyond, suggesting mindfulness can be helpful to a broad range of people. More research is needed, and it would seem that MBIs have the potential to benefit a diverse array of people.

Clinicians, Community, and Mindful Awareness. Implicit biases are unconscious associations we make that lead to negative evaluations of a person on the basis of characteristics such as race, genderage, body size, ability, etc. These are in contrast to explicit, or conscious biases. A 2017 review of 42 articles focused on health care professionals found that they exhibit the same (strikingly high) levels of implicit bias as the wider population.[1285] These biases are strong enough to be likely to “influence diagnosis and treatment decisions and levels of care in some circumstances...” For example, a 2015 review of 15 studies concluded, “Most health care providers appear to have implicit bias in terms of positive attitudes toward Whites and negative attitudes toward people of color.”[1286] The authors noted this may contribute to health disparities. A 2017 review noted that physicians, regardless of specialty, display preference for white people, but noted no indication that this had an impact on medical decision making.[1287] Nurses show similar biases,[1288] as do mental health professionals.[1289] Implicit biases also exist around gender,[1290] body weight,[1291] age,[1292] sexual orientation,[1293] and many other patient characteristics.

Fortunately, awareness of these biases may decrease their contribution to health disparities. A 2014 Cochrane review concluded that there is positive (though low-quality) evidence indicating that cultural competence education can lead to a higher likelihood that health care professionals will involve culturally and linguistically diverse patients in their own care.[1294] Practicing perspective taking and focusing on the individual uniqueness can negate or reduce the negative effects of biases.[1295]

It has been proposed that mindful awareness may help to mitigate or unseat implicit biases, and while this is a fledgling field of research, results so far have been promising. A 2014 study found that mindfulness meditation (10-minutes, mostly focused on breath and a body scan) decreases implicit race and age bias.[1296] A 2016 study found that participants who listened to a 10-minute mindfulness audio recording prior to a game-based interaction with a variety of other people were also less likely to show age- or race-based biases.[1297]

Of course, being aware of and working with explicit biases is also key.[1298] These biases occur as the result of deliberate thought and thus can be regulated consciously. Meeting people about whom one has explicit biases can help to decrease them. Loving-kindness meditation decreases implicit bias[1299]—and biases in general—when practiced regularly.[1300] The goal of “heart-centered” meditations is to enhance kindness and compassion toward others in any number of ways. Chapter 10 features a loving-kindness meditation.

Social Determinants of Health and Self-Care: How Community Ties to Health Behaviors

As noted above, the DPHP’s Healthy People 2020 Initiative defines SDOH as the social and physical environments that impact a person’s health.Error! Bookmark not defined. Five key areas of SDOH include: 1) Economic Stability, 2) Education, 3) Social and Community Context, 4) Health and Health Care, and 5) Neighborhood and Built Environment. Social, physical, and economic conditions are examples of SDOH, as are social engagement, access to resources, and security. Unfortunately, social risks seem to cluster among the same people and accumulate for them over time.[1301] The Midcourse Review on DPHP website offers a snapshot of how the U.S. is doing with regard to a number of national health indicators. A 2019 article featured a suggested lexicon for SDOH to help foster a common language and decrease misunderstandings.[1302] o truly be holistic in its scope, a Whole Health system focuses on bringing SDOH into the health care partnership and PHP process. Strategies for reducing the negative effects (and enhancing positive ones) related to SDOH can have a profound impact.[1303] Figure 19-2 links SDOH to health outcomes, putting their influences into context with other factors that also influence length and quality of people’s lives. Note that only 20% of health outcomes are attributable to Professional Care; the other 80% are tied to social, economic, environmental, and behavioral factors.[1304] Asking about these other aspects of health can potentially enhance Veterans’ (and everyone’s) Whole Health.

Each of the eight areas of self-care is influenced by—and influences—Community in different ways. What follows are some examples related to each one. For more information, go to the specific chapters about each of these different areas (Chapters 5-12).

Moving the Body

- Neighborhood safety, sidewalks, lighting, and accessibility features influence people’s options to walk, move, or exercise outside.

- Community green spaces and parks promote physical activity.

- Financial resources influence people’s abilities to buy gym memberships, purchase exercise equipment, and engage in organized recreational activities.

Surroundings

- Health hazards such as mold, infestations, lead contamination, poor air quality, and allergens are much more likely to be found in low-income housing.

- Low-income and minority populations have increased risk for pollution exposure, which affects health outcomes.

- Living near a park is associated with lower obesity and other favorable health outcomes.

- Better public transportation is linked to better attendance of medical appointments.

- Members of segregated communities have higher infant mortality rates and poorer mental health.[1305]

- Crime and safety make a huge difference, and so does one’s current or past experience with incarceration.

- Accessibility (ramps, benches, sidewalks, etc.) plays a huge role in people being able engage with their surroundings.[1306]

Personal Development

- A lack of educational opportunities has long-lasting negative consequences, including reduced earning potential.

- Without education and rewarding, stable employment, people are often ill-equipped to make healthy choices. Every year of education a person has is tied to even better health outcomes and behaviors.68

- Discrimination in the workplace has negative health effects, such as increased blood pressure, heart rate, and stress levels, as well as decreased self-efficacy.68

Food and Drink

- 40 million Americans experience food insecurity, meaning their access to adequate food is limited by a lack of money or other resources.[1307] People of color are disproportionately affected.

- Food insecurity is linked to a higher likelihood of a number of health problems, including, for women, being overweight.[1308]

- Alcohol,[1309] smoking,[1310] and other substance use disorders[1311] are more common among people who have markers of social and economic disadvantage, such as poverty, severe mental illness, or less than a high school education.

Recharge

- Home is an important place to recharge, and it can be compromised when one lacks decent, safe housing.

- Socioeconomic status affects a person’s ability to pursue leisure activities and hobbies.

- Crowded and/or noisy living conditions can limit one’s ability to find solitude or be recharged.

Family, Friends, and Co-Workers

- Social networks have s significant influence on beliefs and behaviors, both in positive and negative ways.

- Social standing impacts opportunities we are afforded and our own self-efficacy.

- Loneliness and low community involvement have a huge impact on morbidity and mortality.

Spirit and Soul

- Faith-based organizations can help inform people about prevention, promote healthy behaviors, and link people to prevention resources through programs and partnerships. They can also promote safer and more connected communities, preventing injury and violence.

- Places of worship can also provide space for organized pro-social activities.

Power of the Mind

- Repeated and prolonged exposure to systemic environmental and social stress activates our sympathetic nervous systems, which increases risk of chronic disease.

- Social risks can be important drivers of suicide, and interventions focused on community engagement and public health actions show promise.[1312],[1313]

For an excellent compendium of research findings related to these different areas, go to the Healthy People 2020 or Centers for Disease Control websites.

Professional Care: Healthy Health Care Communities

Professional Care only succeeds in a community if it is of good quality and if people have access to it. It takes a village to do Whole Health. That village includes health care providers and other clinical team members, as well as staff, a patient’s loved ones, and the patient. It also includes practitioners of various CIH approaches; access to these services varies greatly from one community to the next, and resources like Telehealth can help to remove some of the disparities with access.

When we talk about Whole Health, the scenario that comes to mind first for some people is a clinical, or one-on-one, encounter. A patient (Veteran, clinician, etc.), perhaps with loved ones, visits with a clinician, or perhaps several members of a team, and co-creates (or elaborates upon) a PHP that supports MAP. However, beyond the one-on-one efforts, care becomes most effective when we can integrate community into it.

Caring communities of all sizes. Whole Health services can be provided to multiple people at once, in a class or as part of a shared medical appointment. Whole Health is happening when a facility’s Whole Health Committee plans a hospital-wide event, or when a group of nurses in a clinic decide to walk together at lunch. It also happens when different clinical areas or disciplines partner to better integrate care efforts. It happens in fitness centers, neighborhood parks, VFW buildings, workplaces, places of worship, and even the canteen at the local VA hospital. It happens when a Whole Health Partner or Coach connects a Veteran with a community resource that supports them with attaining a shared goal. It might look very different to different people.

Policy makers, public health officials, pentad members, and administrative people may have a different but, of course, no less important role in moving Whole Health forward in their facilities and local communities. Without leadership and frontline staff, Whole Health cannot fulfill its maximal potential.

Leadership and advocacy. Buy-in from leaders makes all the difference in terms of whether or not clinicians, Whole Health Partners, Whole Health Coaches, and others can fully offer their expertise. Meeting with leaders in your facility is as important to promoting Whole Health is as talking to a patient about healthy behaviors; that is, both are extremely important. If something is not going well, or if obstacles are compromising your ability to offer Whole Health, seek help and support. Write your Congressperson. Talk to your supervisor. Step up on behalf of your Veterans. Engaging in behaviors such as voting, getting involved in your local community, and working with medical advocacy organizations to practice social responsibility.

Program evaluation. Many people shy away from quality improvement efforts, but asking what can be done to improve programming, or to evaluate how a program is doing in terms of outcomes measures, can weave in community resources and contribute to an environment more supportive of Whole Health.

Engagement and partnerships. A powerful ally on the team is a social worker or someone else versed in what programs, classes, and support mechanisms are available not only in the VA, but at the community, county, state, and national level. There are many communities that have programs where volunteers offer free or discounted services specifically for Veterans, such as acupuncture, yoga classes, or even house cleaning services. Your VA Medical Center’s Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Program Manager is another good resource for VA and community programs and resources. A link to a full directory of Veterans and Military Service Organizations is featured at the end of this chapter. The VA website features information about Community Care Networks, particularly important now as the MISSION Act has gone into effect. Partnering with the VA Office of Health Equity can also be extremely useful, and it may help to promote non-clinical services that may help to address SDOH deficits, such as Vocational Rehabilitation, and Recreational Therapy. They offer a number of resources, including fact sheets, learning series, and local data that can be useful to Veterans and health care professionals alike.

Beyond Self-Care and Professional Care: The Community at Large

In the highly varied and numerous communities in which we live, there are multiple complex systems that influence the health of individuals in all those systems. The following larger-scale influences on Whole Health might not be mentioned explicitly in a clinician-patient encounter also have a profound influence:

Public health. Each of us benefits from measures to contain diseases like tuberculosis, or to vaccinate against diseases that would otherwise harm entire populations of people. For example, smoke-free laws for bars, restaurants, and workplaces reduced hospitalizations by 8-17% in a year.[1314]

Policy. Laws exist to keep people safe in any number of ways. It is possible to discuss the Whole Health approach because of legislation, funding, and support from leaders at the national, VISN, and local leadership levels.

Environment at the ecosystem level and beyond. At the largest-scale level, we belong to the community of humanity and the community of life on earth. There is no doubt that decisions on the other side of the planet can influence our day-to-day experiences of our world. Pollution is a community issue. Global warming is a community issue with the potential to negatively affect health in a profound way.[1315] How environmentally friendly, or “green,” our health care facilities is a community issue. All of these affect individual health too.

Culture. People belonging to a given culture are unique, but cultural standards and norms do influence perspectives on health. Being part of an ethnic group, following various traditions, and the influences of one’s family of origin can all inform health care behaviors and preferences. Practicing with cultural humility is essential.[1316],[1317] Cultural humility is our “ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the person.”45 Cultural humility informs care of people who may be different from a care team member in terms of factors such as race, ethnicity, social status, sexual preferences, and professional roles.[1318] Cultivating cultural humility is a lifelong process, built around openness, self-awareness, egolessness, self-evaluation, and supportive interactions. Humble care team members are more effective at patient care.[1319] More information is available in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

Equity and social justice. Tragically, poverty, race, educational status, and other such measures are all linked to morbidity and mortality.[1320],[1321] Programs to improve a Veteran’s situation in such areas make an important difference. In the U.S., the income for the wealthiest 1% of the population has doubled, even as the poverty rate has held steady.[1322],[1323],[1324] According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, White and Asian wages remain over 30% higher than wages for Blacks or Latinos.51,[1325] The more equitably wealth is distributed in a country, the higher the average life expectancy51 and the lower the infant mortality and heart failure rates.[1326],[1327] People live longer based on equitable resource distribution at a state level as well.[1328] Not surprisingly, people with lower incomes are more likely to die of cancer, be obese, smoke, and have more stressful lives.51

Wise use of resources. The U.S. is the only country in the “developed world” that spends more of its gross domestic product on health care than on social services.[1329] Consider these statistics:

- The U.S. spends more on health care than any other country, but our life expectancy and overall health rate lower than many other countries’.58

- U.S. clinicians order many more diagnostic tests than most countries,[1330] and many of these tests are not needed to determine care outcomes.[1331]

- Americans visit the doctor fewer times per year than people in most other countries (especially the wealthier ones), but care is still much more expensive.

- A 2003 study concluded that adults living in 12 metropolitan areas in the U.S. only received about 55% of the medical care that was recommended for them.[1332]

- In 2011, one-third of American households said they had trouble paying their medical bills.[1333]

- 165,000 Americans died due to overdoses of prescription opioids between 1999 and 2014.[1334] Meanwhile, 83% of the world’s population has no access to opioid pain medications, largely because they are all being consumed in the U.S.[1335]

- Lack of insurance is, unsurprisingly, linked to poorer care, poorer health status, and premature death.[1336]

Examples of SDOH-Related Projects

A number of sites have reported on programs they have been using to bring SDOH into care. Some important examples include:

- Addressing Circumstances and Offering Veteran Resources for Needs (ACORN). This VISN1 program is offered in primary care. A SDOH screener asks questions about items such as food insecurity and transportation needs. Veterans answer the questions on a tablet, and data instantly loads into the medical record. People with positive screens receive a geographically tailored resource guide with both VA and non-VA resource suggestions. The group reports that the most common needs they see are related to social isolation (50%), employment assistance (36%), and personal safety (16%).

- Pro-Active, Recovery-oriented Treatment Navigation to Engage Racially Diverse Veterans in Mental Healthcare (PARTNER-MH). The Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis runs this peer-led patient-navigation program for minority Veterans in an outpatient mental health clinic. The program provides screening, navigation, peer support, and other assistance using a SDOH framework to 1) engage Veterans in mental health services, 2) activate Veterans to become active partners in their care, and 3) improve their participation in shared decision making with their mental health care providers.

- Be Connected.[1337] This program enlists a web of community support to help reduce Veteran deaths by suicide with three components they refer to as Call, Match, and Learn. The 24/7 Be Connected Call Program offers access to a support line. The Match program links Veterans and their families to different resources. The Learn program trains VA and community providers, including first responders and legal professionals around building networks of care, services, and support.

- Joining Hands, Feeding Veterans.[1338] This program, offered by the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, works to address food insecurity, noting that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the food stamp program) doesn’t always fully meet people’s needs. The VA system partnered with the Central Texas Food Bank and has provided food to over 400 Veteran households in Austin and Temple. The project involves mobile food pantries and brings together an array of food suppliers and financial donors in the region.

Engaging in our local communities, as well as at the larger state, national, and even global levels can bring Whole Health to all levels of care. Clinicians can bring awareness to these different levels, and Veterans must do so as well. When all is said and done, we are all patients, and we are all members of the larger community. We all benefit from a healthy system, and we all suffer under a broken one. On the positive side, as individuals, our own Whole Health favorably influences the health of others in our community. Truly, as the Irish proverb puts it, “It is in the shelter of each other that people live.”

Putting It All Together: Personal Health Planning Using the Power of Community

During a Whole Health encounter, when Veterans focus on what matters most to them, the power of Community can become highly relevant. Consider how you might explore this with them—and for yourself—more fully. Often, it is simply changing the conversation in particular ways. Here are some examples of questions you could ask and suggestions you could make, when you are discussing Community in relation to someone’s MAP:

- How do you define Community? What community or communities do you identify as belonging to?

- How well are you integrated within your different communities?

- What potential opportunities do you have to connect more broadly? What barriers do you experience?

- Which community resources do you think you might benefit from tapping into? Would you be interested in learning about more options?

- Do you have particular knowledge, experience, skills, or interests that you could help others by sharing? How might you give back to your community or communities?

- What are some challenges faced by a community you belong to? How do you personally experience these challenges?

- Do you have the basic things you need, like clothing, heat, food, clean water, shelter?

- Tell me about the struggles in your life. How have they affected your health, or your family’s health?

- What would be important for me, as your clinician, to know about you, given that my background may be different than yours?

- What are some barriers to you achieving your health and well-being?

- Is there one small change you would like to make in your life? The self-care chapters in this Passport (Chapters 5-12) feature subtopics to consider, and all of them feature one called “Make One Small Change.” If it feels appropriate or empowering, is there something related to Community that you would like to make one small change?

As with all of the elements of Whole Health, these questions are also relevant for your own self-care—for care of the caregiver. Spending time with them can deepen your own Whole Health journey, too.

Wrapping Up

On that note, we have reached the conclusion this final chapter, and of our journey around the Circle of Health. Best wishes as you bring the various elements of the circle into your practice, and best wishes as you enhance your own personal Whole Health as well. May this Passport to Whole Health point you in new and valuable directions, so that you and the Veterans in your care can achieve things you previously did not think were possible! May you and all those you serve steadily move forward with all of your “MAPs” as you continue on your Whole Health Journey.

Special thanks to Codi Schale, PhD and Adrienne Hampton, MD for their significant contributions to the content of this chapter, as well as to Greg Serpa, PhD for guidance around mindful awareness research.